Authors: Adrian Isles ([email protected]); Philipp Pfeiffenberger ([email protected]); David Turner ([email protected]); Todd Patterson ([email protected])

Please provide feedback to [email protected]

Embedding of third-party content in websites and mobile apps is a popular and effective technique for increasing user interest and engagement. The embedded content could be a social media post, audio, video, or other types of interactive media. In many cases, the content is owned by individual content creators and not the third-party platform which hosts the content. In order to protect the platform and provide creators with insight about how and where their content is consumed, third-party hosting platforms must be able to measure user engagement. For example, measuring the number of times users have listened, viewed, clicked or otherwise interacted with the embedded content on each top-level site. This allows for determining content and creator popularity, which provides creators with a mechanism for receiving credit on the third-party hosting platform ("content provider" hereafter).

A traditional approach for implementing this measurement involves third-party cookies or other forms of client-side state. With third-party cookies, content providers can store a persistent pseudonymous identifier (e.g. a visitor id) on the client, which acts as a session key. Content providers can then aggregate user events by visitor id to understand user behavior, including anomalous or potentially abusive engagement. For example, the ability to differentiate between 100 events from 100 distinct users versus 100 events from a single malicious user is paramount for abuse modeling and detection.

To improve user privacy in these contexts, major browser vendors including Safari, Mozilla and Chrome, have adopted or have plans to adopt client-side state partitioning by top-level site. Partitioning in this manner prevents client-side state from being shared across top-level sites, which prevents cross-site tracking. Despite these privacy improvements, there are still websites and apps that prefer stateless third-party embeddings in which the third party is restricted from accessing local storage or setting cookies, even if partitioned. The result is that engagement abuse detection becomes substantially more difficult. Third-party content providers have a legitimate need to protect creators, even within these stateless and cookieless environments. Specifically, content providers and content creators need to:

-

Accurately measure engagement. This includes counting engagement events on each top-level embedding site, but also detecting user sessions involved in abuse. For example, if a video is reportedly viewed a million times, it matters whether it is the result of engagement by a large organic audience versus the result of a small number of users manipulating engagement metrics by repeatedly clicking or viewing the content.

-

Perform access control. This means the ability of content providers to limit which top-level sites and mobile apps can embed their content. This is necessary to protect users from malicious developers who exploit third-party content in a way that is harmful or misleading. For example, app clones have historically been a popular approach for distribution of malware on Android and restricting access to content in such cases disrupts the incentive for users to install such apps.

We propose a new protocol "Randomized Counter-Abuse Tokens" (RCATs) for

detecting engagement abuse of third-party web content involving top-level sites

that require stateless third-party content embeddings. RCATs leverage existing

browser features and allow for third parties to detect fraudulent engagement

while remaining blind to a first-party user's identity. RCATs encode a

group-based identifier called RCAT Group ID. Approximately K users are

randomly assigned to each group, and the assignment is guaranteed to be stable

for a given user for some amount of time (i.e. ideally over a period of several

weeks). The Group ID is tied to a user's first-party identifier, but is

unlinkable by any third party who receives the Group ID. First party servers

control the randomization, generate the RCAT, and pass it as a parameter to the

third-party container (e.g. iframe or WebView).

Third-party content providers can use Group IDs to build statistical models for reasoning about abuse. For example, since the set of Group IDs are randomly assigned, the set of groups engaged with any piece of third-party content over a given time period should be uniformly distributed over Group IDs. A user, and therefore their Group ID, engaging with an individual piece of content an exceptionally high number of times would result in a non-uniform distribution. Similarly two users who are engaged in repeated coordinated activity involving third-party content can also be reasoned about statistically (i.e. two or more Group IDs coordinating to boost engagement of the same set of long tail content, can be discovered by computing the probability of such events occurring by chance). Content providers can then correct engagement metrics by selectively filtering engagements from groups behaving fraudulently.

- RCATs are not intended to be a replacement for partitioned cookies.

- A first party implementing RCATs needs to have access to a stable user identifier that it can use as a basis for doing the randomization. For example, a user's first party login ID, verified phone number or email address. First-party sites which do not have such IDs are ineligible to adopt RCATs.

