Sociological Images

Posts tagged gender

“I Felt Like Destroying Something Beautiful”

By Sandra Loughrin on May 17, 2018

When I was eight, my brother and I built a card house. He was obsessed with collecting baseball cards and had amassed thousands, taking up nearly every available corner of his childhood bedroom. After watching a particularly gripping episode of The Brady Bunch, in which Marsha and Greg settled a dispute by building a card house, we decided to stack the cards in our favor and build. Forty-eight hours later a seven-foot monstrosity emerged…and it was glorious.

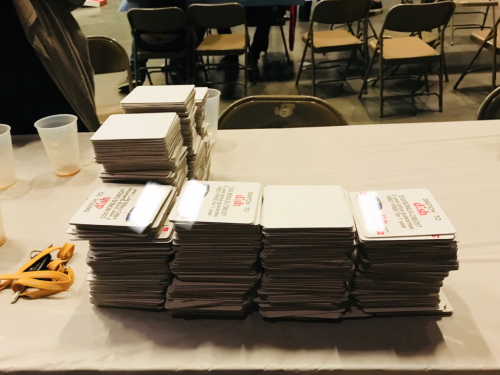

I told this story to a group of friends as I ran a stack of paper coasters through my fingers. We were attending Oktoberfest 2017 in a rural university town in the Midwest. They collectively decided I should flex my childhood skills and construct a coaster card house. Supplies were in abundance and time was no constraint.

I began to construct. Four levels in, people around us began to take notice; a few snapped pictures. Six levels in, people began to stop, actively take pictures, and inquire as to my progress and motivation. Eight stories in, a small crowd emerged. Everyone remained cordial and polite. At this point, it became clear that I was too short to continue building. In solidarity, one of my friends stood on a chair to encourage the build. We built the last three levels together, atop chairs, in the middle of the convention center.

Where inquires had been friendly in the early stages of building, the mood soon turned. The moment chairs were used to facilitate the building process was the moment nearly everyone in attendance began to take notice. As the final tier went up, objects began flying at my head. Although women remained cordial throughout, a fraction of the men in the crowd began to become more and more aggressive. Whispers of “I bet you $50 that you can’t knock it down” or “I’ll give you $20 if you go knock it down” were heard throughout. A man chatted with my husband, criticizing the structural integrity of the house and offering insight as to how his house would be better…if he were the one building. Finally, a group of very aggressive men began circling like vultures. One man chucked empty plastic cups from a few tables away. The card house was complete for a total of 2-minutes before it fell. The life of the tower ended as such:

Man: “Would you be mad if someone knocked it down?”

Me: “I’m the one who built it so I’m the one who gets to knock it down.”

Man: “What? You’re going to knock it down?”

The man proceeded to punch the right side of the structure; a quarter of the house fell. Before he could strike again, I stretched out my arms knocking down the remainder. A small curtsey followed, as if to say thank you for watching my performance. There was a mixture of cheers and boos. Cheers, I imagine from those who sat in nearby tables watching my progress throughout the night. Boos, I imagine, from those who were denied the pleasure of knocking down the structure themselves.

As an academic, it is difficult to remove my everyday experiences from research analysis. Likewise, as a gender scholar the aggression displayed by these men was particularly alarming. In an era of #metoo, we often speak of toxic masculinity as enacting masculine expectations through dominance, and even violence. We see men in power, typically white men, abuse this very power to justify sexual advances and sexual assault. We even see men justify mass shootings and attacks based on their perceived subordination and the denial of their patriarchal rights.

Yet toxic masculinity also exits on a smaller scale, in their everyday social worlds. Hegemonic masculinity is a more apt description for this destructive behavior, rather than outright violent behavior, as hegemonic masculinity describes a system of cultural meanings that gives men power — it is embedded in everything from religious doctrines, to wage structures, to mass media. As men learn hegemonic expectations by way of popular culture—from Humphrey Bogart to John Wayne—one cannot help but think of the famous line from the hyper-masculine Fight Club (1999), “I just wanted to destroy something beautiful.”

