Eight thinking map PDF templates, plus PDF lesson plan

KS1, KS2

Years 1-6

If you’re still only using sheets of differentiated questions to develop reading comprehension, it’s time to update your practice with thinking maps, says Nikki Gamble…

It’s 10am on Monday and the literacy lesson in Green class is in full swing. The children are well-organised and appear to be working purposefully on the task at hand.

Each child has a photocopied passage (differentiated for various reading abilities). They work through a set of related questions that address the old assessment focuses.

Answers are written neatly in an English exercise book. As I ask one child what she is doing, she explains, “It’s a comprehension”.

Perhaps this practice sounds familiar to you.

It has certainly been a well-established way of teaching, stretching back to the beginning of the last century – but is it an approach we should still be using, especially as we now know so much more about developing reading comprehension?

Assessing background knowledge with thinking maps

A group of schools in Richmond has been focusing on developing reading comprehension in the upper primary years using well researched, evidence-based teaching strategies.

One of the key elements has been the use of visual organisers to structure the thinking process of children.

This visual representation approach allows classroom teachers to assess pupils’ prior knowledge and understanding. They can then plan the appropriate next steps so that learning is both deepened and accelerated.

At one of the participating schools, East Sheen Primary, thinking maps (developed by Dr David Hyerle) are used across the whole curriculum by every child from Reception to Year 6.

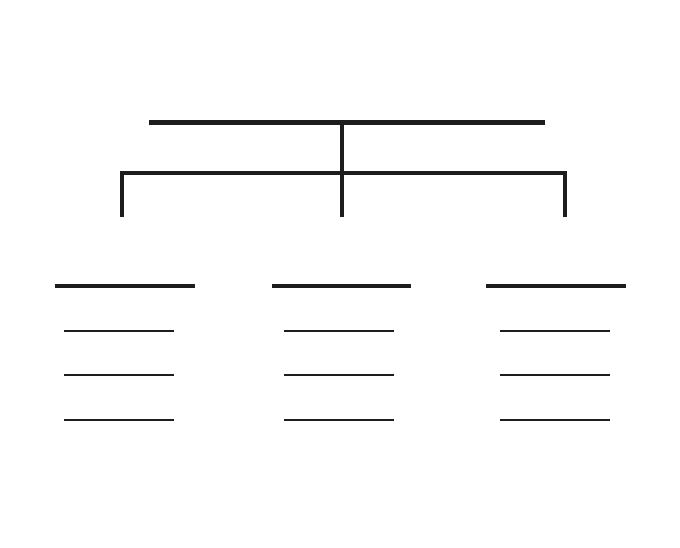

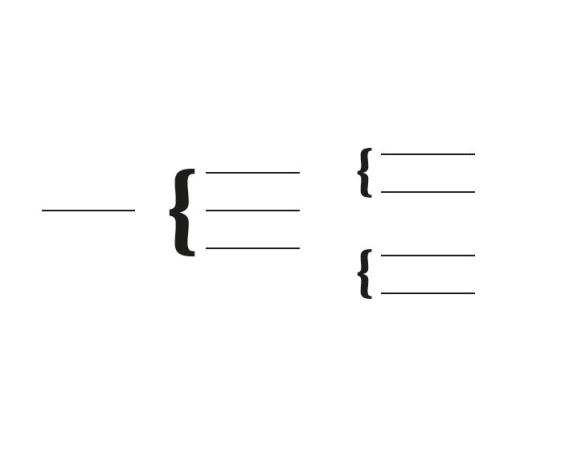

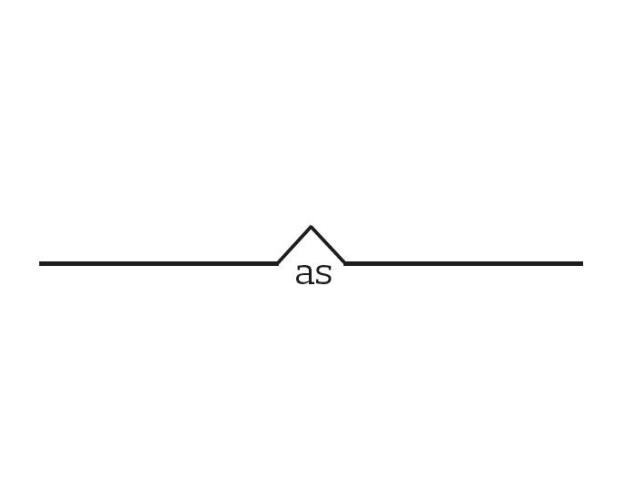

The school uses eight thinking maps in total, and each is used to develop a different thought process.