The RCAT protocol depends on the existence of a first party and third party, which we define below:

- First party: In the case of web browsers, the first party owns the top frame's origin (i.e. the one appearing in the URL bar) of the document embedding third-party content. For content embedded inside of a WebView in a mobile application, the first party owns the mobile app.

- Third party: A web publisher or content provider which allows its content to be embedded in first-party documents or contexts. For simplicity of presentation, we assume that each piece of content has a unique content_id that corresponds to the URL from where the content can be embedded.

We assume that:

- First parties have a unique and stable identifier for each of their users.

This will be denoted as

first_party_uid. - Each party has generated a public/private cryptographic key pair, and public keys have been exchanged via some out-of-band mechanism. The first-party key pair is intended for signing, the third-party key pair is intended for encryption. The first-party signing key should not be reused to create RCATs for different third parties. See more details below regarding the recommended cryptographic schemes.

RCATs are intended to leverage the existing trust relationship that occurs between a user and first party. For example, a typical first-party social media or messaging application has access to sensitive user data that third parties traditionally do not have. This may include their first-party identity, social media consumption patterns and even contents of the private messages stored on their device. A user interacting with a first-party service via their mobile application or website must trust that it is processing and storing their data in a secure manner. This includes properly implementing data access controls, cryptographic protocols, encryption and secure random number generation. It should be noted that:

- RCATs require the correct protocol implementation by the first party.

- We assume a mutual distrust between the user and the third party.

- We require that the first party take reasonable steps to prevent access to its service by bots or malicious users known to engage in abuse. For example, a first party implementing RCATs must take reasonable steps to prevent bots from creating new first-party accounts to access embedded third-party content.

First-party servers must create a fresh and short-lived RCAT each time a user

loads embedded third-party content. Each RCAT contains a tuple (group_id,

content_binding, expiration) that is created on the first-party server. Both

group_id and content_binding are defined in the sections below, and the

expiration field specifies the Unix time after which the token should no longer

be considered valid. Before being exposed to user agents, the tuple must be

encrypted (so that only the intended third-party recipient can see the Group ID)

and signed (to allow authentication and prevent client-side forgery).

Formally, we represent an RCAT as ciphertext that is obtained by encrypting the string CONCAT(issuer_id, signature, payload) with the third

party's public encryption key, where:

issuer_idis a unique 32-bit value assigned by the third party to the first party and provided via some out-of-band mechanism. This id provides a more secure means of establishing first party identity as compared to relying on traditional user agent APIs, such as referer or ancestorOrigins (vulnerable to abuse in some contexts).signatureis the cryptographic signature over thepayload, generated by using the first party's private signing key.payloadis the tuple (group_id,content_binding,expiration).

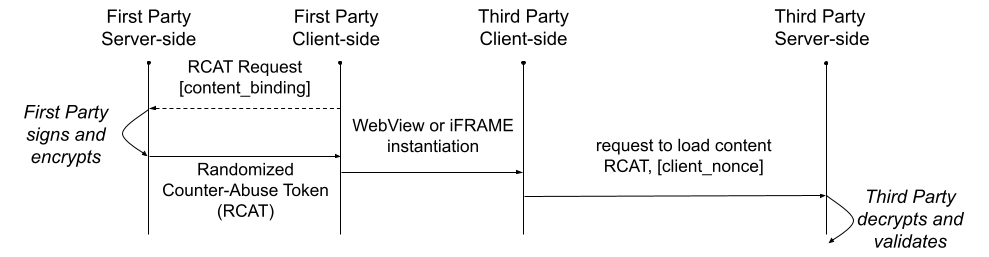

Once generated, RCATs can be passed to user agents and then forwarded to third

party servers on the initial request to load a resource. The overall flow is

given in the diagram below. Note that the optional client_nonce parameter is

needed to support verifying content binding in end-to-end encryption use cases.

Diagram 1: Data flow of RCAT issuance and validation.

A Group ID is a 64-bit value assigned by the first party to each user and is obtained by:

group_id =

Fsecret(first_party_uid) % Floor(N/K)

where:

Fsecretis the secure hashing function HMAC-SHA-256 keyed on a 256-bit randomly generated value (secret_first_party_salt) known only to the first party. In the case where a first party allows for embedding content from multiple different third-party content providers, a separate random value should be generated for each.Nis the number of unique first party identifiers expected to access the third party's content over the time period in which the Group ID is defined.Kis the group size parameter, whereN>K.

