In May 2014, Indians elected Narendra Modi’s opposition party into power. A political firebrand and a Hindu nationalist, Prime Minister Modi represents a significant change for the world’s largest democracy.

Who is Narendra Modi?

Narendra Modi became India’s prime minister in 2014, when his party won an historic landslide victory in the national general elections.

His rise is a big deal for India. Many Indians and members of the international business community like him because they see him as a CEO-style leader who can cut through India's notorious corruption and fix its economic slow-down.

His rise is a big deal for India. Many Indians and members of the international business community like him because they see him as a CEO-style leader who can cut through India's notorious corruption and fix its economic slow-down.

Modi’s rise also reflects a worrying trend of Hindu nationalism in India, and Modi himself has a record of stirring up Hindu-Muslim animosity. Fears about Modi’s record of creating religious tension were so high at the time of his election that The Economist published a cover story urging Indians to vote against him. “By refusing to put Muslim fears to rest, Mr. Modi feeds them. By clinging to the anti-Muslim vote, he nurtures it,” the magazine warned.

His political party, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), is popular among India’s urban middle and working classes. Like Modi, it’s known for Hindu nationalism and a pro-business orientation.

Since 2001, Modi has been the chief minister (roughly the Indian equivalent of an American governor) for Gujarat state, in India’s northwest. It has 60 million residents — one and a half times that of California — and has seen impressive economic growth under Modi’s tenure.

(Photo above: Modi at a 2009 rally, by SAM PANTHAKY/AFP/Getty.)

Why has Modi been so popular?

There are a few reasons. He and his party have a large support base among the urban middle and working classes, which are growingly rapidly. The party that had been in power for most of India’s history, the Congress Party, is increasingly seen as corrupt and inept. It presided over an economic slowdown and has no particularly inspiring political leaders. But the big issues are Modi’s record of economic growth and Hindu nationalism.

First: economic growth. Modi has been running India’s Gujarat state since 2001, during which time its economy has grown substantially. Many Indians support Modi because they believe he has a proven track record of economic success at a time when India’s overall growth is slowing, and that he can fight corruption and inefficiency in government. They have real grounds to believe that.

The other big reason for Modi’s popularity is Hindu nationalism. Yes, the thing that makes Modi so worrying is also what makes him so popular. Some significant chunk of BJP supporters really like Modi’s nationalism and want to see more of it. During his campaign, he didn’t just stir up religious tension and virulent nationalism because he likes those things personally; he was encouraged to do it by his popular support base.

Is there a funny video that explains Modi’s rise in a few minutes?

Yes! Former Daily Show correspondent John Oliver, in the inaugural episode of his new HBO comedy news program, did a segment explaining the Indian national election, including an overview of Narendra Modi’s superstar rise and the allegations that shadow him and his candidacy for prime minister.

In addition to being funny, it’s a pretty solid overview:

Oliver gives a good summary of the 2002 Gujarat violence and why that incident has so darkened Modi’s legacy. And Oliver’s bit on the hyper-shoutiness of Indian TV news is great and very, very true.

What is Hindu nationalism?

Hindu nationalism is a movement of right-wing nationalism and social conservatism combined with a Hindu political identity so strong that its ultimate effect has been described as, while not Hindu supremacy, then Hindu hegemony to the potential detriment of the 20 percent of Indians who are not Hindu. That often means Muslims.

Modi is an avowed Hindu nationalist. He’s been a member of a Hindu nationalist group, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (or RSS), since the 1970s, and the group has endorsed him for prime minister. The RSS had been previously banned for violence. It has since moderated, but the point is that one reason people worry about Hindu nationalism is its history of extremism. Today, though, that doesn’t come out in direct acts of violence so much as in rhetoric that stirs up religious resentment, which itself can lead to bloodshed.

Modi’s reputation for Hindu nationalism comes primarily from his speeches (more on that here) and a 2002 spate of religious violence that occurred in the state he ran before becoming prime minister (more on that here).

Religious or ethnic nationalist movements tend to be dangerous anywhere, but this is particularly the case in India, which has a complicated history of Hindu-Muslim tension and violence that, while far better than it was in the past, can occasionally return.

Why is there religious violence in India?

India’s constitution declares the country to be secular and there is a tradition of celebrating and embracing religious diversity. However, India’s history is also marred by clashes between people of different religious backgrounds — particularly Hindus and Muslims. Modi is at the tip of a rising movement of Hindu nationalism that has exacerbated this tension in the past.