The space around the thinking map is called the ‘frame of reference’. Here we record how we came to know the information recorded on each map. Did we, for example, learn this from reading the book, watching a video, or from teachers and parents?

This encourages school students to be reflective about what they are learning. They need to consider not only what they know, but also how they know it, and the relationships between ideas.

In terms of reading, this is an introduction to identifying sources, which older children can develop further by making judgements about the reliability and validity of those sources.

Using thinking maps for deeper learning

Here are the eight thinking maps being used by East Sheen Primary. It’s important to decide which type of thinking map best suits your objective.

Download the eight thinking map templates at the top of this page.

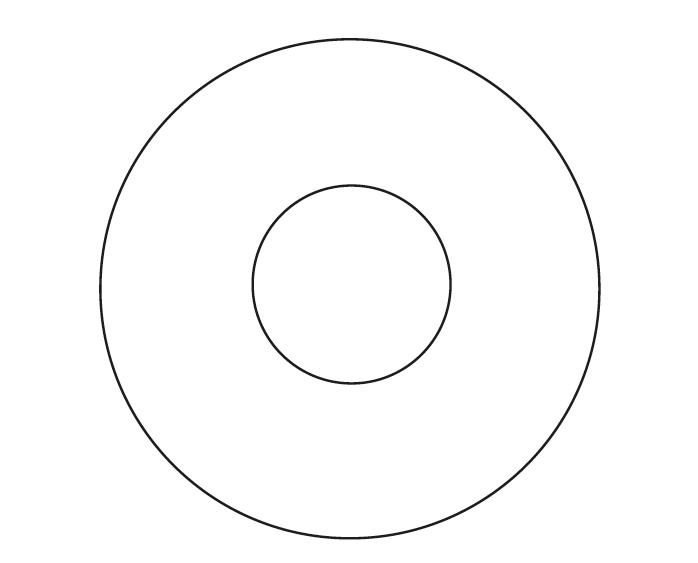

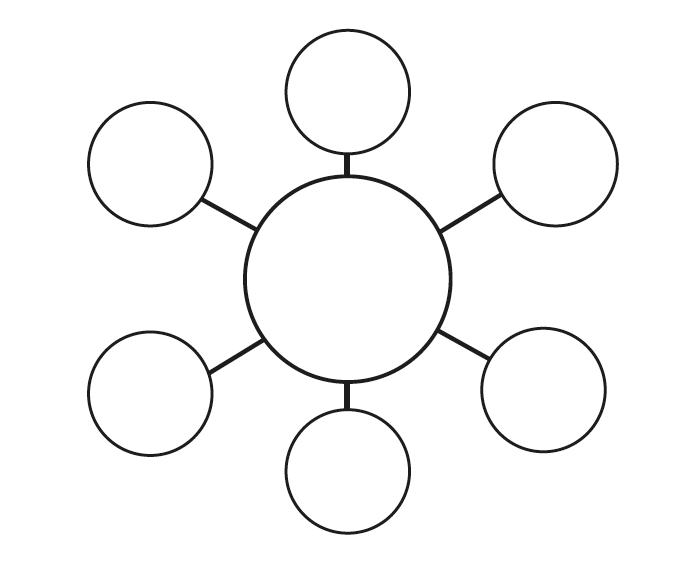

Circle map

Used for: Defining in context

For example: In the inner circle, write what you want to define – eg traditional tales. Then, in the outer larger circle, record in writing or pictures everything you know about this subject.

Bubble map

Used for: Describing

For example: In the middle circle, write or draw the person or object you are describing. Use the outer circles to record adjectives that describe the central person/object.

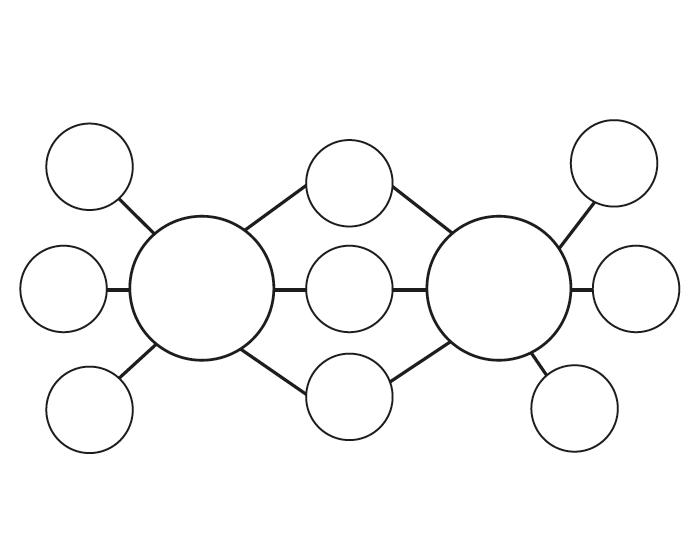

Double bubble map

Used for: Compare and contrast

For example: Write character names in the middle two circles. Use the circles that link to both for noting similarities. Use the circles linking to only one character to note differences.

