Affordable Care Act

| Healthcare policy in the U.S. |

|---|

| Obamacare overview |

| Obamacare lawsuits |

| Medicare and Medicaid |

| Healthcare statistics |

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, also known as the Affordable Care Act (ACA) or Obamacare, was passed on March 21, 2010, and signed into law by President Barack Obama on March 23, 2010. The law required most individuals to obtain health insurance and required most employers to offer it. It provided tax credits and cost-sharing subsidies for individuals to purchase insurance in the individual market and provided for an expansion of Medicaid to cover childless adults earning incomes up to 138 percent of the poverty level. Insurers were prohibited from denying coverage to individuals with pre-existing conditions, were required to offer a standard set of benefits, and were limited in the ways they could vary their premiums.[1]

This page provides a summary of the Affordable Care Act as it was written and provides information on legislation attempting to change or repeal the law, as well as on lawsuits related to the law. See the section summaries below for a brief description of the information contained in each section. Click on the section titles to be taken to that part of the article.

- Congressional passage: This section outlines the votes taken on the bill in the U.S. House and U.S. Senate, as well as a list of Democratic senators who voted against the ACA.

- Implementation timeline: This section provides a timeline of implementation dates for major provisions of the ACA as they were written in the law.

- Summary of the law: This section provides a summary of the major components of the ACA, including the requirement to obtain insurance, the ways the law facilitated greater insurance coverage, and the requirements the law placed on health plans and insurers.

- Attempts to change or repeal: This section provides an overview of legislation and lawsuits undertaken in attempts to change or repeal parts of the law.

For more information on the impact of the ACA in each state, click here.

Congressional passage

| Federalism |

|---|

| •Key terms • Court cases •Major arguments • State responses to federal mandates • Federalism by the numbers • Index of articles about federalism |

In July 2009, House Democrats introduced the Affordable Health Care for America Act, the precursor to the Affordable Care Act. The House passed the bill on November 7, 2009, with the votes of 219 Democrats and one Republican (Rep. Joseph Cao (R-La.)). Thirty-nine Democrats and 176 Republicans voted against the bill. On December 24, 2009, the Senate passed its version of the bill 60-39, with all Democrats voting in favor of the bill and all Republicans but one voting against it (Sen. Jim Bunning (R-Ky.) was not present for the vote).[3]

In January 2010, Republican Scott Brown of Massachusetts won a special election to fill the seat of Sen. Ted Kennedy (D-Mass.), who had died in August 2009. Unless the House agreed to the Senate's version of the bill, a committee of members from the House and Senate would have to resolve differences between the two bills with a new bill that would need to receive another vote in the Senate—with the election of Brown, Senate Democrats would not have 60 votes to overcome a Republican filibuster on the new bill. A majority of the House Democratic Caucus agreed to pass the Senate bill as long as subsequent budget-related changes to the bill could be made via the reconciliation process—reconciliation bills only need 50 Senate votes to pass and are not subject to filibuster. The House passed the Senate bill on March 21, 2010, with 178 House Republicans opposing the bill's passage along with 34 Democrats, while 219 Democrats voted in favor, leaving the final vote at 219-212. The House passed the reconciliation package on the same day by a vote of 220-211 and the Senate approved the bill on March 25, 2010, by a vote of 56-43.[3][4]

President Obama signed the Senate bill on March 23, 2010, and the reconciliation bill on March 30, 2010. The two bills together are referred to as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, the Affordable Care Act, or Obamacare.[3]

Democrats in opposition

The following is a list of U.S. House Democrats who voted against the ACA's passage during the March 21, 2010 vote:[5]

- Bobby Bright (D-AL)

- Artur Davis (D-AL) -Co-Sponsor

- Robert Berry (D-AR)

- Mike Ross (D-AR)

- Jim Marshall (D-GA)

- John Barrow (D-GA)

- Walter Minnick (D-ID) -Co-Sponsor

- Daniel Lipinski (D-IL)

- Ben Chandler (D-KY)

- Charlie Melancon (D-LA)

- Frank Kratovil (D-MD)

- Stephen Lynch (D-MA)

- Collin Peterson (D-MN)

- Travis Childers (D-MS)

- Gene Taylor (D-MS)

- Ike Skelton (D-MO) -Co-Sponsor

- John Adler (D-NJ)

- Harry Teague (D-NM)

- Michael E. McMahon (D-NY)

- Michael Arcuri (D-NY)

- Mike McIntyre (D-NC)

- Larry Kissell (D-NC)

- Heath Shuler (D-NC)

- Zack Space (D-OH)

- Dan Boren (D-OK)

- Jason Altmire (D-PA)

- Tim Holden (D-PA)

- Stephanie Herseth Sandlin (D-SD)

- Lincoln Davis (D-TN)

- John Tanner (D-TN)

- Chet Edwards (D-TX)

- Jim Matheson (D-UT)

- Glenn Nye (D-VA)

- Rick Boucher (D-VA)

Implementation timeline

The following is a timeline of the implementation dates of key aspects of the Affordable Care Act. Some of the dates were later changed or delayed; these changes are not reflected in this timeline.[6]

2010

- January 1: The federal government begins providing tax credits for small businesses offering health insurance to employees.

- July 1: The Temporary Pre-existing Condition Insurance Plan is established, offered by either the federal government or individual state governments. The program provides coverage for individuals with pre-existing conditions until 2014.

- July 1: Deadline for HealthCare.gov to be established as a minimally functioning website to educate consumers on coverage options.

