‘Calvin and Hobbes’ said goodbye 25 years ago – here’s why Bill Watterson’s masterwork enchants us still

“A new year … a fresh, clean start!” a joyous boy in red mittens said a quarter-century ago this week shortly before soaring forth on the most famous sled in American arts this side of “Citizen Kane.” And just like that, the high-spirited 6-year-old and his best buddy were never seen again – at least not in new images. Yet the beloved duo have never really left us.

“Calvin and Hobbes,” one of the greatest strips ever to grace newspapers, blazed across the pages for a beautiful decade before heading off into the white space of our imaginations, trusting us to continue the next adventures in our heads. And to this day, the creation – once syndicated to 2,000-plus papers – is ever-present on bestseller lists, in libraries and nested on home shelves within easy reach of nostalgic adults and each next generation of young readers.

Decades later, the brilliance of “Calvin and Hobbes” refuses to dim. It remains a tiger – the tiger – burning bright. The final “Calvin and Hobbes” strip was fittingly published on a Sunday – Dec. 31, 1995 – the day of the week on which creator Bill Watterson could create on a large color-burst canvas of dynamic art and narrative possibility, harking back to great early newspaper comics like “Krazy Kat.” The cartoonist bid farewell knowing his strip was at its aesthetic pinnacle.

“It seemed a gesture of respect and gratitude toward my characters to leave them at top form,” Watterson wrote in his introduction to “The Complete Calvin and Hobbes” box set. “I like to think that, now that I’m not recording everything they do, Calvin and Hobbes are out there having an even better time.”

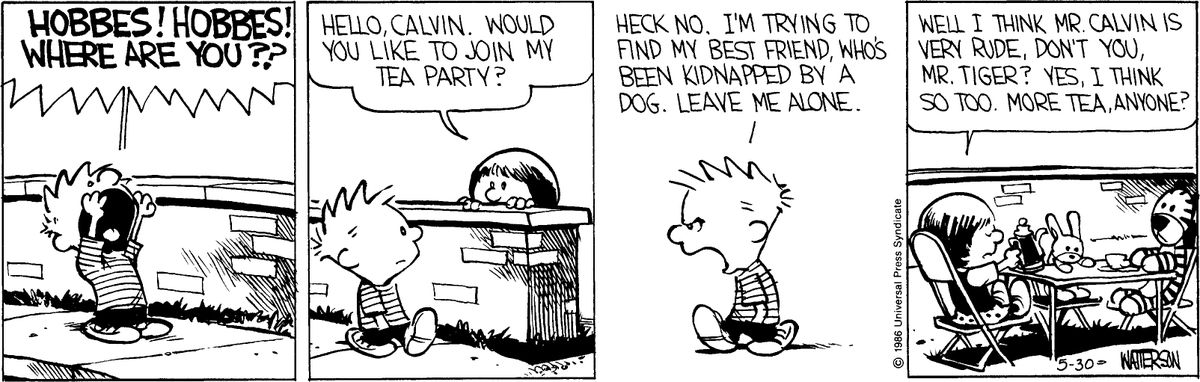

Readers return that respect. Ask a fan for a favorite “Calvin and Hobbes” scenario, and a stream of recurring comic premises pours forth.

“Spaceman Spiff, Tracer Bullet, Calvinball, G.R.O.S.S., the wagon rides, Calvin’s battles with his food, Calvin’s epic confrontations with (babysitter) Rosalyn, the cardboard-box inventions, Stupendous Man – and that’s just off the top of my head,” says curator Andrew Farago, whose Cartoon Art Museum in San Francisco has exhibited Watterson’s original art. “I don’t think any strip since ‘Peanuts’ made such an impact on so many people.”

Just what is it about “Calvin and Hobbes” that continues to enchant so many?

For some fans and fellow artists, it begins with the comic’s sense of boundless imagination. A fresh snow is like “having a big white sheet of paper to draw on!” says Hobbes in the final strip. That dialogue reflects the comic’s sheer joy in taking readers on wild rides, exploring the creative possibilities with youthful abandon.

Watterson’s ability to tap into childhood, including his own memories, propels Calvin’s flights of fancy, whether he is climbing into a capsule as Spaceman Spiff (facing down alien overlords as stand-ins for Calvin’s real-life authority figures) or imagining himself to be a fearsome beast.

