Supreme Court of North Carolina

| Supreme Court of North Carolina |

|---|

|

| Court Information |

| Justices: 7 |

| Founded: 1818 |

| Location: Raleigh, North Carolina |

| Salary |

| Associates: $197,802[1] |

| Judicial Selection |

| Method: Partisan election |

| Term: 8 years |

| Active justices |

| Trey Allen, Tamara Barringer, Phil Berger Jr., Richard Dietz, Anita Earls, Paul Martin Newby, Allison Riggs |

Founded in 1818, the North Carolina Supreme Court is the state's court of last resort and has seven judgeships. The current chief of the court is Paul Martin Newby.

As of August 2024, one judge on the court was appointed, one was elected in a partisan election as a Democrat, and five were elected in partisan elections as Republicans.

The North Carolina Supreme Court meets in the Justice Building in Raleigh, North Carolina.[2] The chief justice sets the schedule of the court.[3]

In North Carolina, state supreme court justices are elected in partisan elections. There are eight states that use this selection method. To read more about the partisan election of judges, click here.

Jurisdiction

The supreme court is the state's highest court. The court hears oral arguments in cases appealed from lower courts. The court considers errors in legal procedures or judicial interpretation of the law. The court primarily hears cases involving questions of constitutional law, consequential legal questions, and death penalty or first degree murder appeals.[4] The court also automatically hears cases involving rate determinations by the North Carolina Utilities Commission.[5]

The court is required to create appellate rules, remove or censure unfit judges (original jurisdiction), and oversee aspects of the practice of law in the state. The general assembly also created the administrative office of the courts to handle administration and budgeting services of the state courts, and its director is appointed by the chief justice.[6]

The chief justice is required to preside over the court for an impeachment trial of the governor or lieutenant governor and to supervise and manage the assignment of judges in certain other courts.[7]

The following text from Article IV, Section 12 of the North Carolina Constitution covers the jurisdiction of the court:

| “ |

The Supreme Court shall have jurisdiction to review upon appeal any decision of the courts below, upon any matter of law or legal inference. The jurisdiction of the Supreme Court over "issues of fact" and "questions of fact" shall be the same exercised by it prior to the adoption of this Article, and the Court may issue any remedial writs necessary to give it general supervision and control over the proceedings of the other courts. The Supreme Court also has jurisdiction to review, when authorized by law, direct appeals from a final order or decision of the North Carolina Utilities Commission. [8] |

” |

| —North Carolina Constitution, Article IV, Section 12 | ||

Justices

The table below lists the current justices of the Supreme Court of North Carolina, their political party, and when they assumed office.

| Office | Name | Party | Date assumed office |

|---|---|---|---|

| North Carolina Supreme Court | Trey Allen | Republican | January 1, 2023 |

| North Carolina Supreme Court | Tamara Barringer | Republican | January 1, 2021 |

| North Carolina Supreme Court | Phil Berger Jr. | Republican | January 1, 2021 |

| North Carolina Supreme Court | Richard Dietz | Republican | January 1, 2023 |

| North Carolina Supreme Court | Anita Earls | Democratic | January 1, 2019 |

| North Carolina Supreme Court | Paul Martin Newby | Republican | January 1, 2005 |

| North Carolina Supreme Court | Allison Riggs | Democratic | September 11, 2023 |

Judicial selection

- See also: Judicial selection in North Carolina

The seven justices of the North Carolina Supreme Court are chosen through partisan elections. Justices are elected to eight-year terms and must face re-election if they wish to serve again.[9]

Qualifications

To serve on this court, a person must be licensed to practice law in North Carolina. There is a mandatory retirement age of 72 years.[10]

Chief justice

The chief justice of the supreme court is elected by voters to serve in that capacity for an eight-year term.[11]

Vacancies

In the event of a midterm vacancy, the governor appoints a successor to serve until the next general election which is held more than 60 days after the vacancy occurs. The governor must select an appointee from a list of three recommendations provided by the executive committee of the political party with which the vacating justice was affiliated.[12] An election is then held for a full eight-year term.[13][9]

The map below highlights how vacancies are filled in state supreme courts across the country.

Elections

- See also: North Carolina Supreme Court elections

Elections are held in even-numbered years. These elections were nonpartisan from 2004 to 2018.[14]

2024

The term of one North Carolina Supreme Court justice expired on December 31, 2024. The one seat was up for partisan election on November 5, 2024. The primary was March 5, 2024, and a primary runoff was May 14, 2024. The filing deadline was December 15, 2023.

Candidates and results

General election

General election for North Carolina Supreme Court

Incumbent Allison Riggs and Jefferson Griffin ran in the general election for North Carolina Supreme Court on November 5, 2024.