- July 1: The federal government begins collecting a 10 percent excise tax on indoor tanning services

- September 23: The requirement for insurers to allow adult children to remain on a parent's health insurance plan until age 26 begins

- September 23: Insurance plans are prohibited from setting lifetime coverage limitations.

- September 23: The requirement for insurers to allow appeals with an external review process begins.

- September 23: New plans established after this date are required to cover a standard set of health benefits (the 10 essential health benefits).

2011

- January 1: The requirement for insurers to provide rebate each year if a minimum proportion of premiums was not spent on medical services begins.

- January 1: Health savings accounts may no longer be used for certain purposes.

- March 23: The first round of grants are provided to states for the establishment of health insurance exchanges.

2012

- September 23: The requirement for all insurers to provide a uniform summary of care and benefits to consumers begins.

2013

- January 1: Deadline for states to notify the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services whether they will form their own exchanges or join the federal exchange.

- July 1: Deadline for grants and loans to be awarded to start-up co-ops, nonprofit, member-run health insurance companies designed by the ACA.

2014

- January 1: States begin to be allowed to expand Medicaid coverage to childless adults under 65 earning incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level.

- January 1: Deadline for individuals to obtain health insurance to avoid paying a tax penalty.

- January 1: Insurance companies no longer allowed to place annual limits on the amount they pay out for benefits.

- March 31: Months spend without health insurance begin to be counted toward the tax penalty.

2015

- January 1: Employers with more than 100 employees assessed fees, per employee, for not providing health insurance options

2016

- January 1: Employers with 50-99 employees assessed fees, per employee, for not providing health insurance options

Summary of the law

According to HealthCare.gov, the official website for the Affordable Care Act, the law had three primary goals:

| “ |

|

” |

| —HealthCare.gov[8] | ||

This section provides a summary of the major components of the ACA:

- the requirement for individuals to obtain health coverage and employers to offer it

- the law's facilitation of greater health insurance coverage through co-ops and health insurance exchanges

- the requirements the law placed on health plans and insurers

- the Medicaid expansion

- changes to Medicare reimbursements and coverage

- taxes and fees

Health coverage requirements

Individual mandate

The law required every individual to obtain health insurance and established fines for those who did not. The fines were designed to be based on the number of months a person went without health insurance in a given year and to increase each year from 2014 to 2016. The fine schedule was written as follows:[3][9]

- 2014: maximum of $95 or 1 percent of income, whichever is greater

- 2015: maximum of $325 or 2 percent of income, whichever is greater

- 2016 and thereafter: maximum of $695 or 2.5 percent of income, whichever is greater

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) was given responsibility for collecting the fine, assessed annually as a tax penalty during the income tax filing period. The law established a hardship exemption from the fine for individuals who meet certain qualifications—such as being homeless, being a victim of domestic violence, or filing for bankruptcy.[10]

Employer mandate

Under the law, medium-sized and large employers could incur fines for not offering affordable health coverage or not offering coverage at all. The law defined affordable as costing employees less than 9.69 percent of their gross household income in premiums. The law established requirements for employers with at least 50 employees to offer affordable coverage that covers at least 60 percent of costs to at least 95 percent of their workforce. If an employer does not meet these conditions and has at least one employee claim a tax credit to purchase coverage on the exchange, a fine would be incurred. The fine for not offering coverage at all was set at $2,000 per employee. The fine for not offering affordable coverage was set at $3,000 per employee. These fines were indexed to rise with inflation and in 2017 amounted to $2,260 and $3,390, respectively.[11][12]

Purchasing health insurance

Health insurance exchanges

Overview

The Affordable Care Act provided for the creation of health insurance exchanges, sometimes referred to as marketplaces, to act as a hub for consumers to browse and purchase health plans. The exchanges were designed to be accessible via websites, call centers, or in person. The law gave states three options regarding the exchanges:[13][14]

- Establish and manage their own state exchange (state-based exchange)

- Enter into a partnership with the federal government to jointly manage an exchange (state-federal partnership exchange)

- Cede responsibility for establishing and managing an exchange to the federal government (federally facilitated exchange)

The law also allowed states to set up more than one exchange to serve residents in different areas within their borders, and multiple states could create a regional exchange. However, as of August 2017, no state had chosen those options. The majority of states, 28 of them, had federally facilitated marketplaces. Another 17 had state-based exchanges; five of these exchanges were state run while utilizing the federal platform, Healthcare.gov. Six states partnered with the federal government to run their exchanges.[13][15]

States were given grants from the federal government to support the establishment and early administration of their exchanges. A total of $5 billion was awarded in grants. The grants ended on January 1, 2015, after which any state-based exchanges were expected to be self-sustaining.[16]

Plans offered

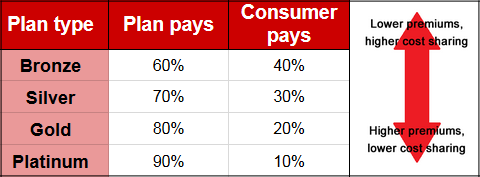

The law outlined four tiers of health coverage to be sold on the exchanges:

- bronze (lowest premiums, covers 60 percent of costs),

- silver (covers 70 percent of costs),

- gold (covers 80 percent of costs), and

- platinum (highest premiums, covers 90 percent of costs).

