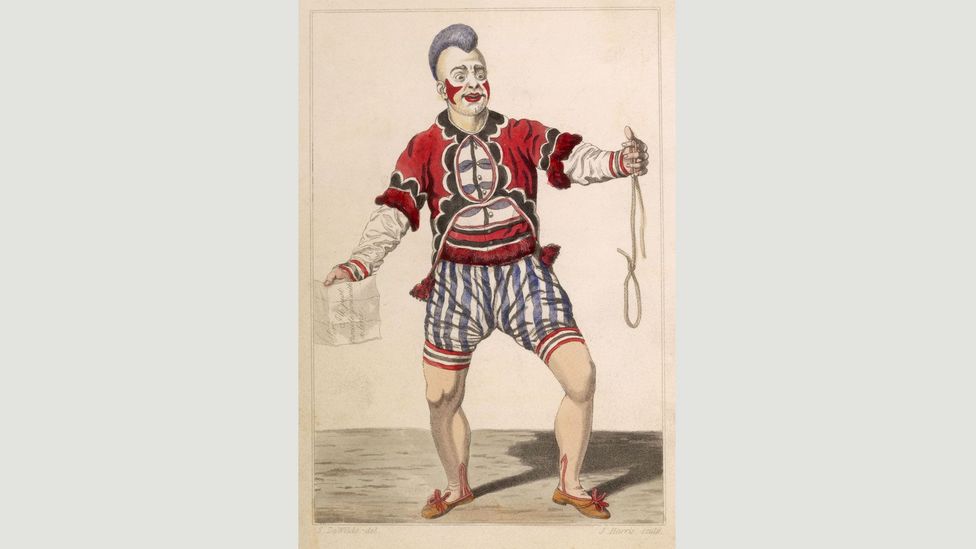

“Day after day he sat before the mirror, brush in hand, marking his features, wiping them clean, and starting again, until finally a face emerged from the candlelight that bore a grin so incendiary it refused to be erased,” writes Andrew McConnell Stott in his acclaimed biography The Pantomime Life of Joseph Grimaldi.

“It began with a thick foundation of greasepaint, applied to every exposed inch of face, neck and chest… He fixed it with a cloud of powder, then painted a blood-red wound, a mile-wide smear of jam, to form the gaping, gluttonous cavern of a mouth. The eyes, wide and rolling, were arched by thick brows… each cheek received a red chevron that conveyed insolently rude health while being simultaneously suggestive of some exotic beast of Hindu demonology.”

As a description of a mask, it is disturbing. As a description of the modern clown, it is insightful: when these purveyors of mayhem moved from the stage to the circus ring, they continued to be as unsettling as they were amusing.

Joseph Grimaldi is seen as the forerunner to the modern clown – an annual ‘clown’s service’ is held at a church in London in his honour (Credit: Alamy)

It was at the turn of the 19th Century when the British pantomime star Grimaldi honed his alter-ego Joey, a character that was the forerunner to the clown we know today – currently terrorising people around the world in a spiralling ‘clown-demic’. Reports of clowns attempting to lure children into woods in the US state of South Carolina first emerged in August. Since then, there have been sightings of clowns behaving in menacing ways around the world: the social panic has led to a backlash, with arrests, school lockdowns and local officials banning clown costumes at Halloween. McDonald’s has limited Ronald McDonald’s public appearances and a ‘Clown Lives Matter’ march scheduled in Arizona had to be cancelled after organisers received death threats.

The craze has been condemned by professional clowns, who claim it might threaten their livelihood and “risks permanently damaging the reputation of the artform”. Yet clowns have not always been unthreatening children’s entertainers: when Grimaldi transformed himself into Joey, he was tapping into a tradition that stretched back thousands of years.