Candidate | ||

| Allison Riggs (D) | |

| Jefferson Griffin (R) | |

= candidate completed the Ballotpedia Candidate Connection survey. = candidate completed the Ballotpedia Candidate Connection survey. | ||||

| If you are a candidate and would like to tell readers and voters more about why they should vote for you, complete the Ballotpedia Candidate Connection Survey. | ||||

Do you want a spreadsheet of this type of data? Contact our sales team. | ||||

Democratic primary election

Democratic primary for North Carolina Supreme Court

Incumbent Allison Riggs defeated Lora Cubbage in the Democratic primary for North Carolina Supreme Court on March 5, 2024.

Candidate | % | Votes | ||

| ✔ |  | Allison Riggs | 69.1 | 450,268 |

| Lora Cubbage | 30.9 | 201,336 | |

| Total votes: 651,604 | ||||

= candidate completed the Ballotpedia Candidate Connection survey. = candidate completed the Ballotpedia Candidate Connection survey. | ||||

| If you are a candidate and would like to tell readers and voters more about why they should vote for you, complete the Ballotpedia Candidate Connection Survey. | ||||

Do you want a spreadsheet of this type of data? Contact our sales team. | ||||

Republican primary election

The Republican primary election was canceled. Jefferson Griffin advanced from the Republican primary for North Carolina Supreme Court.

2022

The terms of two North Carolina Supreme Court justices expired on December 31, 2022. The two seats were up for partisan election on November 8, 2022.

Candidates and results

Seat 3: Hudson vacancy

General election

General election for North Carolina Supreme Court

Richard Dietz defeated Lucy N. Inman in the general election for North Carolina Supreme Court on November 8, 2022.

Candidate | % | Votes | ||

| ✔ |  | Richard Dietz (R) | 52.4 | 1,965,840 |

| Lucy N. Inman (D)  | 47.6 | 1,786,650 | |

| Total votes: 3,752,490 | ||||

= candidate completed the Ballotpedia Candidate Connection survey. = candidate completed the Ballotpedia Candidate Connection survey. | ||||

| If you are a candidate and would like to tell readers and voters more about why they should vote for you, complete the Ballotpedia Candidate Connection Survey. | ||||

Do you want a spreadsheet of this type of data? Contact our sales team. | ||||

Democratic primary election

The Democratic primary election was canceled. Lucy N. Inman advanced from the Democratic primary for North Carolina Supreme Court.

Republican primary election

The Republican primary election was canceled. Richard Dietz advanced from the Republican primary for North Carolina Supreme Court.

Seat 5: Ervin's seat

General election

General election for North Carolina Supreme Court

Trey Allen defeated incumbent Sam Ervin IV in the general election for North Carolina Supreme Court on November 8, 2022.

Candidate | % | Votes | ||

| ✔ |  | Trey Allen (R)  | 52.2 | 1,957,440 |

| Sam Ervin IV (D)  | 47.8 | 1,792,873 | |

| Total votes: 3,750,313 | ||||

= candidate completed the Ballotpedia Candidate Connection survey. = candidate completed the Ballotpedia Candidate Connection survey. | ||||

| If you are a candidate and would like to tell readers and voters more about why they should vote for you, complete the Ballotpedia Candidate Connection Survey. | ||||

Do you want a spreadsheet of this type of data? Contact our sales team. | ||||

Democratic primary election

The Democratic primary election was canceled. Incumbent Sam Ervin IV advanced from the Democratic primary for North Carolina Supreme Court.

Republican primary election

Republican primary for North Carolina Supreme Court

Trey Allen defeated April C. Wood and Victoria Prince in the Republican primary for North Carolina Supreme Court on May 17, 2022.

Candidate | % | Votes | ||

| ✔ |  | Trey Allen  | 55.4 | 385,124 |

| April C. Wood | 36.3 | 252,504 | |

| Victoria Prince | 8.3 | 57,672 | |

| Total votes: 695,300 | ||||

= candidate completed the Ballotpedia Candidate Connection survey. = candidate completed the Ballotpedia Candidate Connection survey. | ||||

| If you are a candidate and would like to tell readers and voters more about why they should vote for you, complete the Ballotpedia Candidate Connection Survey. | ||||

Do you want a spreadsheet of this type of data? Contact our sales team. | ||||

Justices not on the ballot

- Robin Hudson (D)

2020

The terms of three North Carolina Supreme Court justices expired on December 31, 2020. The three seats were up for partisan election on November 3, 2020.

Candidates and election results

Chief justice: Beasley's seat

General election

General election for North Carolina Supreme Court

Paul Martin Newby defeated incumbent Cheri Beasley in the general election for North Carolina Supreme Court on November 3, 2020.

Candidate | % | Votes | ||

| ✔ |  | Paul Martin Newby (R)  | 50.0 | 2,695,951 |

| Cheri Beasley (D) | 50.0 | 2,695,550 | |

| Total votes: 5,391,501 | ||||

= candidate completed the Ballotpedia Candidate Connection survey. = candidate completed the Ballotpedia Candidate Connection survey. | ||||

| If you are a candidate and would like to tell readers and voters more about why they should vote for you, complete the Ballotpedia Candidate Connection Survey. | ||||

Do you want a spreadsheet of this type of data? Contact our sales team. | ||||

Democratic primary election

The Democratic primary election was canceled. Incumbent Cheri Beasley advanced from the Democratic primary for North Carolina Supreme Court.

