The Frankenstein's monsters of the 21st Century

Novelists are exploring man-made, human-like beings in a new wave of AI fiction. John Self speaks to the authors, including Kazuo Ishiguro, and asks what these sentient machines tell us about being human.

Artificial intelligence always seems to be about 30 years away: for decades, futurists and scientists have been predicting within a generation the development of human-like intelligence in machines. Given that even self-driving cars can't yet look after themselves, it doesn't seem as though we need to worry about being ruled by sentient machines for a while yet. In fact, the only place where man-made humans have thrived is in the world of fiction.

More like this:

Two hundred years ago, 20-year-old Mary Shelley won a bet with her future husband Percy Shelley and his friend Lord Byron to write a horror story: she created Frankenstein, the story of a Genevan scientist who created artificial life – and regretted it for the rest of his days. Shelley created more than she knew: her story is not just considered to be the first science-fiction novel, but has spawned an army of monstrous descendants.

What is it that continues to draw writers, particularly those who don't usually write science fiction, to create artificial humans? How do writers use these characters to tell us about ourselves? What does the 21st-Century Frankenstein's monster look like?

Alamy

AlamyIt's worth reminding ourselves first what Frankenstein – slandered by Hollywood into a monster-mania freak show – is actually about. (One definition of a classic, after all, is a book that still has the power to surprise you.) In the novel, inquisitive student Victor Frankenstein gives life to "the creature", which then absconds and sets about a rampage of murder. "His soul is as hellish as his form," concludes Victor, rejecting his creation, "full of treachery and fiendlike malice". But the reader is forced to reshape their view of the creature when he speaks directly of his experiences: his longing for human society, his perpetual rejection, his turning against first himself – "I am solitary and abhorred… I was not made for the enjoyment of pleasure" – and then against Victor's family, as a surrogate for his despised creator. "If I cannot inspire love I will cause fear."

We learn that the real monster is both of them: Victor for his cruel refusal to make a female companion to assuage his creation's loneliness, and the creature for the trail of death he leaves before heading for his final solitude on the Arctic seas.

Ever since Shelley set the trend, other writers have enthusiastically explored quasi-human creations, all the better to explore what makes us human. One of the latest is Paul Braddon, whose debut novel The Actuality was published last month and has already been optioned for a TV series by BBC Studios.

Sandstone

SandstoneThe Actuality is set around 150 years from now, and told from the viewpoint of Evie, one of two surviving, highly advanced Artificial Autonomous Beings (AABs), when such creations have been outlawed due to problems with earlier models. She lives in hiding with her human husband, and initially believes herself to be human: "She'd persisted in denying the truth even when the evidence had begun to stack and stack". (Ironically, a very human trait.) The tension in the story comes both from her own growing discovery of her true nature, and from her pursuit by the authorities and her need to flee or fight to protect her existence.

Braddon tells BBC Culture that he sees parallels between Frankenstein and Evie's story. "Like the monster, she becomes an outcast; people fear her because they assume the worst. Like Frankenstein's monster, in theory Evie has the potential to be anything, but is limited by how her maker made her. She has to escape the bonds of her existence."

The Actuality offers a rich contemplation of ethical and philosophical questions about artificial life and intelligence. Where does life begin and end? If an AAB like Evie can simulate consciousness, does she have rights? Conversely, if she kills a real human being, can she be held responsible? In the story Evie is modelled after a real woman and, explains Braddon, "she is regulated by her programming to emulate someone she has never met and behave as they would – her 'unforgiving quest to be second best' – but even so, she must still choose between right and wrong". When Evie is on the run, her decisions "have life or death consequences", says Braddon. "At times it felt that I was making Evie too nice for her own good, but by the end I believe I found enough of her dark side to balance things out!"

A chaotic blend

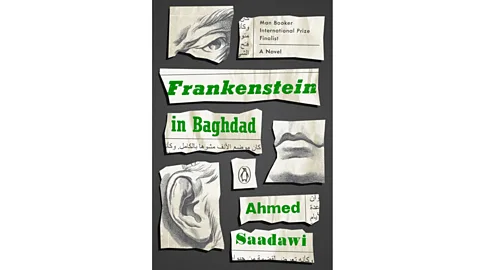

Of course for an artificial human to be realistic, to match the rest of us, it has to be a chaotic blend of right and wrong, to find its way by picking through the wreckage of its own bad decisions. Another recent example is the creature called the Whatitsname in Ahmed Saadawi's Frankenstein in Baghdad, which was shortlisted for the International Booker Prize in 2018. In war-torn Iraq in the early 2000s, a junk dealer called Hadi assembles a being from the body parts of people killed in the conflict. "I made it complete so it wouldn't be treated as rubbish, so it would be respected like other dead people and given a decent burial."

Bloomsbury

BloomsburyBut the Whatitsname goes missing, and sets about a retributive rampage, like the original Frankenstein's monster. Saadawi's vision is satirical, the blackest of comedy about tit-for-tat killings and the dehumanisation of people in war: the creature finds that as it avenges each death, its corresponding body parts fall off, so it has to kill more people to replace them. Eventually "he knew his mission was essentially to kill, to kill new people every day, but he no longer had a clear idea who should be killed or why". This most modern of monsters even gives a press conference to justify his actions and mock his creator, a child rebelling against his parent: "You were just a conduit, Hadi. Think how many stupid mothers and fathers have produced great men in history."