Note that the purpose of secret_first_party_salt is to prevent a malicious

third party from predicting a group_id given a first_party_uid obtained

out-of-band (e.g. a public list of email addresses, social media accounts, phone

numbers, etc). It also serves as a mechanism to prevent malicious users from

knowing their own Group IDs. This is an important abuse resistance mechanism, as

knowledge of which group a first party user has been assigned could allow

sophisticated attackers to coordinate in such a way that avoids detection by

downstream statistical models used to detect abuse. As a matter of cryptographic

hygiene, we recommend rotating secret_first_party_salt whenever N is

changed.

The content binding parameter (defined by content_binding) is a 64-bit

quantity that prevents the token from being reused outside the context for which

the token was intended. We assume each piece of content can be represented as a

string quantity. As mentioned above, the URL from which the content can be

embedded is likely the most common scenario, though both parties could mutually

agree to some other content identification scheme.

For use cases where the content_id is known to first-party servers, the

content binding can be obtained by:

content_binding =

Truncate(Fserver(content_id, 0), 8)

where Fserver is the secure hashing function

HMAC-SHA-256 keyed on the integer value 0, and the function output is truncated

to the first 8 bytes.

For end-to-end encrypted applications, first-party servers must be blind to the

content_id. In this case, the client must randomly generate a 256-bit nonce

(denoted by client_nonce) and then compute the binding as:

content_binding =

Truncate(Fclient(content_id, client_nonce), 8)

where Fclient is the secure hashing function

HMAC-SHA-256 keyed on the client_nonce, and the function output is truncated

to the first 8 bytes. The client must then forward content_binding to the

first party server so that it may generate the RCAT, and then send the

client_nonce along with the RCAT to the third party so that the third party

may verify the binding. The purpose of client_nonce is to inject entropy to

prevent a first party from using a dictionary attack on known content ids or

inferring when two users consume the same content. As such, the client_nonce

must never be revealed to the first-party's servers.

Given the content_id (and client_nonce for end-to-end encrypted

applications), a third-party server can validate RCATs using the following

procedure:

- Use the third-party's private key to decrypt the ciphertext and obtain the

(

issuer_id,signature,payload) tuple. - Verify the

signaturewith the first-party public key and deserialize thepayloadto (group_id,content_binding,expiration). - Use (

content_id,[client_nonce]) to recompute the content binding and verify that it matchescontent_bindingfrom thepayload. - Use the time of the current request to verify that the token has not expired.

The scope of this explainer is to define Randomized Counter-Abuse Tokens at the protocol level. That said, we believe it's important to consider the following areas for all implementations.

- RCATs require a secure, partitioned channel from which a token generated by the first party's server can be forwarded to the third party via a user agent. This could be accomplished through any number of mechanisms, such as an HTTP header, URL params, or Javascript APIs.

- Preferably, RCATs should be used only in cookieless environments where access to persistent storage is prevented by the user agent, since this makes the privacy trade-offs simpler. More specifically, RCATs and cookies (whether partitioned or unpartitioned) should not both be sent to third parties when loading content, since RCATs provides no incremental privacy protection to users beyond what partitioned cookies already provide.

We assume that a first party can accurately estimate the number of first-party

users accessing third-party content (N value). However in practice, N may be

difficult to predict as the number of unique first-party users accessing

third-party content may grow or shrink over time. In such cases, a first party

can recompute the Group IDs for all users by choosing a new

secret_first_party_salt and reassigning all users to new groups. More

incremental approaches for reassigning users to groups are possible, but we

leave that as future work. We also recommend that in the presence of

uncertainty, first parties should err on the side of being conservative when

estimating N. In particular, note that underestimating N will result in a

potentially larger expected number of users per Group ID, which has better

privacy properties for users than overestimating.

As a best practice, first-party servers should rotate secret_first_party_salt

regularly (e.g. at least once per month) and discard them once no longer in use.

Once the salt has been discarded neither the first party nor third party can

recover the Group ID mapping to first party user ids, even if they both collude.