Republican primary election

The Republican primary election was canceled. Paul Martin Newby advanced from the Republican primary for North Carolina Supreme Court.

Seat 2: Newby's seat

General election

General election for North Carolina Supreme Court

Phil Berger Jr. defeated Lucy N. Inman in the general election for North Carolina Supreme Court on November 3, 2020.

Candidate | % | Votes | ||

| ✔ |  | Phil Berger Jr. (R) | 50.7 | 2,723,704 |

| Lucy N. Inman (D) | 49.3 | 2,652,187 | |

| Total votes: 5,375,891 | ||||

= candidate completed the Ballotpedia Candidate Connection survey. = candidate completed the Ballotpedia Candidate Connection survey. | ||||

| If you are a candidate and would like to tell readers and voters more about why they should vote for you, complete the Ballotpedia Candidate Connection Survey. | ||||

Do you want a spreadsheet of this type of data? Contact our sales team. | ||||

Democratic primary election

The Democratic primary election was canceled. Lucy N. Inman advanced from the Democratic primary for North Carolina Supreme Court.

Republican primary election

The Republican primary election was canceled. Phil Berger Jr. advanced from the Republican primary for North Carolina Supreme Court.

Seat 4: Davis' seat

General election

General election for North Carolina Supreme Court

Tamara Barringer defeated incumbent Mark A. Davis in the general election for North Carolina Supreme Court on November 3, 2020.

Candidate | % | Votes | ||

| ✔ |  | Tamara Barringer (R) | 51.2 | 2,746,362 |

| Mark A. Davis (D) | 48.8 | 2,616,265 | |

| Total votes: 5,362,627 | ||||

= candidate completed the Ballotpedia Candidate Connection survey. = candidate completed the Ballotpedia Candidate Connection survey. | ||||

| If you are a candidate and would like to tell readers and voters more about why they should vote for you, complete the Ballotpedia Candidate Connection Survey. | ||||

Do you want a spreadsheet of this type of data? Contact our sales team. | ||||

Democratic primary election

The Democratic primary election was canceled. Incumbent Mark A. Davis advanced from the Democratic primary for North Carolina Supreme Court.

Republican primary election

The Republican primary election was canceled. Tamara Barringer advanced from the Republican primary for North Carolina Supreme Court.

2018

The term of one North Carolina Supreme Court justice expired on December 31, 2018. Incumbent Barbara Jackson (R) stood for partisan election on November 6, 2018. Anita Earls (D) defeated Jackson and Chris Anglin (R) to win the position.

Candidates and results

Seat 1: Jackson's seat

General election

General election for North Carolina Supreme Court

Anita Earls defeated incumbent Barbara Jackson and Chris Anglin in the general election for North Carolina Supreme Court on November 6, 2018.

Candidate | % | Votes | ||

| ✔ |  | Anita Earls (D)  | 49.6 | 1,812,751 |

| Barbara Jackson (R) | 34.1 | 1,246,263 | |

| Chris Anglin (R) | 16.4 | 598,753 | |

| Total votes: 3,657,767 (100.00% precincts reporting) | ||||

= candidate completed the Ballotpedia Candidate Connection survey. = candidate completed the Ballotpedia Candidate Connection survey. | ||||

| If you are a candidate and would like to tell readers and voters more about why they should vote for you, complete the Ballotpedia Candidate Connection Survey. | ||||

Do you want a spreadsheet of this type of data? Contact our sales team. | ||||

Caseloads

The table below details the number of cases filed with the court and the number of dispositions (decisions) the court reached in each year.[20]

| North Carolina Supreme Court caseload data | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Filings | Dispositions |

| 2020-2021 | 634 | 371 |

| 2019-20 | 671 | 560 |

| 2018-19 | 728 | 586 |

| 2017-18 | 655 | 631 |

| 2016-17 | 646 | 607 |

| 2015-16 | 678 | 666 |

| 2014-15 | 676 | 676 |

| 2013-14 | 730 | 733 |

| 2012-13 | 771 | 779 |

| 2011-12 | 744 | 688 |

| 2010-11 | 762 | 727 |

| 2009-10 | 769 | 753 |

| 2008-09 | 736 | 736 |

| 2007-08 | 773 | 794 |

| 2006-07 | 785 | 744 |

Analysis

Ballotpedia Courts: Determiners and Dissenters (2021)

In 2020, Ballotpedia published Ballotpedia Courts: Determiners and Dissenters, a study on how state supreme court justices decided the cases that came before them. Our goal was to determine which justices ruled together most often, which frequently dissented, and which courts featured the most unanimous or contentious decisions.