The thing you have to understand about India is the devastating pattern of Hindu-Muslim violence that has recurred since 1947, when the partition and independence of the British Raj created the nations of Pakistan and India. About 10 million people who lived on either side of the divide relocated to the country of their religion. Over one million people died in religious violence during the partition and a Hindu-Muslim wound opened that has not yet healed. That bit of history alone could never fully explain something as complex as religious violence, but it’s an important piece of it.

Many Muslims did remain in India after 1947, and on the vast majority of days and in the vast majority of cities there is no violence between Hindus and Muslims who live side by side. However, there can be fear and mistrust on both sides that has at times led to violence, often precipitated by growing religious tensions. One of the deadliest incidents since 1947 occurred in Gujarat state in 2002, which Modi was leading at the time. The legacy of that incident, and Modi’s possible links to it, hung over him during the election.

Why are people worried about Modi stoking religious violence?

Modi’s Hindu nationalist rhetoric during and before the election was a significant part of his rise, and while to India’s many Hindu nationalists this looks like the correct and exciting glorification of Indian Hindus, to much of the rest of the world it looks like ginning up religious tension and religious chauvinism. Modi has appeared to have moderated this rhetoric since taking office.

Religious nationalism only makes sense when there is another religion or out-group to hold yourself up against. For Hindu nationalists and Modi in particular, this often means Muslims. He's accused political opponents of being "Pakistani agents" and implied that Muslims were enemies of the state, for example.

The incident for which he receives by far the most criticism is a spate of anti-Muslim violence in his state of Gujarat in 2002 (more on that here), which came shortly after Modi and BJP’s rise in the state on Hindu nationalist rhetoric, and which Modi’s government did suspiciously little to stop.

This is not all in the past. While Modi has scaled back the rhetoric that’s drawn so much criticism in the past, there were still flashes of it during the election — perhaps in part because he needs Hindu nationalists’ votes. For example, he’s made speeches condemning India’s beef export industry. This may sound innocuous, but within India it’s a clear dogwhistle aimed at the Indian Muslims who dominate the beef industry, and meant to stir up Hindus who find beef consumption religiously objectionable. As the Financial Times pointed out, it’s not so different from the kind of rhetoric that has led to communal violence in the past.

Also during the election, a video surfaced showing Modi’s top lieutenant at a private election gathering in a part of India that has seen recent Hindu-Muslim violence. He told the Hindus gathered that voting for Modi would lead to “honor and revenge” for the killings.

“This is the time to avenge,” he said. It’s a bit like Mitt Romney’s 47 percent video, except instead of belittling welfare recipients the Indian official appeared to be hinting at the need for religious reprisal killings.

Fortunately, Modi’s actions as prime minister have not confirmed the worst fears of outside observers; he has not indulged such rhetoric while in office. That’s a good development. Still, it remains a worrying possibility that many analysts are keeping a wary eye on.

What was the 2002 Gujarat violence that has so marred Modi’s image?

Gujarat is a state in northwest India of about 60 million people. Modi became its political chief in 2001. The next year, deadly religious violence broke out. Accusations have ever since hung over Modi that his rhetoric had stirred up religious tension, that his government allowed the killing, and that it may have even abetted the violence.

The incident began when a group of Muslims set a train full of Hindus on fire, killing 59. In response, mass Hindu riots broke out against Muslim communities, killing an estimated 1,200 people, mostly Muslims, over three days of rapes and killings, often by immolation. Many reports indicated that the police of Gujarat state did nothing to stop the attacking mobs, and Modi and his government have long been accused of allowing, and potentially abetting, the riots.

This is not a fringe conspiracy theory: the US State Department denied Modi a visa to visit the US in 2005 over his suspected role in the incident.

A few months after the riots, New York Times reporter Celia Dugger asked Modi if he wished he handled the riots any differently. He told her his greatest regret was not handling the media better. Dugger said in a Times video interview that Modi did not show “any regret or [express] any empathy for those who had been slaughtered in his state, on his watch.”

That lack of concern has been an apparent factor throughout his career, and his lack of visible remorse or apology has contributed to the larger narrative of Modi as someone who is untroubled by anti-Muslim violence or by the effects of Hindu nationalist political rhetoric.

Can Modi fix India’s economy?

Lots of Indians, as well as members of the international business community, think Modi’s background as Gujarat’s leader make him qualified to fix India’s economic woes, and he’s styled himself as India’s national CEO. Optimism about a BJP powered the Indian stock market to new highs in spring 2014.

