Hydrogeology of Burundi

Africa Groundwater Atlas >> Hydrogeology by country >> Hydrogeology of Burundi

Lire cette page en français: Hydrogéologie du Burundi

One of the smallest and most densely populated countries in Africa, Burundi was an independent kingdom for over 200 years until the early 20th century. It was then colonised first by Germany, and after the First World War by Belgium, and governed with present day Rwanda as Ruanda-Urundi until independence in 1962. Initially, independent Burundi was a monarchy, but after a period of civil and military unrest the monarchy was abolished and a one-party republic established in 1966. Burundi has continued to experience multiple periods of unrest, sometimes with violence between the Hutu and Tutsi cultural groups, including two periods in which genocide was identified, first in the 1970s and then in the 1990s. Since the 1990s Burundi has had a multi-party state, but has continued to experience periods of political and military unrest, such as disrupted presidential elections and a coup attempt in 2015. Burundi left the International Criminal Court (ICC) in 2017, after the ICC initiated an investigation into potential human rights crimes by the country.

Decades of civil and military unrest has left the national infrastructure in very poor state, including water and sanitation services. The population is mostly rural and employed in subsistence agriculture, but high population density and lack of land access mean many farmers can’t support themselves. Pressure to increase agricultural land has resulted in widespread deforestation. Export earnings are also dominated by agriculture (mainly coffee and tea), but these account for only a small proportion of GDP. External aid accounts for over 40% of the national income. Burundi has resources of a number of metal minerals but to date has a relatively small mining industry, of which gold provides the biggest export income. Most of the country’s electricity is produced by hydroelectric power.

With relatively high rainfall, Burundi has relatively abundant water resources, but because rainfall and surface water are unevenly distributed both spatially and seasonally, and because water supply infrastructure is poor, there is significant pressure on water resources. Most rural communities rely on groundwater, including from numerous natural springs.

Compilers

Dr Kirsty Upton and Brighid Ó Dochartaigh, British Geological Survey, UK

Dr Imogen Bellwood-Howard, Institute of Development Studies, UK

Please cite this page as: Upton, Ó Dochartaigh and Bellwood-Howard, 2018.

Bibliographic reference: Upton K, Ó Dochartaigh B É and Bellwood-Howard, I. 2018. Africa Groundwater Atlas: Hydrogeology of Burundi. British Geological Survey. Accessed [date you accessed the information]. https://earthwise.bgs.ac.uk/index.php/Hydrogeology_of_Burundi

Terms and conditions

The Africa Groundwater Atlas is hosted by the British Geological Survey (BGS) and includes information from third party sources. Your use of information provided by this website is at your own risk. If reproducing diagrams that include third party information, please cite both the Africa Groundwater Atlas and the third party sources. Please see the Terms of use for more information.

Geographical setting

General

| Capital city | Bujumbura |

| Region | Eastern/Central Africa |

| Border countries | Rwanda, Tanzania, the Democratic Republic of the Congo |

| Total surface area* | 27,830 km2 (2,783,000 ha) |

| Total population (2015)* | 11,179,000 |

| Rural population (2015)* | 9,875,000 (88%) |

| Urban population (2015)* | 1,304,000 (12%) |

| UN Human Development Index (HDI) [highest = 1] (2014)* | 0.3999 |

* Source: FAO Aquastat

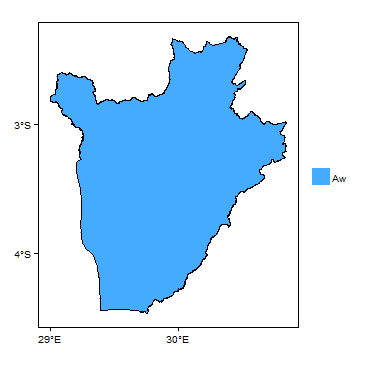

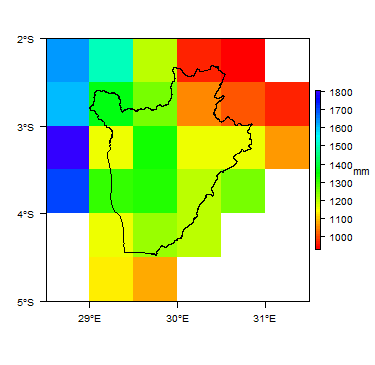

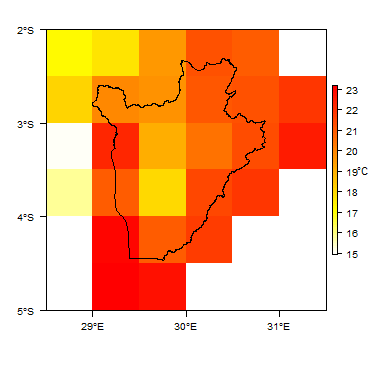

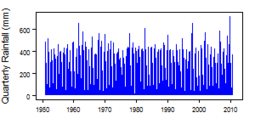

Climate

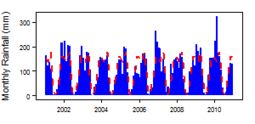

These maps and graphs were developed from the CRU TS 3.21 dataset produced by the Climatic Research Unit at the University of East Anglia, UK. For more information see the climate resource page.

