French Grammar book 3

- 2. THE 2

- 3. ESSENTIAL FRENCH BOOK All you need to learn French in no time Bruce Sallee and David Hebert Avon, Massachusetts 3

- 4. Contents Introduction Pronouncing and Writing French The Alphabet Sounds Liaison, Elision, and Enchaînement Capitalization Punctuation Marks Accents and Diacritical Marks Using Everyday Expressions Colloquial, Idiomatic, and Other Useful Expressions Salutations and Greetings Numbers and Dates Developing a Basic Vocabulary Conjunctions Basic Words to Memorize Describing Things and People Understanding Articles Discovering French Articles The Definite Article The Indefinite Article The Partitive Article Using Nouns Understanding Nouns Gender of Nouns Plural Nouns Forming Present-Tense Verbs Verb Forms: The Infinitive Conjugating Verbs in the Present Tense Idiomatic Expressions with Avoir The Present Participle Asking Questions and Giving Orders Asking Basic Questions Asking Questions with Interrogative Pronouns 4

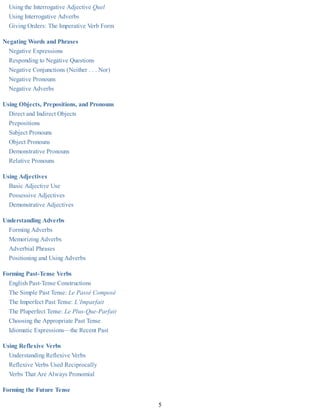

- 5. Using the Interrogative Adjective Quel Using Interrogative Adverbs Giving Orders: The Imperative Verb Form Negating Words and Phrases Negative Expressions Responding to Negative Questions Negative Conjunctions (Neither . . . Nor) Negative Pronouns Negative Adverbs Using Objects, Prepositions, and Pronouns Direct and Indirect Objects Prepositions Subject Pronouns Object Pronouns Demonstrative Pronouns Relative Pronouns Using Adjectives Basic Adjective Use Possessive Adjectives Demonstrative Adjectives Understanding Adverbs Forming Adverbs Memorizing Adverbs Adverbial Phrases Positioning and Using Adverbs Forming Past-Tense Verbs English Past-Tense Constructions The Simple Past Tense: Le Passé Composé The Imperfect Past Tense: L’Imparfait The Pluperfect Tense: Le Plus-Que-Parfait Choosing the Appropriate Past Tense Idiomatic Expressions—the Recent Past Using Reflexive Verbs Understanding Reflexive Verbs Reflexive Verbs Used Reciprocally Verbs That Are Always Pronomial Forming the Future Tense 5

- 6. English Future-Tense Constructions The Future Tense in French Forming the Conditional Tense Uses of the Conditional Tense Using the Conditional Tense to Be Polite The Past Conditional Tense Forming the Conditional Tense Forming the Past Conditional Tense The Verb Devoir in the Conditional Tense Understanding the Subjunctive Mood Understanding the French Subjunctive Forming the Subjunctive Mood Specific Uses of the Subjunctive The Past Subjunctive Traveling in French-Speaking Countries Modes of Transportation Travel Destinations Money In a Restaurant Beverages Shopping Terms Stores, Shops, and Markets Movies Books, Newspapers, and Magazines TV , Radio, and the Internet Studying and Working in French-Speaking Countries School Terms Technology The Working World Family, Friends, and Y ou Family Holidays and Occasions Friends Pets Parts of the Body Clothing Colors 6

- 7. Y our House or Apartment Your Daily Routine A Tour of Your Home Rooms in a House Apartments In the Kitchen and at the Market Your Grocery List Appendix: French-to-English Dictionary Copyright 7

- 8. Introduction French is a part of the language family known as Romance languages, so called because they came from Latin (which was spoken by Romans—get it?). Included in this family are Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, and Romanian; these languages share many similarities, because they all come from a common source. Despite the similarities, however, each are distinct and different, and many agree that French is one of the most “romantic” languages of all, even if they are referring to romance in a different sense. French, naturally, originated in France, but you can now find it spoken around the world. In North America, you may run across French speakers in Canada or Louisiana. It is widely spoken in Europe and Africa, and even some Asian countries use French as a major language. In short, you’ll never know where it may come in handy to know a little bit of French. In this book, we concentrate on standard French, which is sometimes referred to as Parisian French. As the term “standard” implies, it should be understood wherever you find yourself, even if you have a bit of trouble understanding what other people are saying. In a sense, the French language has its own governing body. The French Academy, or l’Académie française, was originally established in 1635 and oversees the development of the language. It registers all official French words; until the Academy approves it, a word isn’t technically a part of the language. Despite their efforts to preserve the French language, some expressions still slip in: You’ll inevitably be understood if you order un hamburger or un hot-dog in French, even if the Academy doesn’t acknowledge these words. 8

- 9. CHAPTER 1 Pronouncing and Writing French This chapter lets you dive into French, with a little speaking and a little writing. Here, you discover how to pronounce basic French letters, letter combinations, and words. You begin writing by focusing on punctuation marks and accents. You’ll be pronouncing and writing like a French pro in no time! 9

- 10. The Alphabet While French and English use the same alphabet, in French, the letters are pronounced a little differently. If you ever have to spell your name out at a hotel, for example, you want to make sure that you’re understood. Table 1-1 THE FRENCH ALPHABET Letter Sound Letter Sound a ahh n ehnn b bay o ohh c say p pay d day q koo e ehh r aihr f eff s ess g jhay t tay h ahsh u ooh i ee v vay j jhee w doo-bluh-vay k kahh x eex l ehll y ee-grek m ehmm z zed Keep the following points in mind when pronouncing letters in French: The sound of the letter “e” in French is very similar to the beginning of the pronunciation of the English word “earl.” The letter “g” is pronounced jhay, with a soft “j” sound, like in “Asia.” The pronunciation of the letter “j” uses the same soft “j,” but with an “ee” sound at the end. The letter “n,” especially when appearing at the end of words, is pronounced very softly, with a nasal quality. “Q” in English has a distinct “ooh” sound in it; it is pronounced similarly in French, but without the “y” sound. When two letter “l”s appear together, it creates a “yeh” sound. The letters are not pronounced the same as one letter; it sounds like the beginning of the English word “yearn.” The French “r” is more guttural than the English one, made at the back of the throat instead of at the front. 10

- 11. Sounds Most of the consonants in French are pronounced the same as in English, but many of the vowel sounds differ. It is almost impossible to describe the true sound of French using text. For best results, try to listen to actual French being spoken; only then can you appreciate the sound of the language. The following, however, is a list of sounds used in the French language. Practice making the sounds a few times, and say the example words out loud. on: Sounds much like “oh” in English, with just a hint of a soft “n” at the end. You will find it in words such as maison (meh-zohn, meaning “house”) and garçon (gar-sohn, meaning “boy”). ou: An “ooh” sound that you’ll encounter in words such as tout (tooh, meaning “all”). oi: A “wha” sound, much like the beginning of the English word “waddle.” A French example is soir (swahr, meaning “evening”). oin: Sounds much like the beginning of “when” in English, with only a hint of the “n” coming through, very softly. Coin (kwheh, meaning “corner”) and moins (mwheh, meaning “less”) are examples. ai: Sounds like “ehh.” You’ll find it in a great many words, including maison and vrai (vreh, meaning “true”). en: Sounds similar to “on” in English, but with a much softer “n” sound. You’ll find it in words like encore (ahnk-ohr, meaning “again”) and parent (pahr-ahn, meaning “parent”). an: Is pronounced the same way as en. eu: To make this sound, hold your mouth like you’re going to make an “eee” sound, but say “oooh” instead; it sounds much like the beginning of the English word “earl.” Heure (ehhr, meaning “hour”) is an example. in: Pronounced like the beginning of the English word “enter,” but again with a much softer “n” sound. Magasin (may- guh-zehn, meaning “store”) and pain (pehn, meaning “bread”) are examples. er: Sounds like “ayy.” You will find this at the end of many verbs, such as parler (parl-ay, meaning “to speak”) and entrer (ahn-tray, meaning “to enter”). Sometimes, letters are silent and are not pronounced; this often occurs with letters at the end of words. The letters are still required in written French, of course, but you don’t hear them. Here are the letters to watch: Words ending in -d: chaud (show), meaning “hot.” Words starting with h-: heureux (er-rooh), meaning “happy.” Words ending in -s: compris (com-pree), meaning “included.” Words ending in -t: achat (ah-sha), meaning “purchase.” Words ending in -x: choix (shwa), meaning “choice.” In French, the letter “h” is usually silent; words that begin with it are usually pronounced as if the “h” wasn’t there at all. In French, a silent letter is known as muet (moo-eh), and the silent “h” as h muet (ahsh moo-eh). There are a few cases where the “h” will be pronounced; it is then known as an aspirated h, or h aspiré (ahsh as-pee-ray). The majority of French words that begin with “h” are pronounced with an h muet, so, when pronounced, they’ll sound as if they begin with a vowel. Words that begin with an h aspiré are the exception. Often, in spoken French, words are run together. This occurs when using words that begin with vowels after words that end in a hard consonant sound. When learning the language, this can cause consternation for new speakers, as it can be difficult to understand what other people are saying. In addition, words can be shortened, and contractions can be formed, adding to the confusion. Other times, the syllables are just pushed together, so two or three words can sound like one long word instead. 11

