What our science fiction says about us

The Wandering Earth

The Wandering EarthDifferent visions of the future are springing up around the globe. Tom Cassauwers explores what these movements reveal about the places in which they appear – including China, Russia and Africa – and how imagining alternative realities can be subversive.

The sun has cooled down and Earth has become uninhabitable. Only one solution remains for humanity: flee beyond the solar system. This is the premise for The Wandering Earth, and the movie could easily be a Hollywood blockbuster. The trailer even has Inception-esque foghorns. Yet this isn’t a US movie with an all-white cast, it’s the Chinese adaptation of a science fiction book of the same name by star writer Cixin Liu. It’s the Chinese who are saving humanity here, not the Americans.

More like this:

- Why Children of Men has never been as shocking as it is now

Well-known artistic depictions of the future have traditionally been regarded as the preserve of the West, and have shown a marked lack of diversity. Yet new regions and authors are depicting the future from their perspectives. Chinese science fiction has boomed in recent years, with stand-out books like Cixin Liu’s The Three-Body Problem. And Afrofuturism is on the rise since the release of the blockbuster Black Panther. Around the world, science fiction is blossoming.

Alamy

Alamy“Science fiction is now a global phenomenon,” says Mingwei Song, Associate Professor at Wellesley College, specialising in Chinese sci-fi and literature. “This has been one of the most remarkable developments of the genre because it transcends this Western and particularly Anglo-American domination of the genre.”

And the new movement is wide-ranging, including everything from Russian science fiction – with a history reaching back into the 19th Century – to Afrofuturism, a movement rooted in experiences of black oppression. It covers Chinese books dealing with revolutionary history and aliens, to futurist Mexican movies about migration and free trade.

“Right now the most interesting science fiction is produced in all sorts of non-traditional places,” says Anindita Banerjee, Associate Professor at Cornell University, whose research focuses on global sci-fi. “But this phenomenon, which is now making its voice heard from areas like China or Africa, also has a much longer history that precedes today’s boom.”

Subversive fiction

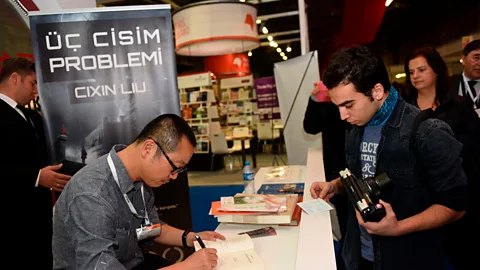

Currently, Chinese science fiction is becoming increasingly popular in the West, thanks to English translations of writers like Cixin Liu and Hao Jingfang. Nevertheless, there was a long history of sci-fi preceding them.

Alamy

AlamyThe genre went through three waves in the country: one after the fall of Imperial China in 1902; one after the Chinese revolution in 1949; and the current ‘new wave’ which started in the 1990s, when the country pushed forward in its rapid pattern of development. “In the 1990s a new generation of writers began to emerge, and among this generation, Liu Cixin is the most important author,” says Mingwei.

First released in 2006, Cixin’s The Three-Body Problem is credited with pushing Chinese science fiction into the mainstream. In 2014 it was translated into English and a year later it won a Hugo Award, the Oscars of science fiction. The story deals with an astrophysicist who gets involved with secret government research during the Cultural Revolution, inadvertently inviting aliens to earth.

The Wandering Earth

The Wandering EarthChinese science fiction is seen as a reflection on the narrative of a rising and rapidly modernising China, which is also becoming increasingly prevalent in the West. But the genre also deals with repression of free speech, often showing dark, unseen sides of reality. In the case of Cixin Liu, this often means parallel realities and challenging physics. But, in turn, the book Folding Beijing by Hao Jingfang shows a tightly hierarchical future Beijing in which the Earth spins around to give three social classes variable amounts of Sun.

“This new wave of science fiction has a dark and subversive side that speaks either to the invisible dimensions of reality, or simply the impossibility of representing a reality dictated by the discourse of a national dream,” says Mingwei.

The Three-Body Problem and Chinese science fiction in general often feature controversial subjects. The opening scene of The Three-Body Problem, for example, depicts the lead character’s father being lynched in a collective struggle session at the height of the Cultural Revolution.

“I’m always amazed by the continued prosperity of the genre,” says Mingwei. “Some of it is very subversive and provocative. But so far they haven’t been censored. My theory for why it continues to grow is that it isn’t protest literature. It’s a literary genre that uses the imagination to explore unseen realities. But it doesn’t directly challenge the Chinese government.” And these unseen realities are key. “Science fiction depicts the invisible part of Chinese reality that is hidden behind the glorious image of China on the rise,” he says.