Plans were required to be designed and labeled under one of these four tiers to be sold on the exchanges. Just like other health plans, the portion of costs not covered by the health plan would fall to consumers.[17]

Financial assistance

The law created advanced premium tax credits—payments from the federal government to help cover the cost of premiums for those buying from the exchanges—for individuals earning incomes between 100 percent and 400 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL). In states that expanded Medicaid to adults with incomes up to 138 percent of the poverty level, eligibility for tax credits was set to begin at 139 percent of the poverty level; individuals were not allowed to be eligible for both Medicaid and health insurance subsidies. It limited the percentage of income these individuals could be required to pay towards their premiums and calculated credit amounts based on the difference between this percentage and the full premium cost for a benchmark plan. The percentage of income households must pay was indexed to change each year based on premium growth as compared to income growth. Consumers were given the choice to have their tax credits be paid directly to insurance companies on a monthly basis or claim the total credit on an annual basis when filing taxes.

The ACA also established a reduction in cost-sharing responsibilities for individuals earning incomes between 100 percent and 250 percent of the FPL, meaning they could enroll in silver plans that cover up to 94 percent of their costs. The law restricted eligibility for tax credits and cost-sharing reductions to individuals who purchase a health plan through an exchange.[18][19][20][21]

For 2017, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services used 2016 poverty guidelines to determine tax credit and cost-sharing eligibility:[19][22][23]

- The federal poverty level amounted to $11,880 for individuals and $24,300 for families of four.

- For individuals, 138 percent of the FPL amounted to $16,394, while 400 percent amounted to $47,520.

- For a family of four, 138 percent of the FPL amounted to $33,534, while 400 percent amounted to $97,200.

- Incomes that were 250 percent of the FPL amounted to $29,700 for individuals and $60,750 for a family of four.

The law did not make tax credits available for individuals below the poverty level. Childless adults who (1) reside in a state that did not expand Medicaid and (2) earn incomes between their state's Medicaid eligibility threshold and the poverty level could still buy insurance on the exchanges, but would not receive tax credits. Click 'show' on the tables below to view complete data on 2016 incomes and the 2017 maximum monthly premium paid for a benchmark plan by poverty level percentage, up to a family of four.[24]

| Incomes as percentage of 2016 federal poverty level | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household size | 100% FPL | 138% FPL | 200% FPL | 250% FPL | 300% FPL | 400% FPL | ||

| 1 | $11,880 | $16,394 | $23,760 | $29,700 | $35,640 | $47,520 | ||

| 2 | $16,020 | $22,108 | $32,040 | $40,050 | $48,060 | $64,080 | ||

| 3 | $20,160 | $27,821 | $40,320 | $50,400 | $60,480 | $80,640 | ||

| 4 | $24,300 | $33,534 | $48,600 | $60,750 | $72,900 | $97,200 | ||

| Source: Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, "Computations for the 2016 Poverty Guidelines" Amounts above 100 percent FPL calculated by Ballotpedia. | ||||||||

| Maximum monthly premium paid for 2017 benchmark plan by household size and income level | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household size | 100% FPL | 138% FPL | 200% FPL | 250% FPL | 300% FPL | 400% FPL | ||

| 2.04% of income | 3.06% of income | 6.43% of income | 8.21% of income | 9.69% of income | 9.69% of income | |||

| 1 | $20 | $42 | $127 | $203 | $288 | $384 | ||

| 2 | $27 | $56 | $172 | $274 | $388 | $517 | ||

| 3 | $34 | $71 | $216 | $345 | $488 | $651 | ||

| 4 | $41 | $86 | $260 | $416 | $589 | $785 | ||

| Source: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, "Explaining Health Care Reform: Questions About Health Insurance Subsidies" Amounts calculated by Ballotpedia and rounded to nearest dollar. The above amounts are the maximum that would be paid for a second-lowest cost silver plan, called benchmark plans; if the total monthly premium falls below the maximum amount, no tax credit is provided. Otherwise, the tax credit would equal the difference between the above figures and the total monthly benchmark premium and could be applied to other plans and metal levels. Actual amounts paid would be different if a plan on a different metal level was selected. | ||||||||

Co-ops

The Affordable Care Act designed a program for the creation of nonprofit health insurance companies called Consumer Operated and Oriented Plans, or co-ops for short. The law provided federal loans for the start-up of co-op insurance companies and outlined a series of regulations for their operation. The controlling board of a co-op was to include members enrolled in health plans through the company in order to act as a voice for enrollees. The law also stipulated that no representative from an insurance company or association could serve on the co-op boards.[25]

Co-ops could sell individual and small group insurance plans on or off the health insurance exchanges (described below). The co-ops were not allowed to accept investment income and could only sell one-third of their plans in the large group employer market. Any profits would be reinvested back into the company. Out of 23 co-ops that were created under the law, four remained in operation as of August 2017.[25]

Requirements for health plans and insurers

Coverage

The Affordable Care Act prohibited individual market insurers from denying coverage to people with pre-existing conditions. This policy is known as guaranteed issue. Guaranteed issue regulations had already existed for insurers selling employer-sponsored health plans, and the ACA extended this rule to the individual market as well.[26]

The law also required insurers to allow young adults to stay on their parents' health insurance plans until age 26. Insurers were also required to allow people in the individual market to renew their health plans each year unless they did not pay their premiums.[26]

Benefits

The ACA required individual and small group health plans that were offered both on and off the exchanges to cover services that fall into 10 broad benefits categories, called essential health benefits:[27]

- Ambulatory patient services

- Emergency services

- Hospitalization

- Maternity and newborn care

- Rehabilitative and habilitative services and devices

- Prescription drugs

- Mental health and substance use disorder services, including behavioral health treatment

- Laboratory services

- Preventive and wellness services and chronic disease management

- Pediatric services, including oral and vision care

The exact services covered were selected by each state according to the needs of its citizens; the only requirement was that covered benefits fall into each of the 10 broad categories listed above. All health plans were required to cover 100 percent of the cost of preventive services, such as screenings, as long as the physician providing the service was in the insurance plan's network. All health plans were also required to cover contraception and services related to breastfeeding.[27][28][29]

Premiums

The ACA placed restrictions on the way individual and small group insurers set a plan's premium:

- Premiums were not allowed to vary due to an individual's health status or a pre-existing condition.