In 2020, Ballotpedia published Ballotpedia Courts: Determiners and Dissenters, a study on how state supreme court justices decided the cases that came before them. Our goal was to determine which justices ruled together most often, which frequently dissented, and which courts featured the most unanimous or contentious decisions.

The study tracked the position taken by each state supreme court justice in every case they decided in 2020, then tallied the number of times the justices on the court ruled together. We identified the following types of justices:

- We considered two justices opinion partners if they frequently concurred or dissented together throughout the year.

- We considered justices a dissenting minority if they frequently opposed decisions together as a -1 minority.

- We considered a group of justices a determining majority if they frequently determined cases by a +1 majority throughout the year.

- We considered a justice a lone dissenter if he or she frequently dissented alone in cases throughout the year.

Summary of cases decided in 2020

- Number of justices: 7

- Number of cases: 179

- Percentage of cases with a unanimous ruling: 66.5% (119)

- Justice most often writing the majority opinion: Ervin (28)

- Per curiam decisions: 18

- Concurring opinions: 7

- Justice with most concurring opinions: Ervin (2)

- Dissenting opinions: 51

- Justice with most dissenting opinions: Newby (26)

For the study's full set of findings in North Carolina, click here.

Ballotpedia Courts: State Partisanship (2020)

- See also: Ballotpedia Courts: State Partisanship

Last updated: June 15, 2020

Last updated: June 15, 2020

In 2020, Ballotpedia published Ballotpedia Courts: State Partisanship, a study examining the partisan affiliation of all state supreme court justices in the country as of June 15, 2020.

The study presented Confidence Scores that represented our confidence in each justice's degree of partisan affiliation, based on a variety of factors. This was not a measure of where a justice fell on the political or ideological spectrum, but rather a measure of how much confidence we had that a justice was or had been affiliated with a political party. To arrive at confidence scores we analyzed each justice's past partisan activity by collecting data on campaign finance, past political positions, party registration history, as well as other factors. The five categories of Confidence Scores were:

- Strong Democrat

- Mild Democrat

- Indeterminate[21]

- Mild Republican

- Strong Republican

We used the Confidence Scores of each justice to develop a Court Balance Score, which attempted to show the balance among justices with Democratic, Republican, and Indeterminate Confidence Scores on a court. Courts with higher positive Court Balance Scores included justices with higher Republican Confidence Scores, while courts with lower negative Court Balance Scores included justices with higher Democratic Confidence Scores. Courts closest to zero either had justices with conflicting partisanship or justices with Indeterminate Confidence Scores.[22]

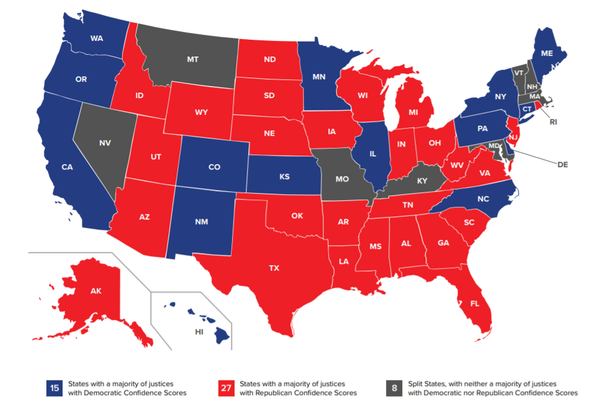

North Carolina had a Court Balance Score of -8.86, indicating Democrat control of the court. In total, the study found that there were 15 states with Democrat-controlled courts, 27 states with Republican-controlled courts, and eight states with Split courts. The map below shows the court balance score of each state.

Bonica and Woodruff campaign finance scores (2012)

In October 2012, political science professors Adam Bonica and Michael Woodruff of Stanford University attempted to determine the partisan outlook of state supreme court justices in their paper, "State Supreme Court Ideology and 'New Style' Judicial Campaigns." A score above 0 indicated a more conservative-leaning ideology while scores below 0 were more liberal. The state Supreme Court of North Carolina was given a campaign finance score (CFscore), which was calculated for judges in October 2012. At that time, North Carolina received a score of -0.01. Based on the justices selected, North Carolina was the 25th most liberal court. The study was based on data from campaign contributions by judges themselves, the partisan leaning of contributors to the judges, or—in the absence of elections—the ideology of the appointing body (governor or legislature). This study was not a definitive label of a justice but rather an academic gauge of various factors.[23]

Noteworthy cases

The following are noteworthy cases heard before the North Carolina Supreme Court. For a full list of opinions published by the court, click here. Know of a case we should cover here? Let us know by emailing us.

Moore v. Harper

- See also Moore v. Harper

Moore v. Harper was a lawsuit filed in the Wake County Superior Court in November 2021 in response to North Carolina's redistricting after the 2020 census.