Power over women through hegemonic masculinity may best explain the actions of the men at Ocktoberfest. Alcohol consumption at the event allowed men greater freedom to justify their destructive behavior. Daring one another to physically remove a product of female labor, and their surprise at a woman’s choice to knock the tower down herself, are both in line with this type of power over women through the destruction of something “beautiful”.

Physical violence is not always a key feature of hegemonic masculinity (Connell 1987: 184). When we view toxic masculinity on a smaller scale, away from mass shootings and other high-profile tragedies, we find a form of masculinity that embraces aggression and destruction in our everyday social worlds, but is often excused as being innocent or unworthy of discussion.

Sandra Loughrin is an Assistant Professor at the University of Nebraska at Kearney. Her research areas include gender, sexuality, race, and age.

A Data Dive into Competitive A Cappella

By Evan Stewart on March 21, 2018

Source Photo: Ted Eytan, Flickr CC

It’s that time of year again! Fans across the nation are coming together to cheer on their colleges and universities in cutthroat competition. The drama is high and full of surprises as underdogs take on the established greats—some could even call it madness.

I’m talking, of course, about The International Championship of Collegiate A Cappella.

In case you missed the Pitch Perfect phenomenon, college a cappella has come a long way from the dulcet tones of Whiffenpoofs in the West Wing. Today, bands of eager singers are turning pop hits on their heads. Here’s a sampler, best enjoyed with headphones:

https://open.spotify.com/user/evanstewart/playlist/2aqG8exuGPqbmAzNDmhrIx

And competitive a cappella has gotten serious. Since its founding in 1996, the ICCA has turned into a massive national competition spawning a separate high school league and an open-entry, international competition for any signing group.

As a sociologist, watching niche hobbies turn into subcultures and subcultures turn into established institutions is fascinating. We even have data! Varsity Vocals publishes the results of each ICCA competition, including the scores and university affiliations of each group placing in the top-three of every quarterfinal, regional semifinal, and national final going back to 2006. I scraped the results from over 1300 placements to see what we can learn when a cappella meets analytics.

Watching a Conference Emerge

Organizational sociologists study how groups develop into functioning formal organizations by turning habits into routines and copying other established institutions. Over time, they watch how behaviors become more bureaucratic and standardized.

We can watch this happen with the ICCAs. Over the years, Varsity Vocals has established formal scoring guidelines, judging sheets, and practices for standardizing extreme scores. By graphing out the distribution of groups’ scores over the years, you can see the competition get more consistent in its scoring over time. The distributions narrow in range, and they take a more normal shape around about 350 points rather than skewing high or low.

Gender in the A Cappella World

Gender is a big deal in a cappella, because many groups define their membership by gender as a proxy for vocal range. Coed groups get a wider variety of voice parts, making their sound more versatile, but gender-exclusive groups can have an easier time getting a blended, uniform sound. This raises questions about gender and inequality, and there is a pretty big gender gap in who places at competition.

In light of this gap, one interesting trend is the explosion of coed a cappella groups over the past twelve years. These groups now make up a much larger proportion of placements, while all male and all female groups have been on the decline.

Who Are the Powerhouse Schools?

Just like March Madness, one of my favorite parts about the ICCA is the way it brings together all kinds of students and schools. You’d be surprised by some of the schools that lead on the national scene. Check out some of the top performances on YouTube, and stay tuned to see who takes the championship next month!

Evan Stewart is a Ph.D. candidate in sociology at the University of Minnesota. You can follow him on Twitter.

Gender, Bitcoin and Altcoins

By Joseph Gelfer PhD on March 16, 2018

Despite the fact that women played a key role in the development of modern technology, the digital domain is a disproportionately male space. Recent stories about the politics of GamerGate, “tech bros” in Silicon Valley, and resistance to diversity routinely surface despite efforts of companies such as Google to clean up their act by firing reactionary male employees.

The big tech story of the past year is unquestionably cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin. So it’s a good time to look at how cryptos replicate the gender politics of digital spaces and where they might complicate them.