Making the invisible visible

Another artform looking at unseen realities is Afrofuturism. “If you look at depictions of the future, from Blade Runner to The Jetsons, the future is often very white, and people of colour are often missing,” says Susana Morris, Associate Professor at Georgia Institute of Technology specialising in Afrofuturism. “Afrofuturism re-imagines what a futurist landscape would look like with blacks at the centre.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAfrofuturism reaches back to when W E B Du Bois wrote his 1920 short story The Comet, in which the entire human population is killed, except for a black man and a white woman. The best-known example of Afrofuturism is 2018 superhero movie Black Panther, depicting Wakanda, a non-colonised African country that has been able to develop on its own terms, and which owns the world’s most powerful resource: Vibranium. This background provides the canvas on which a futurist, black society is depicted in the movie and the accompanying comic books written by Ta-Nehisi Coates.

Yet Afrofuturism reaches beyond superheroes. “People often think Afrofuturism is a genre, while really it’s a cultural movement. It isn’t just black science fiction. It’s a way for black folks across the diaspora to think about our past and future,” says Morris. As such, Afrofuturism includes substreams like fiction, movies, art and fashion – Morris notes how Beyoncé occasionally uses Afrofuturist imagery.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn the realm of written fiction, the Nigerian-American writer Nnedi Okorafor's Binti stands out. The 2015 book depicts an African tribe modelled on the Namibian Himba people, 1,000 years into the future. They are an advanced yet isolated community, and in the book one of their experts in advanced mathematics gets sent to an interstellar university where the story unfolds. “It’s a great story that mixes tradition and innovation,” says Morris.

Afrofuturism is a genre that isn’t necessarily associated with one country or region, but is practised by black people from all across the world, a diaspora in Morris’s terms. For this diaspora, the interaction with tradition is key: Morris refers here to Sanfoka, a symbol from the Akan people in Ghana, generally stylised as a bird that looks backwards while moving forwards. “Afrofuturism reveals a dynamic relationship between innovation and tradition that is at the heart of the diaspora”, says Morris. “It looks back while moving forward.”

Bolsheviks in space

Russian and Eastern-European sci-fi has a long history stretching back to the 19th Century: it produced key writers in the canon like Russian writer Yevgeny Zamyatin, who wrote the 1924 novel We, and the Polish Stanislaw Lem, who was a key influence on US science-fiction. Even early Bolsheviks like Alexander Bogdanov wrote science-fiction (in his 1908 novel Red Star he notably depicted a Mars inhabited by socialists).

Alamy

AlamyThe experience of Sputnik was crucial. When, in 1957, the Soviets were the first to send a satellite around the Earth, it launched an explosion of science fiction and led to the re-discovery of older sci-fi works. Previously repressed by socialist realism, Soviet society was catapulted by the launch of Sputnik into a futurist perspective. Citing sci-fi expert Istvan Csicsery-Ronay from DePauw University, Banerjee claims this caused a “science-fictionality of daily life” in the country.

This even stretched into movies. The 1972 film Solaris by Andrei Tarkovsky was hailed as a counterpart to 2001: A Space Odyssey, while Stalker, another movie by Tarkovsky and an adaption of 1971 novel The Roadside Picnic, depicted the crossing of a mysterious nuclear wasteland. Interestingly, decades later it inspired the present-day Ukrainian videogame series S.T.A.L.K.E.R.

Alamy

AlamyThe Russian experience, particularly under the Soviet Union, ties back into the current rise of non-Western science fiction. For Banerjee, this relates to her personal story. “I grew up in eastern India, in coal-mining country,” she says. “This place was not very culturally rich, but one set of books that were accessible and cheap were translated Russian books. And the Space Race saw a renaissance of science fiction writing in the Soviet Union, which, together with their classic science-fiction, was translated and disseminated into the Global South. Even into rural India.”

Russian sci-fi in this way served as an incubator for a new, global science fiction. “In the works of Cixin Liu, you can for example see references to Soviet science fiction,” says Banerjee.

From the West to the rest?

This rise of global science fiction questions how we think about the evolution of the genre. In the past, it was seen as spreading from Western centres to the rest of the world. “The traditional view of science fiction was that it expanded parallel to the spread of industrial capitalism around the globe,” says Banerjee. “So it supposedly went from the West to the rest, because that’s where industrial capitalism first took hold. Now this perspective is being challenged, and we are thinking about what happened outside the West.”

Alamy

AlamyAlthough not all non-Western science fiction is political, imagining alternative futures can serve as a tool for mobilisation and activism. “What we find in some science fiction from the global South is a recognition that a universalised, neoliberal model of society and culture are unsustainable,” says Banerjee. She refers for example to Sleep Dealer, a 2008 Mexican sci-fi movie that depicts a future where the US has closed its Mexican border, but in which Mexicans remotely control the robots that replaced their labour inside the US. The movie reflects on issues like free trade and migration in a futurist fashion.

But beyond a global reflection on resistance, non-Western science fiction also taps into a worldwide consciousness – helping it conquer audiences beyond their respective home markets. “Chinese science fiction doesn’t just appeal to Chinese people,” says Mingwei. “Because it touches upon questions that are shared by humanity, for example the survival of the human race and how to be a moral person in extreme circumstances. Which are fundamental questions every human needs to think about in our contemporary world.”

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.