- 12. French is known for the rolling “r” sound. You can learn to roll your r’s, too, with just a little bit of practice. Start to make a “k” sound and hold it. Close your throat a little bit, breathe out slowly, and start to say “raw.” Don’t worry if it starts to come out as “graw”—keep doing it. Practice this a couple of times a day, and you’ll soon sound just like Maurice Chevalier. In French, this is known as enchaînement, or linking the sounds together. Not all linked sounds are due to enchaînement, however. Liaison and elision are grammatical concepts that also result in sounds getting pushed together (see the following section). Don’t be afraid to try speaking French: French speakers are usually very patient when speaking with people who are new to the language. As a rule, native French speakers are pleased that someone is taking the time to try to communicate using their language, and they’re usually happy and eager to help you understand. This is a European approach, quite different from North American expectations, which assume that everyone should speak English—and speak it well. You’ll find the French to be very accommodating with your budding linguistic abilities; don’t be afraid to express yourself. 12

- 13. Liaison, Elision, and Enchaînement Some pronunciation areas are governed by the grammatical concepts elision and liaison, and enchaînement also affects pronunciation of certain words. Keep the following pronunciation points in mind. Liaison Liaison occurs when one word ends in a consonant and the following word begins with a vowel. It is only a concern in spoken French, of course, but it is still a part of the formal language rules. Its proper usage must be observed at all times. Using Liaison with Nouns Whenever an article or number that ends in a consonant is used with a noun that begins with a vowel, the final letter joins with the next vowel sound. Table 1-2 LIAISON WITH NOUNS FRENCH PRONUNCIATION ENGLISH un enfant uhn-nahn-fahn child les abricots lay-zab-ree-ko apricots deux hommes doo-zom two men Using Liaison with Verbs When a pronoun that ends in a consonant is used with a verb that begins with a vowel, liaison occurs. Nous avons, for example, which means “we have,” is pronounced noo-za-vohn. Ils ont, which means “they have,” is pronounced eel-zohn. Using Liaison with Verbs in Sentences Using Inversion When a verb that ends in a consonant is used in a question constructed with inversion (see Chapter 7), and the subject pronoun starts with a vowel, liaison occurs. Ont-elles?, for example, which means “Have they?” is pronounced ohn-tell. Using Liaison with Certain Adverbs, Conjunctions, Prepositions, and Other Expressions Certain adverbs, conjunctions, prepositions, and other expressions use liaison. Here are some examples: Chez-lui (shay-loo-ee) Comment allez-vous? (commahn-tallay-voo) Vingt et un (vehn-tay-uhn) Knowing When Liaison Must Not Be Used 13

- 14. There are some times when liaison must not be used under any circumstances, even though it may appear that liaison is appropriate or even expected. The use of liaison in these situations may cause comprehension problems, because native speakers definitely won’t be expecting it. The resulting phrase may sound like some other phrase, causing your listeners to wonder what on earth you’re talking about. After a noun used in the singular: For example, l’étudiant a un livre (lay-tchoo-dee-ahn ah uhn leevr). After et, the word for “and”: For example, vingt et un (vehn-tay uhn).(Note: the liason between vingt and et is correct; there is no liason between et and un.) In front of an h aspiré: For example, des héros (day ay-ro). Elision Elision occurs when two vowels appear together—one at the end of a word, and the other at the beginning of the word immediately following it. One of the vowels is dropped, and the remaining letter is joined to the following word with an apostrophe. l’eau, pronounced low, is an elision of la + eau (water) l’été, pronounced lay-tay, is an elision of le + été (summer) Elision is a frequent occurrence with articles and nouns, but can also occur with verbs and subject pronouns, and even prepositions (see Chapter 9). This affects both written and spoken French, so it is an important concept to remember. When does elision, or dropping a vowel, occur? Elision can occur with any of the following words when followed by another word that begins with a vowel: ce, de, je, la, le, me, ne, que, se, si, and te. Enchaînement Enchaînement, unlike liaison and elision, is a matter of pronunciation only; it does not affect written French. It does, however, operate in a similar fashion, pushing the sounds of words together. Instead of being governed by vowels and consonants, though, enchaînement is governed by phonetic sounds. And instead of affecting the last letter of a word, enchaînement affects the last sound. il a (ee-la) une école (ooh-nay-kohl) elle est (el-lay) 14

- 15. Capitalization For the most part, French follows the same rules regarding capitalization as English, with a few exceptions. In French, a capital letter is known as a majuscule. Capitalized words are said to be en majuscules. The following shows the types of words that are capitalized in French: The first word in a sentence is capitalized. Both first and last names are capitalized. Names of cities, countries, and continents are capitalized. Directions are capitalized to indicate a specific place, like l’Amérique du Nord (f) (North America). When used to indicate a general direction, like le nord (north), no majuscule is used. When a word is used as a noun to indicate the nationality of a person, for example, un Français (a Frenchman), the word is capitalized. 15

- 16. Punctuation Marks Written French looks very similar to English, so reading books in French should seem almost familiar. For the most part, French uses the same punctuation marks, and they function in much the same way as in English. Included in this section are the French terms for many punctuation marks; they are handy words to know, and you never can tell when you may be called upon to use them. Brackets Brackets, called les crochets (lay crow-shay), are often used to show words inserted into quoted text to help explain the original. In English, they are sometimes referred to as “square brackets.” They function the same in both languages. Colon The colon, called les deux-points (lay doo-pwehn), is used to introduce another phrase that is related to the previous one. Usually, the following phrase will be an elaboration on a point or something that explains the sentence more clearly. The colon functions the same in both languages. Comma The comma, called la virgule (la vehr-gool), is used in the same way as English uses them, but remember that French also uses une virgule when indicating an amount of money. For example, 1.25 in English would be 1,25 in French, exchange rates notwithstanding. Exclamation Point An exclamation point, called le point d’exclamation (le pwehn dex-kla-mass-yohn), can be used at the end of a sentence to indicate an element of surprise, excitement, or other intense emotion. The usage between French and English is, for the most part, interchangeable. Ellipsis An ellipsis, a series of three periods that’s called les points de suspension (lay pwehn de soos-pehnss-yohn) in French, is often used to indicate sections of quoted text that have been omitted for whatever reason. In dialogue, it can also be used to indicate trailing speech. A way to remember the French term is to think that something is left unsaid when the marks are used, creating an aura of suspense. Parentheses Parentheses, called les parenthèses (lay pahr-ent-ez), are used in the same way as in English, usually to refer to an aside statement without interrupting the flow of the sentence. Wrapping a phrase in parentheses indicates that the phrase is meant to 16

- 17. elaborate but at the same time be self-sustaining, separate from the phrase that appears around it. Period The period, called le point (le pwehn), is used at the end of a sentence; anytime you use a period in English, you can do the same in French, except when indicating amounts of money. Question Mark A question mark, called le point d’interrogation (le pwehn dint-hehr-oh-gass-yohn), is used to indicate a question. In written French, you will most often see est-ce que used to indicate a sentence; in dialogue, however, you may encounter inversion or even plain sentences that use a question mark (see Chapter 7). In the latter case, the dialogue is intended to be read with intonation; the question mark is your clue. Quotation Marks French quotation marks, called les guillemets (lay gee-meht), appear slightly different from English ones. Instead of using symbols that look like apostrophes, as in English, French uses small double arrows that wrap around the quotation, as follows: Il dit: «je ne sais pas.» He said, “I don’t know.” Semicolon A semicolon, called le point-virgule (le pwehn-vehr-gool), is used to attach a phrase that is loosely related to the previous phrase in the sentence. Like the comma and period, its usage is primarily interchangeable with the English usage. 17