Women’s Representation

Crypto holders are not evenly divided between men and women. One recent survey shows that 71% of Bitcoin holders are male. The first challenge for women is simply their representation within the crypto space.

There are various efforts on the part of individual women to address the imbalance. For example, Stacy Herbert, co-host of The Keiser Report, has recently been discussing the possibility of a women’s crypto conference noting, “I know so so many really smart women in the space but you go to these events and it’s panels of all the same guys again and again.” Technology commentator Alexia Tsotsis recently tweeted, “Women, consider crypto. Otherwise the men are going to get all the wealth, again.”

Clearly, the macho nature of the crypto community can feel exclusionary to women. Recently Bloomberg reported on a Bitcoin conference in Miami that invited attendees to an after-hours networking event held in a strip club. As one female attendee noted, “There was a message being sent to women, that, ‘OK, this isn’t really your place … this is where the boys roll.’”

The image of women as presented by altcoins (cryptocurrencies other than Bitcoin) is also telling. One can buy into TittieCoin or BigBoobsCoin, which need no further explanation. There is also an altcoin designed to resist this tendency, Women Coin: “Women coin will become the ultimate business coin for women. We all know that this altcoin market is mainly operated by men, just like the entire world. We want to stop this.”

Cryptomasculinities

The male dominance of cryptos suggests it is a space that celebrates normative masculinity. Certain celebrity endorsements of crypto projects have added to this mood, such as heavyweight boxer Floyd Mayweather, actor Steven Seagal and rapper Ghostface Killah. Crypto evangelist John McAfee routinely posts comments and pictures concerning guns, hookers and drugs. Reactionary responses to feminism can also be found: for example, patriarchal revivalist website Return of Kings published an article claiming, “Bitcoin proves that that ‘glass ceiling’ keeping women down is a myth.” Homophobia also occurs: when leading Bitcoin advocate Andreas Antonopoulos announced he was making a donation to the LGBTQ-focused Lambda Legal he received an array of homophobic comments.

However, it would be wrong to assume the masculinity promoted in the crypto space is monolithic. In particular, it is possible to identify a division between Bitcoin and altcoin holders. Consider the following image:

This image was tweeted with the caption “Bitcoin and Ethereum community can’t be anymore different.” On the left we have a MAGA hat-wearing, gun-toting Bitcoin holder; on the right the supposedly effeminate Vitalik Buterin, co-founder of the blockchain platform Ethereum. The longer you spend reading user-generated content in the crypto space, the more you get the sense that Bitcoin is “for men” while altcoins are framed as for snowflakes and SJWs.

There is an exception to this Bitcoin/altcoin gendered distinction: privacy coins such as Monero and Zcash appear to be deemed acceptably manly. Perhaps it is a coincidence that such altcoins are favored by Julian Assange, who has his own checkered history with gender politics ranging from his famed “masculinity test” through to the recent quips about feminists reported by The Intercept.

In conclusion, it is not surprising that the crypto space appears to be predominantly male and even outright resistant to fair representations of women. Certainly, it is not too dramatic to state that Bitcoin has a hyper-masculine culture, but Bitcoin does not represent the whole crypto space, and as both altcoins and other blockchain-based services become more diverse it is likely that so too will its representations of gender.

Joseph Gelfer is a researcher of men and masculinities. His books include Numen, Old Men: Contemporary Masculine Spiritualities and The Problem of Patriarchy and Masculinities in a Global Era. He is currently developing a new model for understanding masculinity, The Five Stages of Masculinity.

Digital Drag?

Allison Nobles on February 23, 2018

Screenshot used with permission

As I was scrolling through Facebook a few weeks ago, I noticed a new trend: Several friends posted pictures (via an app) of what they would look like as “the opposite sex.” Some of them were quite funny—my female-identified friends sported mustaches, while my male-identified friends revealed long flowing locks. But my sociologist-brain was curious: What makes this app so appealing? How does it decide what the “opposite sex” looks like? Assuming it grabs the users’ gender from their profiles, what would it do with users who listed their genders as non-binary, trans, or genderqueer? Would it assign them male or female? Would it crash? And, on a basic level, why are my friends partaking in this “game?”