Surface water

|

Burundi has relatively abundant surface water resources, because of high rainfall and storage in marshes and lakes. A dense hydrographic network means that it has a high hydroelectric potential. Among the internal rivers are the: Kaburantwa, Kagunuzi, Mpanda, Murembwe, Mugere, Mubarazi, Muhira, Mutsindosi, and Ruvubu rivers. There are also large areas of marshes, and the major lakes Cohoha and Rweru (African Development Fund 2005).

|

|

Soil

|

Land cover

|

Water statistics

| 1998 | 2000 | 2005 | 2014 | 2015 | |

| Rural population with access to safe drinking water (%) | 73.8 | ||||

| Urban population with access to safe drinking water (%) | 91.1 | ||||

| Population affected by water related disease | No data | No data | No data | No data | No data |

| Total internal renewable water resources (cubic metres/inhabitant/year) | 899.9 | ||||

| Total exploitable water resources (Million cubic metres/year) | No data | No data | No data | No data | No data |

| Freshwater withdrawal as % of total renewable water resources | 2.297 | ||||

| Total renewable groundwater (Million cubic metres/year) | 7,470 | ||||

| Exploitable: Regular renewable groundwater (Million cubic metres/year) | No data | No data | No data | No data | No data |

| Groundwater produced internally (Million cubic metres/year) | 7,470 | ||||

| Fresh groundwater withdrawal (primary and secondary) (Million cubic metres/year) | No data | No data | No data | No data | No data |

| Groundwater: entering the country (total) (Million cubic metres/year) | |||||

| Groundwater: leaving the country to other countries (total) (Million cubic metres/year) | |||||

| Industrial water withdrawal (all water sources) (Million cubic metres/year) | 15 | ||||

| Municipal water withdrawal (all water sources) (Million cubic metres/year) | 43.1 | ||||

| Agricultural water withdrawal (all water sources) (Million cubic metres/year) | 222 | ||||

| Irrigation water withdrawal (all water sources)1 (Million cubic metres/year) | 200 | ||||

| Irrigation water requirement (all water sources)1 (Million cubic metres/year) | 28.4 | ||||

| Area of permanent crops (ha) | 350,000 | ||||

| Cultivated land (arable and permanent crops) (ha) | 1,550,000 | ||||

| Total area of country cultivated (%) | 55.7 | ||||

| Area equipped for irrigation by groundwater (ha) | No data | No data | No data | No data | No data |

| Area equipped for irrigation by mixed surface water and groundwater (ha) | No data | No data | No data | No data | No data |

These statistics are sourced from FAO Aquastat. They are the most recent available information in the Aquastat database. More information on the derivation and interpretation of these statistics can be seen on the FAO Aquastat website.

Further water and related statistics can be accessed at the Aquastat Main Database.

1 More information on irrigation water use and requirement statistics

Geology

The geology map shows a simplified version of the geology at 1:5 million scale.

Download a GIS shapefile of the Burundi geology and hydrogeology map.

Some more information on the geology of Burundi is available in the report United Nations (1989) and in Schlüter (2006).

Summary

The geology of Burundi is dominated by Precambrian basement rocks, mostly of Proterozoic age.

| Key formations | Period | Lithology | |

| Unconsolidated | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Alluvium and lake sediments | Quaternary-Tertiary | Unconsolidated sediments that mainly infill the major tectonic rift valley in the west of Burundi, running down to Lake Tanganyika. These sediments comprise mainly alluvial sands, silts, gravels and clays. There are also smaller outcrops of alluvium in smaller river valleys and around lakes across the country, which are too small to be shown on this map. | |

| Volcanic rocks | |||

| Cenozoic | A small area of basaltic rocks is present in the extreme northwest of Burundi, but its outcrop is too small to be shown on the 1:5 million scale map. | ||

| Precambrian

A number of different units within the Precambrian are named, with complex outcrops across the country (e.g. see Schlüter 2006, UN 1988). These are not distinguished on this geology map because of its small scale. The main divisions are described below. | |||

