Top Qs

Timeline

Chat

Perspective

Political philosophy

Study of the foundations of politics From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Remove ads

Remove ads

Political philosophy studies the theoretical and conceptual foundations of politics. It examines the nature, scope, and legitimacy of political institutions, such as states. This field investigates different forms of government, ranging from democracy to authoritarianism, and the values guiding political action, like justice, equality, and liberty. As a normative field, political philosophy focuses on desirable norms and values, in contrast to political science, which emphasizes empirical description.

Political ideologies are systems of ideas and principles outlining how society should work. Anarchism rejects the coercive power of centralized governments. It proposes a stateless society to promote liberty and equality. Conservatism seeks to preserve traditional institutions and practices. It is skeptical of the human ability to radically reform society, arguing that drastic changes can destroy the wisdom of past generations. Liberals advocate for individual rights and liberties, the rule of law, private property, and tolerance. They believe that governments should protect these values to enable individuals to pursue personal goals without external interference. Socialism emphasizes collective ownership and equal distribution of basic goods. It seeks to overcome sources of inequality, including private ownership of the means of production, class systems, and hereditary privileges. Other schools of political thought include environmentalism, realism, idealism, consequentialism, perfectionism, individualism, and communitarianism.

Political philosophers rely on various methods to justify and criticize knowledge claims. Particularists use a bottom-up approach and systematize individual judgments, whereas foundationalists employ a top-down approach and construct comprehensive systems from a small number of basic principles. One foundationalist approach uses theories about human nature as the basis for political ideologies. Universalists assert that basic moral and political principles apply equally to every culture, a view rejected by cultural relativists.

Political philosophy has its roots in antiquity, such as the theories of Plato and Aristotle in ancient Greek philosophy. Confucianism, Taoism, and legalism emerged in ancient Chinese philosophy while Hindu and Buddhist political thought developed in ancient India. Political philosophy in the medieval period was characterized by the interplay between ancient Greek thought and religion in both the Christian and Islamic worlds. The modern period marked a shift towards secularism as diverse schools of thought developed, such as social contract theory, liberalism, conservatism, utilitarianism, Marxism, and anarchism.

Remove ads

Definition and related fields

Summarize

Perspective

Political philosophy is the branch of philosophy studying the theoretical and conceptual foundations of politics. It considers the relation between individual and society, the best organization of collective life, the distribution of goods and power, the limits of state authority, and the values guiding political decisions. This field examines basic concepts like state, government, power, legitimacy, political obligation, justice, equality, and liberty, analyzing their essential features and how they influence citizens, communities, and policies.[1] Schools of political philosophy, such as liberalism, conservatism, socialism, and anarchism, offer diverse interpretations of these concepts. They are guided by different values and propose distinct frameworks for structuring societies.[2] As a systematic and critical inquiry, political philosophy scrutinizes established beliefs and explores alternative views.[3] A central motivation for this investigation is that forms of government are not predetermined facts of nature but human creations that can be actively shaped to the benefit or detriment of some or all.[4]

Political philosophers address various evaluative or normative issues. They examine ideal forms of government and describe the values and norms that should guide political decisions.[5] They differ in this regard from political scientists, who focus on empirical descriptions of how governments and other political institutions actually work rather than how they ideally should work.[6] The term political theory is sometimes used as a synonym of political philosophy, but some interpreters distinguish the two. According to this view, political philosophy seeks to answer general and fundamental questions, whereas political theory analyzes and compares more specific aspects of political institutions while being more closely associated to the sciences.[7]

Political philosophy has its roots in ethics—the area of philosophy studying moral phenomena—and is sometimes considered a branch of ethics.[a] While ethics examines right conduct and the good life in the broadest sense, political philosophy has a more narrow scope, focusing on the political domain.[9][b] Political philosophy is also closely related to social philosophy and philosophical treatises often discuss the two together without clearly distinguishing between them. Despite their overlap, one difference between the two is that social philosophy examines diverse kinds of social phenomena while political philosophy has a more specific focus on power and governance.[10] Other connected fields include the philosophy of law and economics.[11]

The term political philosophy has its roots in the ancient Greek words Πολιτικά (politiká, meaning 'affair of the state') and φιλοσοφία (philosophía, meaning 'love of wisdom').[12] It is one of the oldest branches of philosophy and has been practiced in many different cultures.[13]

Purpose

In the Oxford Handbook of Political Theory (2009), the field is described as: "an interdisciplinary endeavor whose center of gravity lies at the humanities end of the happily still undisciplined discipline of political science ... For a long time, the challenge for the identity of political theory has been how to position itself productively in three sorts of location: in relation to the academic disciplines of political science, history, and philosophy; between the world of politics and the more abstract, ruminative register of theory; between canonical political theory and the newer resources (such as feminist and critical theory, discourse analysis, film and film theory, popular and political culture, mass media studies, neuroscience, environmental studies, behavioral science, and economics) on which political theorists increasingly draw."[14][excessive quote]

In a 1956 American Political Science Review report authored by Harry Eckstein, political philosophy as a discipline had utility in two ways:

the utility of political philosophy might be found either in the intrinsic ability of the best of past political thought to sharpen the wits of contemporary political thinkers, much as any difficult intellectual exercise sharpens the mind and deepens the imagination, or in the ability of political philosophy to serve as a thought-saving device by providing the political scientist with a rich source of concepts, models, insights, theories, and methods.[15]

In his 2001 book A Student's Guide to Political Philosophy, Harvey Mansfield contrasts political philosophy with political science. He argues that political science "apes" the natural sciences and is a rival to political philosophy, replacing normative words like "good", "just", and "noble" with words like "utility" or "preferences". According to Mansfield, political science rebelled from political philosophy in the seventeenth century and declared itself distinct and separate in the positivist movement of the late nineteenth century. He writes:

"Today political science is often said to be 'descriptive' or 'empirical,' concerned with facts; political philosophy is called 'normative' because it expresses values. But these terms merely repeat in more abstract form the difference between political science, which seeks agreement, and political philosophy, which seeks the best."