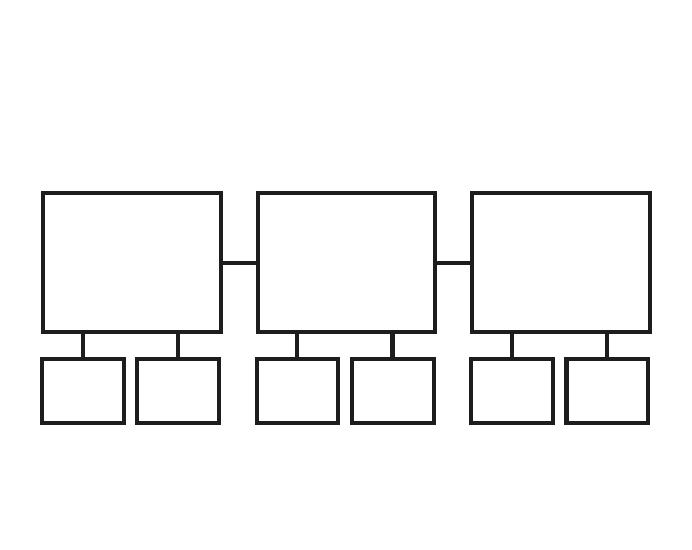

Flow map

Used for: Sequencing

For example: With a story, eg Little Red Riding Hood, use the main boxes to sequence what happens in that story. Use the smaller boxes to add additional information, such as describing how the characters are feeling.

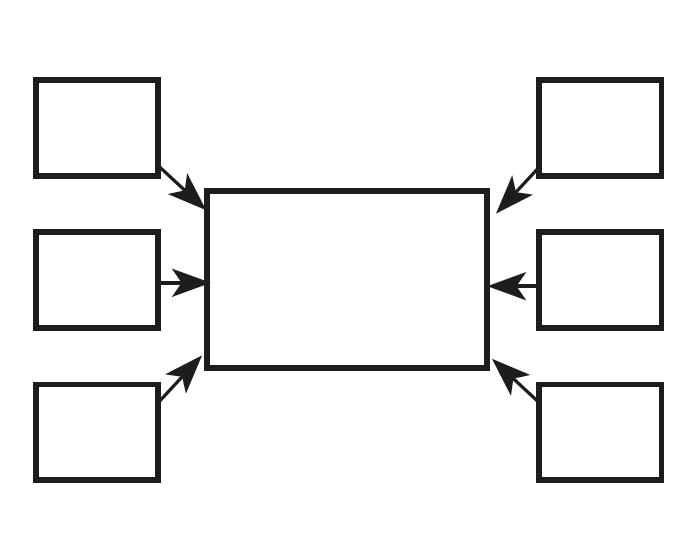

Multi-flow map

Used for: Cause and effect

For example: In Romeo and Juliet, use the map to identify the causes and effects of the different events in this story.

Tree map

Used for: Classifying

For example: Identifying different themes within a story.

Brace map

Used for: Whole parts

For example: Identifying the parts of a story (beginning, middle and end), then breaking down each part into further components, eg ‘what makes up the beginning of a story?’.

Bridge map

Used for: Seeing analogies

For example: Looking at the factor that links together villains in traditional tales.

The benefits of thinking maps as visual tools

Using the maps to support reading comprehension wasn’t well-established, but the potential was immediately obvious to East Sheen’s staff.

Year 6 teacher Carla Ruocco and literacy lead Debbie Canner set out to integrate thinking maps into reading lessons to examine the impact on children’s reading comprehension.

“As educators we are becoming more aware of the importance of children’s working memory,” says Carla.

“What we see is that as children become fluent with the use of thinking maps, they immediately know what type of thinking they require for the task at hand. That frees up more thinking capacity for the subject, rather than the process of recording.”

Debbie and Carla also extended the use of the maps by introducing colour coding. Each time the children revisited a map throughout a sequence of lessons, they used a different colour for recording.

In this way the children could demonstrate changes in thinking. When sharing their maps with other groups, the class or the teacher, children needed to explain and justify these changes.

