Jerry Lewis sits behind his huge desk, neatening the items that stand like sentries between us: a can of Diet Sunkist; a container of silver pens, tips up; a container of red pens, same position; a handful of green plastic surgical scalpels he uses to open mail, a dish of lemon drops. When you've been on the planet for almost nine decades, like Lewis has, and when you can't throw anything out ("I've kept everything!"), and when you're slightly nuts ("Did you ever see a man who can look at one eye with the other?"), you require order. At 85, Lewis employs three full-time people to help him stay organized. He loves them fiercely—and drives them bonkers.

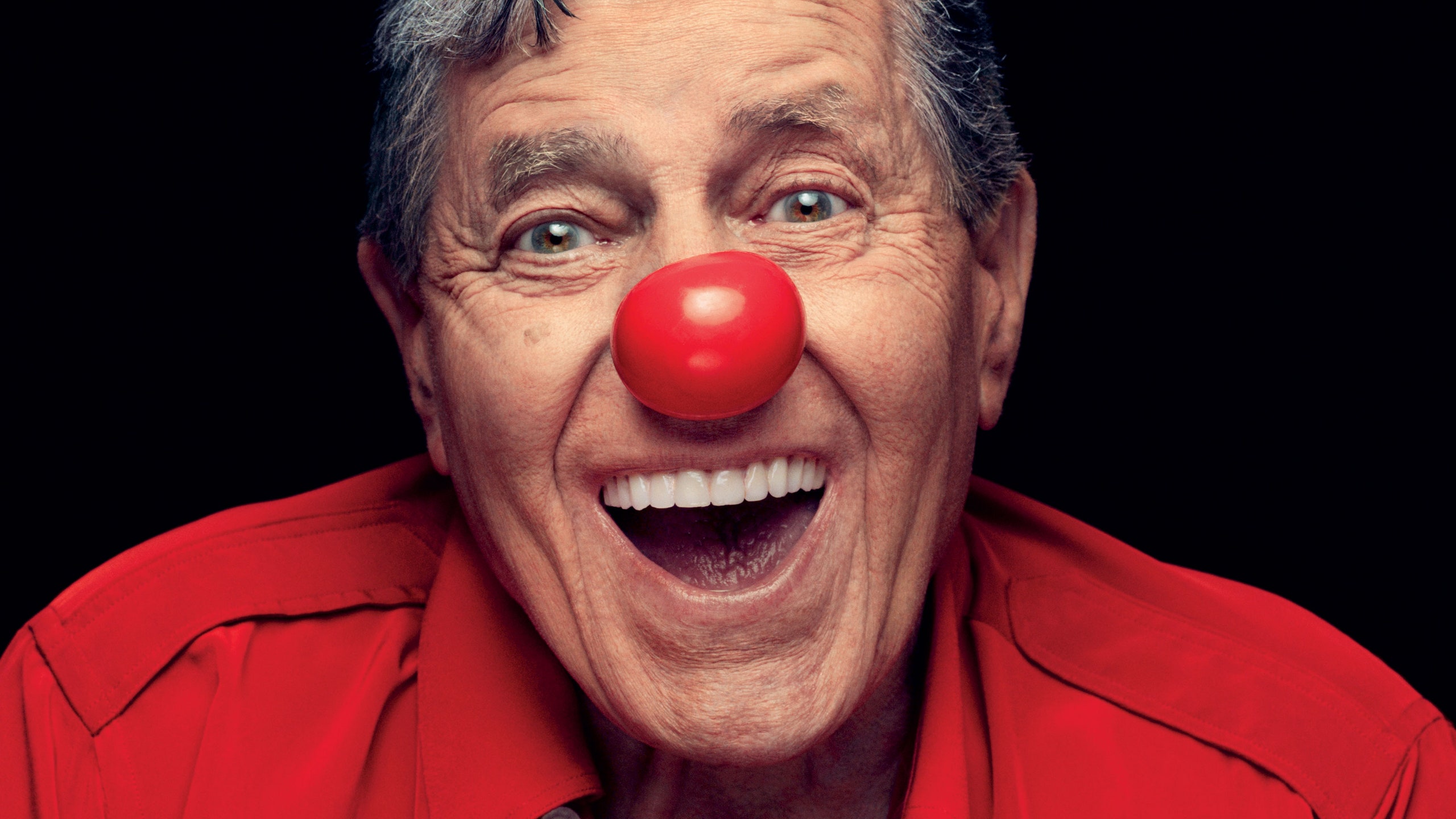

"Have you done anything today? Why not?" Lewis likes to bellow, his voice—three parts affection, one part curmudgeon—thundering through Jerry Lewis Films, a sprawling suite in an office park about four miles from the Las Vegas strip. He looks good—a little stooped, sure, but still sharp-eyed and quick-tongued and up-tempo, his red silk shirt unbuttoned low enough to reveal the scar from his double-bypass surgery twenty-nine years ago. On his feet are red velvet slippers embroidered with those iconic faces of Comedy and Tragedy. "Can I get another orange soda?" he asks, and when it arrives twenty seconds later: "What took you so long?"

Suddenly, Lewis's face goes blank and his hazel eyes get big as quarters. Slamming his chair back—boom!—he reaches for a trash can under his desk and expels a mouthful of soda in its general direction: a classic spit take. Except, he says, that it's not.

"Went down the wrong pipe," he announces, daintily dabbing at his mouth with a napkin. "I'm fine. It happens all the time, and when it does, you just have to let it." Getting older is crammed, he says, with such losses of control. "I'm taking Lasix, which makes me pee sometimes seven, eight, eleven, twelve times," he says. "I've decided to keep my fly open all day."

For hours now, we've been sitting around talking about funny—what it is, how it works, how to kill a joke, how to let it breathe. Lewis has thought a lot about these things since he got his first onstage laugh, accidentally kicking out a stage light at the age of 5. That was in 1931. In the intervening years, he became and remains the reigning master of the sight gag, the clown with the rubber face whose links to the foundations of American comedy are unmatched by anyone alive. This is a man, after all, who was tight with Charlie freakin' Chaplin, not to mention Stan Laurel and Al Jolson. This is a man who's met nine presidents and performed for four. As we talk, photos of many of those he holds dearest, may they rest in peace, look down from his crowded walls: John F. Kennedy, Frank Sinatra, Sammy Davis Jr., and the handsome crooner Lewis still calls "my partner" even though they broke up their act fifty-five years ago: Dean Martin.