This of course requires the first party to not retain logs containing the RCAT

nor any of the intermediate data used in its computation (e.g. content binding).

Strong cryptographic primitives are required for encryption and signing. RCATs support multiple primitives and algorithms, the complete list is available below:

Signing -

- ECDSA for curves P-256, P-384, P-521 with IEEE P1363 encoding.

- EdDSA with Curve25519 as defined in RFC 8032.

Encryption -

Asymmetric encryption should use "Hybrid Public Key Encryption" (HPKE) as defined in RFC 9180 with the following primitive values:

- KEM: X25519

- KDF: SHA 256

- AEAD: AES 256

For signing and encryption, choose from the list of supported primitives and algorithms described above. Note that the generated ciphertext must adhere to Tink's wire format.

- We assume that user agents have access to a secure pseudorandom number generator (PRNG).

- Any form of

client_noncereuse across multiple content identifiers may result in privacy loss. For example, a malicious third party could easily use nonces for tracking users across multiple playbacks and begin to infer more information than what the protocol aims to reveal. Resending the same (RCAT,client_nonce) pair for the samecontent_idmay also reveal more than intended, but we believe that doing so within a given short expiration period (e.g. retries, etc) is a reasonable privacy/performance trade-off.

In cases where the number of times a legitimate first-party user would typically consume a specific piece of third-party content is expected to be small, RCATs can be used to detect anomalous patterns without relying on a cookie or other types of user identifiers. These anomalies can be detected using a variety of abuse detection techniques and we provide representative examples below.

The threat model is malicious users engaged in consumption of excessive amounts of third-party content for the purpose of artificially inflating user engagement metrics. We consider two cases:

- A single "hot" user repeatedly consumes the same piece of content.

- A set of malicious users working in a coordinated fashion across multiple pieces of content.

Single User. For the single user case, detection relies on the assumption that no group should be more likely to consume a piece of content than another group. This can be formulated as a risk ratio (RR). That is, assume there is some user in group X consuming some third party content Y, then the following statistical test can be used:

RR = P(content_id=Y | group_id=X) /

P(content_id=Y | group_id!=X)

Statistically significant RRs greater than some threshold T > 1 can be assumed to be anomalous and, if so, requests involving (Y, X) can be filtered when computing engagement metrics on Y.

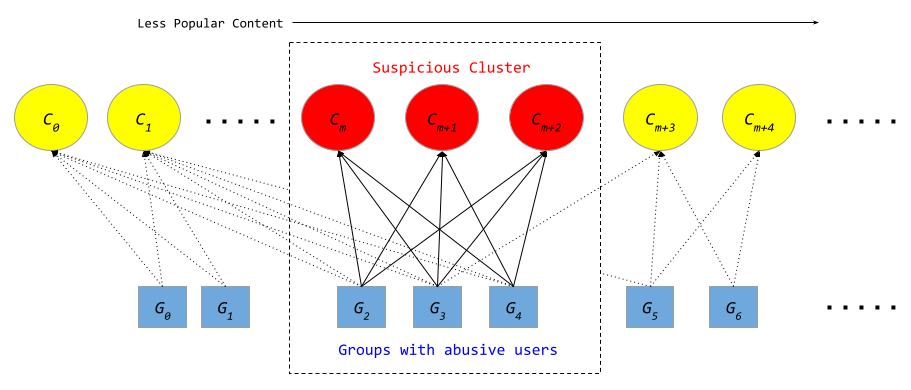

Multi-User Coordination. For the multiple user case, graph clustering can be used to detect anomalous coordination between users. A common approach is to build a bipartite graph between RCATs and all third party content, and then detect dense clusters (strongly connected components) that are considered suspicious. In the following diagram, the suspicious cluster consists of infrequently visited content that is consumed solely by three groups involving abusive users.

Diagram 2: Using RCATs to detect co-visits.

False Positives and K. For both of the applications above, the number of

potential false positives goes up as K increases.

- For example, in the single user case, when filtering anomalous (Y, X) pairs, all legitimate engagements by users in Group X who consume content Y will also be filtered.

- For graph clustering approaches, increasing

Kimplicitly increases the number of edges in the corresponding bipartite graph which could potentially create false strongly connected components that would otherwise not exist for smaller values ofK.