| Malagarasian Supergroup | Metasedimentary rocks, largely schist and quartzite, which outcrop in a narrow strip along the southeast border with Tanzania (UN 1989). This is equivalent to the Bukoban System in northwestern Tanzania (Schlüter 2006). | ||

| Burundian Supergroup | Middle Proterozoic | Metasedimentary rocks, largely quartzite with minor amounts of intercalated schist. These Burundian rocks cover most of Burundi, including all of the centre of the country (United Nations 1989). The group is also sometimes known as the Kibaran Belt. | |

| Archean complex | Lower Proterozoic | Highly deformed metamorphic rocks, mainly gneiss, intercalated with amphibolite and quartzite. These rocks crop out only in small parts of the south and east of the country (United Nations 1989). | |

Hydrogeology

The hydrogeology map below shows a simplified version of the type and productivity of the main aquifers at 1:5 million scale (see the hydrogeology map resource page for more details).

Download a GIS shapefile of the Burundi geology and hydrogeology map.

More information on the hydrogeology of Burundi is available in these documents:

- - a number of reports from the groundwater project Management and Protection of Groundwater Resources in Burundi carried out by BGR;

- - a report by BRGM (2016) on mapping groundwater availability in basement rocks (page 64), which includes a map of groundwater potential in Burundi (see also Gutierrez and Barrat 2016 in References section, below); and

- - a report by United Nations (1989) on groundwater in Burundi.

Unconsolidated

| Aquifer Productivity | Named Aquifers and General Description | Recharge |

| Variable Productivity (Low to High) | These unconsolidated alluvial sediments have variable aquifer properties, depending largely on lithology. Where the alluvium is dominated by coarser grained deposits (gravel and coarse sand), storage capacity and transmissivity may be high. The only areas known in Burundi where alluvial sediments are thick enough to form productive aquifers are on the Moso Plain in south Burundi and Imbo Valley in west Burundi (Gutierrez and Barrat 2016). However, there may be other smaller alluvial aquifers in other smaller valleys, which have local potential. | Recharge is generally high, fed by both rainfall and close hydraulic connection with rivers and valley wetlands. |

Volcanic

| Aquifer Productivity | Named Aquifers and General Description |

| Unknown Productivity | Little or nothing is known about groundwater in the small areas of volcanic rocks in Burundi. |

Weathered, Fractured Basement

| Aquifer Productivity | Named Aquifers and General Description |

| Variable Productivity (generally Low to Moderate but sometimes High) | The productivity of the basement aquifer depends on the localised nature and extent of fracturing and weathering - how thick is the weathered zone and how developed are water-bearing fractures? A thick weathered zone - in some parts of granite and schist basement, such as at Kirundo, this can be up to 100 m (Gutierrez and Barrat 2016) - can provide significant groundwater storage potential. Where tectonic activity has caused increased rock fracturing , such as in fault zones, local basement aquifer productivity can be moderate or high. Fracturing may also, however, act to compartmentalise an aquifer and reduce groundwater flow, which can affect the long-term sustainable yield of a borehole - for example, as suggested in Gitega in central Burundi (Pfunt et al. 2016).

BGR have carried out hydrogeological studies of the basement aquifer at sites at Gitega (the second largest city in Burundi), Kirundo and Rumonge. Data from the Nyanzare wellfield at Gitega where boreholes abstract from fractured zones in the fractured schist and amphibolitic basement indicate that appropriately sited boreholes in the basement aquifer have typical transmissivity values of between 20 and 500 m2/day, possibly up to 700 m2/day (Tiberghien et al. 2014, Pfunt et al. 2016). Borehole yields of up to 60 m3/hour are reported (Gutierrez and Barrat 2016), but compartmentalisation of the aquifer by fracturing suggests that these abstraction rates are not likely to be sustainable (Pfunt et al. 2016). BGR quote transmissivity values of around 35 m2/day, and borehole yields of up to 20 m3/hour, from the weathered zone of granites at Kirundo. However, more typical borehole yields across most of the basement aquifer are likely to be lower: from around <0.5 to 5 m m3/hour (Gutierrez and Barrat 2016). Groundwater levels (water table) in the basement aquifer at Gitega are around 15 m below ground level in the base of the valley (Pfunt et al. 2016); they may be deeper at higher elevations. |

Groundwater use and management

Groundwater use

Most domestic water supplies in Burundi rely on groundwater, almost all from springs. It is reported that about 22,000 springs were used for water supply in 2010, compared to no more than 30 boreholes (Gutierrez and Barrat 2016). An earlier report (African Development Bank 2005) showed that at one point there were at least 35,000 developed natural springs in Burundi tapping groundwater for water supply, and 811 groundwater-based drinking water systems (likely to be drilled or dug wells equipped with hand pumps), but that most of these were non-functional. Lack of infrastructure development means there has been relatively little borehole drilling for water supply. In rural areas it is likely that people make use of groundwater from hand dug wells, possibly on a seasonal basis, as well as the numerous natural springs.