Gender is deeply meaningful for our social world and for our identities—knowing someone’s gender gives us “cues” about how to categorize and connect with that person. Further, gender is an important way our social world is organized—for better or worse. Those who use the app engage with a part of their own identities and the world around them that is extremely significant and meaningful.

Gender is also performative. We “do” gender through the way we dress, talk, and take up space. In the same way, we read gender on people’s bodies and in how they interact with us. The app “changes people’s gender” by changing their gender performance; it alters their hair, face shape, eyes, and eyebrows. The app is thus a outlet to “play” with gender performance. In other words, it’s a way of doing digital drag. Drag is a term that is often used to refer to male-bodied people dressing in a feminine way (“drag queens”) or female-bodied people dressing in a masculine way (“drag kings”), but all people who do drag do not necessarily fit in this definition. Drag is ultimately about assuming and performing a gender. Drag is increasingly coming into the mainstream, as the popular reality TV series RuPaul’s Drag Race has been running for almost a decade now. As more people are exposed to the idea of playing with gender, we might see more of them trying it out in semi-public spaces like Facebook.

While playing with gender may be more common, it’s not all fun and games. The Facebook app in particular assumes a gender binary with clear distinctions between men and women, and this leaves many people out. While data on individuals outside of the gender binary is limited, a 2016 report from The Williams Institute estimated that 0.6% of the U.S. adult population — 1.4 million people — identify as transgender. Further, a Minnesota study of high schoolers found about 3% of the student population identify as transgender or gender nonconforming, and researchers in California estimate that 6% of adolescents are highly gender nonconforming and 20% are androgynous (equally masculine and feminine) in their gender performances.

The problem is that the stakes for challenging the gender binary are still quite high. Research shows people who do not fit neatly into the gender binary can face serious negative consequences, like discrimination and violence (including at least 28 killings of transgender individuals in 2017 and 4 already in 2018). And transgender individuals who are perceived as gender nonconforming by others tend to face more discrimination and negative health outcomes.

So, let’s all play with gender. Gender is messy and weird and mucking it up can be super fun. Let’s make a digital drag app that lets us play with gender in whatever way we please. But if we stick within the binary of male/female or man/woman, there are real consequences for those who live outside of the gender binary.

Recommended Readings:

- Baker Rogers. 2016. “Live Like a King Ya’ll: Gender Negotiation and the Performance of Masculinity among Southern Drag Kings.” Sexualities 19(½): 46-63.

- Judith Butler. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (1990) and Bodies that Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex (1993).

- Kristen Schilt and Laurel Westbrook. 2009. “Doing Gender, Doing Heteronormativity: ‘Gender Normals,’ Transgender People, and the Social Maintenance of Heterosexuality.” Gender & Society 23(4): 440–64.

Allison Nobles is a PhD candidate in sociology at the University of Minnesota and Graduate Editor at The Society Pages. Her research primarily focuses on sexuality and gender, and their intersections with race, immigration, and law.

Bros and Beer Snobs

By Evan Stewart on January 18, 2018

The rise of craft beer in the United States gives us more options than ever at happy hour. Choices in beer are closely tied to social class, and the market often veers into the world of pointlessly gendered products. Classic work in sociology has long studied how people use different cultural tastes to signal social status, but where once very particular tastes showed membership in the upper class—like a preference for fine wine and classical music—a world with more options offers status to people who consume a little bit of everything.

Photo Credit: Brian Gonzalez (Flickr CC)

But who gets to be an omnivore in the beer world? New research published in Social Currents by Helana Darwin shows how the new culture of craft beer still leans on old assumptions about gender and social status. In 2014, Darwin collected posts using gendered language from fifty beer blogs. She then visited four craft beer bars around New York City, surveying 93 patrons about the kinds of beer they would expect men and women to consume. Together, the results confirmed that customers tend to define “feminine” beer as light and fruity and “masculine” beer as strong, heavy, and darker.