- 18. Accents and Diacritical Marks In order to provide guides to pronunciation, French uses accents and diacritical marks, which are pronunciation marks that appear with some letters. There are three accents commonly used with vowels; the grave, the aigu, and the circonflexe. The Aigu Accent The aigu (ay-gooh) points upward and toward the right, as in é. In English, it is known as the acute accent. Although it only appears over the letter “e,” it can become an integral part of a word, substantially changing its meaning. The aigu accent also provides important clues about where the word fits in a sentence. Whenever it appears, it changes the pronunciation of the “e” from an “ehh” sound (like the middle “e” sounds in “treble”) to an “ay” sound. réveil (ray-vay): alarm clock médecin (may-dehh-sehn): doctor épicé (ay-pee-say): spicy The Grave Accent The grave accent (pronounced like the beginning “grav” in “gravel”) falls to the left, as in è. The grave accent can appear over the letter a, e, i, o, or u; however, it changes the pronunciation only when it appears above e. It’s not so important in spoken French, so it can be easy to forget about. The grave accent must be used in written French, however, so pay close attention to the words that use it. très (treh): very où (ooh): where troisième (twa-zee-emm): third The Circonflexe The circonflexe (sir-kohn-flex) accent appears over vowels, like a little hat over the letter, as in ô. It doesn’t modify the pronunciation at all, but the French Academy has opted to keep it, so it remains with the language. forêt (fohh-ray): forest hôtel (owe-tel): hotel hôpital (owe-pee-tal): hospital The Cédille The cédille (say-dee)—in English, the cedilla, pronounced se-dill-ah—is a diacritical mark appearing underneath the letter “c” that makes look like it has a tail: ç. It indicates a soft “s” sound instead of the hard “k” sound the letter “c” would normally have if it appeared before the vowels “a,” “o,” or “u.” For example, the French language is referred to as français— 18

- 19. pronounced frahn-say. The “c” becomes soft, turning into an “s.” (If the cedilla were not present, the word would be pronounced frahn-kay.) garçon (gahr-sohn): boy leçon (leh-sohn): lesson façon (fass-ohn): manner The Tréma The tréma (tray-ma) is the French word for the two dots that appear above the second vowel when two vowels are situated together. In English, it is known as an umlaut, and is used in some foreign words, including words borrowed from French. The diacritical mark tells you that the second vowel is to be pronounced on its own, distinct from the vowel preceding it. Noël and naïve are examples of French words that are commonly used in English; Noël is pronounced no-well, and naïve is pronounced nigh-eve; in French, the sound is softer and pronounced more to the front of the mouth. coïncidence (ko-ehn-see-dahnss): coincidence Jamaïque (jam-eh-eek): Jamaica Noël (no-ell): Christmas 19

- 20. CHAPTER 2 Using Everyday Expressions This chapter gets you ready to speak French like a native! Here, you’ll discover a wide range of expressions that don’t necessarily make sense when you translate them word for word, but make a whole lot of sense to the French speaker you’re communicating with. To aid in that communication, this chapter also helps you understand greetings and basic numbers. 20

- 21. Colloquial, Idiomatic, and Other Useful Expressions Almost all languages have some peculiarities that defy literal translation. English is rife with expressions that cannot be taken literally. Consider the phrase: How is it going? How is what going? Wouldn’t it be much easier simply to say, “How are you?” These types of phrases often cause problems for a new language student, no matter which language. You can probably think of other examples that would be difficult to translate into another language. These nonliteral phrases are known as idiomatic expressions, which simply means that the expression is unique to that language. Whenever you come across idiomatic expressions, you cannot translate them literally. You must go to the heart of the phrase and instead translate its sentiment so that the proper meaning is conveyed. Idiomatic expressions usually follow a certain pattern of construction, and they are very much a part of the grammar of each language. Closely related to idiomatic expressions are colloquial expressions. Often, colloquial expressions are also unique to the language, but the meaning of the term is slightly different. Colloquial expressions usually bend the rules of grammar a little bit, but are so widely recognized within the spoken language that it’s acceptable to use them in everyday speech. Some expressions are widely understood by native speakers of a language, but attempts at literal translation will only confuse others. When learning a new language, in addition to memorizing the words and grammar, you also have to remember some unique expressions that only work in that particular language. To remember the difference, idiomatic expressions are idiosyncratic to the language; they are unique to the language, and are also a part of the official rules. Colloquial expressions, however, are not part of the official language; despite this, they are still widely used. Colloquial expressions can take time to work their way into dictionaries, so don’t be afraid to ask someone what something means when you don’t understand. This section shows the French language in action, with complete explanations. You’ll learn how each phrase is constructed and what each word means, but don’t worry about memorizing the explanations. Feel free to memorize the phrases, however, because you’ll be happy to know them wherever you are in the French-speaking world. Don’t expect to understand everything right away. As you learn more of the language, you’ll be able to use these sentences as a point of reference, exchanging words for others to make your own sentences. French will seem easy. It’s simply a matter of substituting the right word. Comment allez-vous? Pronounced commahn-tallay-voo, this phrase means, “How are you?” Comment means “how.” It is often used to begin questions in French. Allez is a verb that means “to go”; vous is a subject pronoun meaning “you.” Literally, the phrase means “How are you going?” As an idiomatic expression, however, it is basically equivalent to “How are you?” or “How is it going?” in English. Normally, the subject pronoun vous appears before the verb, but this sentence uses inversion to form a question. When inversion is used, the verb and subject pronoun switch positions; you can find out more about inversion in Chapter 7. Because this is a question, when pronouncing this phrase, your voice should raise slightly on the final vous sound, the same way your voice rises when asking, “How are you?” in English. This is known as intonation. 21

- 22. Notice that the “t” sound at the end of comment, when pronounced, is attached to the beginning of allez, making it sound like “tallay.” This is an example of enchaînement, the French name for stringing the sounds together (see Chapter 1). Comment vous appelez-vous? Pronounced commahn voo-zap-lay-voo, this phrase means, “What is your name?” Literally, this expression means “How do you call yourself?” Appelez means “call”; you’ll notice that vous, however, appears twice. It’s a versatile word that can pull double duty. The last vous is the subject pronoun, and means “you.” The first vous, however, is used as a reflexive pronoun, and means “yourself.” Jump to Chapter 13 to find out more about reflexive pronouns. Je ne parle pas français. Pronounced jhun-parl pah frahn-say, this phrase means, “I don’t speak French.” Using this phrase, you can let someone know that you don’t speak French; often, the person will try to get by in another language or help you find someone who speaks English. You can even use it in combination with the next phrase. Je is the French word for “I.” You use it whenever you are talking about yourself individually. It only appears as the subject of the sentence. Ne and pas are the French equivalent to “not”; they always appear together in written form, but the ne is sometimes dropped in conversational French. The ne is just a language pointer to let you know that the subject is going to be in the negative, while pas means “not.” There are other negative expressions in French, but ne … pas is by far the most common you’ll encounter. Français, as you may have guessed, means French. Parlez-vous anglais? Pronounced parlay voo ahng-lay, this phrase means “Do you speak English?” This is a polite way of asking if another person knows English; it can also be used to address more than one person. Parlez is the verb, meaning “speak.” Vous means “you” (in this instance, a plural term), and anglais is the French term for English. Note that there’s no enchaînement between vous and anglais; because this is a question that inverts the subject and verb, the “s” sound in vous does not get carried to the beginning of anglais. Of course, if you slip up and accidentally tie them together, people should still understand you; be prepared, however, for a correction before receiving the answer. Je m’appelle Frank. Pronounced jhe ma-pell Frank, this phrase means “My name is Frank.” This one will work only if your name is Frank, but feel free to use your own name and give it a try. It’s the colloquial French way of saying your name; its literal interpretation takes a more circuitous route, translating as “I call myself Frank.” 22

- 23. Remember that with colloquial and idiomatic expressions, literal translations don’t work. Je m’appelle is one of them. As you encounter these expressions, you’ll get to understand the idiosyncrasies and be able to recognize when a literal translation isn’t appropriate. Before you know it, you’ll recognize these phrases and will be able to speak French like a natural. Je is the subject, meaning “I,” and appelle is the verb, meaning “call.” Me is a reflexive pronoun; it works with the verb to show that it’s an action that goes back to the subject, just like “himself” or “myself” in English. You’ll find out more about reflexive pronouns in Chapter 13. Où est la salle de bain? Pronounced ooh ay la sell de behn, this term means “Where is the washroom?” Où means “where,” and est means “is.” La salle de bain, if you were to translate it literally, means “the room of bath,” with salle meaning “room” and bain meaning “bath.” Sometimes, words carry a unique connotation in a language that doesn’t exist in another language. An example of this is the English word “toilet”—it’s hardly acceptable for most polite conversations. However, in French, it’s completely acceptable to ask: Où est la toilette? (ooh ay la twa-lett), which means “Where is the toilet?” When you think about it, it makes sense; in most situations, you’re not asking for a room with a bath in it. You’re looking for something else entirely. In French, they get right to the point, so don’t feel bashful asking for the toilet. In fact, sometimes if you ask, “Où est la salle de bain?,” you may even receive the response, “La toilette?” Simply say oui (pronounced like whee, means “yes”) and follow the directions; you can reflect on the differences between French and English while you’re otherwise occupied. Je ne comprends pas. Pronounced je ne com-prahn pah, this phrase means “I don’t understand.” Because you’ve just learned about je and ne … pas, you should have a fairly easy time translating this one. Comprends means “understand”—you’ll notice that it’s very similar to the English word “comprehend.” This phrase works only for you as an individual, though. If you were with another person and referring to the two of you, you would say it slightly differently: Nous ne comprenons pas (noo ne com-prin-own pah), which means “We do not understand.” Nous is the French word for “we”; it is another subject pronoun. Comprenons is the same verb, with a different ending to match nous. In French, the verb endings change to reflect the subject of the sentence, just like some words do in English, even if only slightly, such as “I understand” versus “he understands.” French speakers worldwide will recognize this statement. They will either repeat the question or will try to state things a different way. If you find yourself stuck, the following statements can also help get you out of just about any situation. Répétez, s’il vous plaît. 23