In the 1940s and '50s, Martin and Lewis were—along with Sinatra and Elvis—the most famous people on earth. Later, though American critics were slow to recognize it, Lewis also became one of the few comic auteurs: a filmmaker who wrote, directed, produced, choreographed, edited, and starred in many of his own films, the best of which (The Nutty Professor, The Bellboy) have become bona fide classics. Tarantino and Spielberg are avowed Lewis fans. So is Scorsese. "He makes many people uncomfortable," the director says. "He doesn't censor himself as a performer, a filmmaker, or a public figure—which is difficult to accept for many people. I know there have been some books about him and some recognition in the past few years, but I think Americans are still coming to terms with Jerry and his astonishing artistry. It's as if they had to invent a new place for it, a new category.

"In a way, Jerry's movies never were embraced here, at least not in the way they've been in France," Scorsese continues, adding that what sets Lewis apart is his combination of mastery and vulgarity. "Jerry Lewis is still ahead of his time."

Comedians, on the other hand, have always recognized his gifts.

"If you don't get Jerry Lewis, you don't really understand comedy, because he is the essence of it," Jerry Seinfeld says in Method to the Madness of Jerry Lewis, a documentary slated to premiere on the Encore Network this fall. In a rough cut screened for me by the movie's director, Gregg Barson, who has worked with Lewis for three years on the project, Eddie Murphy lauds Lewis's "inspired silliness," calling him a genius. "Jerry is sexy," Carol Burnett proclaims, "when he's not doing 'Hey, lady!' "

Ask Lewis about Lewis, though, and the portrait he paints is a bit darker. "If you add up everything that makes the totality of the comic, there's a lot of shit there, pal, and you can't ignore it," he tells me. He has always clung, and clung mightily, to his inner child, and he admits his act is fueled by an unquenchable thirst for attention. "I need the applause," he'll say, sounding vulnerable, like the lonely boy who got shu±ed from relative to relative while his parents—vaudevillians, "show people"—went on the road. Lewis has described his early memories of Mom and Dad as "an occasional phone call or penny postcard." They even skipped his bar mitzvah. He felt, he says in one of his memoirs, like "a dummy, a misfit, the sorriest kid alive."

