Foreign visitors to Athens are often stunned by the appearance of the city. A sprawling metropolis of ugly concrete apartment blocks, it has neither the classical grace usually associated with ancient Athens, nor the Baroque splendour of comparable cities like Rome. So, how did Athens come to look like this?

More like this:

- Ten dream homes from the past century

- The most tranquil library in the world?

- The design geniuses who fled turmoil

To begin with, Athens was never meant to be the capital of Greece at all, having ceased to be a settlement of any importance for several centuries. By the time of the Greek War of Independence in 1821, it had been reduced to a ramshackle village of around 4,000 inhabitants. Consequently, the Greek revolutionaries had selected the busy port town of Nafplio to be the capital of their new state.

The Old University of Athens is one of the city’s best-known Neoclassical buildings (Credit: Alamy)

But the Western powers, such as France and Britain, who had provided financial and military support to Greece during the war, insisted on Athens as the capital. Motivated by a romanticised idealism of ancient Greece, they sent a team of architects to Athens with the goal of reviving the classical Greek architectural model. The most notable of these were Danish architect Theophil Hansen, Saxon Ernst Ziller and Greek Stamatis Kleanthis.

In the ensuing decades, Athens was largely stripped of its Ottoman, Frankish and even Byzantine trappings. The meandering streets were replaced by orthogonal grids, while existing buildings were torn down and replaced by grand, Neoclassical edifices intended to express the continuity of ancient Athens in architectural form.

It was a beautiful city of wide avenues, grand squares and fine, Neoclassical architecture – so what happened?

The vivid fantasy that the west had imposed on Athens bore little relation to the Greece of the 19th Century. However, the Greeks gradually came to adopt it as their own. Long after the foreign architects had returned home, they continued to build themselves Neoclassical houses, often adding unique structural and stylistic elements. The result was a uniquely ‘Greek’ style of Neoclassicism that was noticeably different from elsewhere in Europe.

Athens, photographed between 1850 and 1880 (Credit: Library of Congress/ Image from Builders, Housewives and the Construction of Modern Athens by Ioanna Theocharopoulou)

Photographs from the early 20th Century depict a beautiful city of wide avenues, grand squares and fine, Neoclassical architecture fanning out between the hills of the Acropolis and Lycabettus. The population swelled to 120,000, and Athens was beginning to look like a European capital city. So what happened?

In the first half of the 20th Century, Greece was hit by three successive catastrophes. The first was the Greek-Turkish population exchange (1922-23) that saw 1.5 million Greek refugees leave Turkey and settle in Greece. Roughly a quarter were settled in Athens, raising the population of the city from 200,000 to more than 500,000 in a few months. Then, the Axis Occupation of Greece (1941-45) saw the almost total destruction of Greece’s industry, agriculture and infrastructure, while the ensuing Greek Civil War (1946-49) left the country bitterly divided along political, social and economic lines. By the time the civil war was over, Greece was in very bad shape.

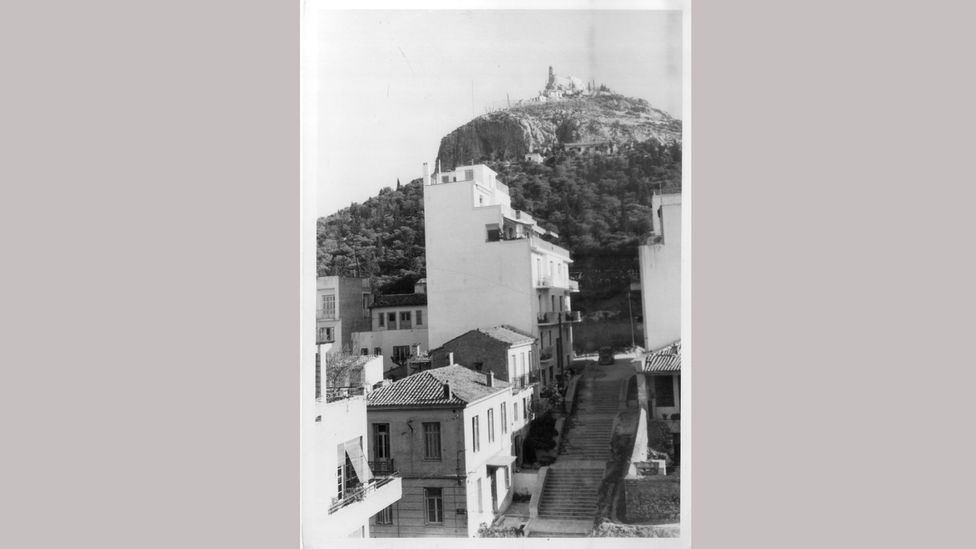

Athens, 1950s, (Credit: Benaki Museum, Costas Megalokonomou Archives/ Image from Builders, Housewives and the Construction of Modern Athens by Ioanna Theocharopoulou)