- 24. Pronounced rep-a-tay seel voo play, this phrase means “Please repeat.” S’il vous plaît is the French way of saying “please.” Literally translated, it means “if it pleases you.” Répétez is the verb, meaning “repeat”; because it doesn’t have the word vous with it, though, it’s an instruction. In linguistic circles, that’s known as an imperative; you’ll discover more about that verb form in Chapter 7. In a sense, it’s an order to repeat; the s’il vous plaît softens it into a very polite way to ask someone to repeat something. Plus lent, s’il vous plaît. Pronounced ploo lahn, seel voo play, this phrase means “slower, please.” Literally it means “more slow, please” but in French, this is an acceptable way to ask someone to slow down while speaking so that you can understand. French is an expressive language, and sometimes its speakers tend to move pretty fast; if you find that the person with whom you’re conversing is speaking too fast for you to comprehend, simply say this phrase. Plus lent is a valuable phrase to know, but use it wisely—it’s like a secret formula. People will slow down to accommodate you. Use it too often, however, and you may find people growing impatient with you. You can also use plus lent in conjunction with both je ne comprends pas and répétez, s’il vous plaît. For example, faced with someone you don’t quite understand, you could say: Je ne comprends pas. Répétez, s’il vous plaît, plus lent? Now, the person knows that you don’t understand, and you have asked nicely if he or she would repeat it a little more slowly. 24

- 25. Salutations and Greetings The following vocabulary list includes words and expressions that you can use as simple greetings or responses to address friends and family. Memorize these expressions; they are relatively easy to remember, and they go a long way toward making you sound like a natural. Table 2-1 SALUTATIONS AND GREETINGS FRENCH PRONUNCIATION ENGLISH à bientôt ah bee-ehn-toe see you soon à demain ah deh-mehn see you tomorrow à toute à l’heure ah toot ah luhr see you later à vos souhaits ah vo soo-eht bless you (after someone sneezes) adieu ah-dyuh farewell au revoir oh rhe-vwahr goodbye bienvenue bee-ehn-veh-noo welcome bonne chance! buhnn shahnce good luck! bonne nuit buhnn nwee good night, sleep well bonjour bohn-jhoor hello, good morning, good afternoon bonsoir bohn-swahr good evening bravo brah-vo well done de rien de ree-en you’re welcome enchanté ahn-shahn-tay pleased to meet you (male speaker) enchantée ahn-shahn-tay pleased to meet you (female speaker) merci mehr-see thank you merci beaucoup mehr-see bo-koo thank you very much salut sah-loo Hi! Bye! santé sahn-tay Cheers! tant pis tahn pee too bad, nevermind 25

- 26. Numbers and Dates In addition to using the same alphabet (see Chapter 1), French also uses the same numerical symbols. In English, these are known as Arabic numbers; in French, they are called chiffres arabes. Math, at least, looks the same in French. When the numbers are pronounced, however, there are striking differences. The bad news is that you’ll need to do a little bit of memorization work to become familiar with the numbers, as you’ll have to learn new names for them. Fortunately, there aren’t very many of them; they get combined to form larger numbers, just like English does with “thirty-seven” and “seventy-two.” Unfortunately, the French rules are a little bit different, so you may also have to spend some time memorizing the way larger numbers are constructed. You may want to visit this section periodically to brush up. There are actually two kinds of names for numbers. There are cardinal numbers, which are the regular numbers “one,” “two,” three,” and so on. But there are also ordinal numbers, which define the relationship of the number to others, such as “first,” “second,” and “third.” Cardinal Numbers Numbers from zero to nineteen are fairly straightforward: Table 2-2 NUMBERS FROM ZERO TO NINETEEN FRENCH PRONUNCIATION ENGLISH zéro zay-ro zero un(e) uhn/oon one deux duh two trois twah three quatre kat-ruh four cinq sank five six sees six sept set seven huit wheat eight neuf nuf nine dix dees ten onze ohnz eleven douze dooze twelve treize trayze thirteen quatorze ka-torz fourteen quinze kayhnz fifteen seize sayze sixteen dix-sept dees-set seventeen dix-huit dee-zweet eighteen dix-neuf dees-noof nineteen The numbers twenty through sixty-nine follow a consistent pattern, very similar to the English way of naming a group of tens —like “twenty”—and following it with another word, such as “one,” to form “twenty-one.” In written French, the numbers are 26

- 27. combined with a hyphen, with the exception of et un, which contains two words and translates as “and one.” Table 2-3 NUMBERS FROM TWENTYTO TWENTY-NINE FRENCH PRONUNCIATION ENGLISH vingt vehn twenty vingt et un vehn-tay-uhn twenty-one vingt-deux vehn-doo twenty-two vingt-trois vehn-twah twenty-three vingt-quatre vehn-kat-ruh twenty-four vingt-cinq vehn-sank twenty-five vingt-six vehn-sees twenty-six vingt-sept vehn-set twenty-seven vingt-huit vehn-wheat twenty-eight vingt-neuf vehn-noof twenty-nine To form numbers between thirty and sixty-nine, simply add the appropriate number after the end of the word for the group of tens. Table 2-4 NUMBERS FROM THIRTYTO SIXTY-NINE FRENCH PRONUNCIATION ENGLISH trente trahnt thirty trente et un trahnt-ay-uhn thirty-one trente-deux trahnt-doo thirty-two quarante karant forty quarante et un karant-ay-oon forty-one quarante-deux karant-doo forty-two cinquante sank-ahnt fifty cinquante-quatre sank-ahnt-katr fifty-four soixante swahz-ahnt sixty soixante-neuf swahz-ahnt-noof sixty-nine At seventy, a new pattern emerges. Instead of having a separate word for “seventy,” “sixty” and “ten” are combined to form soixante-dix. The numbers eleven through nineteen are used to designate numbers up to seventy-nine. Eighty doesn’t have a separate word, either. Instead, it is designated as quatre-vingt—in other words, four twenties, which does indeed add up to eighty. Note that in written French, eighty-one becomes quatre-vingt-un, and does not use the et found in the earlier numbers. Ninety is very similar to seventy, combining the quatre-vingt of “eighty” with dix to form quatre-vingt-dix. The numbers then follow the same progression, up to ninety-nine. Table 2-5 NUMBERS FROM SEVENTYTO NINETY-NINE 27

- 28. FRENCH PRONUNCIATION ENGLISH soixante-dix swahz-ahnt-dees seventy soixante et onze swahz-ahnt ay ohnz seventy-one soixante-douze swahz-ahnt-dooz seventy-two quatre-vingt katr-vehn eighty quatre-vingt-un katr-vehn-un eighty-one quatre-vingt-deux katr-vehn-doo eighty-two quatre-vingt-dix katr-vehn-dees ninety quatre-vingt-onze katr-vehn-ohnz ninety-one quatre-vingt-douze katr-vehn-dooz ninety-two quatre-vingt-treize katr-vehn-trayz ninety-three quatre-vingt-quatorze katr-vehn-katorz ninety-four quatre-vingt-quinze katr-vehn-kaynz ninety-five quatre-vingt-seize katr-vehn-sayze ninety-six quatre-vingt-dix-sept katr-vehn-dees-set ninety-seven quatre-vingt-dix-huit katr-vehn-dees-wheat ninety-eight quatre-vingt-dix-neuf katr-vehn-dees-noof ninety-nine At 100, everything starts all over again. The French word for “hundred” is cent; the other numbers are used after it to indicate the numbers between 101 and 199. Table 2-6 NUMBERS FROM 100 TO 199 FRENCH PRONUNCIATION ENGLISH cent sahn one hundred cent un sahn-un one hundred and one cent deux sahn-doo one hundred and two cent vingt sahn-vehn one hundred and twenty cent trente-deux sahn-trahnt-doo one hundred and thirty-two cent quatre-vingt-dix-neuf sahn-katr-vehn-dees-noof one hundred and ninety-nine To indicate more than one hundred, the appropriate word is inserted before cent. English does the same thing; the only difference between “one hundred” and “two hundred” is the number at the beginning of it. When the number is an even hundred, cent is used in the plural—it has an “s” on the end to show that more than one is being indicated. The “s” is not pronounced, but it is important to remember for written French. (You’ll find out more about uses of the plural in Chapter 5.) Table 2-7 NUMBERS FROM 200 TO 1,000 FRENCH PRONUNCIATION ENGLISH deux cents doo sahn two hundred deux cent deux doo sahn doo two hundred and two quatre cents katr sahn four hundred quatre cent quarante katr sahn karant four hundred and forty neuf cent soixante noof sahn swahz-ahnt nine hundred and sixty 28