Two interesting findings about what people do with these assumptions stand out. First, patrons admired women who drank masculine beer, but looked down on those who stuck to the feminine choices. Men, however, could have it both ways. Patrons described their choice to drink feminine beer as open-mindedness—the mark of a beer geek who could enjoy everything. Gender determined who got “credit” for having a broad range of taste.

Second, just like other exclusive markers of social status, the India Pale Ale held a hallowed place in craft brew culture to signify a select group of drinkers. Just like fancy wine, Darwin writes,

IPA constitutes an elite preference precisely because it is an acquired taste…inaccessible to those who lack the time, money, and desire to cultivate an appreciation for the taste.

Sociology can get a bad rap for being a buzzkill, and, if you’re going to partake, you should drink whatever you like. But this research provides an important look at how we build big assumptions about people into judgments about the smallest choices.

Evan Stewart is a Ph.D. candidate in sociology at the University of Minnesota. You can follow him on Twitter.

The Cost of Sexual Harassment

By Heather McLaughlin, Christopher Uggen, and Amy Blackstone on September 13, 2017

Originally posted at Gender & Society

Last summer, Donald Trump shared how he hoped his daughter Ivanka might respond should she be sexually harassed at work. He said, “I would like to think she would find another career or find another company if that was the case.” President Trump’s advice reflects what many American women feel forced to do when they’re harassed at work: quit their jobs. In our recent Gender & Society article, we examine how sexual harassment, and the job disruption that often accompanies it, affects women’s careers.

How many women quit and why? Our study shows how sexual harassment affects women at the early stages of their careers. Eighty percent of the women in our survey sample who reported either unwanted touching or a combination of other forms of harassment changed jobs within two years. Among women who were not harassed, only about half changed jobs over the same period. In our statistical models, women who were harassed were 6.5 times more likely than those who were not to change jobs. This was true after accounting for other factors – such as the birth of a child – that sometimes lead to job change. In addition to job change, industry change and reduced work hours were common after harassing experiences.

Percent of Working Women Who Change Jobs (2003–2005)

In interviews with some of these survey participants, we learned more about how sexual harassment affects employees. While some women quit work to avoid their harassers, others quit because of dissatisfaction with how employers responded to their reports of harassment.

Rachel, who worked at a fast food restaurant, told us that she was “just totally disgusted and I quit” after her employer failed to take action until they found out she had consulted an attorney. Many women who were harassed told us that leaving their positions felt like the only way to escape a toxic workplace climate. As advertising agency employee Hannah explained, “It wouldn’t be worth me trying to spend all my energy to change that culture.”

The Implications of Sexual Harassment for Women’s Careers Critics of Donald Trump’s remarks point out that many women who are harassed cannot afford to quit their jobs. Yet some feel they have no other option. Lisa, a project manager who was harassed at work, told us she decided, “That’s it, I’m outta here. I’ll eat rice and live in the dark if I have to.”

Our survey data show that women who were harassed at work report significantly greater financial stress two years later. The effect of sexual harassment was comparable to the strain caused by other negative life events, such as a serious injury or illness, incarceration, or assault. About 35 percent of this effect could be attributed to the job change that occurred after harassment.

For some of the women we interviewed, sexual harassment had other lasting effects that knocked them off-course during the formative early years of their career. Pam, for example, was less trusting after her harassment, and began a new job, for less pay, where she “wasn’t out in the public eye.” Other women were pushed toward less lucrative careers in fields where they believed sexual harassment and other sexist or discriminatory practices would be less likely to occur.

For those who stayed, challenging toxic workplace cultures also had costs. Even for women who were not harassed directly, standing up against harmful work environments resulted in ostracism, and career stagnation. By ignoring women’s concerns and pushing them out, organizational cultures that give rise to harassment remain unchallenged.

Rather than expecting women who are harassed to leave work, employers should consider the costs of maintaining workplace cultures that allow harassment to continue. Retaining good employees will reduce the high cost of turnover and allow all workers to thrive—which benefits employers and workers alike.

