/cdn.vox-cdn.com/assets/1094488/aikens.png)

It's mid-March in Surprise, Arizona, just past morning sunrise, and Willie Mays Aikens sits in a folding chair, carpet beneath his feet, fluorescent lights above his head. His back is crouched, his eyes focused on a page filled with words in Spanish. Aikens is used to speaking in front of groups now, but he's about to address a room full of Kansas City Royals minor league Latin players. His former teammate and Hall of Fame third baseman, George Brett, will be arriving soon. But he is nervous. That stutter Aikens was born with, the stutter that caused so much ridicule growing up in Seneca, South Carolina, might resurface, in a second language no less.

"So happy I got this translated," he says.

"So happy I got this translated," he says.

Drugs are what brought Aikens a fluency in Spanish, but they also provided him 14 years of imprisonment, and a lifetime of not only pain but plenty of regret. Aikens' addiction to cocaine first landed him in jail when he played for the Royals and, he believes, eventually blackballed him from the sport. Mexico was the lone landing spot, the only circuit that would have him. So he played there for five years, during which he smoked crack nearly every day, slept with prostitutes, contracted hepatitis and fathered two girls.

"I was a tremendous junkie," he says. "When you are in a state of mind like that, you don't see yourself like that. You're in denial. You don't see that you have become selfish, and you only think about yourself."

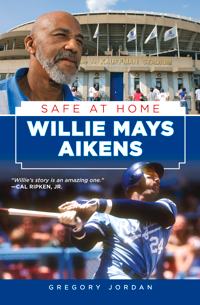

Today, though, he is not thinking about himself. He's thinking about this room full of players. He has a book coming out, called Safe At Home, a book by Gregory Jordan that is as honest and transparent an account of an athlete's life that has ever been written. Aikens, 57, has brought an advance copy of the book, and he plans on telling the players to read it. But first, he's going over his lines.

One of his daughters, Nicole, is Aikens' savior this morning. From her home in Mexico she shares with Aikens's wife, Sara, she emailed her father the translated speech. He wanted to make sure his grammar was proper and so here he is, studying his daughter's transcription, readying to deliver his testimony.

If anyone in baseball has a testimony to tell, it's Willie Mays Aikens.

What makes Aikens different than others who grew up poor, but whose excellence in athletics was a way out? Probably not much. But in Seneca, Aikens' large frame and massive talent were impossible to deny. He played football but he loved baseball. He loved sports in part because that meant less time spent at his home, a shack, he says, with no running water, no plumbing and where you could see the ground through the cracks in the floor.

"That's how poor we were," he says.

Aikens' mother, Cellie, was an unaffectionate woman who often worked the streets. He never met his father and his stepfather was a physically abusive alcoholic. He got to South Carolina State on a football scholarship, but his plan all along was to make the baseball team. He did, and the California Angels drafted him as their No. 1 pick in 1975. A lefthanded power hitter, Aikens could play first base, but he couldn't do anything else extraordinarily well, except hit. And he could hit. By 1979, he was in the big leagues to stay.

That was also the same year Aikens first tried cocaine. Walking down the hallway of his Minnesota hotel one night a few teammates called him into a room, where a pile of white powder greeted him.

He says he didn't think much of it, and it wasn't until the next season, this time playing in Kansas City after being traded in the offseason, that he used it again. It was that season, the season in which the Royals, behind future hall of famer Brett, future A.L. batting champion Willie Wilson and future inmate Aikens, would make the World Series, losing to the Phillies.

Aikens had an incredible postseason that year, culminating against the Phillies when he became the first player in major league baseball history with two multi-homer games in the same World Series. He also had the game-winning walkoff hit in Game 3, and overall hit .400, slugged 1.100 and had an OPS over 1.600, with four homers and eight RBIs in six games.

"He was a threat every time he got a bat in his hand," Brett says. "He wasn't freaked out, he didn't panic with two strikes, he didn't freak out or panic when a tough left-hander was on the mound."

That season was also the same one in which Aikens' cocaine use increased as the year progressed, and by the time the World Series arrived, he was regularly using it.

"Every day, every game of the World Series ... I snorted cocaine," he says. "It had become a part of my life."

Aikens saw no reason to stop. He was young, having fun, partying, at the top of his game.

