On a steamy summer night in mid-July in the Meatpacking District, Brandon Boyd is coolly perched in a booth on the sixth floor of the Soho House fingering the array that lies on the table before him—heavy silver rings, endless strands of wooden beads, iPhones of varying size, and a stalagmite cluster of sweet potato fries. He is as thin as a monk, with long hair made light and coarse with Western exposure. A few grays sprout around his temples. He wears a white shirt with a sloping neckline and a fair amount of matte-finish jewelry. He’s dabbling in what looks like kale tabbouleh and sipping what is certainly filtered water.

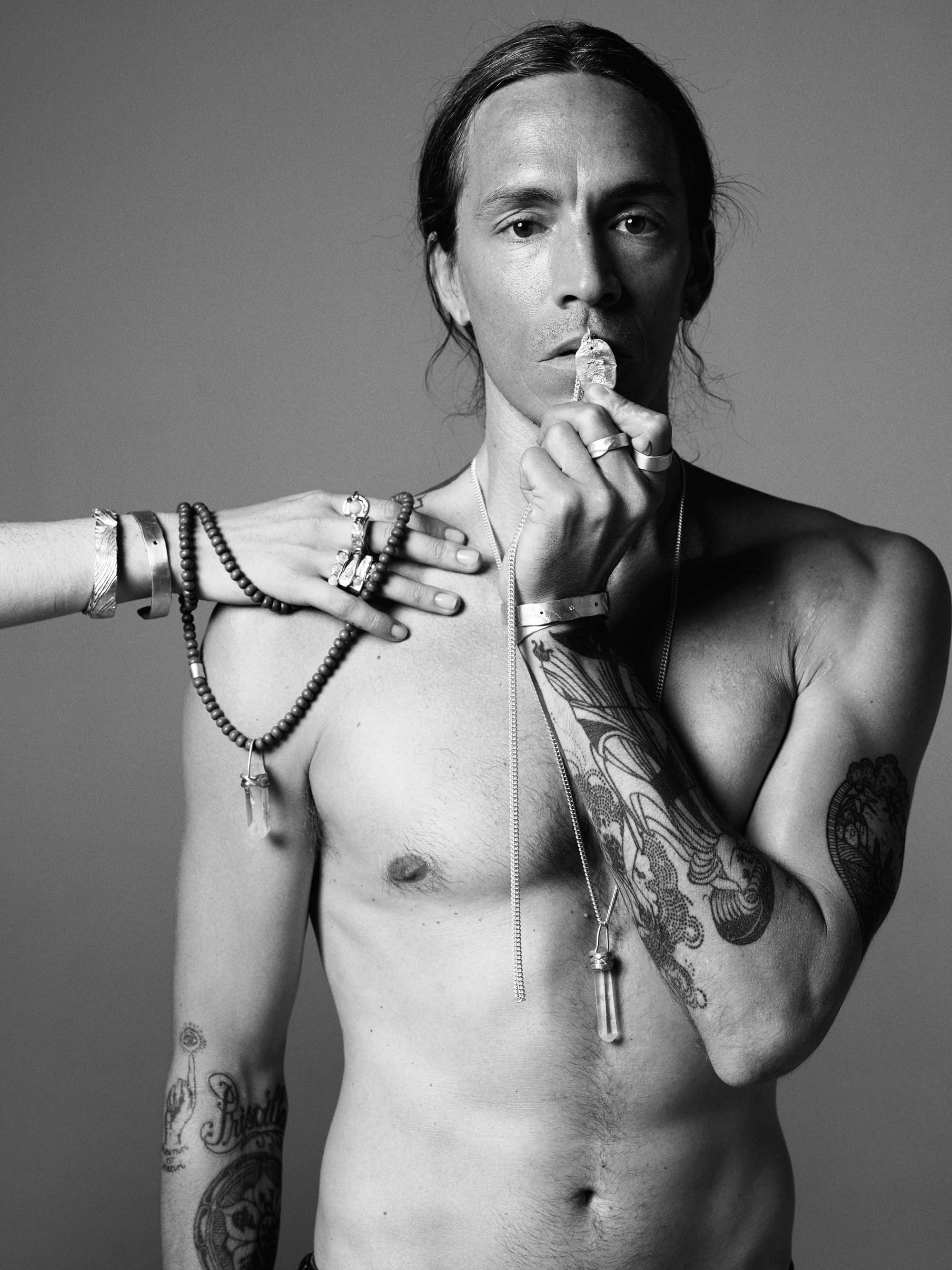

Treating your body as a temple and your mind as an altar is one of the more stable ways to approach enduring rock stardom. Boyd is, of course, the lead singer of Incubus, the ’90s darling of neo–alt rock known for, among other cultural coups, chart-smashing songs like “Drive,” the addition of a DJ to the traditional four-man-band schematic, and the incorrigible shirtlessness of their leading man. Not much has changed. Incubus is still alive, well, and touring; the members all seem to be enjoying their later acts (can’t say that for the Backstreet Boys). And Boyd, if Instagram is a reliable witness, is still frequently bereft of shirt. And in the tradition of professionals whose work uniform is primarily skin, like NBA players or construction workers, he’s plentifully and artfully tattooed, though perhaps with more sacred geometry than those other parties might go in for. To see him now, already a few fries in, he looks to be approaching that certain state of Zen reserved for people vaulted to fame in their youth, or death row inmates exonerated after years inside: There’s a sense of repentance through art, of “real world” weariness, of ageing with an E, of magick with a K.