According to Mansfield, political science and political philosophy are two distinct kinds of political philosophy, one modern and the other ancient. He stresses that the only way to understand modern political science and its ancient alternative fully is to enter the history of political philosophy and to study the tradition handed down over the centuries. Although modern political science feels no obligation to look at its roots, and might even denigrate the subject as if it could not be of any real significance, he says, "our reasoning shows that the history of political philosophy is required for understanding its substance".

Remove ads

Basic concepts

Summarize

Perspective

Political philosophers rely on various basic concepts to formulate theories and conceptualize the field of politics. Politics encompasses diverse activities associated with governance, collective decision-making, reconciliation of conflicting interests, and exercise of power. Some theorists characterize it as the art of skillfully engaging in these activities.[16]

Government, power, and laws

The state, a fundamental concept in political philosophy, is an organized political entity. States are associations of people, called citizens. They typically exercise control over a specific territory, implement the rule of law, and function as juristic persons subject to rights and obligations while engaging with other states. However, the precise definition of statehood is disputed. Some philosophical characterizations emphasize the state's monopoly on violence and the subordination of the will of the many to the will of a dominant few. Another outlook sees the state as a social contract for mutual benefit and security. States are characterized by their level of organization and the power they wield, in contrast to stateless societies, which are more loosely ordered social groups connected through a less centralized web of relationships. Nation, a related concept, refers to a group of people with a common identity based on shared culture, history, or language. Many states today are nation-states, meaning that their citizens share a common national identity that aligns with the state's political boundaries. Historically, the first states in antiquity were city-states.[17]

A government is an institution that exercises control and governs the people belonging to a political entity, usually a state. Some political philosophers see the government as an end in itself, while others consider it a means to other goods, such as peace and prosperity. Some governments set down fundamental principles, called constitution, that outline the structure, functions, and limitations of governmental authority, while others exercise unconstrained authority. Anarchists reject governments and advocate self-governance without a centralized authority.[18]

Political philosophers distinguish various forms of government based on who wields political power and how it is wielded. In democracies, the main power lies with the people. In direct democracies, citizens vote directly on laws and policies, whereas in indirect democracies, they elect leaders who make these decisions. Democracies contrast with authoritarian regimes, which reject political plurality and suppress dissent through centralized, hierarchical power structures. In the case of autocracies, absolute power is vested in a single person, such as a monarch or a dictator. For oligarchies, power is concentrated in the hands of a few, typically the wealthy. An authoritarian regime is totalitarian if it seeks extensive control over public and private life, such as fascism, which combines totalitarianism with nationalist and militarist political ideologies.[19]

Aristocracy, another form of government, implements rule by the elites, such as a privileged ruling class or nobility.[20] In the case of meritocracies, the ruling elites are chosen by skill rather than social background.[21] For technocracies, people with technical skills, such as engineers and scientists, wield political power.[22] Theocracies prioritize religious authority in political decision-making, implement religious laws, and claim legitimacy by following the divine will.[23] Political philosophers further discuss federalism and confederalism, which are systems of governance involving multiple levels: in addition to a central national government, there are several regional governments with distinct responsibilities and powers. These systems contrast with colonialism, where occupied territories are exploited rather than treated as equal partners, and with unitary states, where authority is centralized at the national level.[24]

A key aspect of governments and other political institutions is the power they wield. Power is the ability to produce intended effects or control what people and institutions do. It can be based on consent, like people following a charismatic leader, but can also take the form of coercion, such as a tyrannical ruler enforcing compliance through fear and repression.[25] The powers of government typically include the legislative power to establish new laws or revoke existing ones, the executive power to enforce laws, and the judicial power to arbitrate legal disputes. Governments following the separation of powers have distinct branches for each function to prevent overconcentration and abuse of power.[26] Language is a central aspect of political power, serving as a medium of communication and a force shaping public opinion. Linguistic power dynamics are reflected in the control of the means of communication, such as mass media, and in the freedom of speech of each individual.[27]

Legitimacy, another fundamental concept, is the rightful or justified use of power. Political philosophers examine whether, why, and under what conditions the powers exercised by a government are legitimate. Often-discussed requirements include that power is acquired following established rules and used for rightful ends.[28] For instance, the rules of representative democracies assert that elections determine who acquires power as the legitimate ruler. Authority, a closely related concept, is the right to rule or the common belief that someone is legitimized to exercise power. In some cases, a person may have authority even if they lack the effective power to act. Some theorists also talk of illegitimate authority in situations where the common belief in the legitimacy of a use of power is mistaken.[29]