In Athens, the refugees from 1923 were still living in temporary shelters, while the city’s middle class, who traditionally inhabited the Neoclassical mansions, barely had enough money to feed themselves, let alone repair their damaged homes. Meanwhile, Greeks poured into Athens, looking to escape the devastation and poverty in the countryside. During the 1950s, an estimated 560,000 internal migrants came to Athens, doubling the population once more.

The state, which had spent most of its Marshall Aid funds on simply trying to survive the civil war, had neither the tools nor the money to build any housing. Hunger was widespread. Violence, motivated both by politics and by economic inequality, was rife. The situation was desperate. A radical solution had to be found.

Radical solution

That radical solution came not from above, but from below; from a unique system known as antiparochi. Antiparochi – which has no exact translation in English but can roughly be defined as ‘mutual exchange’ – would become the defining feature of Athens’ urban landscape. To put it simply, antiparochi is why Athens looks like Athens.

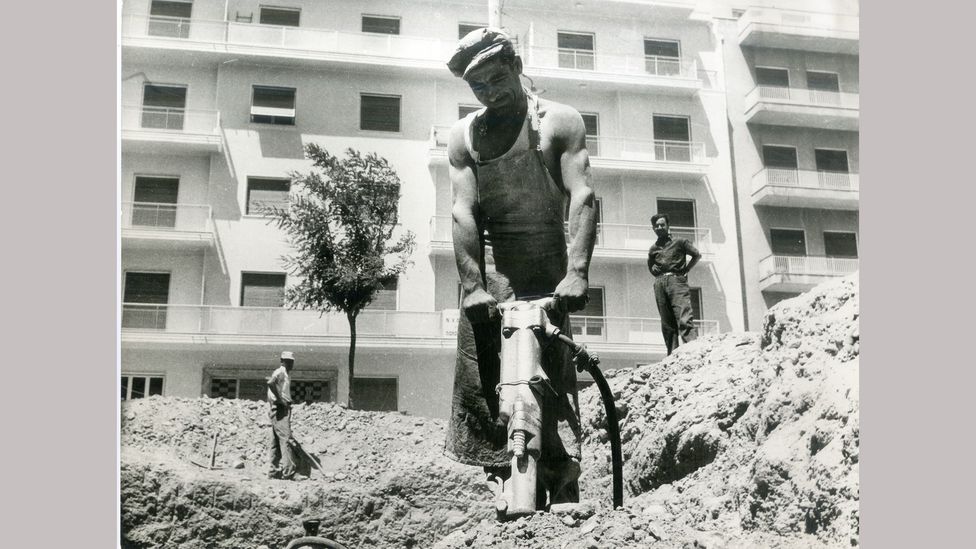

Construction in the 1950s (Credit: Benaki Museum, Costas Megalokonomou Archives/ Image from Builders, Housewives and the Construction of Modern Athens by Ioanna Theocharopoulou)

Here’s how it worked: a contractor would approach the owner of a house and offer him a deal. He would knock down his house, and build a block of flats in its place. In return, the homeowner would be given a certain number of flats (usually two or three), while the contractor would then make his money by selling the remaining flats to Greeks who were seeking accommodation. Generally, no money was exchanged and no contracts were signed.

What’s so incredible about antiparochi is that it emerged spontaneously out of the housing crisis in Athens. “There was no specific law which told people ‘OK now you have the right to collaborate and build whatever you like’. It was the people themselves that found out this possibility,” says Panos Dragonas, professor of Architecture at the University of Patras.

Even more incredibly, the state completely accepted what its citizens had started doing, introducing only a few minor regulations, such as a maximum height for the apartment buildings – known as polykatoikies in Greek – and a ban on building over archaeological sites or on top of Athens’ seven historical hills. There were no property taxes – the state never made any direct income from antiparochi.

The elegance of antiparochi was that it appeared to solve all of Greece’s problems at once. It provided homeowners and home seekers with modern apartments, while creating enough profit for the contractors to continue investing in construction without state subsidies or bank loans.