Heather McLaughlin is an assistant professor in Sociology at Oklahoma State University. Her research examines how gender norms are constructed and policed within various institutional contexts, including work, sport, and law, with a particular emphasis on adolescence and young adulthood. Christopher Uggen is Regents Professor and Martindale chair in Sociology and Law at the University of Minnesota. He studies crime, law, and social inequality, firm in the belief that good science can light the way to a more just and peaceful world. Amy Blackstone is a professor in Sociology and the Margaret Chase Smith Policy Center at the University of Maine. She studies childlessness and the childfree choice, workplace harassment, and civic engagement.

Flashback Friday: Race, gender, and benign nature in a vintage tobacco ad.

By Gwen Sharp, PhD

In Race, Ethnicity, and Sexuality, Joane Nagel looks at how these characteristics are used to create new national identities and frame colonial expansion. In particular, White female sexuality, presented as modest and appropriate, was often contrasted with the sexuality of colonized women, who were often depicted as promiscuous or immodest.

This 1860s advertisement for Peter Lorillard Snuff & Tobacco illustrates these differences. According to Toby and Will Musgrave, writing in An Empire of Plants, the ad drew on a purported Huron legend of a beautiful white spirit bringing them tobacco.

There are a few interesting things going on here. We have the association of femininity with a benign nature: the women are surrounded by various animals (monkeys, a fox and a rabbit, among others) who appear to pose no threat to the women or to one another. The background is lush and productive.

Racialized hierarchies are embedded in the personification of the “white spirit” as a White woman, descending from above to provide a precious gift to Native Americans, similar to imagery drawing on the idea of the “white man’s burden.”

And as often occurred (particularly as we entered the Victorian Era), there was a willingness to put non-White women’s bodies more obviously on display than the bodies of White women. The White woman above is actually less clothed than the American Indian woman, yet her arm and the white cloth are strategically placed to hide her breasts and crotch. On the other hand, the Native American woman’s breasts are fully displayed.

So, the ad provides a nice illustration of the personification of nations with women’s bodies, essentialized as close to nature, but arranged hierarchically according to race and perceived purity.

Originally posted in 2010.

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.

The average man thinks he’s smarter than the average women. And women generally agree.

By Lisa Wade, PhD

It starts early. At the age of five, most girls and boys think that their own sex is the smartest, a finding consistent with the idea that people tend to think more highly of people like themselves. Around age six, though, right when gender stereotypes tend to take hold among children, girls start reporting that they think boys are smarter, while boys continue to favor themselves and their male peers.

They may have learned this from their parents. Both mothers and fathers tend to think that their sons are smarter than their daughters. They’re more likely to ask Google if their son is a “genius” (though also whether they’re “stupid”). Regarding their daughters, they’re more likely to inquire about attractiveness.

Once in college, the trend continues. Male students overestimate the extent to which their males peers have “mastered” biology, for example, and underestimate their female peers’ mastery, even when grades and outspokenness were accounted for. To put a number on it, male students with a 3.00 G.P.A. were evaluated as equally smart as female students with a 3.75 G.P.A.

When young scholars go professional, the bias persists. More so than women, men go into and succeed in fields that are believed to require raw, innate brilliance, while women more so than men go into and succeed in fields that are believed to require only hard work.

Once in a field, if brilliance can be attributed to a man instead of a woman, it often will be. Within the field of economics, for example, solo-authored work increases a woman’s likelihood of getting tenure, a paper co-authored with a woman has an effect as well, but a paper co-authored with a man has zero effect. Male authors are given credit in all cases.

In negotiations over raises and promotions at work, women are more likely to be lied to, on the assumption that they’re not smart enough to figure out that they’re being given false information.

Overall, and across countries, men rate themselves as higher in analytical intelligence than women, and often women agree. Women are often rated as more verbally and emotionally intelligent, but the analytical types of intelligence (such as mathematical and spatial) are more strongly valued. When intelligence is not socially constructed as male, it’s constructed as masculine. Hypothetical figures presented as intelligent are judged as more masculine than less intelligent ones.

All this matters.