Governments typically use laws to wield power. Laws are rules of social conduct that describe how people and institutions may or may not act. According to natural law theory, laws are or should be expressions of universal moral principles inherent in human nature. This view contrasts with legal positivism, which sees laws as human conventions.[30] Political obligation is the duty of citizens to follow the laws of their political community. Political philosophers examine in what sense citizens are subject to political obligations even if they did not explicitly consent to them. Political obligation may or may not align with moral obligation—the duty to follow moral principles. For example, if an authoritarian state imposes laws that violate basic human rights, citizens may have a moral obligation to disobey.[31]

Laws governing property are foundational to many legal systems. Property is the right to control a good, including the rights to use, consume, lend, sell, and destroy it. It covers both material goods, like natural resources, and immaterial goods, such as copyrights associated with intellectual property. Public property pertains to the state or community, whereas private property belongs to other entities, such as individual citizens. Various discussions in political philosophy address the advantages and disadvantages of private property.[32] For example, communism seeks to abolish most forms of private property in favor of collective ownership to promote economic equality.[33]

Justice, equality, and liberty

Diverse concepts in political philosophy act as values or goals of political processes.[35] Justice is a complex concept at the core of many political concerns. It is specifically associated with the idea that people should be treated fairly and receive what they deserve. More broadly, it also refers to appropriate behavior and moral conduct, but its exact meaning varies by context: it can be an aspect of actions, a virtue of actors, or a structural feature of social situations. In the context of social life, social justice encompasses various aspects of fairness and equality in regard to wealth, assets, and other advantages. It includes the idea of distributive justice, which promotes an impartial allocation of resources, goods, and opportunities. In legal contexts, retributive justice deals with punishment, with one principle being that the harm inflicted on an offender is proportional to their crime.[36]

Justice is closely related to equality, the ideal that individuals should have the same rights, opportunities, or resources. Equality before the law is the principle that all individuals are subject to the same legal standards, rights, and obligations. Political equality concerns the abilities to vote for someone and to become a candidate for a political position. Equal opportunity is the ideal that everyone should have the same chances in life, meaning that success should be based on merit rather than circumstances of birth or social class. This contrasts with equality of outcome, the idea that all people should have similar levels of material wealth and living standards. Philosophers of politics examine and compare different conceptions of equality, discussing which of its aspects should guide political action. They also consider the influence of discrimination, which refers to unfair treatment based on race, gender, sexuality, and class that can undermine equality. The school of political thought known as egalitarianism sees equality as one of the main goals of political action.[37]

Liberty or freedom[c] is the ideal that people may act according to their will without oppressive restrictions. Political philosophers typically distinguish two complementary aspects of liberty: positive liberty—the power to act in a certain way—and negative liberty—the absence of obstacles or interference from others. Liberty is a key value of liberalism, a school of political philosophy.[39] Competing schools of thought debate whether laws necessarily limit liberty by restricting individual actions to protect the common good or enable it by creating a safe framework in which individuals can exercise their rights freely.[40] Liberty as an ability to do something is sometimes distinguished from license, which involves explicit permission to do something.[41] Autonomy, another closely related concept, is the ability to make informed decisions and govern oneself by being one's own master.[42]

Welfare, well-being, and happiness express the general quality of life of an individual and are central standards for evaluating policies and political institutions. Some philosophers understand these phenomena as subjective experiences, linked to the presence of pleasant feelings, the absence of unpleasant ones, and a positive self-assessment of one's life. Others propose an objective interpretation, arguing that the relevant factors can be objectively measured, such as economic prosperity, health, education, and security. Various schools of political thought, such as utilitarianism and welfarism, see happiness or well-being as the ultimate goal of political actions.[43] Welfare states are states that prioritize the social and economic well-being of their citizens through measures such as affordable healthcare systems, social security, and free access to education for all.[44]

Remove ads

Major schools of thought

Summarize

Perspective

Anarchism

Anarchism is a school of political thought[d] that rejects hierarchical systems, arguing for self-governing social structures and a stateless society, known as anarchy. Anarchists typically see liberty and equality as their guiding values. They understand authority over others as a threat to individual autonomy and criticize hierarchical structures for perpetuating power imbalances and inequalities. As a result, they challenge the legitimacy of centralized governments wielding coercive power over others.[e] Anarchism maintains that freedom from domination is central to human flourishing. It promotes social structures based on voluntary association to advance universal egalitarianism.[48]

Various schools of anarchism have been proposed.[49] Absolute or a priori anarchism rejects any form of state, arguing that state power is inherently illegitimate and unjust. Contingent or a posteriori anarchism presents a less radical view, suggesting that states are not inherently bad but nonetheless usually fail in practice. For example, utilitarian anarchists reject states based on the claim that they typically do not promote the greatest good for the greatest number of people because their disadvantages outweigh their advantages.[46] Individualist anarchists emphasize the importance of individual freedom, seeking to defend it against any social structure that restricts personal autonomy, including parental authority and legal institutions. This outlook can take the form of libertarian anarchism or anarcho-capitalism. Collectivist or socialist anarchists, by contrast, stress the importance of community and voluntary cooperation within society, advocating collective ownership of resources and the means of production. For example, anarchist communism argues for decentralized social organization and communal sharing to promote well-being for all.[50]

Diverse criticisms of anarchism have been articulated. Some see anarchism as primarily a negative attitude that seeks to destroy established institutions without providing viable alternatives, thereby simply replacing order with chaos. Another objection holds that anarchy is inherently unstable since hierarchical structures emerge naturally, meaning that stateless societies will inevitably evolve back into some form of state. Further arguments assert that the guiding anarchist goal is based on an unreachable utopian ideal and that anarchism is incoherent since the attempt to undermine all forms of authority paradoxically is itself a new form of authority.[51]