- 29. One thousand follows the same pattern as one hundred, using the word mille. Dates also fall into this category, when referring to a year. Table 2-8 NUMBERS FROM 1,000 TO 2 MILLION FRENCH PRONUNCIATION ENGLISH mille meel one thousand mille neuf cent quatre-vingt-dix mee-yh noof sahn katr vehn dees nineteen ninety deux mille doo mee-yh two thousand deux mille un doo mee-yh uhn two thousand and one deux mille deux doo mee-yh doo two thousand and two dix mille dees mee-yh ten thousand cent mille sahn mee-yh one hundred thousand cent mille cent dix sahn mee-yh sahn dees one hundred thousand, one hundred and ten cinq cent mille sank sahn mee-yh five hundred thousand un million uhn mee-yohn one million deux million doo mee-yohn two million When talking about the year in spoken French, the numbers can be a mouthful. Consider: 1972: mille neuf cent soixant-douze (mee-yh noof sahn swahz-ahn-dooze) 1984: mille neuf cent quatre-vingt-quatre (mee-yh noof sahn katr vehn katr) 1998: mille neuf cent quatre-vingt-dix-huit (mee-yh noof sahn katr vehn dee-zwheat) Fortunately, current dates are much simpler, starting only with deux mille, which is easier both to remember and to pronounce. Ordinal Numbers Related to cardinal numbers are ordinal numbers, which are used to show a relationship between things or to indicate where a word happens to fit in a series. English examples are “first,” “second,” and “third.” In French, the word for “first” is the only ordinal number that must agree in gender and number with the noun it modifies. Table 2-9 THE ORDINAL “FIRST” GENDER SINGULAR PLURAL PRONUNCIATION Masculine premier premiers pruh-mee-yay Feminine première premières pruh-mee-aihr The rest of the ordinal numbers don’t change to agree with gender, but will still add an “s” to agree with a plural noun. Table 2-10 ORDINAL NUMBERS 29

- 30. FRENCH PRONUNCIATION ENGLISH deuxième duh-zee-ehmm second troisième twah-zee-ehmm third quatrième ka-tree-ehmm fourth cinquième sank-ee-ehmm fifth sixième see-zee-ehmm sixth septième set-ee-ehmm seventh huitième whee-tee-ehmm eighth neuvième noo-vee-ehmm ninth dixième dee-zee-ehmm tenth la troisième fois la twah-zee-ehmm fwa the third time You don’t have to memorize all of these numbers; you can learn to form them on your own. Ordinal numbers in French are formed using the cardinal number; this is very similar to the way English modifies numbers by adding “th” to the end of the cardinal number, creating “fourth” from “four,” “fifth” from “five,” “sixth” from “six,” and so on. To form the ordinal form of a number in French, simply drop the -e from the end of the cardinal number and add -ième to the end. If the cardinal number does not end in e, simply add the -ième ending to the word. This works for all numbers but these three: premier, which is unique when compared to the other ordinal numbers; cinquième, which adds a “u” after the “q”; and neuvième, which changes the “f” into a “v.” These last two changes are quite logical; without the changes, attempts at pronunciation would be nightmarish. In English, you commonly see ordinal numbers like “first” and “second” abbreviated in writing as “1st” and “2nd.” French does this too, but the small characters following the Arabic number are different. The number 1 is followed by a small er when it is abbreviated in the masculine, and a small re when abbreviated in the feminine. All others are followed by a small e. Table 2-11 ORDINAL NUMBERS ABBREVIATIONS FRENCH PRONUNCIATION ABBREVIATION ENGLISH premier (m) pruh-mee-yay 1er first première (f) pruh-mee-aihr 1re first deuxième doo-zee-ehm 2e second troisième twah-zee-ehm 3e third dix-huitième dee-zwee-tee-ehm 18e eighteenth You will often encounter these abbreviations in a variety of places: in newspapers, on signs, and in books and magazines. When you come across these abbreviations in written French, know that an ordinal number is intended. Dates Inevitably there are going to be some words you just have to learn to get by in French—little words, like days of the week and months of the year. You may find it helpful to read these word lists out loud a few times, memorizing them by rote. When said out loud in a series, these groups have a catchy rhythm, so it shouldn’t take you long to have them down pat. 30

- 31. Table 2-12 DAYS OFTHE WEEK FRENCH PRONUNCIATION ENGLISH lundi luhn-dee Monday mardi mahr-dee Tuesday mercredi mer-cruh-dee Wednesday jeudi juh-dee Thursday vendredi vahn-druh-dee Friday samedi sah-mu-dee Saturday dimanche dee-mahnsh Sunday Table 2-13 MONTHS OFTHE YEAR FRENCH PRONUNCIATION ENGLISH janvier jahn-vee-ay January février fayv-ree-ay February mars mahrs March avril ah-vreehl April mai may May juin jwehn June juillet jwee-ay July août ah-oot August septembre sep-tahm-br September octobre oc-tob-br October novembre no-vehm-br November décembre day-sehm-br December In written French, days of the week and months of the year are not capitalized, unless they happen to be used at the beginning of a sentence. 31

- 32. CHAPTER 3 Developing a Basic Vocabulary This chapter helps you master the little words that will add up to big results when you begin speaking to native French speakers. The chapter starts with conjunctions (in English, words such as “and,” “or,” and “but”), and then moves into a series of basic words and phrases that will help you assimilate in no time. 32

- 33. Conjunctions Conjunctions are words that are used to join parts of a sentence together. In English, common conjunctions are “and,” “or,” and “but.” You can use the following French conjunctions in the same way as English ones: donc (so, then, therefore) ensuite (next) et (and) ou (or) puis (then) mais (but) 33

- 34. Basic Words to Memorize The following vocabulary list includes a few basic words you can quickly master. They’re fairly easy to remember, and you’ll probaby find yourself using them extensively whenever you speak French. Table 3-1 BASIC FRENCH WORDS FRENCH PRONUNCIATION ENGLISH oui whee yes non nohn no bonjour bohn-jhoor hello excusez-moi eks-cyoo-zay-mwa excuse me s’il vous plaît seel-voo-play please merci mehr-see thank you merci beaucoup mehr-see bow-coo thank you very much Pardon? pahr-dohn Pardon me? Monsieur mohn-syoor Mr. Madame mah-dam Mrs. Mademoiselle mahd-mwa-zel Miss 34

- 35. Describing Things and People You can use a number of different phrases to refer to things and people, depending on the particular situation. This section describes the various constructions you can use. Il est In English, we often use the phrase “it is” to describe things: it is blue, it is old, it is hot. In French, this can be done using il est or c’est. Both forms can mean the same thing, ranging from “he is,” “she is,” or “it is,” depending on the construction of the sentence. Each form, however, is used at a different time. Il est is the correct choice in the following circumstances. If the subject of the sentence is female, then you may use elle est to make it agree. Using a Single Adjective When using a single adjective that refers to a specific person or a specific thing, il est is the proper construction. The adjective will agree in gender and number with the subject of the sentence. You can also use it in other tenses instead of just in the present. J’ai lu ce livre. Il a été bon. (I read this book. It was good.) J’aime ce jardin. Il est bien. (I love this garden. It is nice.) The phrase il est bon could also mean “he is good” in English. When translating, it is important to go to the heart of the meaning of the sentence and translate that, instead of trying to provide a word-for-word translation. Because pronouns are being used, you must determine which actual nouns they represent and derive the meaning from that. Referring to a Profession When simply stating that a person is of a certain profession, the phrase il est or elle est is used, and the noun appears with no article. English tends to use an indefinite article in its equivalent translation (see Chapter 4), so be careful. Elle est médecin. (She is a doctor.) Il est pharmacien. (He is a pharmacist.) Il est gendarme. (He is a police officer.) Referring to Nationalities When stating that a person is of a certain nationality, il est or elle est is used with the adjective, without any article. This more closely resembles the English construction, so it should seem straightforward to you. Remember that when a nationality is used in this fashion, it is not capitalized in French, because the word acts as an adjective. Only when a nationality is used as a noun is it capitalized. 35

- 36. Elle est française. (She is French.) Il est anglais. (He is English.) C’est The phrase c’est also means “it is,” but it is used in different circumstances from il est. It is a contraction of ce and est, and therefore doesn’t actually use a subject pronoun (see Chapter 9). Study its uses in this section, and then compare and contrast it with a later section so you understand the differences between the choices. With a Proper Name When you wish to refer to someone using his or her proper name, c’est is the appropriate choice, rather than il est. C’est Yvon Dumont. (It’s Yvon Dumont.) C’est Michel. (It’s Michael.) C’est Monsieur Allard. (It’s Mr. Allard.) With a Disjunctive Pronoun When wanting to say things like “it is me,” c’est is the proper construction. Technically, the proper English translation should be “it is I,” because when object pronouns are used with the verb “to be” they are supposed to be identical to the subject. The proper English rules are often not followed, however, so choose the translation that seems to make the most sense. C’est moi. (It is me.) C’est toi. (It is you.) C’est elle. (It is her.) When Referring to a Situation or Idea C’est is often used with a singular masculine adjective to refer to states of being or ideas. Oui, c’est vrai. (Yes, that’s right.) J’acheterai le livre, c’est certain. (I will buy the book, it’s certain.) When Referring to a Noun That Is Modified by Other Words When a noun is used with adjectives that modify or refine the meaning of the noun, c’est is the appropriate choice. Even a single article used with a noun is enough to modify it and make it necessary to use the c’est construction. C’est un livre excellent. (It’s an excellent book.) C’est une pomme. (It’s an apple.) 36