Example teaching sequence with thinking maps

1 | Selecting the text

In this sequence, the teacher used a number of maps to support the children’s comprehension.

To begin, the children read a picture book for homework – Memorial, written by Gary Crew and illustrated by Shaun Tan.

This thought-provoking book about the impact of war on four generations of an Australian family generated some deep, reflective responses amongst the class

2 | Recording ideas and first responses

After reading, the children recorded their initial responses on a circle map. They noted their first impressions, any questions they had about the text and anything they found strange or puzzling.

The teacher used the completed maps to initiate discussion in a guided reading session. The children then shared these thoughts.

Debbie and Carla noted that there was far less teacher talk than usual. Rather than being fed a series of predetermined questions, the children were able to reflect more on their own responses and to make connections both with their own experiences, and with other texts.

The children listened attentively to each other’s ideas and raised their own questions as they were confronted with different ways of thinking about the text.

3 | Going deeper

Revisiting the text is an important part of the process. It allows children to build on the ideas that they have started to formulate, and to search for their own answers to any questions or confusions they might have.

There can be a tendency to move children quickly through one text to the next, but if we do, this we can lose opportunities for deeper learning.

The children reviewed the book page by page, moving on to the next page only once there was a general consensus that the group had fully explored their ideas.

The children studied the pictures and the text, noticing details that had passed them by on the first reading. The teacher encouraged them to add any new questions or thoughts to their circle maps.

By using a different colour pen, it was clear how the children’s understanding had developed from their initial ideas at home as a result of the guided session.

4 | Expanding thinking

When developing reading comprehension, the role of the teacher is to work with children’s current understandings – to prompt and pose questions that enable them to make connections.

You should probe their understanding and help them become more explicit about their ideas, as well as being able to justify them, and help develop their cognitive thinking processes.

To help deepen their understanding of the book, the children used a double bubble map to compare and contrast two symbols that are used in the story to represent remembrance – a statue and a tree.

They completed this together – again with very little teacher input – with the map helping to clearly organise their thoughts.

In making their points, the teacher asked them to give a well-reasoned response, even though their answers differed from each other.

At the end of the session, the teacher asked children to summarise their understanding of the story and review their circle maps to see if they had any unanswered questions.

This revealed that children’s comprehension had deepened further. It also served as an assessment to see where teachers could expand this in the following session.

5 | Comparing texts

In preparation for the next session the children read a short story, A World with No War, by David Almond. The school selected this as it has similar themes to Memorial.

Following a brief discussion in which children voiced their first impressions, Debbie and Carla presented the tree map for the children to record any themes that they identified.

“We were very impressed with how, in completing the map, the discussion was focused and channelled,” they said.

“The children were not only able to identify the themes and justify their thoughts, but they also recognised the similarities with Memorial and made other connections with other familiar texts, such as Romeo and Juliet.”

Results

In the process of using thinking maps to develop reading comprehension, the teachers noticed that discussions in class needed much less of their input, yet remained focused.

They also noticed that, on the few occasions they did intervene, they were able to offer more thoughtful input, which could take the children’s thinking to a deeper level.

Children who were already familiar with this process from other subjects also commented favourably, saying that the maps helped them explain their thinking about challenging texts.

They also said that it would enable them to learn more independently in their reading groups.

Books to use alongside thinking maps

If you want to implement thinking maps into your class, here are some great World War 1 stories that work perfectly with this method:

- The Silver Donkey by Sonya Hartnett (Walker Books)

- Line of Fire by Barroux and Sarah Ardizzone (Phoenix Yard)

- Memorial by Gary Crew and Shaun Tan (Hachette)

- A World with No War by David Almond in The Great War (Walker Books)

Nikki Gamble runs Just Imagine. For further information about Developing Excellence in Teaching Reading 7-14, contact [email protected].

Thinking maps heroes and villains KS2 lesson plan

Use thinking maps to explore both fictional and real-life goodies and baddies with this KS2 lesson plan from Russell Grigg and Helen Lewis…

‘Heroes and villains’ is an excellent topic to explore our rich and varied literary heritage, one of the aims of the English programme of study at KS2.

For this lesson plan, included in the download at the top of this page, Russell Grigg and Helen Lewis have drawn on the experiences of Sharon, a Y3 teacher at Deri View Primary in Abergavenny, who shows how she used a circle map, one of several thinking maps set out by academics Hyerle and Alper, to help children clarify their thinking about the topic and build a foundation for discussion and writing.

What they’ll learn

- Identify common characteristics of heroes and villains

- Clearly explain their ideas and where these come from

- Follow rules for classroom discussion; speaking, listening and responding to what people say