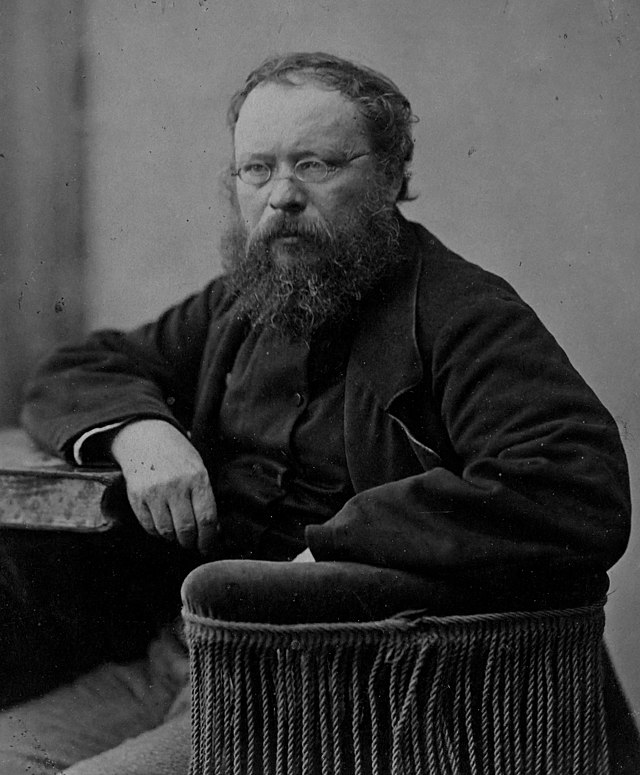

There are several prominent anarchist thinkers, representing different schools of thought. Pierre-Joseph Proudhon is commonly considered the father of modern anarchism, specifically mutualism. Peter Kropotkin is another classic anarchist thinker, who was the most influential theorist of anarcho-communism. Mikhail Bakunin's specific version of anarchism is called collectivist anarchism. Max Stirner was the main representative of the anarchist current known as individualist anarchism and the founder of ethical egoism which endorses anarchy.[52] Henry David Thoreau was an influential anarchist thinker writing on topics such as pacifism, environmentalism and civil disobedience. Noam Chomsky is a leading critic of U.S. foreign policy, neoliberalism and contemporary state capitalism, the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, and mainstream news media, influential in the anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist movements and aligned with anarcho-syndicalism and libertarian socialism.[53][54][55]

Conservatism

Conservatism is a school of political thought that seeks to preserve and promote traditional institutions and practices. It is typically driven by skepticism about the human ability to radically reconceive and reform society, arguing that such attempts, guided by a limited understanding of the consequences, often result in more harm than good. Conservatives give more weight to the wisdom of historical experience than the abstract ideals of reason. They assert that since established institutions and practices have passed the test of time, they serve as foundations of stability and continuity. Despite its preference for the status quo, conservatism is not opposed to political and social change in general but advocates for a cautious approach. It maintains that change should happen as a gradual and natural evolution rather than through radical reform to ensure that political arrangements deemed valuable are preserved.[57]

While the exact institutions and practices to be preserved depend on the specific cultural and historical context of a society, conservatives generally emphasize the importance of family, religion, and national identity. They tend to support private property as a safeguard against state power and some forms of social security for the poor to maintain societal stability.[58]

Distinct strands of conservative thought follow different but overlapping approaches. Authoritarian conservatism prioritizes centralized, established authorities over the judgment of individuals. Traditionalist conservatism sees general customs, conventions, and traditions as the guiding principles that inform both established institutions and individual judgments. Romantic or reactionary conservatism is driven by nostalgia and seeks to restore an earlier state of society deemed superior. Other discussed types include paternalistic conservatism, which argues that those in power should care for the less privileged, and liberal conservatism, which includes the emphasis on individual liberties and economic freedoms in the conservative agenda.[59]

Different criticisms of conservatism have been proposed. Some focus on its resistance to change and lack of innovation, arguing that the prioritization of the status quo perpetuates existing problems and stifles progress. In particular, this concerns situations in which rapidly evolving societal challenges require dynamic, flexible, and creative responses. Another objection targets conservative skepticism about the capacity of reason to effectively address complex social issues, arguing that this skepticism is exaggerated and hinders well-thought-out reforms and meaningful improvements. Some critics state that conservatism reinforces established social hierarchies and inequalities, benefiting primarily privileged social classes.[60]

There have been a number of influential conservative philosophers. Edmund Burke, widely considered the father of conservatism, published Reflections on the Revolution in France in which he denounced the French Revolution, although he supported the American Revolution.[61] An exponent of liberal conservatism, French sociologist Alexis de Tocqueville is known for his works Democracy in America and The Old Regime and the Revolution. A German political theorist of the Conservative Revolution movement, Carl Schmitt developed the concepts of the friend/enemy distinction, the state of exception, and political theology. Leo Strauss famously rejected modernity, mostly on the grounds of what he perceived to be modern political philosophy's excessive self-sufficiency of reason and flawed philosophical grounds for moral and political normativity, arguing instead that we should return to pre-modern thinkers for answers to contemporary issues. Julius Evola, an exponent of reactionary traditionalism, called for a return to pre-Renaissance values of tradition and aristocracy while discussing possible ways to survive the inevitable collapse of modern civilization and to bring forth a new order.