Gallows humour

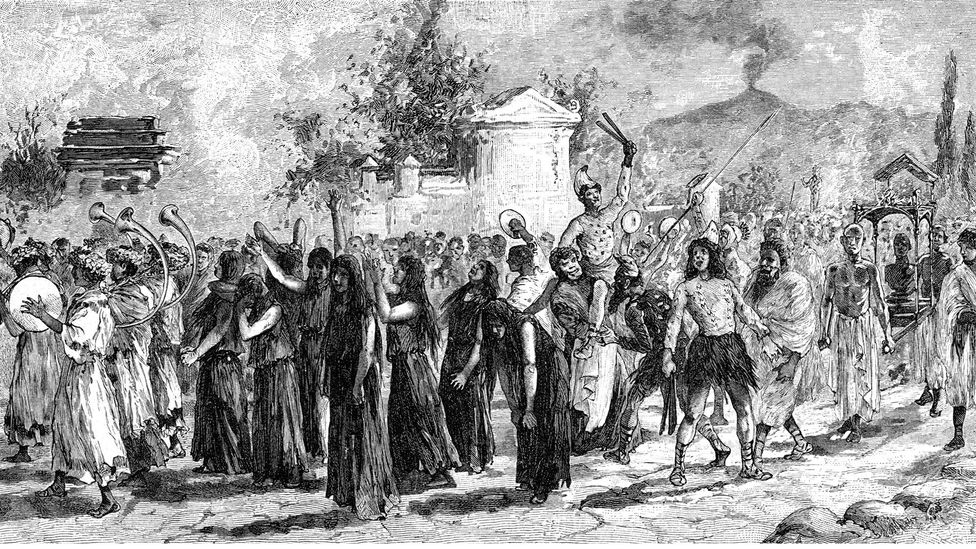

There are accounts of a funny man in ancient Rome who performed impressions of the deceased – at their own funerals. The archimimus was allowed to offend even mourning family members. Lucius M Sargent recounts how Suetonius, in his Life of Tiberius, described one at the funeral for the emperor Vespasian. “It was his business to imitate the voice, manner and gestures of the defunct,” writes Sargent. “The fellow openly cracks his jokes on the absurd expense of the funeral.”

Jester figures attended ancient Roman funerals, as this image of a procession in Pompeii circa 50 AD shows (Credit: Alamy)

The archimimus of Rome took liberties in the same way as the court jesters of medieval European royalty. “The court jester was given licence to say things that might be rude or impolitic or socially unacceptable – even about the king,” says Benjamin Radford, author of Bad Clowns. “He could make fun of a king’s weight or how young his concubines were, and not be put to death for it because of the clown’s role as a truthsayer.

It’s a mistake to ask when did clowns go bad – because they were never ‘good’ to begin with – Benjamin Radford

“If you take a broader look at the history of the clown, they have always been an ambiguous figure. Sometimes they’re laughing at themselves, sometimes they’re laughing at you – sometimes they’re the victim, sometimes you’re the victim. It’s a mistake to ask when did clowns go bad – because they were never ‘good’ to begin with,” he says. “You see this in the harlequin character, and of course in Mr Punch – that is a classic evil clown archetype which has been performed in England for more than 300 years. It’s this beloved character who is both funny and evil. That’s an irresistible stew to many people.”

Created in the Italian commedia dell’arte, the Harlequin character took on a different role as pantomime developed in England in the 18th Century (Credit: Shutterstock)

Radford sees echoes today. “Donald Trump has exploited aspects of the evil clown perfectly – he’s a showman, a performer, he insults people and then when called on it, he says ‘I was just joking’ – he does it for attention, as clowns do. Regardless of how you feel about Trump, there are many clear parallels to the evil clown character.”

Masking fears

In his research, Radford was surprised by the range of places in which the archetype appears. “Once you begin picking up the threads and identify common themes in the evil clown character, they pop out,” he says.

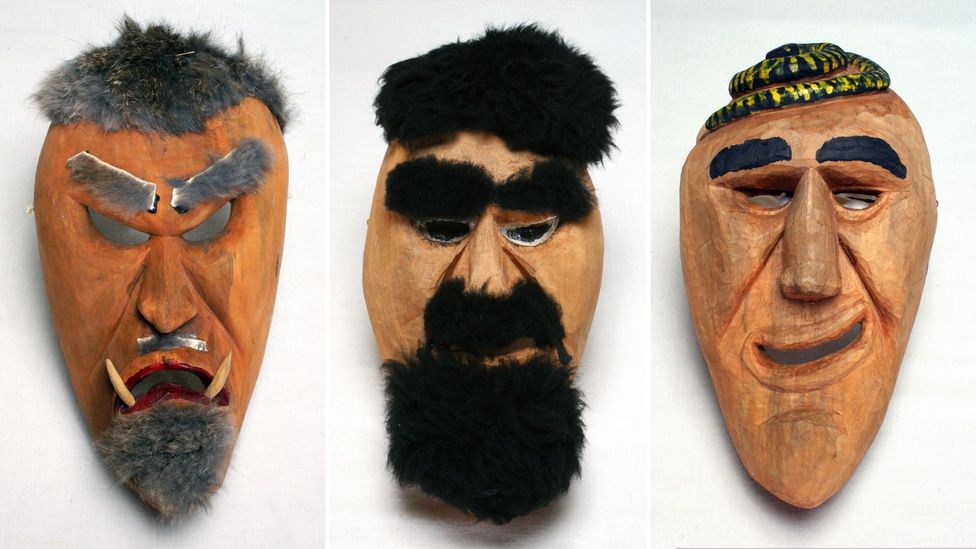

For centuries, the Cherokee people of North America have performed a ritual reacting against outsider intrusion. The Booger Dance begins with a prelude in which tribe members dance together for around 30 minutes; then a group of up to 10 males arrive, wearing masks representing foreigners – often disfigured as though infected with smallpox. American anthropologist Dr Frank Gouldsmith Speck observed performances in 1935 and 1936 at a Cherokee reservation in western North Carolina. In his book Cherokee Dance and Drama, he describes how the masked company “boisterously enters the house where the night dance party is held. The maskers are systematically malignant. On entering, some of them act mad, fall on the floor, hit at the spectators… and chase the girls.”