In adulthood, Lewis has at times been skewered for being "an egomaniacal, completely narcissistic, narrow-minded, arrogant, mean-spirited, temperamental, socially antiquated boor," as one critic summarized the vitriol. Even as he devoted himself to his annual Labor Day telethon that since 1966 has raised more than $1.6 billion to help children who suffer from muscular dystrophy ("Jerry's kids," he calls them), Lewis has sometimes been cast as a self-promotional control freak. "I'm a selfish man," he admits, though he argues that's not necessarily a bad thing. "You can't be faulted for being selfish if you're going to get better because of it. I make sure that I take good care of me."

Today, Lewis is very wealthy, but he's always looking for the next payday. He travels the world giving several speeches a year (for at least $75,000 a pop), is writing a screenplay (his forty-ninth), is slated to star in an independent film called Max Rose (now searching for financing), and is at work on a Broadway musical version of The Nutty Professor (with a score by Marvin Hamlisch) that he plans to direct. He recently met with John Travolta to discuss the actor's desire to remake Lewis's 1965 film The Family Jewels. And while it was announced in May that this Labor Day will be Lewis's last Muscular Dystrophy Association Telethon, retirement doesn't appear to sit well with him. Currently he is launching another telethon in Australia.

"There are times when I wonder where I get all of the goddamn energy," he says.

After spending eleven hours with him over two days, I've got a guess. Lewis's humor has always been instinctual—primitive, even; chaotic, seething with excitement, but at the same time simple in that it reflects the basic ridiculousness of the human condition. Peter Bogdanovich, the writer-director-actor who has known Lewis since the '60s, has written that his friend always "represented the frightened or funny 9-year-old in everybody, most especially the male," who, even as he got older, hid "a secret desire to resort to some form of infantilism in order to survive the hard knocks of life." To spend a couple of days with the man some have called the "Dark Prince" of American comedy is to grasp how true that is. The key to his longevity isn't Jerry's ego. Nor is it Jerry's kids. It's Jerry's ids.

Jerry Lewis has had a spectacular sex life. On the road, of course, girls were everywhere—in his dressing room, back at his hotel. But even at home, when he was directing a film, sometimes he'd get to the set early for "a little hump," just to get the day started right.

Joseph Levitch, as he was named upon his birth in Newark, New Jersey, had his first sexual experience seventy-three years ago, when he was 12. It was backstage at a club where his father, a singer and dancer who called himself Danny Lewis, was performing. The temptress was a twentysomething stripper named Trudine who lured the boy into her dressing room. "Whatever we did, I remember it took only a minute," Lewis recalls fondly. "She was a piece of work. She danced with a snake."

He married his first wife, Patti, a singer with Jimmy Dorsey's band, when he was 19. They'd met after he dropped out of high school to go on the road, starting at the bottom in burlesque houses where comics took the stage in between strippers. These were the kinds of dives that were patronized by "guys in the front with the newspapers in their laps and the trench coats—a tough room, but you had to do it."

Even then, the electricity of a laugh was intoxicating. But he'd never felt any high like the one he would feel with Martin. They met in 1945—Martin, a former bor whose Italian good looks made him "an Adonis," and Lewis, a 115-pound string bean, still fighting acne. Martin was 27—eight years older—"the big brother I never had," Lewis has said.