On Nov. 16, 2021, the North Carolina League of Conservation Voters filed a lawsuit before the Wake County Superior Court challenging the validity of the state's enacted legislative and congressional maps. In the suit, plaintiffs said "this suit is about harnessing the power of mathematics and computer science to identify and remedy the severe constitutional flaws in the redistricting maps recently enacted by the North Carolina General Assembly," and that the enacted maps " create (and intentionally create) a severe partisan gerrymander" and "dilute the voting power of North Carolina’s black citizens."[24] The plaintiffs asked the court "to set aside the unlawful Enacted Plans and, as interim relief, to enjoin the use of the Enacted Plans in the 2022 primary and general elections" and to require the North Carolina State Legislature to draw new maps.

On Dec. 8, the North Carolina Supreme Court issued a joint ruling in this case and Harper v. Lewis delaying the state's 2022 candidate filing period and primary elections.[25] This was the fourth in a series of rulings on the issue. Initially, the Wake County Superior Court denied the request to delay the filing period and election on Dec. 3.[26] The North Carolina Court of Appeals then issued a stay on Dec. 6 granting the plaintiffs' request, then issued a second ruling on Dec. 6 reversing its decision.[27][28]

On Jan. 11, 2022, the Wake County Superior Court ruled in support of the new maps.[29] In its opinion, the three-judge panel said: "All of Plaintiffs' claims in these lawsuits, in essence, stem from the basic argument that the 2021 redistricting maps passed by the North Carolina General Assembly are unconstitutional under the North Carolina Constitution. We have taken great lengths to examine that document. At the end of the day, after carefully and fully conducting our analysis, it is clear that Plaintiffs’ claims must fail."[30]

On Feb. 4, the North Carolina Supreme Court ruled that the congressional and legislative maps were unconstitutional, and ordered the maps be redrawn. The ruling established a Feb. 18 deadline for the North Carolina General Assembly and intervenors in the lawsuit to submit new maps to a trial court, which would then adopt a new set of maps by Feb. 23. Challenges to the new maps would also need to be filed by Feb. 23.[31]

Justice Robin Hudson wrote in the ruling that the maps were "unconstitutional beyond a reasonable doubt under the free elections clause, the equal protection clause, the free speech clause, and the freedom of assembly clause of the North Carolina Constitution." Chief Justice Paul Newby dissented, writing : "I dissent from the decision of the Court which violates separation of powers by effectively placing responsibility for redistricting with the judicial branch, not the legislative branch as expressly provided in our constitution."[31]

On Feb. 15, the Wake County Superior Court appointed three former judges to act as redistricting special masters: former Superior Court Judge Tom Ross, a Democrat, former state Supreme Court Justice Bob Orr, an independent, and former state Supreme Court Justice Bob Edmunds, a Republican.[32]

On Feb. 23, the Wake County Superior Court ruled to approve state legislative maps redrawn by the North Carolina General Assembly. The court struck down the Assembly's redrawn congressional map and instead enacted a map drawn by the redistricting special masters.[33]

On March 17, 2022, Speaker of the North Carolina House of Representatives Timothy K. Moore (R) filed a petition for a writ of certiorari to the U.S. Supreme Court, which granted review on June 30, 2022. Oral argument in Moore v. Harper took place before SCOTUS on December 7, 2022.

On December 16, 2022, the North Carolina Supreme Court issued an opinion affirming the February 2022 decision of the Wake County Superior Court that rejected the remedial congressional redistricting plan that the General Assembly adopted (RCP) and adopted the Modified remedial congressional redistricting plan (Modified RCP) that the court-appointed special masters developed.[34]

On January 20, 2023, the North Carolina legislature petitioned the North Carolina Supreme Court to rehear Moore v. Harper, and on February 3, 2023, the state supreme court voted to re-hear the case on March 14, 2023. As a result of the 2022 elections, the court flipped from a 4-3 Democratic majority to a 5-2 Republican majority.[35][36] On March 14, 2023, the North Carolina Supreme Court re-heard oral argument in Moore v. Harper.

On June 27, 2023, in a 6-3 opinion, the court held that it had jurisdiction to rule in the case, regardless of whether the North Carolina Supreme Court reversed its original decision (referred to as Harper I) that the state's congressional district boundaries violated the state constitution.[37] The court's opinion stated, "This Court has jurisdiction to review the judgment of the North Carolina Supreme Court in Harper I that adjudicated the Federal Elections Clause issue...The North Carolina Supreme Court’s decision to withdraw Harper II and overrule Harper I does not moot this case."[37]

The court also affirmed the initial decision of the North Carolina Supreme Court which overturned the state's 2021 congressional map, holding that "State courts retain the authority to apply state constitutional restraints when legislatures act under the power conferred upon them by the Elections Clause."[37] Although the state supreme court later reversed its decision, the court upheld the state court's authority to decide whether the district boundaries complied with state law. Chief Justice John Roberts delivered the majority opinion of the court.[37]