Booger masks of the Cherokee people of North Carolina are worn to represent outsiders during the performance of a ritual dance (Credit: Mathers Museum of World Cultures/Flickr)

This is the tightrope walked by the clown: anarchy contained just enough to allow for laughter

There is humour as well as menace in the ritual. For the main part, each masked man “performs awkward and grotesque steps, as if he were a clumsy white man trying to imitate Indian dancing”. This continues “until all the masked visitors have competed in drawing applause by their obscene names and clowning”. At the arrival of the Boogers, Speck notes, “when the first invader was questioned about his nationality and identity, he resoundingly broke wind and this was greeted by risible applause”.

This is the tightrope walked by the clown: anarchy contained just enough to allow for laughter, a threat that dissolves into an object of ridicule. When that balance tips the wrong way, it’s a quick slide into horror. Philosophy professor David Livingstone Smith believes the mismatch between appearance and action is what makes clowns creepy.

Psychologists have found that people find clowns creepy because they can’t see their real expressions (Credit: Alamy)

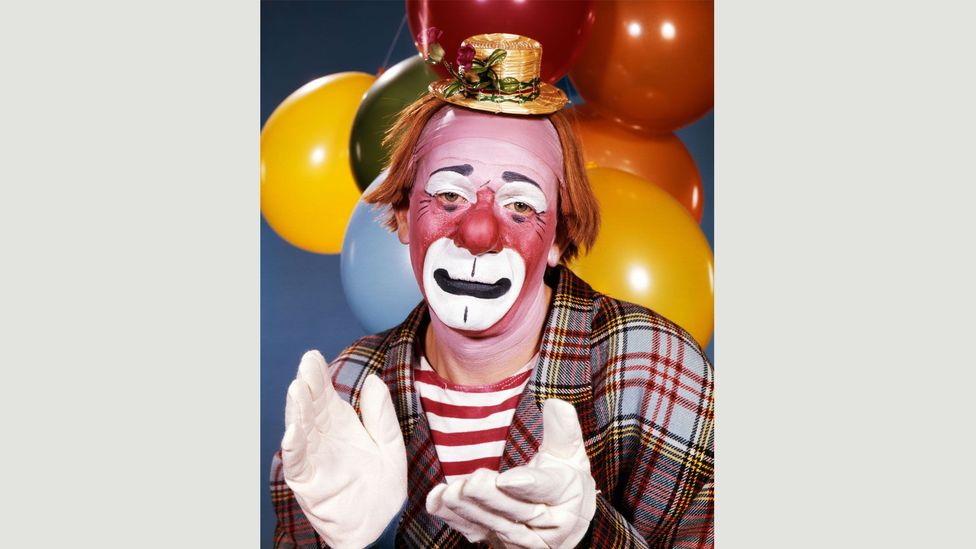

“Clowns are peculiar because they’re meant to be delightful and amusing but a lot of people find them disturbing,” he tells BBC Culture, referencing the 2016 research paper On the Nature of Creepiness. Psychologists Francis McAndrew and Sara Koehnke of Knox College in Illinois asked more than 1,000 people to rate the creepiness of a list of occupations as part of a wider survey. “Clowns won the creepiness jackpot,” says Livingstone Smith.

The study concluded that “being ‘creeped out’ is an evolved adaptive emotional response to ambiguity about the presence of threat”: in other words, as Smith wrote on the website Aeon, “a person is creepy if we are uncertain about whether he or she is someone to fear”.