The act was an accident. Lewis was working a gig at Atlantic City's 500 Club, a flashy boardwalk spot that showcased unknowns, when he persuaded the owner to hire Martin to fill a gap. "We've worked together," Lewis lied. "We do a lot of funny stuff." In fact, they'd never officially performed as a duo. After Martin arrived, the owner demanded to see their material. Working from set pieces Lewis had learned in burlesque, they spitballed their act, jotting notes on the back of a pastrami wrapper (which Lewis still has; he keeps it in a safe-deposit box). "I felt lightning in a bottle right off," Lewis says. Martin, meanwhile, "thought I was insane. I said, 'Paul'—that's all I ever called him, his middle name—'Paul, listen to me. I think if we do everything right in the next six months we could be getting $5,000 a week.' He said, 'What are you talking about? We're getting $250 between us.' "

Two years later, the Adonis and the Monkey (as Lewis liked to be known) were making $15,000 a week. The reason: You never knew what would happen. Lewis was constantly flinging his body through space—off furniture, down stairs, into Martin's arms. "Hey, if I thought an audience was rough and it meant a fall, I'd go for it," he says. "What the hell? It won't be as smooth. But it will be funny." When Martin wanted to shut Lewis up, meanwhile, he wouldn't hesitate to shove his fingers right into his partner's mouth.

Their enjoyment of one another was palpable. When Orson Welles saw Martin and Lewis at the Copacabana nightclub in New York City, he once said, "people peed their pants." Don Rickles remembers seeing them early on, at the Capitol Theatre in New York City. "They were sensational. Magnificent," Rickles says. "Jerry was a wonderful all-around clown. I wouldn't say he was a great talker, but physically, facially, and everything, he was a riot. And Dean onstage was dynamite—a charming guy. A guy with style."

Bogdanovich never saw the duo live, but he's a connoisseur of the Colgate Comedy Hour, which aired on NBC from 1950 to 1955, when their shtick was at its most magical. "If you bottled that, you could save the world," Bogdanovich says. "It was this camaraderie they had—a shared sense of humor. It was just a delight."

Meanwhile, they were taking full advantage of their fame. Especially Lewis. "This is when I'm fucking everybody in Hollywood," he says flatly. Even after he and Martin split and Lewis began making movies solo, it was rumored he slept with all his leading ladies. He jokes that this can't be true, since one of his co-stars was Agnes Moorehead (a great actress, but no bombshell). Still, he acknowledges, even as Patti kept the home fires burning (they would have six sons), the smorgasbord of sex didn't slow down.

Asked for a list, he demurs, "That's not good press." But in the midst of another story, Lewis is suddenly insistent that Marilyn Monroe and President Kennedy—with whom Lewis was close—never had the affair many believe they had. When I look skeptical, he turns stern. "I'm telling you what I know. Never! And the only reason I know is because I did. Okay?"

Wait, what??

He nods, adding that Monroe used sex like he uses humor: to make an emotional connection. "She needed that contact to be sure it was real."

Okay, but what was it like, I ask, to make love to the most famously tragic sexpot of all time?

"It was…" he says, taking a beat, "long." He smiles ruefully. "I was crippled for a month." Another pause. "And I thought Marlene Dietrich was great!"

A Philly cheesesteak with extra mustard sits on Jerry Lewis's desk, untouched, next to his umpteenth orange soda. "What's happened at 85 is I've lost my appetite," he explains. "I used to be a little hog when I was young. But now I really don't seem to need it."

You have to be ravenous, however, to be funny. Of that, Lewis is certain. "Great comedy never came from Fifth Avenue," he told me when I first met him in 2005. "The young man who's had the Guggenheim fortune behind him all his life—he can hire all the authorities on the subject to teach him how to do a monologue, but he's never going to have the right stuff to pull it off. If he doesn't walk out onstage needing to walk out there, he doesn't have a dream of doing well.

"I tell young comics, 'Do you want this badly enough? It's there. But you have to go get it. And if you think I'm going to give you the key to the lock of that door, there is no key, there is no lock, and there is no door.' "

Now, six years later, he's still beating that drum. And he has an example that, to his mind, proves his point: Will Ferrell. "He is a wonderful technician. He does the script well. And he won't be here in eight years," he predicts. "He is a very good mechanic, but never expect a mechanic to hold you in his arms. He doesn't know how to do that. And you need that quality to have longevity." Seinfeld, on the other hand, "has got a heart on both sides," Lewis says. Similarly, he pronounces Chris Rock "very, very powerful. He comes from the place it's supposed to come from. My great-grandchildren will enjoy him."