Liberalism

Liberalism is a philosophical tradition emphasizing individual liberties and rights, the rule of law, tolerance, and constitutional democracy. It encompasses a variety of ideas without a precise definition. Some liberals follow John Locke's view that all individuals are born free and equal, highlighting the government's role in protecting this natural state. Others associate liberalism more with the individual's ability to participate in democratic institutions than with equality. Central commitments for most liberals are support of various forms of liberty, such as freedom of speech, freedom of religion, and free choice of profession. Liberalism allows for diverse life choices and advocates tolerance of lifestyles different from one's own. This outlook is grounded in an optimism about human nature and trust in the individual's responsibility to make sensible decisions. As a result, liberals assert that the government should remain neutral and allow individuals to pursue their goals without external interference. Other key liberal topics include the defense of private property and the rule of law.[63]

Most forms of liberalism support some form of free-market economy and capitalism. In a free market, the exchange of goods and services occurs with minimal state control and regulation. Instead, privately owned businesses compete with each other, and prices are primarily influenced by supply and demand.[64] Capitalism is an economic system in which the means of production are mainly privately owned. This system is typically characterized by a contrast between capitalist owners, who aim to maximize the profit of their investment, and workers, who sell their labor in exchange for a salary.[65]

One broad characterization distinguishes between classical and modern liberalism, also called social democratic liberalism, based on the role of the state. Classical liberalism seeks to protect the liberties and rights of individuals from government interference, arguing for a limited role of the state. It promotes negative liberty and tasks the state with safeguarding individuals from obstacles or interference from others, such as aggression and theft. Modern liberalism emphasizes positive liberty, arguing that the state should foster conditions that enable individuals to achieve their personal goals. This approach advocates for a more active role of the state to promote social justice, equality of opportunity, and the right to a minimal standard of living. This can include state programs to ensure affordable healthcare, education for all, and social security.[66]

Libertarianism is closely related to classical liberalism. It emphasizes individual liberties and argues that people should be free to do as they want without coercion as long as they do not infringe on the liberty of others. Some libertarians consider the non-aggression principle—the principle forbidding aggression against a person and their property— as the foundational tenet of libertarianism. Libertarians typically support a free-market economy based on private property and voluntary cooperation. They disapprove of governmental attempts to redistribute wealth and other forms of economic regulation. This view seeks to limit the role of government to collective defense, the protection of individual rights, and the enforcement of contracts.[67]

Various criticisms of liberalism have been formulated. One objection asserts that its individualistic focus on personal liberties undermines community, arguing that the prioritization of personal freedoms leads to social fragmentation. A different criticism proposes that private property and unregulated markets threaten economic equality and tend to create unjust hierarchies. Further objections argue that liberalism diminishes the common good by reinforcing individualistic social disputes and that its commitments to tolerance and pluralism result in cultural relativism.[68]

Socialism

Socialism is a family of political views emphasizing collective ownership and equal distribution of basic goods. It argues that the means of production belong to the people in general and the workers in particular and should therefore form part of social ownership rather than private property.[70] This outlook understands the state as a complex administrative device that manages resources and production to ensure social welfare and a fair distribution of goods.[71]

A key motivation underlying the socialist perspective is the establishment of equality, which is seen as the natural state of humans. Socialists seek to overcome sources of inequality, such as class systems and hereditary privileges. They are critical of capitalism, arguing that private property and free markets reinforce inequalities by leading to large-scale accumulation of private wealth.[72] Some socialists propose systems of regulation and taxation to mitigate the negative effects of free-market economies. Others reject free-market systems in general and promote different mechanisms to manage the production and distribution of goods, ranging from centralized state control and ownership to decentralized systems that plan and direct economic activity.[72]

Marxism is an influential school of socialism that focuses on the analysis of class relations and social conflicts. It rejects capitalism, arguing that it leads to inequality by dividing society into a capitalist class, which owns the means of production, and a working class, which has to sell its labor and is thereby alienated from the products of its labor. According to this view, economic forces and class struggles are the primary drivers of the historical development of political systems, eventually leading to the downfall of capitalism and the emergence of socialism and communism.[73] Communism is usually understood as a radical form of socialism that aims to replace private property with collective ownership and dissolve all class distinctions. In Marxist theory, socialism and communism are considered distinct types of post-capitalist societies. From this perspective, socialism is an intermediate stage between capitalism and communism that still carries some features of capitalism, such as material scarcity, a ruling government, and division of labor. Marx argued that these features would gradually dissolve, leading to a communist society characterized by material abundance, absence of occupational specialization, and self-organization without a central government.[74]

Various objections to socialism focus on its economic theory. Some argue that central planning and the absence of competition and market-driven price signals result in lower productivity and economic stagnation. Another line of criticism asserts that the different ideals motivating socialism are in conflict with each other. For example, the establishment of a massive state required to manage economic activity and social welfare may create new class distinctions, thereby undermining equality.[75]

