Although colonization was widespread in the late nineteenth century, Africa was still regarded as the “dark continent.” It was an untamed place of mystery and fear that most Europeans misunderstood. Railroad workers who were part of the effort to modernize Africa and bring contemporary transportation to the region would soon find that there was a reason to be afraid, as their nights would become consumed with horror by the actions of two lions, soon to be nicknamed The Ghost and The Darkness, leaving their mark on history as they embarked on their shocking killing spree.

“Modernizing” Tsavo

Tsavo, which today is the country’s largest national park, is a region of the country of Kenya in East Africa. In the late 1800s, the British Empire controlled this region and was working to bring infrastructure to the area in order to improve trade and, in turn, their income from their colonies. In 1898, a railroad project was underway in order to connect Uganda, the country west of Kenya, with the Indian Ocean to the east. This would greatly improve the movement of people and goods across the continent and help secure the empire’s hold on the region. The project was incredibly expensive but nevertheless persisted. Thousands of workers were required to make it a success.

Who Were the Workers…and Subsequent Victims?

The British Empire outlawed slavery in the early 1800s. However, this didn’t change the fact that they needed thousands of workers for their many imperial projects. As a result, many colonial subjects were “hired” under the guise of indentured servitude and forced into long periods of work in foreign countries. As a result of these efforts, thousands of Indian men and eventually women were brought to Africa throughout the 19th and into the 20th century to work. Many never returned home.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

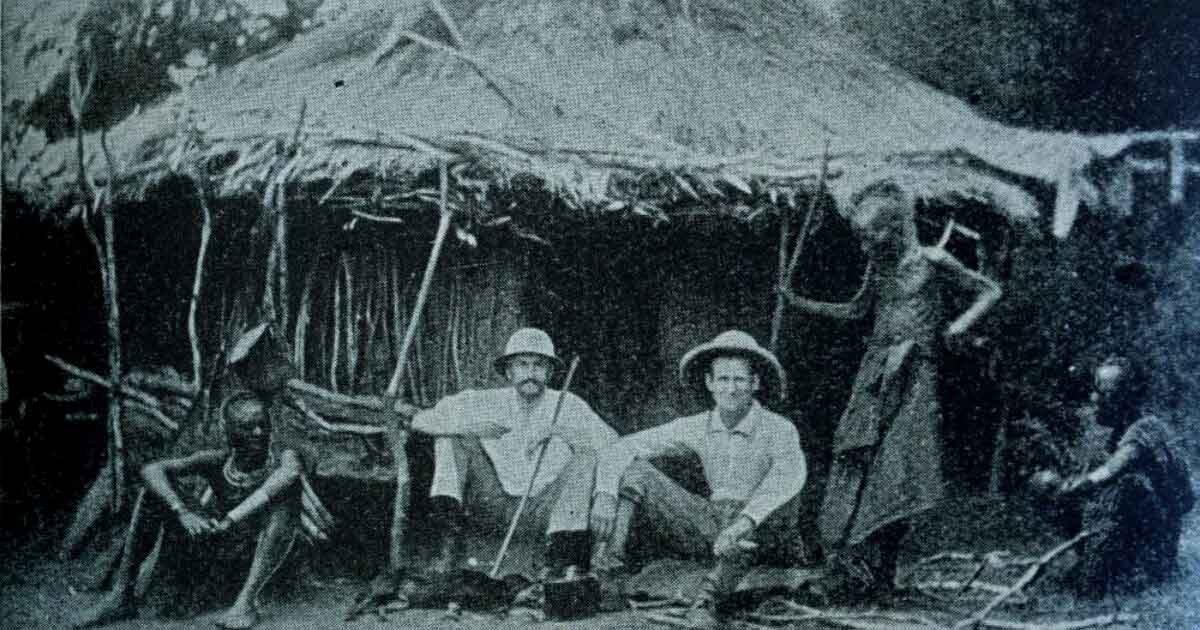

Sign up to our Free Weekly NewsletterIt was these Indian men (19,000 of them) who made up the majority of the workers on the railroad project, along with a few native Africans and British settlers rounding out the workforce. These men worked long hours and usually in poor conditions. Food rations were poor, with scurvy being commonplace. The men slept in tents. British workers were generally managers and overseers and had access to better food and shelter. As a result, the lion attacks fell along racial lines. Starting in early 1898, men began disappearing from their tents at night, often without a noise.

Calling in the Cavalry

In March of that year, Lt. Col. John Henry Patterson arrived in Tsavo. A civil engineer with a distinguished career in the British army, Patterson was there to ensure the success of the building project but soon became wrapped up in another goal-hunting the maneaters that were absconding with workers. Stories of disappearing men began crossing Patterson’s desk not long after his arrival and not long after the beasts were spotted. It was soon determined that two maneless male lions were responsible for the deaths. It sometimes seemed that a worker was killed every night. Since the workers’ tents were flimsy prevention against lion teeth and claws, some measures were taken to try and stop the attacks. Workers tended all-night bonfires and created thorn fences called bomas, but these did little to thwart the attackers. Some workers fled, and work on the railway stopped altogether at some points. Facing pressure from workers and the railway company, Patterson decided to go on the hunt.