- 37. Il y a In English, we often use phrases like “there is” or “there are” to refer to the general existence of things. In French, this is done with the phrase il y a. The French word y is an object pronoun (see Chapter 9). In this construction, it is the rough equivalent of the English “there.” Even when il y a is used with a plural object, the subject and verb don’t change. This is a French idiomatic expression that does not translate literally, so don’t try to put it in the plural when referring to more than one object. It doesn’t change for feminine objects, either; il is still used in the construction, even when referring to something feminine. Il y a un bon film au cinéma. (There is a good film at the theatre.) Il y a une grande vedette en ville. (There is a big star in town.) You can also use the construction il y a as a question to ask if something exists. You could use the phrase est-ce que in front of it to form the question, or you can use inversion (see Chapter 7). When inversion is used, however, the pronoun retains its regular position in front of the verb, so you must insert a “t” in between. Y a-t-il un bon film ici? (Is there a good film here?) Y a-t-il une femme ici? (Is there a lady present?) Voilà Voilà is used to indicate something specific. It is actually a preposition that means “there is,” “there are,” or even “that is.” Rather than merely pointing out its existence the way il y a does, voilà points specifically to the item being indicated when used at the beginning of the sentence. It is like actually pointing to an item with your finger; as a general rule, voilà should be used only when pointing your finger would be an appropriate gesture to accompany the statement. If you look at the following sentences carefully, there isn’t actually any verb used. Voilà takes the place of both the subject and the verb, being used only with the object of the sentence. When translating into English, simply choose the form that makes the most sense. Voilà les enfants. (There are the children.) Voilà une fenêtre. (There is a window.) Because voilà doesn’t really use a verb, you don’t have to worry about agreement with any of the words; any articles must still agree with the nouns, however. 37

- 38. CHAPTER 4 Understanding Articles In English, we often say things like “the book” or “a library.” “The” and “a” are known as articles. The word “the” or “a” introduces a noun and serves a grammatical purpose by showing how the word is to be treated in the sentence—whether it is referring to a specific object or referring to things in a more general sense. It tells you how the noun fits and relates to the other words in the sentence. 38

- 39. Discovering French Articles French articles work just like English articles, except that the articles change slightly for masculine or feminine nouns, plural or singular nouns, and (like English) nouns that begin with vowels. In English, the definite article can often be dropped or ignored, but in French, articles are very much a necessity to proper communication. French articles usually become a part of the word—before too long, you’ll barely even notice them. In some ways, it will be helpful to you to think of articles as a part of the words themselves rather than an additional piece that needs to be memorized. As a matter of fact, when learning a noun, memorize the article along with it—this will save you from looking the gender of nouns up later (see Chapter 5). “The” is called a definite article, because you use it to indicate a certain, specific item, as opposed to something in general. In French, the definite article can take one of four forms: le: when used before a word with masculine gender la: when used before a word with feminine gender l’: when used before a word that starts with a vowel or silent “h” les: when used to indicate a group or more than one of an item You can use articles to help you remember the gender of nouns when the noun begins with a vowel. Because gender is mostly a matter of memorization, the indefinite article will tell you the gender, leaving one less thing to memorize. With indefinite articles, the exact item is not known; examples of this are “a car” or “an apple.” There are three forms of indefinite articles in French: un: when used before a word with masculine gender une: when used before a word with feminine gender des: when used to indicate a group or more than one of an item 39

- 40. The Definite Article As a general rule, any time the word “the” is used in English, the definite article will be used in French: le, la, and les. All are the equivalent of “the” in English. Le is the masculine form, la is the feminine, and les is used for plural nouns of either gender. The definite article should not be translated literally. The rules for article usage differ slightly in each language; sometimes, it will not be required in an English sentence, while its presence is necessary in French. Keep the following points in mind, and you should find that learning and understanding definite articles pose no problems for you at all. Before a Vowel Whenever le or la precedes a word starting with a vowel or a silent “h,” it becomes l’. l’eau (f) (pronounced low), means “water” l’écran (m) (pronounced lay-krahn), means “screen” l’heure (f) (pronounced leur), means “hour” When translating, never simply replace le or la with “the.” Whenever you see an article being used in either language, look to the noun and translate that. If the noun requires an article in the translated sentence, only then should it be used. Nouns in a Series When referring to nouns in a series, each noun must have the corresponding definite article: J’ai le lait, le pain, et la moutarde. (I have the milk, the bread, and the mustard.) People When using a noun that refers to a person, the definite article is used. If you are addressing that person directly, however, no article is used. Le professeur a un livre. (The professor has a book.) Monsieur professeur, avez-vous un livre? (Mr. Professor, do you have a book?) Seasons When referring to seasons, the definite article is usually used in front of the noun. la saison (season) 40

- 41. le printemps (spring) l’été (m) (summer) l’automne (m) (autumn) l’hiver (m) (winter) Languages Names of languages are used with a direct article, except with the verb parler. Chapter 2 gives you the phrase, parlez-vous anglais? The verb parler, which means “to speak,” does not use a definite article when referring to a language. le français (French) l’anglais (m) (English) l’espagnol (m) (Spanish) l’allemand (m) (German) le portugais (Portuguese) l’italien (m) (Italian) le chinois (Chinese) le japonais (Japanese) le russe (Russian) 41

- 42. The Indefinite Article Indefinite articles are used when one is referring in general to an item. In English, the indefinite articles are “a” and “an,” and the French indefinite articles are very similar: un, une, and des. Un and une are equivalent to “a” in English. Des, the plural, can mean “some” or “any” in English, and is used with plural nouns of either gender. Indefinite articles are pretty well interchangeable with direct articles; the choice depends on the sense in which the noun is meant. If you are referring to something specific, the direct article is the appropriate choice. When you’re referring to things in general terms, use the indefinite article. 42

- 43. The Partitive Article French also has a unique class of articles, known as the partitive, that is used when the exact quantity of an item is not known. It conveys the sense of “some” or “any.” The partitive is a grammatical distinction that doesn’t really exist in English, so you may have to watch yourself in the beginning to make sure that you are using the right article. In English, we can say, “He has eggs.” Inferred in the statement is the word “some”—in fact, the sentence “He has some eggs” means basically the same thing. In English, the “some” is often omitted entirely. In French, however, these words cannot be ignored; the partitive article is required to convey proper meaning. It is known as the partitive because it describes only a part of the object and not the object as a whole. Whenever the sense of “some” or “any” is inferred in the sentence, the partitive article must be used. The partitive is signaled by the word de in French. De is a preposition that has a great many other uses; you’ll learn more about it in the next section. One of its most important uses, however, is in the partitive, along with the definite article. Whenever you see de or one of its contractions, ask yourself which sense is meant—whether something in its entirety is meant or only a small part of it. If it’s only a small part, the English equivalent is probably “some” or “any,” and, therefore, the word takes the partitive in French. The partitive is formed by combining de and the definite article. de + le = du: when used before singular nouns with masculine gender de + la = de la: when used before singular nouns with feminine gender de + l’ = de l’: when used before singular nouns that begin in a vowel or silent h de + les = des: when used before plural nouns of either gender Suppose you’re talking to a friend who invites you over to her place for coffee. You hope she has milk, so you could ask any of the following in English: Do you have any milk? Do you have milk? Do you have some milk? Because you are only referring to a small amount of all the milk available, “some” is meant, so the partitive is used in French, as follows: As-tu du lait? Similarly, suppose you are getting together with your friend to bake a triple-layer cake, and you are going over the list of ingredients, deciding who will supply which ingredients. Wondering if she has the milk that the recipe calls for, you want to ask, “Do you have the milk?” Because milk is being referred to in a specific sense, the definite article is used, rather than the partitive article: As-tu le lait? You aren’t asking whether your friend has some milk, or any milk, or enough milk—you’re asking whether she has the specific amount of milk that the recipe calls for. Because you mean it in a specific sense, the partitive does not get used; the direct article is used, instead. Pay particular attention to the amount when choosing which article to use. If you use a definite article when the partitive is required, native French speakers may become terribly confused, trying to figure out what you mean. For example, if you asked, As-tu le lait? when you meant to ask only for some, your listeners will be trying to figure out which milk you mean—whether it’s all the milk in the world or another specific amount. 43