Stephan Pastis, creator of “Pearls Before Swine,” views Calvin as an expression of pure childlike id, yet thinks there is a whole other dynamic that makes many of Calvin’s acts of imagination so appealing.

Watterson “accurately captured how put-upon you feel as a kid – how limited you are by your parents, by your babysitter, by (schoolteacher) Miss Wormwood. You’re really boxed in, and all you have is individual expression,” says Pastis, who collaborated with the “Calvin and Hobbes” creator on a week of “Pearls” strips in 2014, marking Watterson’s only public return to the comics page since 1995.

“I think that’s why to this day, some people get (Calvin) tattooed on their bodies,” Pastis continues. “He stands for that rebellious spirit in the fact of a world that kind of holds you down. You get into adulthood, you get held down by your various responsibilities. Calvin rebels against that, therefore he always remains a hero.”

Calvin’s irrepressible nature is often comedically set against would-be toy tiger Hobbes, who, alive through Calvin’s eyes, holds forth as the voice of reason – leading to art that revels in both the physical and the philosophical.

In one day’s strip, Calvin and Hobbes might engage in, say, a ballet of physical comedy – the stretch and squash effects rendering the strip as near to animation as a static art form can. The next day, by contrast, our buddy-comedy protagonists might muse on themes befitting a comic-strip title that name-checks two lofty thinkers.

“My 8-year-old son tends to laugh out loud at the physical humor, like when Hobbes pounces on Calvin, or his mother’s mystery dinner attacks him,” says Jenny Robb, who curated a 2014 “Calvin and Hobbes” retrospective at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum, which holds almost all of Watterson’s art in its collection, in his home state of Ohio.

Yet one of her son’s favorite strips is “where Calvin saves a snowball in the freezer for months, then throws it at” neighborhood girl Susie Derkins – but misses, says Robb, noting that “the more philosophical ones give us something to discuss when we read them together.”

Those philosophical ones even deal with mortality in an especially tender way, such as when Calvin comes upon a dead bird and says, “Once it’s too late, you appreciate what a miracle life is.” Or when he asks, “Hobbes, do you think our morality is defined by our actions, or by what’s in our hearts?”

“The series I remember the most was when the baby raccoon died,” says CNN anchor Jake Tapper, a comic-art collector and former college cartoonist. “That was a weeklong series about loss that was very moving” and “planted itself in my soul.”

Daveed Diggs, the “Hamilton” and “Soul” star who co-created viral webisodes in 2014 that acted out “Calvin and Hobbes” strips, says that Watterson was able to address “adult existential angst in the bodies of this kid and tiger.”

As “Calvin and Hobbes” evolved, so did Watterson’s virtuosic abilities to render everything from kinetic action to spot-on facial expressions to panoramic long shots.

“I don’t think any cartoonist since Walt Kelly has been able to make nature as gorgeous as Watterson – you’d have to go back to the swamps of the Okefenokee,” says Tapper, citing the creator and the setting of the classic strip “Pogo.”

Dave Kellett, a comics documentarian and creator of the strip “Sheldon,” especially relishes Watterson’s half-page Sundays created during the latter half of the strip’s run.

“His beautiful vistas of the American Southwest, his energetic panels taking you through Ohio forests, his experiments with brush and pen that really shined with the increased real estate – those are some of the most beautiful newspaper comics ever made,” says Kellett, whose 2014 film “Stripped” was a love letter to the form. “They probably go toe to toe with the greatest pages Winsor McCay ever produced for ‘Little Nemo in Slumberland.’ ”

So many 20th century comics feel embalmed in their era because of topical references or period-specific jargon and humor, but 35 years after its launch, the spirit of “Calvin and Hobbes” feels snowflake fresh. Sure, the strip knowingly decorated its interiors with throwback furniture – Watterson noted how fun it was to draw mid-century styles – but little else looks antiquated.

“Everything having to do with ‘Calvin and Hobbes’ expressed my own ideas, my own values, my own way,” Watterson wrote in his box-set introduction. “I wrote every word, drew every line and painted every color.

“It’s a rare gift to find such fulfilling work, and I tried to show my appreciation by giving the strip everything I had to offer.”