Unique Biology

Those reading about the attacks across oceans and continents (and still today) may have been confused to read about male lions without their trademark manes. However, lions in the Tsavo region occupy a more arid climate than the typical African Serengeti lion. It is hotter and drier, and a mane would add unnecessary pressure to the lion’s everyday fight to survive. They’d lose water and energy in an attempt to stay cool. Without it, they are spared that waste and can focus their resources elsewhere. Tsavo lions also live in smaller prides than their Serengeti counterparts, with one male per 10 or so females. These two man-eaters were likely two single males without pride attachments.

On the Hunt

While Patterson was known as a skilled hunter and had a reputation for killing a tiger while in India, he was also not considered a marksman by any stretch. Attempts to trap the lions using goats and donkeys for bait failed, and they seemed to prefer human prey as they continued to pick off workers. Occasionally, the attacks would stop for brief periods, then resume again. Patterson gave the offenders nicknames that not only added to their mystery but embodied the stealth they used to whisk away their meals: The Ghost and The Darkness.

The End of the Killing Spree

Patterson began hunting the beasts by employing a variety of baits and sitting above the camp in a tree stand, both for safety and a better vantage point. One night in December, Patterson finally got a clean shot at one of the lions. Shooting twice, he managed to dispatch it. However, the other lion fled and was unharmed. The dead lion measured nine feet, eight inches from nose to the tip of his tail, and stood three foot nine at the shoulder, according to Patterson. Although its weight is unknown, it is said to have taken eight men to carry the lion. It was eventually skinned, and the skin displayed. As the news spread, Patterson received telegrams of congratulations from around the world. However, he knew the job wasn’t complete.

It took twenty days to catch up with the second lion. During that time, he returned to the railroad camp several times, though his only victims were goats. One night while on watch in a tree, Patterson spotted the lion stalking him and managed to get four shots off. He was fairly certain that at least two hit the lion, but it ran off anyway. Along with his gunbearer Mahina and a native tracker, Patterson followed the blood trail that the lion had left in its wake. They would find him not far from camp and fire many more bullets. After charging at least twice more, the lion would eventually succumb, falling about five feet away from Patterson, according to his own accounts. This lion was slightly longer and taller than his counterpart.

Patterson would have the two lions’ skins turned into rugs. Their skulls were also preserved. In 1924, he visited the Chicago Field Museum to give a talk and was persuaded to sell the relics to the museum. The skins were taxidermied to represent the lions as they had looked in life, though they were slightly smaller due to the shrinkage that occurred as a result of the rug-making process. The taxidermied mounts and skulls can be viewed in Chicago still today. Their residency at the museum has also allowed the lions to be studied further and for the public to learn more about potential causes for their bloodthirsty behavior.

Why Become Man-Eaters?

The question everyone wanted answered was why these lions turned to humans as their main source of nutrition. While the world may never know for certain what caused the attacks, several likely factors contributed to their onset. For centuries before the attacks, Arab caravans, whose main trade was in enslaved people, traveled through Tsavo on the way to ports such as Mombasa. The death rates on these trips were often high due to poor conditions and tropical diseases. The dead or dying were left where they lay, making for an easy meal for the local lions. It is possible that generations of lions learned that humans were a source of a tasty meal as a result. Studies have shown that human predation is a learned behavior that can be passed on to other lions. In addition, the year prior to the attacks had seen a sweeping epidemic of rinderpest, a disease that took out many ungulates, including domestic cattle and wild bison that comprise a good portion of the typical lion diet.

As a result, there were fewer food options for these lions. A third contributing factor may have been the dentition of the two lions. Later studies of the skulls indicated that at least one of the lions had dental disease and broken teeth, though the breakage may have been from Patterson’s shooting. However, if his teeth were broken previously, hunting may have been a challenge for him, leading him and his companion to seek out easy prey.

Media Frenzy

The world was eager to congratulate Lt. Col. Patterson on his success. The railroad project was back in business, and the men were willing to return to work. Patterson capitalized on this success by releasing an autobiographical novel about his hunt in 1907, entitled The Man-Eaters of Tsavo. The book has been through several editions and can still be found today in novel and e-book forms.

His fame was forever cemented, and he would go on to write several more books and serve with distinction in World War I. Patterson’s book would inspire three movies: Bwana Devil (1952), Killers of Kilimanjaro (1959), and most recently, The Ghost & The Darkness (1996). Although these movies all take artistic liberties with the story for even more drama, they take their basis from Patterson’s story.

Tsavo’s Man Eaters Today

No other lion has made an impact quite like the Tsavo lions in 1898. However, that doesn’t mean man-eaters have been absent from the Tsavo region. Lion-on-human attacks are not considered unusual in the Tsavo region, even in the modern era. Not only do the factors previously discussed potentially play an impact, but humans are encroaching on lion territory like never before. It is essential to not only remember history but to respect nature, even as the “mystery” of Africa has lessened.