Dickson v. Rucho

Dickson v. Rucho was a lawsuit filed in the Wake County Superior Court in November 2011 in response to North Carolina's redistricting after the 2010 census. The plaintiffs alleged that certain districts were unconstitutionally racially gerrymandered. A three-judge panel of the superior court upheld the redistricting plan in July 2013.[38]

In December 2014, the North Carolina Supreme Court affirmed the superior court's decision, concluding, "We agree with the unanimous three-judge panel that the General Assembly’s enacted plans do not violate plaintiffs’ constitutional rights. We hold that the enacted House and Senate plans satisfy state and federal constitutional and statutory requirements."[39]

The case was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. On April 20, 2015, the U.S. Supreme Court vacated the North Carolina Supreme Court's judgment and remanded the case back to the state supreme court. The U.S. Supreme Court instructed the North Carolina Supreme Court to review the case in light of its decision in another redistricting case, Alabama Legislative Black Caucus v. Alabama (2015).[40][41]

On December 18, 2015, the North Carolina Supreme Court concluded, "We hold ... that the three-judge panel’s decision fully complies with the Supreme Court’s decision in Alabama. Accordingly, we reaffirm the three-judge panel’s Judgment and Memorandum of Decision."[42]

This ruling was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court in April 2016. On May 30, 2017, the U.S. Supreme Court vacated the state supreme court's judgment and remanded the case in light of its ruling in Cooper v. Harris (2017).[43][44] The North Carolina Supreme Court remanded the case to the Wake County Superior Court to "determine whether (1) in light of Cooper v. Harris and North Carolina v. Covington, a controversy exists or if this matter is moot in whole or in part; (2) there are other remaining collateral state and/or federal issues that require resolution; and (3) other relief may be proper."[45]

On February 11, 2018, the same three-judge Wake County Superior Court panel concluded that "the doctrine of mootness and judicial economy dictate that this litigation be declared to be concluded. The legislative and congressional maps now under consideration in federal courts are not the product of the 2011 redistricting legislation considered by this trial court, but rather the product of later acts of the General Assembly. ... The 2011 Redistricting Plans no longer exist. ... While Plaintiffs are certainly not foreclosed from seeking redress in the General Court of Justice of North Carolina for state constitutional claims that may become apparent in the 2016 and 2017 redistricting plans, those claims ought best be asserted in new litigation."[38]

The case was ultimately dismissed by the North Carolina Supreme Court in January 2019.[46]

Ethics

The North Carolina Code of Judicial Conduct sets forth ethical guidelines and principles for the conduct of judges and judicial candidates in North Carolina. It is composed of seven canons:

- Canon 1: "A judge should uphold the integrity and independence of the judiciary."

- Canon 2: "A judge should avoid impropriety in all the judge’s activities."

- Canon 3: Titled "A judge should perform the duties of the judge’s office impartially and diligently," outlines the responsibilities of judges and when they should disqualify themselves from a case.

- Canon 4: "A judge may participate in cultural or historical activities or engage in activities concerning the legal, economic, educational, or governmental system, or the administration of justice."

- Canon 5: "A judge should regulate the judge’s extra-judicial activities to ensure that they do not prevent the judge from carrying out the judge’s judicial duties." In part, this canon notes that a judge should not practice law.

- Canon 6: "A judge should regularly file reports of compensation received for quasi-judicial and extra-judicial activities."

- Canon 7: Describes what political activity is permissible: "A judge may engage in political activity consistent with the judge’s status as a public official."[47]

The full text of the North Carolina Code of Judicial Conduct can be found here.

Removal of judges

Judges in North Carolina may be removed in one of three ways:

- Impeachment by the house of representatives and conviction by a two-thirds vote of the senate.

- In case of mental or physical incapacity, by joint resolution of two thirds of the members of each house of the general assembly.

- By the supreme court, on the recommendation of the judicial standards commission. (The supreme court may choose to merely censure the judge.)[48]

History of the court

Some of the earliest courts in North Carolina served under British rule in the late 1600s, when King Charles II of Great Britain gave eight noblemen authority over the Carolinas, and authorized them to create provincial courts. Appeals from these courts were heard by courts in England until the revolution. A general court that served as a trial court was established in North Carolina by the governor of Albemarle in 1680.[49]

North Carolina's 1776 statehood constitution created a supreme court with three judges serving for life, with good behavior. Judges were appointed by the general assembly through joint ballots. The court did not have appellate jurisdiction, but instead served as a trial court, thus functioning as a superior court with three circuit court judges, rather than a supreme court.[50]

Beginning in 1799 three superior court judges were required to meet twice yearly in Raleigh to resolve conflicting rulings as the "court of conference." In 1805, this court became the state's supreme court. It was given jurisdiction to hear appeals in 1810. In 1818 the legislature clarified that the supreme court was primarily for appeals, while superior circuit courts were for trials and other matters of original jurisdiction. Justices were appointed by the general assembly.[51]