- 44. Partitive Article in Negative Expressions As you may recall from Chapter 2, ne … pas can be used to make an expression negative. It is the equivalent of the English word “not.” There are other ways to make a statement negative (see Chapter 8). When the partitive is used in a negative expression, de appears alone, without the definite article. Whether the noun being used in the partitive is masculine or feminine, the only word appearing before it will be de. Masculine: As-tu du lait? (Do you have some milk?) Non, je n’ai pas de lait. (No, I don’t have any milk.) Feminine: As-tu de la farine? (Do you have any flour?) Non, je n’ai pas de farine. (No, I don’t have any flour.) Naturally, there’s an exception. When using être, the verb “to be,” the proper partitive article is always used, whether the sentence is negative or not. Say you wrap some cake up for a friend; when you give it to him, he asks, “What is it?” You could answer this way: C’est du gâteau. (It is some cake.) Remember that in the negative, the verb être uses the regular partitive article. Say your friend asks if there is water in your glass: Ce n’est pas de l’eau. C’est de la bière. (No, it’s not some water. It’s some beer.) In the negative, notice that de l’eau includes both de and the definite article, because l’eau is a feminine word. The partitive is used in full because it appears with the verb être. If another verb were being used in the negative, only de would be used. Etre is the only verb that uses the regular partitive article in a negative expression; all other verbs, including avoir, simply use de alone as the partitive article. Plural Uses of the Partitive Article Des, you’ll remember, is normally the plural indefinite article. In the partitive, it is used only with words that are always plural. Therefore, if you know that a noun can be used in the singular, des will always be the plural indefinite article. If the noun only has meaning in the plural, however, des will indicate that the noun is being used in the partitive sense. Say you and a friend are thinking about going on a trip, and he asks if you have any holiday or vacation days: As-tu des vacances? (Do you have any holidays?) Because your friend is referring to vacation days in general, the partitive is used: Oui, j’ai des vacances. (Yes, I have some.) If you didn’t have any available vacation days, you would answer in the negative: Non, je n’ai pas des vacances. 44

- 45. CHAPTER 5 Using Nouns Noun is the grammatical term for a word that designates a person, place, thing, or idea. In French, a noun is known as a nom, which also happens to be the same word for “name.” That’s actually a good way to remember it—a noun is simply the name of a person, place, thing, or idea. 45

- 46. Understanding Nouns There are two general types of nouns: concrete and abstract. A noun is concrete when it describes something definite, like a person, place, or thing. Ideas and emotions are also nouns, but these are considered abstract. Nouns can be used in sentences in a number of ways. They can appear as the subject of a verb, performing the action described in the sentence, or they can appear as the object and receive the action of the sentence, either directly or indirectly. Subject: The girl is walking. Direct object: I found the girl. Indirect object: I gave the puppy to the girl. The same noun can be used to convey a variety of different meanings. French, like English, relies on word order and auxiliary words to show how the noun is affected by the sentence. You’ll learn more about the uses of direct and indirect objects in Chapter 9. There are other kinds of nouns, too. Pronouns are words that replace nouns, such as “him” or “her.” Pronouns are used in place of a noun; in the first of the preceding examples, the word “she” could replace “the girl,” and the word “her” could be used instead as the direct object or indirect object. Pronouns can be used in all of these instances (see Chapter 9). In this chapter, you’ll learn some French nouns and how they are used. Don’t strain yourself in memorizing all of them. If you read over the vocabulary sections periodically, you should find that you are becoming more and more familiar with the words. 46

- 47. Gender of Nouns One of the biggest differences you’ll notice between French and English is the use of gender. Each noun in French will either have a feminine or masculine gender. This a linguistic trait inherited from Latin, where there could be three categories of gender: masculine, feminine, and neuter. French has only two: masculine and feminine. The gender designation in French is rather arbitrary. There isn’t necessarily much logic as to whether a noun will be masculine or feminine, nor are there any hard-and-fast rules. There are some general pointers, which you can find in this chapter, but in the end, the advice is always the same: Memorize the gender of a word as you learn it. Don’t let yourself get confused about the concept of gender in French. It refers only to the noun as a word; it does not necessarily indicate the sex of the person indicated by the noun. Gender is a grammatical concept and has nothing to do with the biological sex of the object or person involved. The gender of a noun is important to know; it can affect how the word is used and how other words are used along with it. The French Academy has long upheld the use of gender in the French language, and language purists defend its usage on historical grounds. As long as you remember that it’s only a grammatical concept, you should have no trouble with it at all. In this book, nouns are presented with the article (or, if the article is ambiguous, you’ll find a small “m” for masculine and a small “f” for feminine nouns). You can also consult a French-English dictionary, which will indicate the gender of a particular word for you. While there are no hard-and-fast rules about determining the gender of nouns, the majority of French words follow a consistent gender pattern. In addition to the noun’s article, the ending can sometimes help you determine the proper gender of a noun. The following lists give you the chance to become familiar with some French nouns, their endings, and their gender. These lists are only guidelines, of course; there will always be exceptions (some notable ones are included in the lists). Masculine Nouns This section helps you determine which nouns are masculine by looking at their endings. Table 5-1 NOUNS ENDING IN -AIRE NOUN PRONUNCIATION ENGLISH le dictionnaire le deek-syo-nehr dictionary le propriétaire le pro-pree-ay-tehr owner le vocabulaire le vo-cab-yoo-lehr vocabulary la grammaire* la gram-mehr grammar * Exception to this ending. 47

- 48. Table 5-2 NOUNS ENDING IN -ASME AND -ISME NOUN PRONUNCIATION ENGLISH le sarcasme le sar-kasm sarcasm l’optimisme lop-tee-meesm optimism le pessimisme le pess-ee-meesm pessimism le tourisme le too-reesm tourism Table 5-3 NOUNS ENDING IN -É NOUN PRONUNCIATION ENGLISH le blé le blay wheat le café le kah-fay coffee l’employé lom-ploy-ay employee le pavé le pah-vay pavement Many words that end in -té are exceptions. Table 5-4 NOUNS ENDING IN -EAU NOUN PRONUNCIATION ENGLISH le bateau le bah-tow boat le bureau le boo-row office le chapeau le shah-po hat l’eau (f)* low water * Exception to this ending. Table 5-5 NOUNS ENDING IN -ET NOUN PRONUNCIATION ENGLISH l’alphabet lal-fa-bay alphabet le billet le bee-yay ticket le juillet le jhwee-ay july l’objet lob-jhay object le sujet le soo-jhay subject Table 5-6 NOUNS ENDING IN -IEN 48

- 49. NOUN PRONUNCIATION ENGLISH le chien le shee-ehn dog le magicien le mah-jee-syen magician le musicien le moo-zee-syen musician le pharmacien le far-meh-syen pharmacist Table 5-7 NOUNS ENDING IN -IN NOUN PRONUNCIATION ENGLISH le bain le behn bath le cousin le koo-zehn cousin le juin le jwehn june le magasin le may-gah-zehn shop le matin le mah-tehn morning le vin le vehn wine Table 5-8 NOUNS ENDING IN -NT NOUN PRONUNCIATION ENGLISH l’accent lax-sahn accent l’accident lax-see-dahn accident l’argent lar-jhahn money Table 5-9 NOUNS ENDING IN -OIR NOUN PRONUNCIATION ENGLISH l’espoir less-pwar hope le miroir le mee-rawr mirror le rasoir le rah-zwar razor le soir le swahr evening In written French, personal titles are often abbreviated. In spoken French, the full word is always pronounced. SINGULAR ABBREVIATION PLURAL ABBREVIATION Monsieur M. Messieurs Mssrs. Madame Mme Mesdames Mmes. Mademoiselle Mlle Mesdemoiselles Mlles. 49

- 50. Feminine Nouns You can often determine which nouns are feminine by looking at the endings. Table 5-10 NOUNS ENDING IN -ADE NOUN PRONUNCIATION ENGLISH la limonade la lee-mo-nad lemonade la parade la pahr-ad parade la promenade la prom-nad walk la salade la sal-ad salad Table 5-11 NOUNS ENDING IN -AISON NOUN PRONUNCIATION ENGLISH la maison la meh-zohn house la raison la rez-ohn reason la saison la sez-ohn season Table 5-12 NOUNS ENDING IN -ANCE NOUN PRONUNCIATION ENGLISH l’assistance lass-ee-stahns assistance la balance la bal-ahnss balance la chance la shahns chance la naissance la ness-ahns birth la vacance la vek-ahns vacancy Table 5-13 NOUNS ENDING IN -ENCE NOUN PRONUNCIATION ENGLISH la différence la dee-fay-rahns difference l’essence less-ahns gasoline la science la see-ahns science la sentence la senn-tahns sentence l’excellence (m)* lex-say-lahns excellence le silence* le see-lahns silence * Exceptions to this ending. Table 5-14 NOUNS ENDING IN -ANDE 50