Groundwater management

Years of political instability have contributed to Burundi's water sector being in very poor state.

Several government bodies share responsibility for water resources and supplies. This can cause poor coordination of planning and water resource development, with competition in the allocation of water between sectors. The institutions involved include (USAID 2010):

- - The Directorate General for Water and Energy (DGEE) , within the Ministry of Water, Energy and Mines (MWEM), is responsible for overall water policy and administration

- - The Directorate of Water Resources (DRH), within DGEE, develops and maintains a national water master plan

- - The Directorate General of Rural Water and Electricity (DGHER) oversees rural drinking water and sanitation

- - The Water and Electric Authority (REGIDESO) is responsible for urban service provision

- - Communal Water Authorities are responsible for rural service provision and linked to District Users committees (African Development Fund 2005).

General improvement of water supplies in Burundi is a policy and development priority, and the urgency of this task means that there is a broad focus on all aspects of water resources and supply. Policies are focussed on implementing the principles of community based management and integrated water resource management (IWRM).

There is an attempt by government and some donors to encourage the development of the small amount of private sector involvement in the water sector. In 2005, the African Development Fund estimated there were 30 private consultancy firms in Burundi active in water services, such as borehole drilling.

A database was said in 2009 to have limited information about groundwater sources. A GIZ-supported project begun in 2012 included work to develop a central hydrogeological database at the national water authority.

Transboundary aquifers

For general information about transboundary aquifers, please see the Transboundary aquifers resources page

Groundwater Projects

Information on specific groundwater projects that have been carried out in Burundi, with web links to project results and outputs, can be found on the Burundi Groundwater Projects page.

References

Other references with more information on the geology and hydrogeology of Burundi may be available through the Africa Groundwater Literature Archive.

African Development Fund. 2005. Burundi: The rural water infrastructure rehabilitation and extension project. Appraisal report. Infrastructure Department Central and West Regions, Ocin, September 2005.

BRGM. 2016. Africa, a land of knowledge. Geosciences, no. 21. BRGM.

Gutierrez A and Barrat J-M. 2016. Groundwater resources of Burundi. New elements and decision making tools. 35th International Geological Congress : IGC 2016, Aug 2016, Cape Town, South Africa.

Hahne K. 2014. Lineament mapping for the localisation of high groundwater potential using remote sensing - Technical Report No. 4, prepared by IGEBU & BGR: 52 p, Hannover. (PDF, 9 MB)

Heckmann M, Vassolo S and Tiberghien C. 2016. Groundwater Vulnerability Map (COP) for the Nyanzari catchment, Gitega, Burundi. – Technical Report No. 7, prepared by IGEBU & BGR: 96 p, Hannover. (PDF, 6 MB)

Pfunt H, Tiberghien C and Vassolo S. 2016. Numerical Groundwater Model for the Nyanzare well field at the town of Gitega, Burundi. – Technical Report No. 8, prepared by IGEBU & BGR: 46 p, Hannover. (PDF, 2 MB)

PS Eau. 2013. Fiche Pays: Burundi

Schlüter T. 2006. Geological Atlas of Africa.

Tiberghien C, Nahimana N, Baranyiwa D, Valley S and Vassolo S. 2014. Présentation des captages d’eau potable de la ville de Gitega et évaluation de leurs qualités chimiques et bactériologiques en vue de la définition des périmètres de protection. Technical Report No 2 of the project “Management and Protection of Groundwater Resources in Burundi”, prepared by IGEBU & BGR: 42 p, Hanover.

Tiberghien C and Baranyikwa D. 2018. Estimation de volumes d‘eau prélevables de l’aquifère cristallin du champ captant de Gitega et de sa recharge. BGR Report No. 9, 29 p,

United Nations. 1989. Groundwater in Eastern, Central and Southern Africa: Burundi. United Nations Department of Technical Cooperation for Development.

Vassolo S and Krekeler T. 2013. Tracer Tests at Birohe Water Catchment, Gitega. Technical Report No 1 of the project “Management and Protection of Groundwater Resources in Burundi”, prepared by IGEBU & BGR: 12 p, Hanover.

USAID. 2010. Burundi Water and Sanitation Profile. March 2010.

Return to the index pages: Africa Groundwater Atlas >> Hydrogeology by country