"I hit two home runs in the first game of the World Series," he says. "I mean, I had a tremendous second half in 1980. We had just [whipped] the New York Yankees three games to zero. I had just drove in the winning run in the last game of the playoffs against the Yankees, against Ron Guidry, who had dominated me the whole year. And so there wasn't anything in my life at that particular time to say 'Willie, you shouldn't be doing this.' All of the evidence was there that was saying 'Willie, if you want to do this, go ahead and do it, because there is nothing wrong. You are playing well. Your life is great.' And so I did it, every game of the World Series."

He wasn't the only one on that team, and by 1983, he and three teammates, Wilson, Vida Blue and Jerry Martin had gotten entangled in an FBI drug investigation and they all copped pleas. What they didn't anticipate was that they would be made examples of; Aikens was sentenced to a year in jail and served 81 days for a misdemeanor cocaine possession charge. They became the first active players in the history of Major League Baseball to go to jail.

"It was frustrating for us, a lot of us, because they were good players," Brett says. "Willie Wilson was a great player. Willie Aikens was a great player. Jerry Martin, decent player. Vida Blue, former Cy Young award winner. So you take those guys out of our lineup and we weren't the same team."

For someone like Brett, who was one of the most intense, competitive players of his era, the loss of talent was deeply felt. Perhaps that was in part why Brett never responded to Aikens' letters from prison. Perhaps that's why he didn't reply to Aikens' desperate letter asking for help in petitioning the president for a pardon. And perhaps that's why Brett, since Aikens' release from prison in 2008, has done everything in his power to help his former teammate recapture his life.

By 1992 Aikens was back in Kansas City, smoking crack nearly every day, living as a hermit in his condo. Two years later, the KC police department sent an undercover agent and bought crack cocaine four times from Aikens. He was set up, and the quantity made it a felony and subject to mandatory minimum sentencing. The '80s crack epidemic created a hysteria, and the drug laws enacted placed penalties for crack possession and distribution 15 times higher than powder.

"They need to go," Aikens says about mandatory minimums. "They don't make any sense. They allow the police force and the FBI to become corrupt."

With crack being most pervasive in low-income, minority communities, many felt the laws were racially motivated. Aikens, who thinks race had something to do with the laws, was one of thousands of unfortunate recipients of that hysteria. He fought the charges, convinced he would not lose. He did. And when it came time to sentencing, the judge gave him 20 years and eight months.

George Brett has been one of Aikens' biggest allies since his former teammate was released from prison.

"I was devastated," he says.

Tracking time became impossible, his appeals all failed and his request for pardons -- in spite of the heroic, relentless efforts by his agent, Ron Shapiro, and others -- fell short. Cal Ripken Jr., a longtime client of Shapiro's, wrote letters, as did many others, but Brett, his former teammate, did not. He couldn't bring himself to wade into the politics.

"I felt guilty," Brett says. "But why me? Yeah I'm his friend, but [the politician] is going to listen to me?

"Thinking back on it, I probably wished I would have. It wasn't going to hurt, let's just say that. But I didn't do it."

Brett won't say it's the reason he was one of the first people who got in contact with Aikens when he was released in 2008 - after sentencing guidelines for crack cocaine convictions were relaxed - but clearly there was a need to reconnect with his old teammate, his old friend.

"When I found out he was in Kansas City, I didn't know where he was going to go, where he was going to live once he got out of prison," Brett says. "But when I found out he was in a halfway [house] in Kansas City, we communicated."

So one morning, by himself, George Brett, Hall of Fame third baseman, Kansas City legend, rolled up outside the halfway house in the city in which he became one of the best players of all time. He wasn't allowed in, so there he waited, idling in his car, for his ex-junkie, ex-con, ex-teammate.

Aikens emerged and the two rekindled their friendship. Brett took him to his son's high school, where Aikens - who credits his faith and spirituality for sustaining him, saving him and guiding him throughout the lowest moments of his incarceration - spoke to the students.

For 45 minutes, the man who stuttered his entire life spoke eloquently and without a trace of a speech impediment. Brett was floored, and within the next few years, Aikens would no longer working construction, but as a guest instructor for the Royals, reunited with the team, reunited with a uniform he once shamed.

Royals GM Dayton Moore gave Aikens his first baseball job after prison.