For the past few months, Boyd has collaborated long-distance with New York–based jewelry designer Ali Grace on a collection that launches on her website today. Grace is a towering, sharp presence, with a keen eye for what’s tired and what’s still possible in the world of jewelry, a field where new designers are quick to be pigeonholed and novel designs even quicker to be ripped off. Her eponymous collections have presciently skittered along the edge of cool for the past few seasons—summer saw flowy gold boho, with lots of chains and pendants and feathers and leaves; fall shifted into the gear of a cross-country Harley, with a collection of silver rings and chokers that look like your angsty, gothy 13-year-old self rode into the sunset with your 13-year-old self’s idea of who Axl Rose was. Designs are hefty, with lines that look hand-formed and a shine and weight that feel expensive.

This new collaboration was a first for both parties. Grace previously kept her own artistic counsel, and Boyd had never made so much as a friendship bracelet. But the two established a cross-country system of exchange, capitalizing on Boyd’s visual-art skills—Grace would mail him strips of wax, Boyd would etch designs in them with a pencil, then mail them back for consideration and casting. This would eventually result in, among other things, a brass ring with undulating raised lines and an almond-shape clearing. “We call that the eye of God,” says Boyd. “It’s almost unconscious. I just draw and draw and draw and things just reappear over and over again.” One of the more successful pencil-in-wax operations, the ring is striking, hitting that artsy sweet spot of personal and transcendent. It’s something you’d be proud of yourself for finding in a shop or commune’s estate sale. It doesn’t look like a personal art project, but it does look deeply personal. That, too, was by design.

Boyd wasn’t just a consultant or “brand partner” in the operation—Grace used his own personal taste and affections as a compass and barometer for the collection, to a much higher than perfunctory degree. It was Boyd who ended up separating the sterling sheep from the goats. “Our through-line was, [Ali] kept saying, ‘Would you wear that?’ And I kept having that in my mind the further along we got—would I wear this?” Boyd simulated contemplation. “Hmm, yes, I would [gesticulating to the right]. This I wouldn't [and to the left]. And we kept tweaking.”

See also the strands of wood beads. They’re “mala beads” to the initiated; for Boyd, “some of the only necklaces I put around my neck.” Mala beads act as a sort of Zen rosary and abacus—there’s a certain perfect number, and each is handled and considered while a mantra is recited over it; repeat until you’ve polished off the strand. “For some reason, people have given them to me for most of my adult life, so I just have a lot of them,” says Boyd. “With mala beads, you’re not supposed to even wear them—you’re supposed to keep them in a pouch and take them out when you meditate. So ours are sort of ‘inspired-by,’ ” very much intended to be worn, as they are by both Grace and Boyd. The beads are a light, lovely sandalwood (fitting traditional specifications) and look like swirled amber pearls. Boyd received his current mantra through Transcendental Meditation (the kind David Lynch is trying to get all the kids into), though he’s somewhere between “forbidden” and “asked politely not” to tell anyone what it is. Vogue can confirm that it is indeed a single word, although your chances of guessing it don’t seem to improve from there. “It’s probably a nonsense word,” says Boyd.

Elsewhere in the collection are free-form and unscrupulously outlined heavy silver rings with tiny black diamonds notched in the top of the band. It’s a sort of moneyed-hippie answer to the fatuously macho screw marks on those old men’s Tiffany Metropolis bands. For Boyd, the stones are just glimmer enough. “I’ve always had a conflicted relationship with diamonds, because once you know where a lot of them come from, it’s hard to get your head around that,” says Boyd. “So Ali was able to source these beautiful ethically mined diamonds, which changed my mind about it a little. But at the same time, I wouldn’t want to wear things that jump off at you—nothing flashy. So Ali introduced the idea: What if we hid them?”

The other mainstay in enlightened coastal bliss—crystals—feature infrequently but impressively. There are several-inch-long pendants that drape from silver chains, soldered to a caging silver wire, and actually crystal clear. It’s not Boyd’s first encounter with the element. “Mostly I find them beautiful, but I’m sure there’s some kind of energetic quality that helps me think that they’re beautiful. I don’t know if they have healing powers, but they’re not hurting me—that I know of.” This casual take belies the fact that, in his California home, there are possibly hundreds of pounds of crystals, which he sources from Chile, Brazil, and in bulk from the Tucson Gem Show, where he bought “a master crystal—it’s five different kinds of crystals coming out of one stone,” says Boyd. “It takes like three people to move it.”

But there was something missing. Boyd’s famously gauged ears were once ne plus ultra, a model of the format. Now, across the table, his earlobes were limply unadorned. Does he still wear earrings, I asked? “Not really,” he said, turning to Grace, who mentioned they were a priority for the next collection. Boyd nodded assent. “We should make some for people who made bad decisions in the ’90s.”

.jpg)