The state's Reconstruction constitution of 1868 provided for a chief justice and four associate justices. The judges were called justices for the first time. Justices were elected by voters, instead of appointed, for eight-year terms. A 1936 constitutional amendment, the North Carolina Number of Supreme Court Justices Amendment (1936) authorized the legislature to increase the number of associate justices from four to six. In 1937 the legislature appointed two more justices, bringing the number of justices to seven, where it has remained.[52]

In 1962 North Carolina voters passed the North Carolina Judiciary Organization Amendment (1962) that substantially reformed the judiciary. It was a result of the 1955-1963 study by the "Bell Commission," led by J. Spencer Bell that provided for a unified court system, with uniform jurisdiction throughout the state. It centralized administration and budgeting with the state and created the administrative office of the courts under the chief justice. The report also resulted in the creation of the court of appeals in 1967 by the state general assembly. Prior to its creation, cases could be appealed from the superior court directly to the supreme court, taking up a considerable amount of the supreme court's time. This court was created to help relieve that burden.[53][54]

The state's 1971 constitution made no substantive changes to the judiciary since it had just gone through the major reforms a few years earlier. Justices are elected in statewide partisan elections. The general assembly is authorized to increase the size of the supreme court by two justices if it chooses.[55]

Notable firsts

Susie Sharp was the first woman to serve as chief justice of the court. She began serving on the court in 1962 and held the position of chief justice between January 1975 and July 1979.[56]

Courts in North Carolina

- See also: Courts in North Carolina

In North Carolina, there are three federal district courts, a state supreme court, a state court of appeals, and trial courts with both general and subject matter jurisdiction.

Click a link for information about that court type.

The image below depicts the flow of cases through North Carolina's state court system. Cases typically originate in the trial courts and can be appealed to courts higher up in the system.

Party control of North Carolina state government

A state government trifecta is a term that describes single-party government, when one political party holds the governor's office and has majorities in both chambers of the legislature in a state government. A state supreme court plays a role in the checks and balances system of a state government.

North Carolina has a divided government where neither party holds a trifecta. The Democratic Party controls the office of governor, while the Republican Party controls both chambers of the state legislature.

North Carolina Party Control: 1992-2025

Fourteen years of Democratic trifectas • Four years of Republican trifectas

Scroll left and right on the table below to view more years.

| Year | 92 | 93 | 94 | 95 | 96 | 97 | 98 | 99 | 00 | 01 | 02 | 03 | 04 | 05 | 06 | 07 | 08 | 09 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Governor | R | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | R | R | R | R | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D |

| Senate | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R |

| House | D | D | D | R | R | R | R | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R |

See also

External links

- North Carolina Judicial Branch

- North Carolina Judicial Branch | Supreme Court

- North Carolina Judicial Branch | Supreme Court Opinions

Footnotes

- ↑ The salary of the chief justice may be higher than an associate justice.

- ↑ North Carolina Judicial Branch, "History of the Justice Building," accessed September 20, 2021

- ↑ North Carolina Judicial Branch, "North Carolina Rules of Appellate Procedure," January 14, 2021

- ↑ nc.gov,"Judicial Branch," accessed June 23, 2024

- ↑ North Carolina Legislature,"Article 5. Review and Enforcement of Orders," accessed June 23, 2024

- ↑ Oxford University Press,"The North Carolina State Constitution," accessed June 23, 2024

- ↑ Oxford University Press,"The North Carolina State Constitution," accessed June 23, 2024

- ↑ Note: This text is quoted verbatim from the original source. Any inconsistencies are attributable to the original source.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill | School of Government, "History of North Carolina Judicial Elections," August 2020

- ↑ North Carolina Judicial Branch, "Judicial Qualifications Summary," September 28, 2016

- ↑ National Center for State Courts, "Methods of Judicial Selection: North Carolina," accessed September 20, 2021

- ↑ Ballotpedia Election Administration Legislation Tracker, "North Carolina S382," accessed December 19, 2024

- ↑ North Carolina General Assembly, "North Carolina Constitution - Article IV," accessed September 20, 2021 (Section 19)

- ↑ University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill | School of Government, "History of North Carolina Judicial Elections," accessed September 20, 2021

- ↑ General Assembly of North Carolina, "House Bill 222 / S.L. 2015-66," accessed March 7, 2016

- ↑ Ballot Access News, "North Carolina State Court Invalidates New Law Providing for Retention Elections for State Supreme Court Justices," March 4, 2016

- ↑ General Assembly of North Carolina, "North Carolina State Constitution," accessed March 7, 2016

- ↑ The News & Observer, "New uncertainties about NC Supreme Court elections," archived March 24, 2016

- ↑ WRAL, "Divided Supreme Court means no retention elections in NC for now," May 6, 2016

- ↑ North Carolina Judicial Branch, "North Carolina Judicial Branch Annual Reports," accessed October 6, 2022

- ↑ An Indeterminate score indicates that there is either not enough information about the justice’s partisan affiliations or that our research found conflicting partisan affiliations.