Others

Environmentalism is a political ideology concerned with the relation between humans and nature. It seeks to preserve, restore, and enhance the natural environment, including the protection of landscapes and animals. Anthropocentric environmentalism advocates such policies to improve human life, for example, to mitigate the global consequences of climate change or to promote local environmental justice by protecting marginalized groups from regional environmental degradation. This form of environmentalism can be integrated in various other political ideologies, such as conservatism and socialism. Non-anthropocentric environmentalism, also called ecocentrism and deep ecology, differs by focusing on the intrinsic value of nature itself. This view emphasizes that humans are only a small part of the ecosystem as a whole. It seeks to protect and improve nature for its own sake, not only because it serves human interests. This outlook covers diverse and sometimes contrasting interpretations of the relation between humans and nature, including the belief that humans should act as custodians of nature and the idea that modern human civilizations are the source of the problem and threaten natural balance.[76]

Realism and idealism[f] are two opposing approaches to explaining and guiding political action. According to realism, political activity is primarily driven by self-interest and power. It asserts that actors use both soft and hard power to expand their own sphere of influence. Realists argue that politics should not be limited by moral constraints or shy away from violent conflicts when the power aspirations of different actors collide. They emphasize the importance of responding to concrete practical factors, with the primary goal of effectively shaping historical reality rather than pursuing ideals. Idealism, by contrast, asserts that political action should follow moral principles. It seeks to establish a just and fair social order based on universal ethical norms rather than narrow self-interest. Idealists reject established practices and institutions that promote unjust use of power and seek to replace them with fair governance, even if their idealized vision reflects a utopian aspiration distant from current circumstances.[79]

Consequentialism, perfectionism, and pluralism are distinct but overlapping views about which things are valuable and how values should guide political activity. According to consequentialism, the value of any action depends on its concrete consequences. Classical utilitarianism, an influential form of consequentialism, asserts that only happiness or pleasure is ultimately valuable. This view argues that politics should strive to produce the greatest amount of happiness for the greatest number of people.[80] Welfarism, a closely related view, promotes well-being, which can cover other features in addition to pleasure, such as health, personal growth, meaningful relationships, and a sense of purpose in life.[81] Perfectionism, a different evaluative outlook, asserts that there are certain objective goods, covering fields like morality, art, and culture, that promote the development of human nature. Although perfectionists disagree about what exactly those goods are, they all maintain that states should establish conditions that promote human excellence among their citizens.[82] Value pluralists assert that diverse values influence political action. They often emphasize that different values can be opposed to each other and that value conflicts cannot always be resolved. For example, Isaiah Berlin argued that liberty and equality are conflicting values and that a gain in one value cannot make up for the loss in the other.[83]

Individualism prioritizes the importance of individuals over the community, an ideal typically promoted by liberal political systems. It emphasizes that society is at its core made up of individuals and seeks to defend them from social attempts to interfere with their preferred lifestyles. Individualism contrasts with collectivism, which prioritizes the well-being of groups over individual interests and emphasizes the importance of group cohesion and unity. Communitarianism is a similar outlook that supports a social structure in which individuals are connected through strong social relationships and shared values. It argues that the personality and social identity of individuals are deeply influenced by community relations and social norms.[84] Nationalism extends the focus on social relations to the state as a whole. It is closely associated with patriotism and promotes social cohesion through national identity based on shared customs, culture, and language.[85]

Republicanism is a broad philosophical tradition that emphasizes civic virtue, political participation, and the rule of law. It argues that political action should promote the common good and social equality. This tradition is opposed to oppressive and authoritarian governance, advocating the separation of powers to prevent overconcentration of authority, encouraging citizens to participate in the political process, and seeking to hold the government accountable to the people.[86] Populism encompasses a variety of political outlooks that seek to promote the interests of ordinary people, typically contrasting the will of the people with the agenda of corrupt elites wielding power. The term is often associated with the negative connotation of attempting to gain support from uninformed people by appealing to popular sentiment.[87] Conversely, elitism is the belief that elites, rather than common people, should run the government.[88]

Various ideologies integrate religious values and principles into their political outlook. Christian democracy, an influential tradition in Western Europe, blends traditional Catholic social teachings with democratic principles, emphasizing community, family, a harmonious social order, respect for each person, and tradition together with a critique of the modern focus on material wealth and power.[89] Islamism seeks to incorporate Islamic principles into governance, including the implementation of Islamic law while maintaining a critical attitude towards Western influences.[90] Hindu nationalism promotes governance and national identity rooted in Hindu values and traditions.[91] Other religion-inspired political ideologies include Zionism, Buddhist socialism, and Confucianism.[92]

Contractarianism and contractualism are views about the sources and legitimacy of power. They argue that political authority should be based on some form of consent among the citizens, for example, as an implicit social contract or as what people would reasonably agree to under ideal circumstances.[93]

Postmodernism rejects ideological systems that claim to offer objective, universal truths, with a particularly critical attitude towards Enlightenment ideals of reason and progress. They oppose hierarchical power structures that perpetuate and enforce these ideals, calling instead for resistance to this type of centralized power while promoting a pluralism of local practices and ideologies.[94] Feminism, another critical approach, targets injustice based on gender, aiming to empower women and liberate them from unfair patriarchal social structures. Feminists focus on various forms of inequality, including social, economic, political, and legal inequality.[95]

Remove ads

Methodology

Summarize

Perspective

The methodology of political philosophy involves the critical examination of how to arrive at, justify, and criticize knowledge claims. It is particularly relevant in attempts to solve theoretical disagreements, such as disputes about the ideal form of government. Central to many methodological discussions is the evaluative or normative nature of political philosophy as a discipline that examines which values, norms, and societal arrangements are desirable. Disagreements about normative claims are usually less tractable than disagreements about empirical facts, which can typically be resolved through observation and experimentation. As a result, the different arguments presented in normative disagreements are frequently not sufficient to lead to generally accepted solutions. One interpretation suggests that these difficulties indicate that major parts of political philosophy[g] primarily express subjective views without a universally accepted rational foundation.[97]