At first I wonder if this analysis is the inevitable result of a generational shift. Is Lewis, who worked mostly in a pre-irony era, simply unable to grok Ferrell's style (which in Anchorman is, for me at least, as hilarious as it gets)? But Lewis is onto something. Ferrell's comedy can be cool to the touch in that he doesn't embody his characters as much as comment on them. Lewis, by contrast, inhabits the soul of the fool.

"If I were to teach a young man what he had to do to be good," Lewis tells me, "I'd say, 'Don't hold anything back.' You can't hold comedy back, because it needs to be exposed." That worldview reflects more than just a lack of irony. It reflects a raw need to turn one's self inside out—to not just allude to what's funny but to be it. "Funny is my life," he tells me. And thus it's worth risking everything for. "You've got to get down to the bottom," he says. "You go in."

With Dean Martin at his side, Lewis went in, went deep, and became a giant. But on July 24, 1956, ten years to the day after their debut in Atlantic City, they called it quits. They'd been chafing at each other—barely talking. Lewis says Martin was understandably weary of hearing everyone talk about his younger sidekick's wacky brilliance. In his 2005 memoir Dean Me: A Love Story, Lewis says that when he tried to reason with Martin by talking about the depth of their feelings for each other, Martin retorted with this: "You can talk about love all you want. To me, you're nothing but a fucking dollar sign."

That was it. The act was over. But in one way, Martin was right. Even alone, Lewis was money. His first solo film—The Delicate Delinquent, in 1957—was a hit, as were Rock-a-Bye Baby and The Geisha Boy. In 1959, around the time Paramount signed him to a $10 million deal, the studio told him it wanted to release his movie Cinderfella in the summer of 1960 instead of giving it the Christmas debut he envisioned. Lewis, adamant that Cinderfella was a holiday film, told them he'd make another movie to fill the summer spot. He wrote The Bellboy while working stand-up at the Fontainebleau Hotel in Miami Beach (where the movie would later be shot). He asked Billy Wilder to direct. But Wilder, who'd offered Lewis the Jack Lemmon role in Some Like It Hot, told him to do it himself. The experience would change Lewis's life.

The film is a masterpiece of physical comedy built around a simple idea: The bellboy never speaks, because nobody ever asks him a question. When Paramount got wind of this, ecutives worried that Lewis was making a silent movie. He told them they were wrong—everyone else in the movie talked!—but they were still queasy, so he offered to finance it himself. It cost just under $1 million to make. Over time, he says he's made hundreds of millions on that film alone. "People at Paramount hear the word bellboy, they get very nauseous," he says with a satisfied grin. "Some of them throw up right in your face."

He'd cause them more gastric distress by driving yet another hard bargain. So grateful were the studio brass for his box-office magic—by his estimate, he'd brought in $450 million in ticket revenues when tickets cost less than seventy-five cents—that when he turned 40, in 1966, they came to his party and publicly asked him what he wanted for a present. He didn't hesitate: In thirty years, all the rights to his films would revert back to him. They agreed. And in 1996, he got his wish.

"I'm smarter than a pig in shit, I promise you," Lewis tells me, leaning across the desk, a plastic scalpel in his hand. "I just don't like to let everybody know that, because you lose some tremendous ground if you let everybody know that you might have read a book."

To be funny is to admire funny, to revel in it. Jerry Lewis is supremely good at this. The man knows how to celebrate what he loves. A few examples:

Pranks. Once, probably sometime in the late 1940s, there was a birthday party for Eddie Cantor's wife, Ida. Among the guests: Fanny Brice, Leo Durocher, Danny Kaye, Judy Garland, Mickey Rooney, Jack Benny, George Burns, Gracie Allen, Milton Berle, and Lewis. Everyone's eating and talking and carrying on when, between the hors d'oeuvres and the brisket, Berle emerges from the kitchen with a tray of chopped liver.