- Premiums were not allowed to vary due to characteristics such as gender.

- Premiums for older individuals were not allowed to be more than three times higher than those for younger individuals.

- Premiums for tobacco users were not allowed to be more than 1.5 times higher than for non-tobacco users.

The law did not place limits on premium variation due to geographic location or the number of individuals covered by a plan. The law prohibited annual and lifetime limits on the amount insurers will pay out for covered benefits. Additionally, if individuals miss premium payments, insurers were required to allow that person to retain coverage for three months, although insurers only had to pay doctors for one month. If the premium amount was not paid during that time, then coverage could be terminated.[26][28][30][31][32]

The law established a program for reviewing insurance premium rate increases. If a state decided to administer its own program, it was required to meet minimum standards outlined by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). HHS was given the authority to review state programs, and if they did not meet the standards, federal regulators could take over the rate review process for that state. States could also cede rate review responsibility to HHS. Insurers were required to submit proposed rate increases of 10 percent or more to either state or federal regulators, whichever was applicable, for review, along with data supporting the increase. The secretary of health and human services was not granted the authority to reject premium increases; however, many state laws allow state regulators to reject or amend premium requests.[33]

Medical loss ratio

A medical loss ratio (MLR) is the portion of premium revenue that insurers spend on claims, medical care and healthcare quality for their customers. The remaining revenue typically goes toward overhead costs, such as administration, marketing and employee salaries, and then to profit. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) placed new regulations on insurers' medical loss ratios by limiting the portion of revenue that goes toward overhead and profit: individual and small group insurers were required to maintain a minimum medical loss ratio of 80 percent, while large group insurers were required to maintain a minimum MLR of 85 percent. This means at least 80 or 85 percent of premium revenue were required be used to pay customer claims and support improvements in health and healthcare quality, such as wellness promotion programs.[34][35][36]

Each year, insurers were required to publicly report their medical loss ratio and other financial information for each state and market segment. If their MLR falls below 80 percent or 85 percent, they would be required to notify their customers and provide a rebate the following year. The law exempted insurers serving fewer than 1,000 individuals in a state.[34][36]

Stabilization programs

The Affordable Care Act outlined three federal programs that were meant to stabilize the individual market during the first few years of the law and prevent premiums from rising too quickly as insurers adjusted to the new regulations:[37]

- Permanent risk adjustment required all individual and small group insurers with relatively lower risk to make payments to individual and small group insurers with relatively higher risk. The program was meant to stabilize the market by spreading financial risk. The law did not give this program an expiration date.

- Temporary risk corridors limited the losses and profits of insurers in the reformed individual market by requiring insurers with lower-than-expected costs to make payments to the federal government. Insurers with higher-than-expected costs received payments. The program was meant to protect insurers that set inaccurate premiums for the initial years of the exchanges and only applied to insurers selling plans on the exchanges. This program was set to expire in 2017. On June 14, 2018, a federal appellate court ruled that the federal government did not have to make payments to insurers under the risk corridor program. The suit was brought by two health insurers, Moda Health and Land of Lincoln. The court ruled 2 to 1 that the federal government did not have to make risk corridor payments because Congress took action after the enactment of Obamacare to ensure that the program remained budget neutral from year to year.[38]

- Transitional reinsurance required most health insurers (individual, small group, and large group) to pay a fee to the federal government based on their enrollment figures for a plan year. The fee went toward payments to insurers on the individual market that covered high-cost individuals. The program was meant to keep premiums low by offsetting the cost of care for individuals with complex conditions. This program was set to expire in 2016.

Medicaid

- See also: Medicaid spending by state

Eligibility expansion

The Affordable Care Act expanded eligibility for Medicaid to more individuals. Medicaid was originally limited to pregnant women and young children with household incomes around the federal poverty level, and to disabled people, older children, and parents with household incomes below the federal poverty level. Each state was allowed to decide whether to also cover able-bodied adults without children or people with slightly higher incomes, though they were previously required to obtain a federal waiver to do this.[39]

The ACA provided for the expansion of Medicaid eligibility to cover childless adults whose income amounted to 138 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) or below. In 2017, this amounted to $16,643 for individuals and $33,948 for a family of four. Although the law originally required states to expand their Medicaid programs or lose federal Medicaid funding, in 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the federal government could not condition Medicaid funding on an expansion of the program. The ruling essentially made participation in the expansion voluntary on the part of the states.[3][40]

The provision for expanding Medicaid went into effect nationwide in 2014. The federal government provided 100 percent of funding to cover newly eligible enrollees through 2016, dropping this funding level to 95 percent in 2017 and to 90 percent in 2020 and thereafter. The law did not provide for tax credits for adults with household incomes lower than the federal poverty level, because the law had intended to cover these people under Medicaid. In states that didn't expand Medicaid, these adults neither qualified for Medicaid nor for federal tax credits to purchase health insurance.[41][42]

As of January 2022, a total of 38 states and Washington, D.C., had expanded or voted to expand Medicaid, while 12 states had not. The map below provides information on Medicaid expansions by state; for states that expanded, hover over the state to view the political affiliation of the governor at the time of expansion.[43]

Other provisions

The Affordable Care Act enacted a temporary increase for Medicaid's reimbursements to primary care physicians, matching Medicare levels during 2013 and 2014. The law provided states with federal funding for the purpose. States were not required to maintain the higher reimbursement rates after 2014. The law also established the requirement that states accept multiple forms of enrollment applications, including online applications.[3]