RCAT Group IDs prevent malicious third parties from inferring one or more of the

associated first_party_uids without access to additional side information. In

addition, the use of a secure cryptographic hash keyed on

secret_first_party_salt prevents:

- Cross site tracking. Specifically, third parties cannot use Group IDs sent by the same user to join embedded interactions made across different first-party sites. For example, even if two first parties rely on the same federated sign-in service, the resulting Group IDs would be distinct even if the federated service returns a common first-party identifier (e.g. a user's email address).

- Reverse dictionary attacks. Third parties cannot use first party identifiers obtained out-of-band to guess Group IDs corresponding to individual users. For example, a third party cannot take a list of publicly available first-party identifiers (e.g. usernames on first-party social media sites) and use them to infer the Group IDs of first-party users on the list.

The Group ID assignment procedure provides an expected privacy benefit of K.

That is, on average, a user can expect that there are K users that share the

same Group ID. However, we make no worse-case guarantees and the actual number

of users assigned to each Group ID may vary. By chance, some users may be

assigned to buckets with slightly more than K users, others slightly less.

Moreover, overestimating or under-estimating the parameter N may also impact

the actual number of users assigned to each bucket. In general a user should

expect that over a given time period with an accurate estimate for N, the

conditional entropy is H(F, G) >= log2(K), where F is a random variable

defined over the set of first_party_uids that accessed the third-party's

content and G the corresponding group_ids.

Ultimately, it's the first-party's responsibility to choose values for

parameters N, K that will yield statistical guarantees sufficient to address

their user's privacy concerns. We recommend a minimum K value of 100,

providing users with an expected group size of 100 users. Assuming that no

service will have more than 10 billion users (N = 10 billion), the chance of a

user being the sole member of a group is astronomically small (less than

10-35). For smaller N the probability will be smaller, and thus a

choice of K >= 100 should ensure that there are no single-user groups for any

service's user base. Nonetheless, it should be noted that even in the unlikely

worst-case scenario of a single-user group:

- The privacy properties would become similar to what can already be achieved in a third party setting using a partitioned visitor ID in the user's partitioned cookie jar.

- Without access to additional side information, it would still not be

possible for a malicious third party to obtain a

first_party_uidfrom a Group ID.

We encourage first parties implementing RCATs to perform a similar analysis

based on their choice of K and desired group size.

Groups can be combined with other information attached to a user's request (e.g. IP address, browser UserAgent, etc) to degrade the group size property and create a partitioned pseudo-identifier. However the worst case privacy risk reduces to what a third party could achieve through use of partitioned cookies which most modern browsers support in some form. Moreover, a user with a unique IP or rare UA can still be fingerprinted and globally tracked even without access to either RCATs or partitioned local storage. Such corner-cases are expected to be rare and various anti-fingerprinting efforts may serve to mitigate the privacy concern.

By allowing the content_binding to be generated on the client, the RCAT

protocol prevents first-party servers from accessing third-party content_ids.

However, first-party servers can learn metadata (e.g. the amount of third-party

content potentially consumed by a first-party user) as the protocol requires

clients to send requests to first-party servers for token generation. In some

cases, the leakage of the third-party domain appearing in a message may be

considered a privacy concern.

This concern can be addressed by issuing RCATs requests to the first party server for all encrypted messages, regardless of whether they contain third-party embedded content. Encrypted messages which do not require RCATs can use randomly generated content ids to create the content binding. In the case of multiple content providers, multiple RCAT tokens must be generated for each message - one for each content provider. This approach may of course have significant QPS impact, and so we briefly discuss two optimizations below (details are out-of-scope):

-

Use of Randomized Response. Depending on the privacy needs, a randomized response algorithm can be employed during RCAT generation to protect user privacy by injecting noise. Informally, the procedure involves use of two biased coins that return "heads" with probabilities p, q and can be described as follows:

- For each message, flip both coins on the client.

- If the first coin flip is heads, then request an RCAT token for the message only if it's required.

- Otherwise, if the second coin flip is also heads, then request an RCAT token even if it's not required for the message.