"Milton comes out—you know where this is going, don't you?" Lewis asks. I nod. If it's a Milton Berle story, you can assume it involves Berle's legendary schlong. "It's laying on top of the chopped liver, surrounded by all the garnish!" Lewis exclaims, utterly delighted. "And he's walking around to each person at the party: 'Do you want some? Do you want some chopped liver?' He made fifteen to eighteen moves, and everyone is crippled with laughter. Crippled. I couldn't do anything but stare at it. I said, 'Jesus Christ. It's true.' "

His second wife, Sam; their 19-year-old daughter, Danielle ("The air in my lungs!"); and their two dogs, Rocky and Paulie (named for Martin). "Rocky is a Chihuahua. Paulie is a Jewhuahua, because he eats all my lox, all of my whitefish, and all of my bagels." Sam was a 28-year-old dancer when they met in Florida in 1979, while Lewis—then 52—was preparing to shoot what would be the surprise hit Hardly Working. "I fell in love with her pins," he says. "She didn't know what that meant. Pins are legs—I learned that in burlesque houses as a kid—and she had a set. She's 60 years old now, but my God, when she struts and we go out, the pins are there."

France. For years, when he got blue, his wife would send him there. "Anytime I got down, Sam said, 'Paris.' I'd get on a plane and go for three days. Have dinner, meet some friends, get back on the plane. I'm loaded with battery charge." The watch on his left wrist has two faces: Paris time and Vegas time.

Helping sick kids. "I understand naysayers," he says, making a face before adopting the syrupy voice he imagines they use to say, "His kids." "But they are mine, and I deal with them like that's my responsibility, and I am too far into it to step back."

Getting an Oscar. He won an honorary statuette for his humanitarian work in 2009. For years before he won it, several top directors—Bogdanovich and Scorsese among them—had argued that he was one of America's greatest filmmakers. In an eloquent plea that ran in the Los Angeles Times, David Weddle, now a producer and writer on the TV series CSI, quoted them and several others talking about Lewis's lasting impact: the 1960 invention he is widely credited with, the video assist, which allowed directors to see what they were shooting in real time (it's still in use today); his 1973 book about directing, The Total Film-Maker, which even now is read in film classes; the continuing impact of the students (Spielberg, George Lucas) who sat in on the directing class he taught for years at the University of Southern California. In the end, though, it was his work with kids—the same work that got him nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1977—that won him the Academy Award. Sure, it would have been nice to win for his films, he says, but winning is winning. "No difference," he says. "If I got the Oscar because I was setting up an orphanage for puppies, I don't care." He says he carries it everywhere—an exaggeration, I think. Though at the Cannes International Film Festival in 2009, he did pull it out of a duffel bag at a press conference.

Cash. "It feels good," he says, patting his right pants pocket, where he keeps the twenties and tens, his "tip money." In his left is the wad of hundreds and fifties—$4,000 or so, folded once, wrapped in a rubber band. It's his bookkeeper Violet's job to make sure that the immaculate bills are arranged, consecutively, by serial number. "I don't have anything but beautiful and crisp. I won't carry dirty money."

His staff. "They all have heart," he says. One attorney has worked for him for fifty-seven years, another for fifty. His accountant in L.A. has been on board fifty-four years. Violet, whom he sometimes addresses as "Your Majesty," has been in his Vegas office for twenty years or so, while David has been his personal assistant for the past four. And then there's his secretary, Penny, a full-blooded Cherokee Indian. She's a month older than he is, but seems two decades younger. Penny has worked for "the boss," as she calls him, for forty-eight years, and their shtick could be a stand-up act all on its own. A sampling:

Jerry Lewis went to a shrink once. After laying out his tale—only child, remote father, stratospheric success, painful breakup with partner, solo career, the whole gazinta, as he would say (a faux Yiddishism for what goes into), Lewis was stunned to hear the doctor say that it would be a mistake for him to undergo analysis. "What's that supposed to mean?" the comedian asked. "Well, if we peel away the emotional and psychological difficulties," the doctor responded, "your pain may leave, but it's also quite possible that you won't have a reason to be funny anymore."

So the root of all humor is—

"Pain," he says, cutting me off. Unanalyzed pain, of course.

