Labrys portucalensis F11, a strain of aerobic bacterium from the Xanthobacteraceae family, can break down and transform at least three types of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), and some of the toxic byproducts, according to new research.

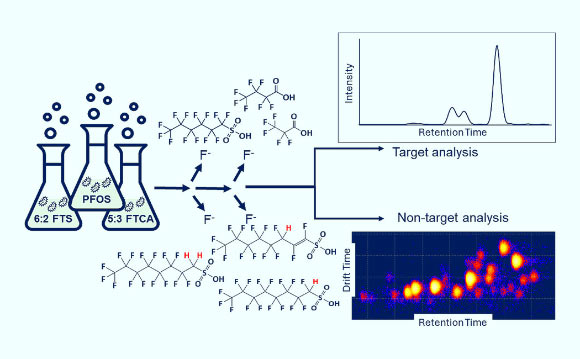

Labrys portucalensis F11 can be potentially used for PFAS biodegradation in contaminated environments. Image credit: Wijayahena et al., doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.178348.

“The bond between carbon and fluorine atoms in PFAS is very strong, so most microbes cannot use it as an energy source,” said Professor Diana Aga, a researcher at the University at Buffalo and SUNY.

“The Labrys portucalensis F11 bacterial strain developed the ability to chop away the fluorine and eat the carbon.”

Labrys portucalensis F11 was isolated from the soil of a contaminated industrial site in Portugal and had previously demonstrated the ability to strip fluorine from pharmaceutical contaminants. However, it had never been tested on PFAS.

In the new study, Professor Aga and her colleagues found that Labrys portucalensis F11 metabolized over 90% of perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) following an exposure period of 100 days.

PFOS is one of the most frequently detected and persistent types of PFAS and was designated hazardous by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency last year.

Labrys portucalensis F11 also broke down a substantial portion of two additional types of PFAS after 100 days: 58% of 5:3 fluorotelomer carboxylic acid and 21% of 6:2 fluorotelomer sulfonate.

Unlike many prior studies on PFAS-degrading bacteria, the new study accounted for shorter-chain breakdown products — or metabolites.

In some cases, Labrys portucalensis F11 even removed fluorine from these metabolites or broke them down to minute, undetectable levels.

“Many previous studies have only reported the degradation of PFAS, but not the formation of metabolites,” said Mindula Wijayahena, a Ph.D. student at the University at Buffalo and SUNY.

“We not only accounted for PFAS byproducts but found some of them continued to be further degraded by the bacteria.”

PFAS are a group of ubiquitous chemicals widely used since the 1950s in everything from nonstick pans to fire-fighting materials.

They’re far from the meal of choice for any bacterium, but some that live in contaminated soil have mutated to break down organic contaminants like PFAS so that they can use their carbon as an energy source.

“If bacteria survive in a harsh, polluted environment, it’s probably because they have adapted to use surrounding chemical pollutants as a food source so they don’t starve,” Professor Aga said.

“Through evolution, some bacteria can develop effective mechanisms to use chemical contaminants to help them grow.”

The findings were published in the journal Science of The Total Environment.

_____

Mindula K. Wijayahena et al. 2025. PFAS biodegradation by Labrys portucalensis F11: Evidence of chain shortening and identification of metabolites of PFOS, 6:2 FTS, and 5:3 FTCA. Science of The Total Environment 959: 178348; doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.178348