Medicare

Spending and revenues

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) included changes to Medicare reimbursements and the premiums that beneficiaries pay. The law reduced reimbursements to private Medicare Advantage plans, which are health plans for Medicare beneficiaries administered by private insurers and financed by the federal government. The change was expected to reduce Medicare spending by $132 billion between 2010 and 2020. The law also reduced payments to healthcare providers.[44][45]

In addition, prior to the ACA, Medicare required beneficiaries at a certain level of income to pay higher monthly premiums for coverage. The income threshold was indexed to increase annually with inflation. The ACA suspended this indexing through 2019, meaning over time, more beneficiaries would be required to pay the higher premiums. The ACA also required higher-income beneficiaries to begin paying higher premiums for prescription drug coverage.[45]

Independent Payment Advisory Board

The law established a new government agency called the Independent Payment Advisory Board (IPAB). IBAP was modeled on a proposal by former senator Tom Daschle, who in turn modeled it after the Federal Reserve Board. If the projected rate of growth in Medicare spending exceeded a target amount, IPAB would be required to craft a proposal to reduce Medicare spending. IPAB's decisions would be binding and would require a three-fifths super-majority from Congress in order to be overturned. The Department of Health and Human Services would automatically implement its recommendations unless overridden by Congress. However, the law stipulated that IPAB could not ration healthcare, raise premiums or restrict eligibility.[46]

Writing in the Wall Street Journal, Sarah Palin argued that the Affordable Care Act "implicitly endorses the use of 'death panel'-like rationing by way of the new Independent Payments Advisory Board—making bureaucrats, not medical professionals, the ultimate arbiters of what types of treatment will (and especially will not) be reimbursed under Medicare." As of 2017, the IPAB had not been created.[47][48]

Medicare prescription drug coverage

The law closed the doughnut hole of Medicare prescription drug coverage (Part D). Previously, Medicare would cover prescription drug costs up to $2,250 in a given year, after which beneficiaries were responsible for 100 percent of their prescription drug costs until they hit $5,100 that year. The ACA established coverage for a portion of the costs for drug spending in this range.[3]

Payment models

The ACA outlined a pilot program to test the effect of bundled payments for Medicare. A bundled payment is the delivery of one single payment to providers for the entire range of services used to treat a condition. By contrast, under traditional fee-for-service reimbursement, doctors are paid separately for each service provided. For the Medicare program, the law allowed providers to voluntarily group together to enter into the payment arrangement with Medicares.[26][49][50]

The ACA also included a shift from volume-based purchasing—paying for the number of services provided—to value-based purchasing—paying for the quality of services provided. Since 2012, hospitals have received a 1 percent reduction in Medicare payments to fund a reward program providing bonuses to hospitals that meet standards of high quality, efficient care.[26][51]

Additionally, the law included four provisions related to primary care:[26][52]

- Extra funding for the National Health Service Corps, which provides scholarships and loan repayment for primary care providers serving in high-need communities

- Extra funding for programs that train primary care providers

- A 10 percent increase in Medicare payments to primary care providers through 2015

- An increase in Medicaid payments to primary care providers to Medicare levels through 2014

Accountable care organizations

The Affordable Care Act included provisions outlining a system of accountable care organizations (ACOs) as a model for Medicare providers. An accountable care organization (ACO) is a group of doctors, hospitals, or other healthcare providers that work together with the stated purpose of delivering high-quality care at a lower cost. The formation of ACOs was made voluntary for providers. Under the model outlined by the ACA, if an ACO generated savings on the cost of care for a Medicare patient, the federal government would give the providers a portion of the savings. If not, the group would have to take a loss on the cost of care provided. ACOs could be formed by physicians, hospitals or—in the private market—insurers. Although the ACO provision of the Affordable Care Act pertained specifically to Medicare, some providers formed ACOs for patients with private insurance as well, and 16 state Medicaid programs contract with ACOs. According to the journal Health Affairs, as of September 2015, the majority of the 23.5 million individuals served by ACOs were enrolled in private insurance or Medicaid. Medicare patients accounted for 7.8 million of the individuals in ACOs.[26][53][54]

Taxes and fees

The following is a list of taxes and fees included in the Affordable Care Act as written. This list may not be exhaustive and changes to the tax code in subsequent years may have impacted some of these provisions.[55]

- additional 0.9 percent Medicare tax on high-income earners

- 3.8 percent tax on investment income above a certain threshold

- 40 percent excise tax on high-cost health plans (known as the Cadillac tax)

- 10 percent excise tax on indoor tanning services

- annual fee for manufacturers of brand name pharmaceuticals

- annual fee for health insurers

- 2.3 percent excise tax on medical devices

Attempts to change or repeal

September 14, 2017: Commenting on the apparent change of position among Republican senators who voted against Obamacare repeal, Senator Ben Sasse (R-Neb.) claimed, “With just one exception, every member of the Republican majority already either voted for repeal or explicitly campaigned on repeal.”

Is Sasse correct?

Read Ballotpedia's fact check »

The Affordable Care Act was subject to a number of lawsuits challenging some of its provisions, such as the individual mandate and the requirement to cover contraception. Four of these lawsuits were heard by the United States Supreme Court, resulting in changes to the law and how it was enforced. In addition, since the law's enactment, lawmakers in Congress have introduced and considered legislation to modify or repeal parts or all of the Affordable Care Act. Finally, between 2010 and 2012, voters in eight states considered ballot measures related to the law. This section summarizes the lawsuits, legislation, and state ballot measures that attempted to change, repeal, or impact enforcement of parts of the law.