Lewis has plenty of pain. All that pratfalling—even in the movies, he did all his own stunts—takes a toll on a body. Once, in 1965, he threw himself off a piano in the middle of a show at the Sands in Vegas, landed on the base of his spine, and spent four months in the hospital. He's had three surgeries on his spine alone. In the 1970s, he was taking thirteen Percodans a day for a while, then later quaaludes for the high and Nembutal for the come-down. He has described the years 1973 to 1977 as a complete blackout.

For two decades, the '50s and '60s, he'd averaged two pictures a year. But in the '70s, Lewis released just one film. He made a second but didn't finish it: The Day the Clown Cried, about a clown in a Nazi concentration camp. He was mercilessly criticized for attempting to mix comedy with the ultimate tragedy (though since he never completed it, no one ever saw a minute of the footage). In 1999, when Roberto Benigni's Life Is Beautiful won three Oscars for a similar story line, many noted that Lewis had tried it first.

Lewis's drive to create and his drive to destroy are all tangled up, it seems. Sometimes they act in tandem, especially in the editing room, where he frequently recuts scenes of finished films—his own, to be sure, but also other people's. Yes, you read that right: If he watches a film—any film—that he loves but finds himself irritated by, either for reasons of pacing or continuity or whatever-the-hell, he heads into the editing room and fis it, "just so when I run it next time, I'm not upset with it." He's done it hundreds of times, he says.

He learned this trick from Charlie Chaplin on a visit to his home in Lucerne, Switzerland, in 1963. Chaplin had invited him after seeing and admiring The Bellboy. When Lewis showed up, they spent hours talking about how to cut comedy, about tempo, about pace. "He said, 'Well, let's take The Bellboy. Give me the one place you think you should have gotten out of there.' That was his expression for the finish or the wrap-up. He would say, 'You've got to get out of there now. You've got the laugh. Go!' "

Lewis knew just the scene he wished he'd handled differently: the one in which the bellboy, Stanley, takes a photo of the gorgeous hotel at night and his flashbulb lights up all of Miami—turns night to day—but he doesn't even notice because he's so proud of his picture.

"I told him I wasn't happy with what I had for the payoff," Lewis says, recalling how after the daylight appears, the bellboy simply walks away from the camera. Lewis feared it wasn't clear to the audience how they were supposed to feel. Chaplin understood. "He said, 'You felt you didn't finish it. But at the preview, did they laugh at it?' I said, 'Yes, but they laughed uncertainly.' " It was then that Chaplin shared his secret. "He said, 'Why don't you do what I've done?' And he walks me back to his editing room, and he says, 'I made Monsieur Verdoux years ago, and for years I've been troubled with a scene that does not belong. So I made a cut in my print.' He cut the whole scene out! It was gone!"

Lately, Lewis has begun to edit his life, too. For years, in his memoirs and in interviews, he acknowledged feeling largely ignored by his parents. Now he prefers to describe his father as beneficent—a wise and generous man who taught him everything he knows. Bogdanovich—who met Danny Lewis and saw father and son together—remembers differently. He says theirs was "a strange relationship. Very cold. Jerry's become generous about it. But that didn't used to be the way he felt." Asked where Lewis's humor comes from, Bogdanovich doesn't hesitate: "Neglect as a child. That drives him."

Similarly, Lewis's feelings for Martin have become softer with the years. In 1976, two decades after breaking up, the former duo ended their feud on national television. It was Sinatra who persuaded Martin to surprise Lewis on his telethon, bringing the crowd to its feet and completely ambushing Lewis. (Nonetheless, he brought down the house, after dabbing away a tear, by asking Martin, "So, how ya been?") Later, Lewis was there for Martin after his son died when his fighter jet crashed in a snowstorm. Now that Martin's gone (he died in 1995 at the age of 78), Lewis has chosen to remember only the good times. He describes a night at Lindy's in New York when Martin ordered apple pie. "The pie comes to the table, he picks up the fork and does what we would all do, right?" Lewis pantomimes cutting the pie with the side of a fork, then stabbing the bite. "But the large part went into his mouth! He left the little piece." Lewis's eyes are wet. "Look at this!" he commands, pointing to his arms: goose bumps. "That's how impressed I was that night. He just did it, sipping coffee. He never mentioned it. I thought, 'Holy Christ. He doesn't know what he knows.' He knew when. The son of a bitch knew exactly when."