Political philosophers sometimes start from common sense and established beliefs, which they systematically and critically review to assess their validity. This process includes the clarification of basic concepts, which can be used to formalize the underlying beliefs into precise theories while also considering arguments for and against them and exploring alternative views.[98] The methodologies of particularism and foundationalism propose different approaches to this enterprise. Particularists use a bottom-up approach and take individual intuitions or assessments of specific circumstances as their starting point. They seek to systematize these individual judgments into a coherent theoretical framework. Foundationalists, by contrast, employ a top-down approach. They begin their inquiry from wide-reaching principles, such as the maxim of classical utilitarianism, which evaluates actions and policies based on the pain-pleasure balance they produce. Foundationalism aims to construct comprehensive systems of political thought from a small number of basic principles.[99] The method of reflective equilibrium forms a middle ground between particularism and foundationalism. It tries to reconcile general principles with individual intuitions to arrive at a balanced and coherent framework that incorporates the perspectives from both approaches.[100]

A historically influential form of foundationalism grounds political ideologies in theories about human nature. It can take different forms, like reflections on human needs, abilities, and goals as well as the role of humans in the natural order or in a divine plan. Philosophers use these assumptions about human nature to infer political ideologies about the ideal form of government and other normative theories.[102] For example, Thomas Hobbes believed that the natural state of humans is a perpetual conflict, arguing that a strong state based on a general social contract is necessary to ensure stability and security.[103] An influential criticism of foundationalist approaches centered on human nature argues that one cannot infer normative claims from empirical facts, meaning that empirical facts about human nature do not provide a secure foundation for normative theories about the right form of government.[104]

Foundationalism is typically combined with universalism, which asserts that basic moral and political principles apply equally to every culture. Universalists suggest that the foundational values and standards of political action are the same for all societies and remain constant across historical periods. Cultural relativism rejects this transcultural perspective, arguing that norms and values are inherently tied to specific cultures. This view asserts that political principles represent assumptions of specific communities and cannot serve as universal standards for evaluating other cultures.[105]

Methodological individualism and holism are perspectives about the basic units of society. According to methodological individualism, societies are ultimately nothing but the individuals that comprise them. As a result, it analyzes political actions as the actions of the particular people who make decisions and participate within the social structure. This view sees collective entities, like states, nations, and other institutions, as a mere byproduct of individual actions. Methodological holists, by contrast, argue for the irreducible existence of collective entities in addition to individuals. They contend that collective entities are more than the sum of their parts and see them as essential elements of political explanations.[106]

Another methodological distinction is between rationalism and irrationalism. Rationalists assume that universal reason is or should be the guiding principle underlying political action. They see reason as a common thread that unites diverse societies and can ensure peace between them. Irrationalists reject this assumption and focus on other factors influencing human behavior, including emotions, cultural traditions, and social expectations. Some irrationalists argue for polylogism, the view that the laws of reason or logic are not universal but depend on cultural context, meaning that the same course of action may be rational from the perspective of one culture and irrational from another.[107][h]

Thought experiments are methodological devices in which political philosophers construct imagined situations to test the validity of political ideologies and explore alternative social arrangements. For example, in his thought experiment original position, John Rawls explores the underlying framework of a just society by imagining a situation in which individuals collectively decide the rules of their society. To ensure impartiality, individuals do not know which position they will occupy in this society, a condition termed veil of ignorance.[109]

Remove ads

History

Summarize

Perspective

Political philosophy has its roots in antiquity and many foundational concepts of Western political thought emerged in ancient Greek philosophy. Early influential contributions were made by the historian Thucydides (460–400 BCE), who inspired the school of realism by analyzing power relations and self-interest as central political factors.[111] Plato (428–348 BCE) discussed the role of the state, its relation to the citizens, the nature of justice, and forms of government. He was critical of democracy and favored a utopian monarchy ruled by a wise and benevolent philosopher king to promote the common good.[112] His student Aristotle (384–322 BCE) objected to Plato's utopianism, preferring a more practical approach to ensure political stability and avoid extremism. He defended perfectionism, asserting that humans have an inborn goal to develop their rational and moral capacities and that the state should foster this tendency.[113] In Roman philosophy, the stateman Cicero (106–43 BCE) infused Greek philosophy with Stoicism. He asserted that political action should be guided by reason rather than emotion and supported political participation following the meritocratic ideal of rule by the capable.[114]

Diverse traditions of political thought also developed in ancient China. Confucianism, initiated by Confucius (551–479 BCE), saw the virtue of humaneness or benevolence as the foundation of social order and norms. It sought to balance conflicting interests between private and public spheres, seeing society as an extension of the family.[115] Taoism, another tradition, focused on the relation between humans and nature, arguing that humans should act in harmony with the natural order of the universe while avoiding excessive desires. It is sometimes associated with anarchism because of its emphasis on natural order, spontaneity, and rejection of coercive authority.[116] Legalism, a realist school of thought, proposed that effective governance of large states requires strict laws based on rewards and punishments to control the harmful effects of personal self-interest.[117] In ancient India, various social and political theories emerged in the 2nd millennium BCE, recorded in the Rig Veda, like the idea that the social order is naturally divided into castes, each fulfilling a different role in society.[118] The Arthashastra, traditionally attributed to Kautilya (375–283 BCE)[119], was a political treatise on the essential components of states, such as king, ministers, territory, and army, describing their nature and interaction.[120] Buddhist political thought, starting in the 6th and 5th centuries BCE, rejected the strict caste division of Hindu society, focusing instead on universal equality, brotherhood, and the reduction of everyone's suffering.[121]