For Saadawi, the monster is "the mirror image of us as a whole", reflecting how people in Iraq "became either active participants in the killing or indifferent toward scenes of death". Speaking to BBC World Service's The Cultural Frontline, he said that "we like to see ourselves as victims and see others as aggressors, but in this case [the Whatsitsname] was both the aggressor and the victim" – much like Victor Frankenstein's creation – and he represents the "monster inside everybody – not just in Iraqis but everywhere".

The stitched-together creature, in other words, is a patchwork of our best and worst human characteristics. How could it be otherwise? In Frankenstein, the human society that rejected the monstrous-looking creature triggered his killing spree. Paul Braddon had this in mind too when writing The Actuality: "I do have concerns as to how we as humans would interact with such a class."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesCentral to these stories is not only the relationship of the artificial human to their creator but also the purpose of their creation. Victor Frankenstein made his creature out of the noble spirit of scientific inquiry. (We never find out how Frankenstein made his monster, ostensibly because he doesn't want anyone to emulate his mistake, though it handily absolved Mary Shelley from having to dream up the mechanics.) In The Actuality, on the other hand, the driving forces behind Evie's creation are less honourable. No spoilers but "it all comes down to what motivates mankind", says Braddon, "which could be reduced in the simplest sense to money, power and sex". Can a woman be made by men? Can she consent to sex? Like all of us, Evie is constrained by the circumstances of her birth.

Sex, indeed, is something no human – or artificial human – story would be complete without, and Jeanette Winterson's 2019 novel Frankissstein makes the most of it, with her typical boldness and wit. Winterson's story splices the origins of how Mary Shelley came to write Frankenstein with an alternative present where artificial humans are being built as sexbots.

Winterson, whose prescience means she was writing about artificial sex ("teledildonics") as long ago as her 1992 novel Written on the Body, is not surprised to see humanity barrelling down the path she predicted. "Because we are profoundly stupid," she has said, "we are going to share the planet with a self-created non-biological lifeform smarter than we are. Well done, human race!" But Frankissstein, perhaps uniquely among the AI novels featured here, is very funny. "The world is so dire at the moment, it's important to make people laugh. It isn't an escapist response, it's a way of managing it."

A more compliant non-human appeared on the bookshelves this month, as Kazuo Ishiguro published Klara and the Sun, his first novel since winning the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2017. Klara is an Artificial Friend, a quasi-human device created to prevent teenagers from becoming lonely. As with Evie's story, Klara's is written from the non-human viewpoint.

Alamy

AlamyHow did Ishiguro go about this? "Well," he tells BBC Culture, "I just kind of plunged in rather recklessly to see what would happen". He laughs. "But I've always been drawn to slightly oddball narrators." As a narrator, he says, Klara has "a great advantage in being technically not human. So it puts these questions very naturally in the reader's mind: What does it mean to be human? What do humans mean when they say they love somebody? So it's a very good way of being able to ask those questions without seeming contrived or pretentious."

And although Klara is less likely to go rogue than the other creations described here, Ishiguro similarly uses his Artificial Friend to represent the full breadth of human life, just as he did with clones in Never Let Me Go. As her story proceeds, Klara undergoes a real-time process of learning about how humans think and feel. "This is a narrator that could hold, I thought, an incredibly complex mixture of sophistication and naivety," Ishiguro says. "And I thought you could get an entire human lifespan into her approach, just within the few years that this machine existed. She could go from being a toddler to being a teenager to be something like a parent, to empty nest syndrome, where she feels she's done what she's supposed to do."

Penguin

PenguinThe modern Frankenstein's monster, then, is as diverse as the humans who create them: as fictional devices, they are vehicles for satire, thriller, horror or allegory, even if, as Ian McEwan puts it in his android-affair novel Machines Like Me, they ultimately represent "a monstrous act of self-love". But in all cases, they stand or fall on how real humans treat them, which is something their programming and AI learning can never overcome.

The Turing Test for artificial intelligence says that if we cannot tell the difference between an artificial mind and a human mind, we should treat the artificial mind as a human mind. But the human characters in these novels – driven by very human prejudice – don't do this, fearful of the creatures' otherness, or just resentful of their perfection. In Shelley's novel, Frankenstein's monster had the potential to be better than most of us – he looked up to the peaceable lawmakers of Plutarch's Lives as his model – but was driven to the very lowest of human impulses by how others behaved towards him.

Alamy

AlamyThis is all terrible news for artificial humans, but good for literature: it's our moral uncertainty that makes not just these stories live and thrive. Creatures who are not quite like us can enhance our understanding of ourselves, even if the results aren't always pretty. In fact in McEwan's Machines Like Me, the android character Adam comments that in a world run by artificial humans, without emotional turmoil, without the eternal mysteries of the human heart, most literature would be irrelevant and superfluous. Just as well it's not going to happen for around 30 years, really, isn't it?

Klara and the Sun by Kazuo Ishiguro is published by Faber; The Actuality by Paul Braddon is published by Sandstone Press

Love books? Join BBC Culture Book Club on Facebook, a community for literature fanatics all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.