- 51. NOUN PRONUNCIATION ENGLISH la commande la com-ahnd command la demande la duh-mahnd request la viande la vee-ahnd meat Table 5-15 NOUNS ENDING IN -ISE NOUN PRONUNCIATION ENGLISH l’église lay-gleez church la fraise la frez strawberry la surprise la sur-preez surprise la valise la vall-eez suitcase Table 5-16 NOUNS ENDING IN -SON NOUN PRONUNCIATION ENGLISH la boisson la bwa-sohn drink la prison la pre-zohn prison la chanson la shahn-sohn song Table 5-17 NOUNS ENDING IN -TÉ NOUN PRONUNCIATION ENGLISH la beauté la boh-tay beauty la cité la see-tay city la liberté la lee-behr-tay liberty la nationalité la nah-see-yo-nal-ee-tay nationality le côté* le ko-tay side l’été (m)* lay-tay summer * Exception to this ending. Table 5-18 NOUNS ENDING IN -TIÉ NOUN PRONUNCIATION ENGLISH l’amitié lam-ee-tyay friendship la moitié la mwhah-tyay half la pitié la pee-tyay pity Table 5-19 NOUNS ENDING IN -UDE 51

- 52. NOUN PRONUNCIATION ENGLISH l’étude lay-tood study l’habitude lab-ee-tood habit la solitude la soll-ee-tood solitude Table 5-20 NOUNS ENDING IN -TURE NOUN PRONUNCIATION ENGLISH l’aventure la-vahn-choor adventure la ceinture la sayn-choor belt la culture la cul-choor culture la facture la fak-choor invoice la nourriture la new-ree-choor food, nourishment Some Special Gender Notes As a rule, most French nouns require a specific gender. Some nouns, however, can use either gender but have two different meanings, depending on the particular gender used. In the masculine, the word will have one meaning, but the feminine will mean something else. Table 5-21 NOUNS WITH DIFFERENT GENDER MEANINGS MASCULINE ENGLISH FEMININE ENGLISH le livre (le lee-vruh) book la livre (la lee-vruh) pound le manche (le mahnsh) handle la manche (la mahnsh) sleeve le mode (le muhd) mode la mode (la muhd) fashion, manner, way, custom le poste (le pohst) post la poste (la pahst) mail, postal service le vase (le vahs) vase la vase (la vahs) mud, slime le voile (le vwahl) veil la voile (la vwahl) sail 52

- 53. Plural Nouns Whenever you talk about more than one of something, the noun must be used in the plural. In English, turning most nouns into a plural form is fairly easy—we usually just add an “s” to the end of the word. Some English words, however, change quite a bit when referring to the plural. Table 5-22 ENGLISH PLURAL NOUNS SINGULAR PLURAL child children foot feet man men phenomenon phenomena wolf wolves You may not even think about these differences—they come naturally as part of the English language. After you know a few nouns in French, though, when you come across a new word, you’ll be able to determine its plural form by comparing it to the similar nouns you already know. If you get really stuck on a plural form, you can always check a dictionary. Fortunately, most nouns follow fairly simple rules for the formation of the plural. Most nouns will simply add an “s” to the end of the noun to make the plural form. Other nouns, however, may pose more difficulty. French nouns can have a great variety of endings, and some of the plural forms are made in unique ways. This section shows the rules for forming the plural and also indicates some exceptions you may encounter. Nouns Ending in -s, -x, or -z If the noun already ends in -s, -x, or -z, no change occurs; a plural article is simply used with a word to indicate the plural. Table 5-23 NOUNS ENDING IN -S, -X, OR -Z SINGULAR PLURAL ENGLISH le fils (le feece) les fils (lay feece) son(s) le repas (le re-pah) les repas (lay re-pah) meal(s) la toux (la too) des toux (day too) cough(s) le prix (le pree) les prix (lay pree) prize(s) le nez (le nay) les nez (lay nay) nose(s) Nouns Ending in -ail Most nouns ending in -ail add an “s” at the end of the word to form the plural. Table 5-24 NOUNS ENDING IN -AIL 53

- 54. SINGULAR PLURAL ENGLISH l’éventail (lay-vahn-tie) les éventails (lay vahn-tie) fan(s) le détail (luh day-tie) les détails (lay day-tie) detail(s) A few nouns ending in -ail don’t follow the regular rules, dropping the -ail and adding -aux to the end instead. Table 5-25 IRREGULAR NOUNS ENDING IN -AIL SINGULAR PLURAL ENGLISH le bail (le by) les baux (lay bo) lease(s) le corail (le ko-rye) les coraux (lay ko-ro) coral(s) l’émail (le ay-my) les émaux (lay-say-mo) enamel(s) le soupirail (le soo-pee-rye) les soupiraux (lay soo-pee-ro) ventilator(s) le travail (le tra-vye) les travaux (lay tra-vo) work(s) le vitrail (le vee-try) les vitraux (lay vee-tro) stained-glass window(s) Nouns Ending in -eau For nouns ending in -eau, simply add an “x” to the end of the noun. Table 5-26 NOUNS ENDING IN -EAU SINGULAR PLURAL ENGLISH le couteau (le coo-tow) les couteaux (lay coo-tow) knife/knives le cadeau (le cah-dew) les cadeaux (lay cah-dew) gift(s) le gâteau (le gah-tow) les gâteux (lay gah-tow) cake(s) Nouns Ending in -eu For nouns ending in -eu, add an “x” to the end of the noun. Table 5-27 NOUNS ENDING IN -EU SINGULAR PLURAL ENGLISH le jeu (luh jhoo) les jeux (lay juh) game(s) le feu (luh fuh) les feux (lay foo) fire(s) Nouns Ending in -al For nouns ending in -al, the ending is changed to -aux. 54

- 55. Table 5-28 NOUNS ENDING IN -AL SINGULAR PLURAL ENGLISH l’animal (lah-nee-mahl) les animaux (lay-zahn-mo) animal(s) le canal (le kah-nahl) les canaux (lay kah-no) canal(s) le journal (le jhoor-nahl) les journaux (lay jhoor-no) newspaper(s) Nouns Ending in -ou For nouns ending in -ou, add an “x” to the end of the word. Table 5-29 NOUNS ENDING IN -OU SINGULAR PLURAL ENGLISH le bijou les bijoux (lay bi-joo) jewel(s) le chou les choux (lay choo) cabbage(s) le genou les genoux (lay jhen-oo) knee(s) le hibou les hiboux (lay ibo) owl(s) Nouns That Are Always Plural Some French nouns are always used in the plural sense; the singular either doesn’t exist or means something different. Table 5-30 NOUNS THAT ARE ALW AYS PLURAL PLURAL NOUN PRONUNCIATION ENGLISH les gens lay jhan people les mathématiques lay mah-tay-ma-teek mathematics les vacances lay vah-kahns vacation les frais lay freh expenses When referring to vacations, the term les vacances must always be used in the plural. Even if you are only referring to one particular vacation or a single day of vacation, les vacances must be used. La vacance, the singular form of the word, means “vacancy.” Family Names When the noun is a family name, nothing is added. It is used on its own, without turning the noun itself into a plural form; the plural is inferred from the article. Other words, such as verbs, that are used with the noun will also be used in the plural sense to agree with it. 55

- 56. les Dumont (the Dumonts; the Dumont family) les Lasalle (the Lasalles; the Lasalle family) Irregular Plurals Some words undergo a bit of a transformation or even change entirely in the plural sense. These are irregular plurals. Table 5-31 IRREGULAR PLURALS SINGULAR PLURAL ENGLISH l’œil (loy) les yeux (layz-yeuh) eye(s) Monsieur (mohn-syeuhr) Messieurs (may-syeuhr) Mr., gentlemen Madame (mah-dahm) Mesdames (mah-dahm) Mrs., ladies Mademoiselle (mah-de-mwah-zell) Mesdemoiselles (may-de-mwah-zell) Miss(es) 56

- 57. CHAPTER 6 Forming Present-Tense Verbs This chapter gets you into verbs, specifically those in the present tense. Building on the articles and nouns in the two preceding chapters, you can use the information in this chapter to create full sentences! While forming the verb in the present tense is easier than for the past and future tenses, verbs can still be a challenge. This chapter simplifies the process. 57

- 58. Verb Forms: The Infinitive You’ve probably noticed that when you refer to verbs in English, the verb is prefaced by the word “to.” “To go,” “to be,” and “to speak” are examples. The “to” tells you that the verb is being used in a general sense, not tied to a particular subject. Because these verbs don’t have a subject or object, they are said to be in the infinitive. I don’t like to drive. I love to walk. I want to go. In French, nothing is placed before the word in the infinitive. As a matter of fact, you have likely already learned many infinitive French verbs. The infinitive in French is simply the unconjugated form of the verb you have probably already seen throughout the book: avoir (to have) aimer (to love) être (to be) écouter (to listen) parler (to speak) nager (to swim) Occasionally, you may come across signs in French that say things like Ne Pas Fumer. At first, they may seem confusing, as it appears to read “not to smoke.” This is just the French way of doing things, but think about it like this: Because the sign doesn’t know who is going to be reading it, it keeps the verb in the infinitive; that way, it can apply to everyone. 58