By last year, Aikens was hired by the Royals full time as a hitting instructor. He was officially back in baseball, based in Surprise, in charge of guiding some of the youngest members of the organization. Dayton Moore, the team's general manager, had taken the past few years to get to know Aikens, when Brett would bring him by the ballpark, and to other functions. He saw Aikens was a changed man, a man of faith. Moore brought him along slowly, first as a guest instructor, then as a full-time employee.

"We made it very clear to him that this is an opportunity for [him] to make a difference," Moore says. "This is not something that we're reaching out to you for the goodness of our heart because we're trying to give you a break. We're bringing you into this organization because we feel that you can make a difference in the lives of our young players and you can contribute. We're not in a position where we're just going to take you on just because we want to be good people."

Brett knew Aikens' presence would be a boon.

"He got mixed up at a very young age," Brett says. "He just got hooked up with the wrong people at the wrong time in his life and made some very bad decisions. It doesn't make [him] a bad person because he's corrected his decisions. And if he was still that same person he would have been in ''82, '83, '84, he would not be employed by the Kansas City Royals right now."

While there is nothing about the 14 years Aikens can do to ease the pain from the loneliness, despair and hopelessness he experienced, he says that had he not been arrested, he was destined for an early death. Prison afforded him the opportunity to be a parent, as well. His two daughters visited him from Mexico, and while he was a deadbeat dad for much of their childhood, he did provide them with as much money as he could, sending them to private schools. Sara was the mother of his second daughter, Nicole, and when Aikens was released in 2008, they reunited.

Not that it was easy, but they eventually married and at age 42, Sara became pregnant. Aikens, who says he's been sober for nearly 18 years, wanted to have a child that he could raise from the beginning, he wanted to right all the wrongs he had made as an absentee father. But Sara had lupus, and the pregnancy was a risk. In 2011, though, Sarita was born, and Sara emerged healthy.

Just a few weeks later, Aikens was in Surprise, on the third day of his job at a Royals fantasy camp when a team employee ran to him on the field, handing him the phone with the news that Sara had suffered a stroke. He had survived 14 years of prison, a few years of assilimating back into society but all it took was three days on the new job before Aikens' life was spun into turmoil.

The Royals encouraged him to return to Kansas City, where Sara was in a coma. She eventually emerged, but today half of her body is paralyzed and she cannot support herself or care for their child on her own. How could Aikens not have asked why me?

"Those thoughts do go through my head; not as much now as it did before," he says. "With my spiritual life now, I just can't say 'Well, why me with the bad things that happen in my life?' I have to say 'Why me?' with the good things that happened in my life, too."

"I've got to live my life one day at a time and do the things that are going to help raise my baby and support my wife as much as I can, and just live out the rest of my days, my life in this world being thankful, being grateful, for the life that I do have."

A few days before Aikens' address, Brett has the open floor. Each year, he gives a speech to the minor leaguers, but this year is different. This year, he tells them that his former teammate's speech is the one to absorb. Brett tells them he'll be in that room, listening to what Aikens says, and they would be foolish not to as well.

"I told them it's a very powerful message; he's no different than a lot of you guys are right here," Brett says, "a struggling minor leaguer trying to make it to the major leagues. And when he got to the major leagues, he made some bad choices.

"Pay attention to him. Learn something from him. He's a great man; give him the respect he deserves. When he's around you, give him the respect he deserves, just like I expect you to give all the coaches and the managers in the minor leagues the respect they deserve. I want you to give the same to Willie."

Thursday morning arrives and Aikens has successfully made it through his speech in Spanish. The second wave of players arrives, about 75 of them, sitting in a conference room behind center field at the Royals' big league spring training ballpark. Brett is there, so is former teammate Dennis Leonard, so is Willie Wilson, who is there as a alumni instructor, who also went to jail in 1983, just like Aikens.

The room silences and Aikens, holding papers in his hands, this time in his native language, adjusts his glasses, and opens with a joke. It's a hit - Aikens knows his crowd. And then he briefly goes into his spirituality before turning to Brett, who is sitting to Aikens' right, in a folding chair, just like everyone else.

Aikens thanks Brett for being one of the first to connect in 2008, thanks him for connecting him to Moore, and the Glass family and the baseball fraternity. He thanks him for being instrumental for having a job as a coach, for having a role in shaping others' lives. There is a pause, and 22 years after they first became teammates and went to the World Series, the Hall of Fame third baseman and his once-promising teammate give each other a look. Nothing more needed to be said.