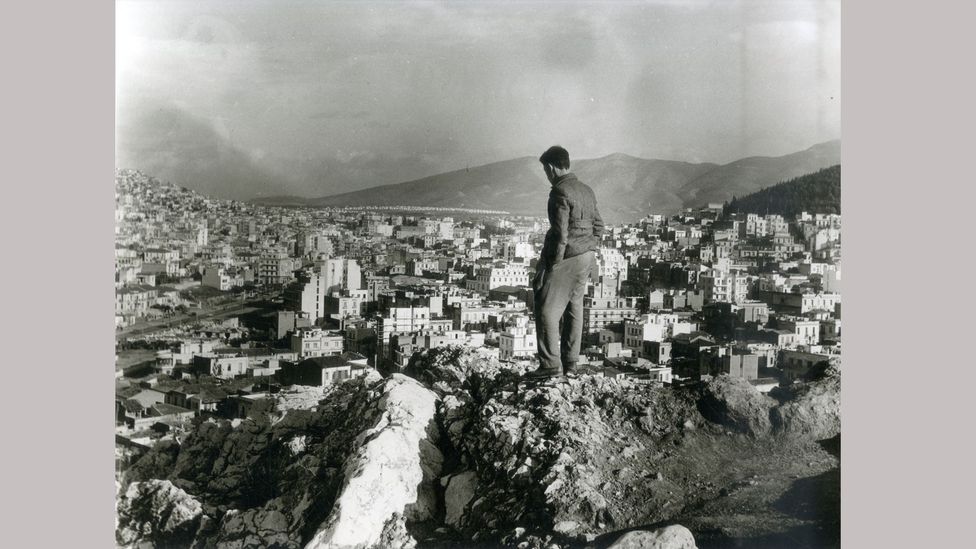

Expansion of Athens, 1950s (Credit: Benaki Museum, Costas Megalokonomou Archives/ Image from Builders, Housewives and the Construction of Modern Athens by Ioanna Theocharopoulou)

Thousands of unemployed Greeks found work as builders, making enough money to send remittances back to their families in the provinces. The state, meanwhile, could focus its resources on building up other sectors of the economy such as infrastructure, agriculture and tourism. Between 1950 and 1977, the Greek economy grew by 7.7% each year (only Japan recorded higher GDP growth). Construction was one of the main drivers of this boom. The system also managed – very successfully – to diminish the political polarisation in Athens.

“There are some who say that the end of the Civil War took place with antiparochi,” says Panos Dragonas, “because antiparochi was the system that transformed the polarised society of the 1940s into a wide middle class, so there was no reason for conflict anymore. Instead of a highly polarised city with expensive, bourgeois districts in one area and slums in another area, what happened was that the upper-middle class and the lower-middle class were living together in the same building. This created a social and economic integration that helped obscure the class divisions of post-War Athens.”

Boom time

“The building boom benefited a large part of society, not just the 1%, but the 95%,” adds Ioanna Theocharopoulou, author of Builders, Housewives and the Construction of Modern Athens.“Construction acted as a tool, a way for those who flooded the city from the countryside not only to create shelter for themselves but to also make a living and even within a generation, move from an agrarian way of life that was harsh to a new urban middle class.”