Lawsuits

- See also: Obamacare lawsuits

Zubik v. Burwell

Pursuant to the U.S. Supreme Court's 2014 decision in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby, religious organizations and closely-held for-profit companies became eligible for an exemption from the Affordable Care Act's contraception mandate. Under the exemption, organizations could notify the government of their religious objections to contraception, which would then make an arrangement with the insurance company to provide contraceptive coverage to the employees. However, 43 different Catholic organizations filed 12 lawsuits challenging this accommodation, arguing that they would still be complicit in providing contraception to their employees. Read more.

King v. Burwell

The Affordable Care Act states an individual is eligible for a tax credit if he or she enrolls in an insurance plan through "an Exchange established by the State." Consequently, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) issued a rule allowing tax credits for insurance plans purchased in both state and federal exchanges. At issue in King v. Burwell was whether the ACA permitted the IRS to interpret the law in this way and grant tax credits to individuals who purchased their health insurance from the federal health insurance exchange in addition to the state exchanges. If tax subsidies were not available for insurance plans purchased through federal exchange, an estimated 6.4 million Americans would have been impacted, and the three interconnected reforms of Obamacare would have been undermined. Read more.

National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius

This federal lawsuit was filed in Florida, with 26 states, two individuals, and an independent organization named as plaintiffs. The lawsuit challenged the Affordable Care Act on the grounds that the individual health insurance mandate exceeded Congress' authority to regulate interstate commerce under the Commerce Clause of Article I and did not fall within its power to tax. The complaint further alleged that the Act violated the Tenth Amendment by compelling states to follow federal regulations—under the ACA, states would have lost federal Medicaid funding had they not expanded their Medicaid programs. Read more.

Burwell v. Hobby Lobby

The Affordable Care Act had mandated that insurance plans must cover certain essential benefits—which HHS later interpreted to include contraceptive coverage. Employers that didn't provide this benefit in their health insurance plan would face hefty fines. Two family-owned companies—Hobby Lobby and Conestoga Wood Specialty—challenged the contraception mandate in court. They sought exemptions from coverage of four different contraceptives—two emergency morning after pills and two intrauterine devices (IUDs)—on the basis that those contraceptives were forms of abortion according to their religious beliefs. Read more.

U.S. House of Representatives v. Burwell

On July 30, 2014, the House voted 225 to 201 in favor of a resolution to file a lawsuit against the Obama administration. The lawsuit challenged the administration's delay of the ACA's employer mandate and its payment of subsidies to insurers for providing a reduced cost burden to low-income consumers under the law. Boehner claimed the executive branch "changed the healthcare law without a vote of Congress" by delaying the employer mandate and violated Article I of the Constitution by using unappropriated funds to make payments to insurers. Read more.

Legislation

According to the Congressional Research Service, up through December 2015, the U.S. House of Representatives voted to alter, defund, delay, or repeal portions of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in some way 56 times before. Sixteen of these measures were ultimately enacted and signed into law by former President Barack Obama (D); these bills made bipartisan changes such as delaying the 40 percent excise tax on high-cost health plans and amending definitions.[56]

Four of the bills that passed the House would have repealed the law in its entirety had they been enacted; only one made it to President Obama's desk, HR 3762. The passage of HR 3762, the Restoring Americans' Healthcare Freedom Act, marked the first time a measure to repeal major portions of the law had passed both the House and the U.S. Senate. President Obama vetoed the bill.[56][57]

In 2017, following the election of President Donald Trump (R), Congress voted on two bills to modify the ACA, the American Health Care Act (AHCA) in the House and the Better Care Reconciliation Act (BCRA) in the Senate. Both bills were reconciliation bills that proposed modifying the budgetary and fiscal provisions of the ACA. The House passed the AHCA 217-213 on May 4, 2017. During the week of July 23, 2017, the Senate held a series of votes on the BCRA. Ultimately, the Senate did not pass the bill.

American Health Care Act of 2017

- See also: American Health Care Act of 2017

On March 6, 2017, House Republicans introduced the American Health Care Act of 2017 (AHCA), a reconciliation bill that proposed modifying the budgetary and fiscal provisions of the ACA. Trump offered his full support for the legislation.[58][59]

The bill was a reconciliation bill, meaning it would have impacted the budgetary and fiscal provisions of the ACA, and did not contain a provision to repeal the law in its entirety. It proposed repealing the tax penalties on individuals for not maintaining health coverage and on employers for not offering coverage. The ACA's income-based tax credits for purchasing insurance would have ended, as would have the enhanced federal funding for states that expanded Medicaid. The bill contained its own system of tax credits, based on age rather than income, and a penalty in the form of increased premiums for individuals who did not maintain continuous coverage.[58]

After two canceled votes in March, the House reintroduced the measure on April 6, 2017. On April 13, House Republicans added a new amendment to the American Health Care Act in an attempt to unite the party behind the bill, allowing states to opt out of some of the bill's provisions. Another amendment was added on May 3, 2017, to provide states with an additional $8 billion over five years to fund high-risk pools. These two amendments garnered enough votes from moderate and conservative Republicans to pass the bill on May 4, 2017, by a vote of 217-213.[60][61][62]

Better Care Reconciliation Act of 2017

- See also: Better Care Reconciliation Act of 2017

On June 22, 2017, the U.S. Senate released the Better Care Reconciliation Act of 2017 (BCRA), its version of the House bill, the American Health Care Act (AHCA). The bill was a reconciliation bill that proposed modifying the budgetary and fiscal provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), also known as Obamacare. On July 13, 2017, the Senate released a revised version of the bill that included changes, such as $45 billion to address the opioid epidemic and allowing the sale of health plans that do not comply with ACA standards. For detailed information on the BCRA, click here.