- ↑ The Court Balance Score is calculated by finding the average partisan Confidence Score of all justices on a state supreme court. For example, if a state has justices on the state supreme court with Confidence Scores of 4, -2, 2, 14, -2, 3, and 4, the Court Balance is the average of those scores: 3.3. Therefore, the Confidence Score on the court is Mild Republican. The use of positive and negative numbers in presenting both Confidence Scores and Court Balance Scores should not be understood to that either a Republican or Democratic score is positive or negative. The numerical values represent their distance from zero, not whether one score is better or worse than another.

- ↑ Stanford University, "State Supreme Court Ideology and 'New Style' Judicial Campaigns," October 31, 2012

- ↑ All About Redistricting, "NC League of Conservation Voters v. Hall," accessed December 9, 2021

- ↑ North Carolina Supreme Court, "Order," accessed December 9, 2021

- ↑ All About Redistricting, "Order on Plaintiffs Motion for Preliminary Injunction," December 3, 2021

- ↑ All About Redistricting, "Order," December 6, 2021

- ↑ All About Redistricting, "Order," December 6, 2021

- ↑ Fox 8, "North Carolina redistricting maps can stand, court rules, but appeals expected," January 11, 2022

- ↑ Politico, "North Carolina League of Conservation Voters, Common Cause, Harper v. Hall," accessed January 12, 2022

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 North Carolina Courts, "Harper v. Hall," accessed February 7, 2022

- ↑ WRAL, "Former judges chosen to review new election maps in NC redistricting case," February 16, 2022

- ↑ The Charlotte Observer, "Order on Remedial Plans," February 23, 2022

- ↑ The Supreme Court of North Carolina, "Harper, et al. v. Hall, et al.," December 16, 2022

- ↑ The Carolina journal, "Legislative leaders ask NC Supreme Court to rehear redistricting case," January 20, 2023

- ↑ Politico, "North Carolina Supreme Court set to rehear election cases," February 6, 2023

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 U.S. Supreme Court, “Moore, in his Official Capacity as Speaker of The North Carolina House of Representatives, et al. v. Harper et al.," "Certiorari to the Supreme Court of North Carolina,” accessed June 27, 2023

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 All About Redistricting, "Order and Judgment on Remand from the North Carolina Supreme Court," February 11, 2018

- ↑ North Carolina Judicial Branch, "Dickson et al. v. Rucho et al.," December 19, 2014

- ↑ Supreme Court of the United States, "No. 14-839," accessed September 20, 2021

- ↑ Google Scholar, "Dickson v. Rucho, 135 S. Ct. 1843 - Supreme Court 2015," April 20, 2015

- ↑ North Carolina Judicial Branch, "Dickson v. Rucho," December 18, 2015

- ↑ Supreme Court of the United States, "No. 16-24," accessed September 20, 2021

- ↑ Google Scholar, "Dickson v. Rucho, 137 S. Ct. 2186 - Supreme Court 2017," May 30, 2017

- ↑ Google Scholar, "Dickson v. Rucho, 804 SE 2d 184 - NC: Supreme Court 2017," September 28, 2017

- ↑ Brennan Center for Justice, "Dickson v. Rucho," January 4, 2019

- ↑ The North Carolina Court System, "Order Adopting Amendments to the North Carolina Code of Judicial Conduct," January 2006

- ↑ National Center for State Courts, "Methods of Judicial Selection: Removal of judges," accessed June 12, 2015

- ↑ North Carolina Courts,"The History of North Carolina Courts," accessed June 23, 2024

- ↑ North Carolina Digital Collections,"History of the Supreme Court of North Carolina," accessed June 23, 2024

- ↑ North Carolina Courts,"The History of North Carolina Courts," accessed June 23, 2024

- ↑ North Carolina Digital Collections,"History of the Supreme Court of North Carolina," accessed June 23, 2024

- ↑ North Carolina Historical Review,"The Supreme Court of North Carolina: A Brief History," accessed June 23, 2024

- ↑ North Carolina Digital Collections,"History of the Supreme Court of North Carolina," accessed June 23, 2024

- ↑ Carolana,"North Carolina - Analysis of the 1971 Constitution," accessed June 23, 2024

- ↑ North Carolina Supreme Court Historical Society, "Justices of the Court," archived February 17, 2015

Federal courts:

Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals • U.S. District Court: Eastern District of North Carolina, Middle District of North Carolina, Western District of North Carolina • U.S. Bankruptcy Court: Eastern District of North Carolina, Middle District of North Carolina, Western District of North Carolina

State courts:

Supreme Court of North Carolina • North Carolina Court of Appeals • North Carolina Superior Courts • North Carolina District Courts

State resources:

Courts in North Carolina • North Carolina judicial elections • Judicial selection in North Carolina

| ||||||||