The fears of a clown

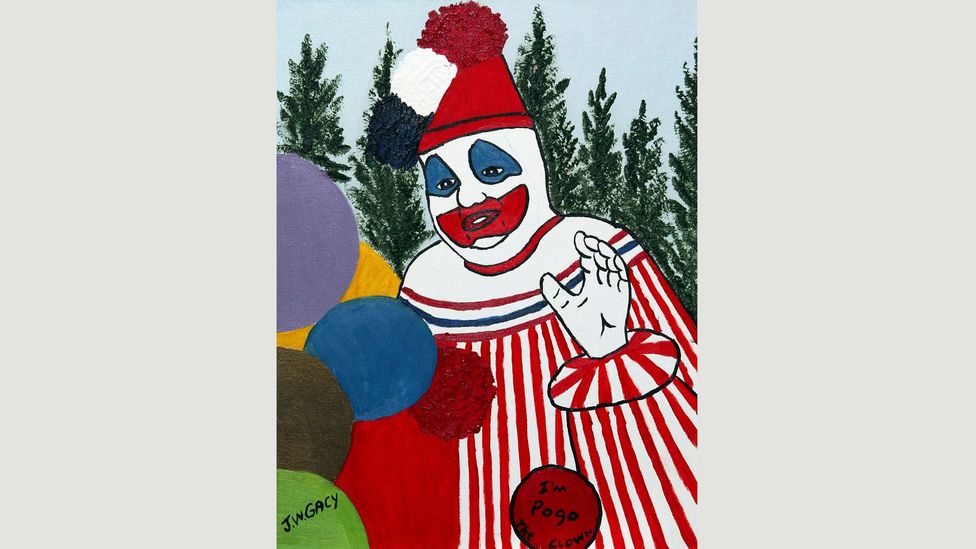

This inherent creepiness was taken to an extreme with the idea of the ‘killer clown’: the character that pranksters are currently bringing into streets and alleyways across the globe. Some argue that this began with the arrest of serial killer John Wayne Gacy in 1978. Gacy had dressed as ‘Pogo the Clown’ at children’s parties, and made a series of clown paintings while on death row. He is often touted as the inspiration for Pennywise in Stephen King’s 1986 horror novel It (King has recently spoken out about the ‘killer clown’ trend, saying: “time to cool the clown hysteria – most of ‘em are good, cheer up the kiddies, make people laugh”.)

Stephen King’s 1986 horror novel It featured a killer clown, Pennywise, played by Tim Curry (pictured) in a TV adaptation (Credit: Alamy)

Yet it’s a strand of popular culture that extends back far beyond Pennywise. Ruggero Leoncavallo’s 1892 opera Pagliacci (which means ‘clowns’ in Italian) features a clown who discovers his wife is cheating on him, and murders her on stage. In one of the opera’s arias, the clown laments that his job is to make the audience laugh, even if he is crying inside – he later sings “Se il viso è pallido, è di vergogna”: “if my face is white, it is for shame”. French playwright Catulle Mendes claimed Leoncavallo stole the plot from his 1887 play La Femme de Tabarin, in which a clown also murders his cheating wife on stage: as she is dying, she smears her husband’s lips with her blood.

The potential for clowns to invoke fear was widely recognised at that time. In 1879, the French writer Edmond de Goncourt wrote that clowns’ “frolicking and jumping doesn’t try to amuse the eye, but rather manages to give birth to troubled astonishment and emotions of fear and almost painful surprises from this strange and unhealthy motion of body and muscle [with] visions of Bedlam, of the amphitheatre of anatomy, of the morgue.” He calls clowns “modern phantoms of the night”, whose actions are “idiotic gesticulations, the agitated mimicry of a band of madmen”.

Serial killer John Wayne Gacy dressed as ‘Pogo the clown’ at children’s parties: this is one of the paintings he made while on death row (Credit: Alamy)

Madness was arguably part of the appeal of Grimaldi. Trained in clowning by an abusive, tyrannical father, he retreated into childhood with the character Joey. According to Stott however, this “was categorically not a return to innocence – there was little comfort to be had in revisiting a period of his life that had been unrelentingly complex and traumatic”. Grimaldi had been left crippled by injuries from decades of slapstick tumbling, and was in constant pain. “I am ‘Grim all day’,” he joked, “but I make you laugh at night.” Prone to depression, with an alcoholic son who died at the age of 30, Grimaldi took to the bottle himself and died in poverty.

Make ‘em laugh

At the age of 25, Charles Dickens was asked to edit Grimaldi’s memoirs, shortly after the great clown’s death in 1837. Dickens had already written The Pickwick Papers, which featured a character said to be based on Grimaldi’s son: “the glassy eyes, contrasting fearfully with the thick white paint with which the face was besmeared; the grotesquely-ornamented head, trembling with paralysis, and the long skinny hands, rubbed with white chalk – all gave him a hideous and unnatural appearance”.

Stott has written that, through these memoirs, “laughter and misery becomes the balance-beam on which Grimaldi’s existence is constantly weighed as every career triumph is paid for with a proportionate personal agony, and every moment of joy countered by grief.”

It’s the belief that clowns are meant to be harmless that is recent, not the idea that they are unsettling. “There’s an ambiguity about what kind of thing they are,” says Livingstone Smith. “If clowns reconfigured themselves such that the ambiguity was diminished, they wouldn’t be as disturbing.” But arguably, they’d also no longer be clowns.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, Travel and Autos, delivered to your inbox every Friday.