On July 17, 2017, after weeks of negotiating the bill, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) said that his party was unable to agree on a replacement bill for the ACA, but the bill was revived two days later. During the last week of July, the Senate voted on three major proposals to repeal and replace the ACA. A procedural vote on the BCRA was rejected by a vote of 43-57. A proposal to repeal the ACA and delay the effective date for two years to provide time for a replacement bill failed by a vote of 45-55. The final major amendment—the "skinny bill"—was rejected by a 49-51 vote. It contained the provisions to repeal the requirements for individuals to enroll in health insurance and for employers to offer it, among other provisions.[63][64][65][66][67]

After the skinny bill failed, McConnell said, “it is time to move on,” and he called the final defeat disappointing.[68]

Restoring Americans' Healthcare Freedom Act of 2015

On January 6, 2016, the U.S. House of Representatives voted in favor of a bill to repeal parts of the Affordable Care Act, also known as "Obamacare," and to end federal funding for Planned Parenthood over the next year. President Barack Obama vetoed the measure on January 8, stating that the legislation would have caused harm "to the health and financial security of millions of Americans."[57]

The bill, HR 3762, was widely expected to be vetoed by the president and, according to The Hill, was viewed as more of a symbolic move for the Republican Party to show voters "how they would govern if they win back the White House in November." The measure had been passed earlier in the Senate as a reconciliation bill, which bypasses filibuster attempts and needs only 51 votes to pass, rather than the standard 60 votes. The bill would have ended the expansion of Medicaid and federal subsidies for people buying health insurance on the new exchanges. These changes would have taken place in 2018, and Republicans say they would have used the two years in between to implement a replacement of the law. The Congressional Budget Office and the Joint Committee on Taxation estimated that the bill would have reduced the federal deficit by $282 billion between 2016 and 2025.[56][69]

Ballot measure challenges

Beginning early on during congressional debate over the Affordable Care Act, 10 legislative referrals and citizen initiatives appeared seeking to stop implementation of the act in eight states. Most of these ballot measures proposed an amendment to the state's constitution declaring that citizens of the respective state could not be compelled to purchase health insurance or be fined for not doing so. Some measures, however, instead chose to focus on prohibiting the state's government from establishing a health insurance exchange. This particular tactic was used so as to gain additional legal leverage before the courts by making available the argument that the federal law violated state constitutions. Another aspect of this strategy was to demonstrate public disapproval of the bill by having such constitutional changes be decided by voters rather than state legislators. This effort was not universally successful, however, because voters in some states refused to approve these constitutional amendments.

The following is a list of states that saw such constitutional amendments on their ballots since 2008. Successful measures are indicated with a ![]() .

.

- Arizona Health Insurance Reform Amendment, Proposition 106 (2010)

- Missouri Health Care Freedom, Proposition C (August 2010)

- Oklahoma Health Care Freedom Amendment, State Question 756 (2010)

- Alabama Health Care Amendment, Amendment 6 (2012)

- Montana Health Care Measure, LR-122 (2012)

- Wyoming Health Care Amendment, Constitutional Amendment A (2012)

- Missouri Health Care Exchange Question, Proposition E (2012)

- Florida Health Care, Amendment 1 (2012)

- Arizona Medical Freedom to Choose, Proposition 101 (2008)

- Colorado Health Care, Amendment 63 (2010)

Recent news

The link below is to the most recent stories in a Google news search for the terms Affordable Care Act. These results are automatically generated from Google. Ballotpedia does not curate or endorse these articles.

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ New York Times, "Obama Signs Health Care Overhaul Bill, With a Flourish," March 23, 2010

- ↑ National Academy for State Health Policy, "Where States Stand on Medicaid Expansion," November 7, 2018

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 The Staff of The Washington Post. (2010). Landmark: The Inside Story of America's New Health-Care Law and What It Means for Us All. New York, NY: PublicAffairs.

- ↑ Congress.gov, "H.R.3590 - Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act," accessed August 28, 2017

- ↑ GovTrack, "H.R. 3590 (111th): Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act," March 21, 2010

- ↑ Kaiser Family Foundation, "Health Reform Implementation Timeline," accessed March 12, 2014

- ↑ Note: This text is quoted verbatim from the original source. Any inconsistencies are attributable to the original source.

- ↑ HealthCare.gov, "Affordable Care Act (ACA)," accessed August 17, 2017

- ↑ HealthCare.gov, "If you don't have health insurance: How much you'll pay," accessed August 21, 2017

- ↑ HealthCare.gov, "Hardship exemptions, forms & how to apply," accessed August 21, 2017

- ↑ Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, "Employer Responsibility Under the Affordable Care Act," September 30, 2016

- ↑ Internal Revenue Service, "Employer Shared Responsibility Provisions," accessed August 28, 2017

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 National Conference of State Legislatures, "State Actions to Address Health Insurance Exchanges," October 13, 2015

- ↑ Healthcare.gov, "Health Insurance Marketplace," accessed November 16, 2015

- ↑ The Staff of The Washington Post. (2010). Landmark: The Inside Story of America's New Health-Care Law and What It Means for Us All. New York, NY: PublicAffairs.