By age 6, some girls have already started opting out of playing games that they’re told are for “really, really smart” children. The same internalized sexism may lead young women to avoid academic disciplines that are believed to require raw intelligence. And, over the life course, women may be less likely than men to take advantage of career opportunities that they believe demand analytical thinking.

Lisa Wade, PhD is a professor at Occidental College. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture, and a textbook about gender. You can follow her on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

The study by a German feminist photographer that presaged the term “manspreading” by more than 30 years.

By Tristan Bridges, PhD

“Manspreading” is a relatively new term. According to Google Trends (above), the concept wasn’t really used before the end of 2014. But the idea it’s describing is not new at all. The notion that men occupy more space than women is one small piece of what Raewyn Connell refers to as the patriarchal dividend–the collection of accumulated advantages men collectively receive in androcentric patriarchal societies (e.g., wages, respect, authority, safety). Our bodies are differently disciplined to the systems of inequality in our societies depending upon our status within social hierarchies. And one seemingly small form of privilege from which many men benefit is the idea that men require (and are allowed) more space.

It’s not uncommon to see advertisements on all manner of public transportation today condemning the practice of occupying “too much” space while other around you “keep to themselves.” PSA’s like these are aimed at a very specific offender: some guy who’s sitting in a seat with his legs spread wide enough in a kind of V-shaped slump such that he is effectively occupying the seats around him as well.

I recently discovered what has got to be one of the most exhaustive treatments of the practice ever produced. It’s not the work of a sociologist; it’s the work of a German feminist photographer, Marianne Wex. In Wex’s treatment of the topic, Let’s Take Back Our Space: Female and Male Body Language as a Result of Patriarchal Structures (1984, translated from the German edition, published in 1979), she examines just shy of 5,000 photographs of men and women exhibiting body language that results from and plays a role in reproducing unequal gender relations.

The collection is organized by an laudable number of features of the various bodily positions. Interestingly, it was published in precisely the same year that Erving Goffman undertook a similar sociological study of what he referred to as “gender display” in his book, Gender Advertisements – though Goffman’s analysis utilized advertisements as the data under consideration.

Like Goffman, Wex examined the various details that made up bodily postures that seem to exude gender, addressing the ways our bodies are disciplined by society. Wex paired images according to the position of feet and legs, whether the body was situated to put weight on one or two legs, hand and arm positions, and much much more. And through this project, Wex also developed an astonishing vocabulary for body positions that she situates as the embodied manifestations of patriarchal social structures. The whole book organizes this incredible collection of (primarily) photographs she took between 1972 and 1977 by theme. On every page, men are depicted above women (as the above image illustrates) – a fact Wex saw as symbolizing the patriarchal structure of the society she sought to catalog so scrupulously. She even went so far as to examine bodily depiction throughout history as depicted in art to address the ways the patterns she discovered can be understood over time.

If you’re interested, you can watch the Youtube video of the entire book:

Tristan Bridges, PhD is a professor at The College at Brockport, SUNY. He is the co-editor of Exploring Masculinities: Identity, Inequality, Inequality, and Change with C.J. Pascoe and studies gender and sexual identity and inequality. You can follow him on Twitter here. Tristan also blogs regularly at Inequality by (Interior) Design.

The Superbowl and the problem with “femvertising” (featuring Audi, a company with zero board members).

By Nichole Fernández

The 2017 Super Bowl was an intense competition full of unexpected winners and high entertainment value. Alright, I didn’t actually watch the game, nor do I even know what teams were playing. I’m referring to the Super Bowl’s secondary contest, that of advertising. The Super Bowl is when many companies will roll out their most expensive and innovative advertisements. And this year there was a noticeable trend of socially aware advertising. Companies like Budweiser and 84 Lumber made statements on immigration. Airbnb and Coca-Cola celebrated American diversity. This socially conscious advertising is following the current political climate and riding the wave of increasing social movements. However, it also follows the industry’s movement towards social responsibility and activism.

One social activism Super Bowl commercial that created a significant buzz on social media this year was Audi, embedded above. The advertisement shows a young girl soapbox racing and a voiceover of her father wondering how to tell her about the difficulties she is bound to face just for being female. This commercial belongs to a form of socially responsible advertising often referred to as femvertising. Femvertising is a term used to describe mainstream commercial advertising that attempts to promote female empowerment or challenge gender stereotypes.