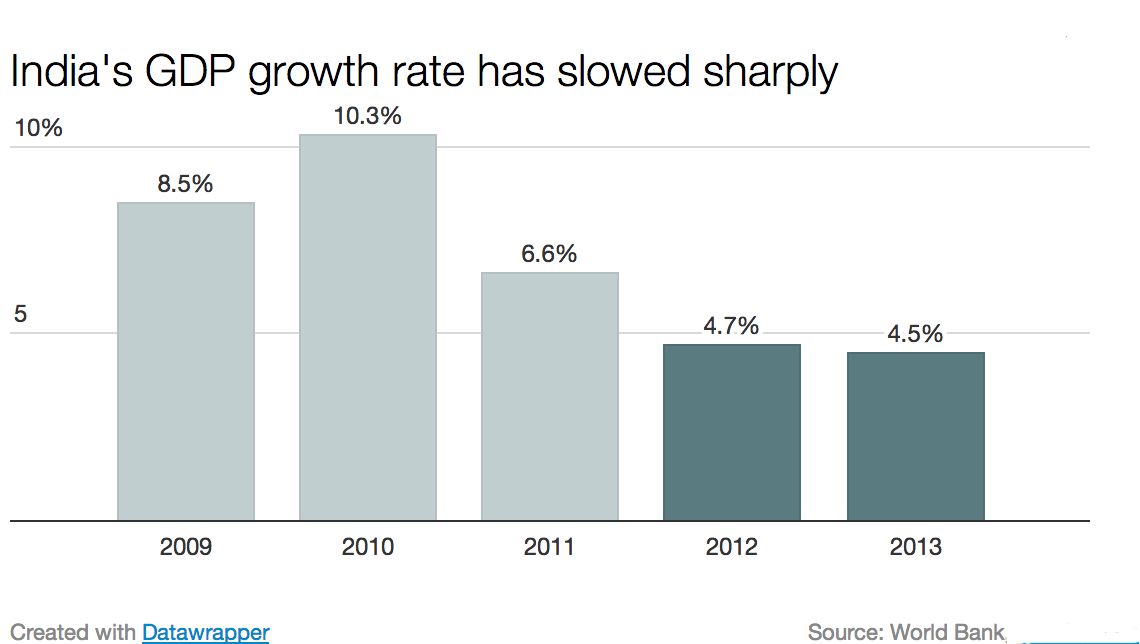

India’s economy was not doing great in the years before the 2014 election:

There’s a lot of demand in the Indian economy, but not enough supply, and India’s poor infrastructure and weak governance have been unable to provide the needed increase in production of goods and services. That’s meant higher prices — inflation — without enough growth.

Modi’s supporters believe he’ll be able to fix this by implementing cleaner governance, by cutting down on the corruption and bureaucracy that prevents businesses from growing, and by improving infrastructure so that business can sell more products domestically and abroad.

It’s tough to say whether Modi would be successful. The stated economic platforms of his party and the now out-of-power Congress Party are not particularly distinct, particularly on corruption and infrastructure. Still, Congress was in power for a while so it tends to take the blame for the status quo. Many Indians believed Congress had failed and that it was time for a change.

The big question, then, is whether Modi would be able to reproduce his reputation as an economic miracle worker from his time running Gujarat state. The numbers are impressive, but some analysts argue not nearly as impressive as Modi presents them to be.

— Matthew Yglesias

Why did Modi keep his wife a secret for nearly 50 years?

In mid-April of 2014, a few days into India’s six-week-long election, Modi revealed that he has been married for the previous 45 years. Yes, this was news: the 63-year-old had long presented himself as a bachelor.

The reason that matters is that Modi is a member of a Hindu nationalist group called RSS, which is thought to require a vow of celibacy. Modi eventually transitioned from the RSS to his political party, the BJP, and became a big-deal politician. He’s been apparently unmarried throughout his public life and touted this as a virtue (he argues that lacking a family gives him less of an incentive for corruption). It fits well with his image as a clean-cut, all-business political leader — not to mention as a right-leaning religious conservative.

The official story of what happened is that Modi’s family arranged the marriage when he was 18 and his wife, Jashodaben Chimanlal Modi, was 17. They reportedly spent only three months together over a period of three years, he left, and they’ve been legally married but functionally separated ever since. Jashodaben is a retired teacher and says she bears no ill will.