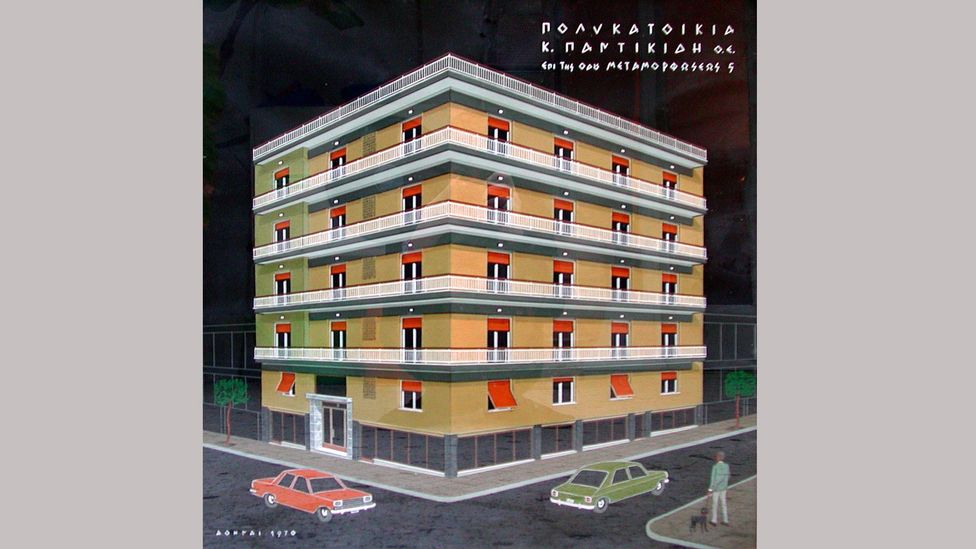

Design for a building in Athens, 1970, designer unknown (Credit: Image from Builders, Housewives and the Construction of Modern Athens by Ioanna Theocharopoulou)

In short, everybody was making money, everybody was getting homes and everybody was, theoretically, able to escape the grinding poverty of the countryside, and start a new life in the city. The luxury of preserving Neoclassical architecture simply never entered into the equation.

A further 680,000 internal migrants arrived in Athens during the 1960s, with the city’s population reaching 2 million by the mid-1970s. By this point, Neoclassical Athens had almost entirely vanished. In its place, a sea of ugly, low-rise concrete apartment blocks stretching as far as the eye could see.

Nature and history intersect in surprising and beautiful ways

It was around this time that Athenians started to feel guilty about what they had done. The speed of development, lack of administrative oversight and absence of architects had contributed to the ad hoc ugliness and featureless sprawl. Under antiparochi, most polykatoikies were constructed with a view to maximising profits, without any thought given to the aesthetic value. If Athens looks like it was created quickly, with no central planning, that’s because it was.

‘No Signal’ mural in Athens, 2013 (Credit: Image from Builders, Housewives and the Construction of Modern Athens by Ioanna Theocharopoulou)

Consequently, the state attempted to atone for its absence from housing policy. Preservation laws were placed on surviving Neoclassical buildings, most notably in Plaka, the colourful Neoclassical neighbourhood beneath the Acropolis which had thus far avoided destruction mainly due to its proximity to the city’s major archaeological sites. In 2006, a property tax was introduced which made antiparochi financially unviable for most individuals. For the first time in its modern history, the population of Athens actually started to decline. In this climate, construction effectively came to a halt. Antiparochi was dead – for now.

The challenges of modern Athens have befuddled architects looking to create a future for the city. Athens is so high density and so consumed by its polykatoikies, that it makes creating new buildings a challenge. Most resources are instead channelled towards renovating the polykatoikies themselves, which are often in poor condition. The lack of opportunities for building has forced young Athenian architects to reconsider their role in the city.

The sight of the Parthenon, rising imperiously out of the chaos, is genuinely breath-taking

The ancient Acropolis and the Parthenon overlooking Athens are an extraordinary sight (Credit: Alamy)

Haris Biskos is part of a new generation of architects taking up the challenge of designing Athens’ future. For him, it’s not architecture but urbanism that motivates young architects today – and he sees an opportunity in the city’s much-maligned antiparochi culture.

“How can you take the idea of antiparochi and transform it into a modern concept that meets the contemporary challenges of Athens? Can you give an empty area to people, and take back a dynamic public space? So we gave an arcade with empty shops to people, and they turned it back into vibrant workshops and assembly spaces.”

He often partners with local authorities, and points out that the modern Athenian is much more aesthetically conscious than in the past. “The problem was lack of regulation, not antiparochi,” he says. “The idea of exchange is one that architects should work on. It’s not about building things, but about creating systems. For me this is the future of architecture in Athens.”

The Plaka district of Athens is ‘serenely beautiful’ (Credit: Alamy)

Walking through Athens today is an odd feeling. The sight of the Parthenon, rising imperiously out of the chaos, is genuinely breath-taking, no matter how many times you have seen it. The neighbouring hills form what is effectively an urban forest within the city centre, one in which nature and history intersect in surprising and beautiful ways. Plaka – though touristy in the extreme – is still serenely beautiful.

In recent years, a series of tasteful restorations and pedestrianisation has added much character to the city centre. Several new parks have been proposed. An ambitious plan to unearth the ancient Ilisos river, which was concreted over during the antiparochi period, is gaining traction. Meanwhile, the energetic charm of the city’s street life continues unabated.

And yet, as you leave the heights of the Acropolis, and drop down into the concrete caverns of Athens, the unshakeable feeling you are left with is not relief at what was saved, but sadness at what was lost.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.