The parameters p and q provide tunable parameters that allow for a smooth trade-off between QPS overhead and privacy guarantees. Also, observe that the procedure allows for a

(1-p)*(1-q)probability that a message that requires an RCAT won't receive one. In such cases, content providers would need to - by policy - allow a certain amount of missing token requests for eachcontent_idor provide a degraded experience (e.g. link sharing - showing a simple hyperlink to the content, instead of embedding it). -

Send-side Content Binding. In this case, the message sender would generate the

client_nonceandcontent_binding, even in cases where one is not required. Theclient_noncewill be sent to the receiver over an end-to-end encrypted channel. Thecontent_binding, however, will be visible to first-party servers, allowing RCAT tokens to be generated while processing encrypted messages for delivery. RCATs corresponding to messages without content are superfluous and can be dropped by the recipient. This approach does not cause any additional QPS overhead, but it does cause an increase in bytes per message overhead.

RCATs are intended to be used for correcting third-party engagement metrics and

are not suitable for "banning" individual users by Group ID or otherwise

providing users with differentiated services based on specific Group ID

assignments. As noted in the sections above, RCATs provide built-in privacy

features (e.g. K sized cohorts, periodic group reassignments, cross-site

tracking prevention, etc) that mitigates the need for users to reset them to

address privacy concerns. That said, a first-party can optionally provide

controls for users to temporarily or permanently disable RCATs at the expense of

disabling embedded third-party content consumption. In this case, the user would

still be allowed to consume the content via traditional link sharing, which

would involve redirecting the user to the content provider's website using

either a browser or the content provider's mobile app.

RCAT is a platform agnostic protocol that allows a first-party to prevent an embedded third party from learning a user's first party identity while retaining the ability to detect engagement fraud. RCATs do not require a user agent API change and address a use case that remains unsolved by user agents. This section contrasts RCATs against existing and related user agent features.

Similar to RCAT, Trust tokens (TTs) require a trusted first party to issue tokens to a user which can be later redeemed in a third-party context. Trust tokens have strong privacy properties as neither a first party nor a third party can link a token issued to a user with their first-party identity. In practice, however, their strong privacy properties makes their counter-abuse properties extremely poor. Since TTs are unlinkable and not bound to any specific context, a malicious adversary can use TTs stolen from trusted users to falsely assert trust while engaging in abuse. Furthermore, tokens issued to first-party users that are later determined to be untrustworthy cannot be immediately revoked. The fact that they are untraceable to both parties makes them impractical for protecting against the threat models described in the "RCAT-Based Abuse Detection" section of this doc.

In comparison, note that RCATs:

- Provide users with unlinkability guarantees between ID spaces (a malicious third party cannot link a Group ID to a user's first-party identity). Note that the unlinkability guarantee is rooted in first-party trust, which must be made aware of the mapping.

- Support content binding, which binds RCATs to third-party content and limits the scope of any potential misuse.

- Does not require access to a user agent's partitioned storage. TT redemption implementations typically require the creation of a Signed Redemption Record (SRR) that must be cached on the user's device.

In order to reason about audience uniqueness, we require a uniformly random mapping of users to groups, which RCAT provides. FLoC, in contrast, assigned users to cohorts based on browsing history. Consequently, we would have seen legitimate concentrations of thematically related FLoC cohorts, which would have been indistinguishable from individual users' attempts to inflate metrics via replays. The topical affinity of a FLoC cohort would also have revealed some aspects of browsing history, which is not necessary for our use case; RCAT does not depend on any user history. Lastly, FLoC cohorts were globally specified, and thus would have introduced an avoidable risk of cross-site tracking to our application. In comparison, RCAT values are scoped to only a single top-level site and therefore do not pose a cross-site tracking concern.

RCATs are useful in cases where first parties would prefer not to provide third party access to per-user storage mechanisms, such as partitioned cookies. RCATs are designed and intended to address counter-abuse use cases. In comparison to partitioned cookies, their utility in non-abuse use cases is extremely limited.

We'd like to thank the following individuals for their help in reviewing and shaping this proposal: Josh Bao, Nick Doty (Center for Democracy and Technology), Kaustubha Govind, Joseph Lorenzo Hall (Internet Society), Paul Jensen, Michael Kleber, Brad Lassey, Fernando Lobato Meeser, Nathan Roach, Daniel Simmons-Marengo, Sergei Vassilvitskii, Mike West and Chris Wilson.