Despite the Internet’s response to this advertisement with a sexist pushback against feminism, this commercial is not exactly feminist. While at its core this advertisement is sending a fundamentally feminist argument of gender equality and fair wages, it feels disempowering to have a man explain sexism. It feels a little like “mansplaining” with moments reminiscent of the male “savior” trope. There is also a very timid relationship between the fight for gender equality and the product being sold. The advertisement is attempting to associate Audi with feminist ideals, but the reality is that with no female board members Audi is not exactly practicing what they preach. There are many reasons why ‘femverstising’ in general is problematic (not including contested relationship between feminism and capitalism). Here I will point out three problems with this new trend of socially ‘responsible’ femvertising.

1. The industry

The advertising industry is not known for its diversity nor is it known for its accurate representation women. So right away the industry doesn’t instill confidence in those hoping for more socially aware and diverse advertising. The way advertising works is to promote a brand identity by drawing on social symbols that make products like Channel perfume a signifier of French sophistication and Marlboro cigarettes an icon of American rugged masculinity. Therefore companies are selling an identity just as much as the product itself, while corporations that employ feminist advertising are instead appropriating feminist ideologies.

They are appropriating not social signifiers of an idealized lifestyle, but rather the whole historical baggage and gendered experiences women. This appropriation at its core is not for social progress and empowerment, but to sell a product. The whole industry functions by using these identities for material gain. As feminism becomes more popular with young women, it then becomes a profitable and desirable identity to implement. The whole concept is against feminist ideology because feminism is not for sale. Using feminist arguments to sell products may be better than perpetuating gender stereotypes but it is still using these ideologies like trying on a new style of dress that can be taken off at night rather than embodying the messages of feminism that they are borrowing. This brings us to the next point.

2. Sometimes it’s the Wrong Solution

Lets consider Dove, the toiletries company that has gained a fair amount of notoriety for their social advertising and small-scale outreach programs for women and girls. Their advertisements are famous for endorsing the body positive movement. But in general the connection between female empowerment and what they actually sell is weak. Which makes it feel insincere and a lot like pandering. Why doesn’t Dove just make products that are more aligned with feminist ideologies in the first place? If feminist consumers are what they want, then make feminist products. Don’t try to just apply feminist concepts as an afterthought in hopes of increasing consumer sales.

Dove is a beauty company that is benefiting from products that are aimed at promoting a very gendered ideal of beauty. The company itself is part of the problem so its femvertising makes me feel like Dove (and their parent company Unileaver) is trying to deny that they are playing a huge role in the creation of these stereotypes that they are claiming to be challenging. If you want to really empower women then don’t just do it in your branding start with the products you are making, examine your business model, and challenge the industry as whole. Feminist concepts should run through the entire core of your business before you try to sell it to your consumers. We don’t need feminist advertising, we need a system that is not actively continuing to increase a gender divide where women are meant to be beautiful and expected to purchase the beauty products that Dove sells. Using feminist inspired advertising doesn’t solve this underlying core problem it just masks it. Femvertising therefore is often the wrong solution, or really not even a solution at all.

3. Femvertising shouldn’t have to be a term

We really shouldn’t be in a situation where all advertising is so un-feminist and so degrading towards women that there is a term for advertising that simply depicts women as powerful. When the bar is set so low we shouldn’t praise companies for doing the minimum required to represent women both accurately and positively. We should be holding our advertising, media, and all other forms of visual representation to much higher standards. Femvertising shouldn’t be a thing because we shouldn’t have to give a term to what responsible advertising agencies should be aiming for when they represent women.

So as to not leave you on a depressing and negative note, here are three advertisements that should be acknowledged for actively challenge the norms:

Nichole Fernández is a PhD candidate in sociology at the University of Edinburgh. Her research explores the representation of the nation in tourism advertisement. Follow Nichole on twitter here.

Page 1 of 7