Political philosophy in the medieval period was characterized by the interplay between ancient Greek thought and religion.[123] Augustine (354–430 CE) saw states in the human world as fundamentally flawed compared to the divine ideal but also regarded them as vehicles for human improvement and the establishment of peace and order.[124] Influenced by Augustine's philosophy, Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274 CE) developed natural law theory by synthesizing Aristotelian and Christian philosophy. He argued that law serves the common good, positing that God rules the world according to the eternal law while humans participate in this plan by following the natural law, which reflects the moral order and can be known directly.[125]

In the Arabic–Persian tradition, philosophers sought to integrate Ancient Greek philosophy with Islamic thought. According to Al-Farabi (872–950), the state is a cooperative entity in which individuals voluntarily work together for common prosperity. Similar to Plato's vision, he imagines a hierarchical structure in which wise philosophers rule.[126] Al-Mawardi (972–1058) developed a complex theory of caliphates, examining how this form of government combines religious and political authority in the person of the caliph.[127] Following a descriptive approach, Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406) distinguished between natural states, which serve the worldly interests of the rulers, rational states, which serve the worldly interests of the people, and caliphates, which serve both worldly and otherworldly interests of the people.[128] Other influential contributions were made by Avicenna (980–1037), Al-Ghazali (1058–1111), and Averroes (1126–1198).[129] Meanwhile in China starting roughly 960 CE, neo-Confucian thinkers argued for decentralized governance. They identified two main functions of the government: to organize the social order and to morally educate citizens.[130]

In early modern philosophy, the medieval focus on religion was replaced by a secular outlook. The statesman Niccolò Machiavelli (1469–1527) defended a radical form of political realism, emphasizing the importance of power and pragmatic governance in which the ends justify the means.[131] Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) tried to provide a rational foundation for secular states. He argued that humans are naturally driven by egoism, leading to a war of all against all that can only be avoided through an authoritarian state justified by a common social contract.[132] As a founder of liberalism, John Locke (1632–1704) also based the state on the consent of the governed but prioritized individual freedom over state power. He suggested that humans are born free and equal, and that the primary objective of the state is to protect this natural condition.[133] David Hume (1711–1776) rejected social contracts as the foundation of the state, asserting instead that governments typically evolve without a prior plan and are accepted by the people because of their utility.[134] Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) introduced the concept of the general will, which is the will of the people to realize the common good.[135] Influenced by Rousseau, Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) argued that laws should reflect the general will of the people, asserting that every citizen has the fundamental right to freedom and the duty to uphold the social contract.[136] Edmund Burke (1729–1797), often considered the father of conservatism, stressed the importance of the accumulated wisdom of past generations while opposing radical change, such as the French Revolution.[137]

Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832) developed utilitarianism, promoting the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people. John Stuart Mill (1806–1873) adapted this philosophy to support classical liberalism.[139] According to Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831), the role of the state is the embodiment of ethical life and rational freedom, which he saw best realized in conservative, constitutional monarchies.[140] Influenced by Hegel, Karl Marx (1818–1883) and Friedrich Engels (1820–1895) analyzed the economic forces and class conflicts in capitalist societies, calling for a revolution to replace capitalism with socialism and communism.[141] Another radical reconceptualization of the social order was proposed by Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1809–1865), often regarded as the father of anarchism, who rejected state authority as an obstacle to liberty and equality.[142][i]

In the 20th century, interest in political philosophy declined as a result of criticisms of its normative claims and a shifting interest towards the more descriptive discipline of political science.[144] A central topic in the philosophy of Hannah Arendt (1906–1975) was the nature of totalitarian regimes, exemplified by Nazi Germany and Soviet Stalinism. She highlighted both their ability to mobilize the population through simplistic ideologies and their use of terror as an end in itself.[145] John Rawls (1921–2002) explored the nature of justice as fairness and examined the legitimate use of power in liberal democracies.[146] Inspired by Rawls, Robert Nozick (1938–2002) defended libertarianism, supporting a minimal state that protects individual rights and liberties.[147] The postmodern thinker Michel Foucault (1926–1984) analyzed power dynamics within society, with particular interest in how various societal institutions, such as medical and correctional institutions, shape human behavior through the interplay of knowledge and power.[148] In Indian political philosophy, Mahatma Gandhi (1869–1948) argued for self-rule and nonviolent resistance to colonialism while seeking to dismantle the caste system to achieve equality.[149] Sri Aurobindo (1872–1950) advocated for religious nationalism, which formed part of his broader philosophical worldview describing the spiritual evolution of the world as a whole.[150] In China, Marxism was reinterpreted and combined with Confucian thought, considering peasantry rather than the working class as the main force behind the communist revolution.[151] In the Islamic world, Islamic modernism sought to reconcile traditional Muslim teachings with modernity.[152]

Remove ads

See also

References

External links

Wikiwand - on

Seamless Wikipedia browsing. On steroids.

Remove ads