Jerry Lewis has always had a near-clairvoyant instinct for how his characters will be perceived by the public—with the glaring exception of his most famous creation, Buddy Love, the swinging alter ego of the bucktoothed Professor Julius Kelp in The Nutty Professor. In Lewis's script, Love was a "rude, discourteous egomaniac," his delivery as oily as his slicked-back hair. Yet to Lewis's surprise, America adored him—his skinny suits, his pink dress shirts, his supreme arrogance.

"He was so vile," Lewis says on the commentary track that accompanied the DVD release in 2005. "And then I got all this mail from women: 'I love Buddy Love!' "

In the upcoming Lewis documentary, Jerry Seinfeld offers a theory about why. After noting that Lewis "wanted to take the worst qualities of the worst people he had ever met and make them into this very unsympathetic character," Seinfeld says this: "Jerry is incapable of not putting love into everything he does. Buddy Love, as mean as he tried to play him, is lovable."

The observation sounds schmaltzy at first, but that's not how Seinfeld seems to mean it. He's getting at something fundamental about Lewis, whose films—as well-thought-out as they were—seem fueled less by intellect than by basic urges, needs, desires. In other words, by pure id.

Scorsese understood this when he asked Lewis to star in his 1983 film, The King of Comedy. Lewis plays Jerry Langford, a late-night-talk-show host who is being stalked by aspiring comic Rupert Pupkin (Robert De Niro). Pupkin yearns for fame; Langford has it and yearns for privacy. Lewis plays him bitter, reclusive, angry. His performance is searing. And autobiographical.

"Originally my name in the script was Robert Langford," Lewis tells me. "I said, 'Marty! We're going to be shooting in New York, Marty. Do yourself a favor and call him Jerry Langford.' He said, 'Why?' 'Because everywhere we go in New York, your construction workers and cab drivers will validate that it's Jerry.' And that's what happened. If you remember, in the movie, whenever I was in the street: 'Hey, Jerry.' 'Yo, Jer.' 'Hey there, you old schmuck.' It worked great for us. Whenever I went to New York, that's what happened. It still happens."

Jerry Lewis gets out of the shower some mornings and looks at himself in the full-length mirror with awe. "I say, 'I've used all those things there for eighty-five years.' They're going to break down." Not yet, though. Not quite yet. He knows what Chaplin would have said about a clean finish: "Get out of there now. You've got the laugh. Go!' " Still, he's not ready. "I've got so much to do," he says.

There's the project with Travolta, who confirms he's developing The Family Jewels "with my daughter and me in mind." (The reason: "Jerry Lewis was the biggest comedy star in the world when I was growing up," he says, calling Lewis an "inspiration.") There's the Nutty Professor musical, which Lewis has already cast and is determined to see on Broadway next year. There are sick kids in Australia that need his help.

Today, Lewis is all about survival. He gave up his decades-long habit of smoking five packs of cigarettes a day in 1982, when he had his double bypass. He's had prostate cancer, two heart attacks, and viral meningitis; he continues to manage diabetes and pulmonary fibrosis, the latter of which requires him to sleep with oxygen (and to carry it with him when he flies). He says his wife and daughter keep him alive, putting him to bed by nine thirty every night, making sure he eats, loving him.

Lewis is going to last to 101, he says. He has to. "My schedule for my demise is all laid out on paper," he says, ticking off his agenda: four years to watch his daughter get through college, two or three more years to "help her find a nice young man," and then about a decade of "kicking back and doing whatever work is easy for me to do. In the sixteenth year, I'll be one year older than Burns. I've got to beat George Burns, because I told him I was going to."

It was backstage at the MDA Telethon when Lewis laid down this challenge. They'd been friends forever, which is why Lewis could say to Burns, who was thirty years older and always addressed Lewis as "young man," that "whatever your last year is, I'm going a year after you." Burns, who would die at age 100 in 1996, responded with aplomb: "If that's what your dream is, sonny, go for it."

"It was a joke," Lewis tells me. "That's all it was." A beat. "Now it's no joke."

Amy Wallace is a GQ correspondent.