- ↑ The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, "Total Health Insurance Exchange Grants," accessed October 20, 2015

- ↑ Healthcare.gov, "Health Plan Categories," accessed November 16, 2015

- ↑ Healthcare.gov, "Advanced Premium Tax Credits (APTC)," accessed October 19, 2015

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Internal Revenue Service, "Questions and Answers on the Premium Tax Credit," accessed October 19, 2015

- ↑ The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, "Cost-Sharing Subsidies in Federal Marketplace Plans," February 11, 2015

- ↑ Healthcare.gov, "Cost Sharing Reduction," accessed October 19, 2015

- ↑ Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, "Computations for the 2016 Poverty Guidelines," accessed August 21, 2017

- ↑ Healthcare.gov, "Federal Poverty Level (FPL)," accessed October 19, 2015

- ↑ The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, "The Coverage Gap: Uninsured Poor Adults in States that Do Not Expand Medicaid – An Update," October 23, 2015

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 HealthInsurance.org, "CO-OP health plans: patients’ interests first," accessed August 23, 2017

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 26.5 26.6 Politico, "Understanding Obamacare: POLITICO's Guide to the Affordable Care Act," accessed October 21, 2015

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 HealthCare.gov, "What Marketplace health insurance plans cover," accessed August 22, 2017

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Forbes, "Essential Health Benefits Under The Affordable Care Act," October 11, 2013

- ↑ Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, "Essential Health Benefits," May 2, 2013

- ↑ United State Government Printing Office, "Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act; Health Insurance Market Rules; Rate Review," February 27, 2013

- ↑ United States Department of Health and Human Services, "Lifetime & Annual Limits," accessed October 21, 2015

- ↑ Legal Information Institute, "45 CFR 156.270 - Termination of coverage for qualified individuals," accessed October 22, 2015

- ↑ The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, "Health Insurance Market Reforms: Rate Review," December 2012

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Congressional Research Service, "Medical Loss Ratio Requirements Under the Affordable Care Act," August 26, 2014

- ↑ Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, "Medical Loss Ratio," accessed October 13, 2015

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, "Explaining Health Care Reform: Medical Loss Ratio (MLR)," February 29, 2012

- ↑ The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, "Explaining Health Care Reform: Risk Adjustment, Reinsurance, and Risk Corridors," August 17, 2016

- ↑ Politico, "Court: Federal government doesn't owe insurers Obamacare payments," June 14, 2018

- ↑ Tate, N. (2012) Obamacare Survival Guide. Humanix Books: Boca Raton, FL.

- ↑ Oyez, "National Federation of Independent Businesses v. Sebelius," accessed May 20, 2016

- ↑ The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, "Medicaid Financing: How Does it Work and What are the Implications?" May 20, 2015

- ↑ Kaiser Family Foundation, "The Coverage Gap: Uninsured Poor Adults in States That Do Not Expand Medicaid Coverage," April 17, 2015

- ↑ HealthInsurance.org, "Medicaid," accessed January 10, 2020

- ↑ Tate, N. (2012) Obamacare Survival Guide. Humanix Books: Boca Raton, FL.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Kaiser Family Foundation, "Medicare Spending and Financing: A Primer," February 2011

- ↑ Congressional Research Service, "The Independent Payment Advisory Board," April 17, 2013

- ↑ Wall Street Journal, "Why I Support the Ryan Roadmap," December 10, 2010

- ↑ Health Affairs Blog, "ACA Round-Up: Medicare Trustees Report Does Not Trigger IPAB, And More," July 14, 2017

- ↑ Health Affairs, "The Payment Reform Landscape: Bundled Payment," July 2, 2014

- ↑ Harvard Business Review, "Getting Bundled Payments Right in Health Care," October 19, 2015

- ↑ Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, "How Does Medicare Value-Based Purchasing Work?" June 2012

- ↑ United States Department of Health and Human Services, "Creating Health Care Jobs by Addressing Primary Care Workforce Needs," accessed October 22, 2015

- ↑ Kaiser Health News, "Accountable Care Organizations, Explained," September 14, 2015

- ↑ Health Affairs Blog, "Growth And Dispersion Of Accountable Care Organizations In 2015," March 31, 2015

- ↑ Internal Revenue Service, "Affordable Care Act Tax Provisions," accessed August 23, 2017

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 Congressional Research Service, "Legislative Actions to Repeal, Defund, or Delay the Affordable Care Act," December 9, 2015

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 CNN, "Obama vetoes Obamacare repeal bill," January 8, 2016

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 House Energy and Commerce Committee, "Budget Reconciliation Legislative Recommendations Relating to Repeal and Replace of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act," accessed March 7, 2017

- ↑ Breitbart, "Donald Trump: ‘I’m 100 Percent Behind’ Obamacare Replacement Plan," accessed March 22, 2017

- ↑ Reuters, "U.S. House passes healthcare bill in big win for Trump," May 4, 2017

- ↑ CNBC, "Republicans have a new plan to repeal Obamacare — and here it is," April 20, 2017

- ↑ The New York Times, "$8 Billion Deal Gives Crucial Momentum to G.O.P. Health Bill," May 3, 2017

- ↑ The Hill, "Senate GOP revives negotiation over ObamaCare repeal and replace," July 19, 2017

- ↑ Senate.gov, "On the Motion (Motion to Waive All Applicable Budgetary Discipline Re: Amdt. No. 270)," July 25, 2017

- ↑ Senate.gov, "On the Amendment (Paul Amdt. No. 271 )," July 26, 2017

- ↑ Senate.gov, "On the Amendment (McConnell Amdt. No. 667 )," July 28, 2017

- ↑ Axios, "Here’s the Senate’s “skinny” health care bill," July 27, 2017

- ↑ The Hill, "McConnell: 'Time to move on' after healthcare defeat," July 28, 2017

- ↑ The Hill, "House passes ObamaCare repeal, sending measure to president," January 6, 2016