The business of eating bugs

Taylor Weidman

Taylor WeidmanThey’re a rich source of protein and use a fraction of the resources of beef or poultry. If people can get over the ‘ew’ factor, edible insects are poised to become a massive industry.

Taylor Weidman

Taylor WeidmanTiny critters are becoming big business in the food and agriculture sector, and for good reason.

Westerners are increasingly seeing edible insects as a sustainable form of a ‘complete protein’. Insects offer all nine amino acids essential to the human diet, similar to animal proteins.

But it’s not just about nutrition. The environmental sustainability of insect farming poses a compelling reason to embrace entomophagy – the practice of eating insects. Insects can offer as much protein as animals when produced on a large enough scale, but need far fewer natural resources than beef, pork or poultry production and also emit a fraction of the greenhouse gases.

This is big news for the agriculture sector, which is not only the world’s biggest land and water user but also one of the most significant greenhouse gas producers.

Taylor Weidman

Taylor WeidmanMarket signs are promising. According to a report by US-based Global Market Insights, the edible insect market is projected to soar from $55m in 2017 to roughly $710m by 2024, fuelled by growing demand for high-protein and convenience foods.

Grasshoppers, locusts and crickets are the most popular for use in protein-rich flours, bars and snacks.

Another area that could be revolutionised is animal feed production, which represents a major chunk of the agricultural sector. Insect farming offers highly nutritious feed but requires far fewer resources than growing feed crops including soy, corn and grain.

Responding to the industry’s potential, a newly-established US trade body (the American Coalition for Insect Agriculture) is currently lobbying the FDA and USDA to recognise insects as food and to set production standards. In the EU, the Novel Foods Rules of 2018 have begun to establish a legislative framework for including insects in mainstream food manufacturing.

Taylor Weidman

Taylor WeidmanEating insects is nothing new in many parts of the world. The UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) estimates that insects are part of the regular diet of roughly two billion people globally.

In Thailand, the edible insect hub of Asia, eating insects originates in the north-eastern rice-farming Isaan region, where they are served as side dishes in local cuisine.

Until recently, the only Westerners sampling these delicacies were curious tourists. But now Thailand is eyeing the West for exports of edible insect products. In 2017, the Thai Ministry of Agriculture became the first in the world to implement Good Agricultural Practices for cricket farming, setting out guidelines for safe and efficient production. Although the majority of Thailand’s insect farms are small-scale operations, researchers and investors are assessing ways of scaling up production.

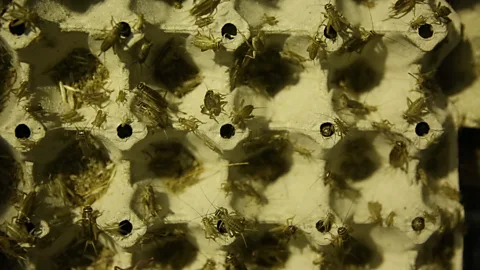

Cricket Lab, established in 2016 in Chiang Mai, is researching automated processes. The farm currently has the potential to produce 3.5 tonnes per month, says co-founder Radek Hušek. All it needs is the demand.

Taylor Weidman

Taylor WeidmanAlthough the FAO say the most commonly eaten insects across the globe are beetles and caterpillars, it is the cricket that has gone mainstream in the developed world.

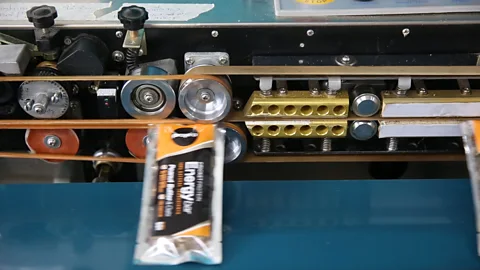

While insect burgers and mealworm noodles can be found in some European supermarkets, cricket-flour protein bars are becoming commonplace across Europe and North America.

Taste or common perceptions may play into this preference. But for reasons that industry players can only conjecture, crickets seem more palatable to Westerners than any other bug.

“It’s like Jiminy Cricket. Lots of times, crickets are like a fairy tale character,” says Hušek. “Cockroaches have the potential to be an insect flour – they’re really high in protein – but cockroaches have always had a negative perception. The image of a cricket jumping over grass in a hay field is better to imagine than a cockroach ground into flour and served.”

Taylor Weidman

Taylor WeidmanMany other insects, such as mealworms, are just as rich in protein as crickets and might be easier to raise under different circumstances, such as in cold climates.

However, there is still a very real ‘ew factor’ that presents a marketing challenge in the West.

“Trying to get anyone to eat a cricket – it’s like you have to multiply that by two to get them to eat any kind of worm,” says Abe.

Taylor Weidman

Taylor WeidmanThere’s a saying in the industry: crickets are the gateway bug – Michi Abe

Taylor Weidman

Taylor WeidmanMichi Abe, an American living in Chiang Mai, became the first insect protein bar manufacturer in Thailand in 2016 when he began producing ProPro bars. They contain crickets that have been dried and ground into flour. Cricket is known for its high protein content as well as iron, calcium and vitamin B12.

His target market is “healthy, active, fitness-oriented people”. Abe sells mostly domestically, but most of his customers are non-Thais. That’s because although Thais are comfortable eating insects, they eat them as deep-fried beer snacks, says Abe. “There’s no association with health or wellness. It doesn’t really compute as to why there are crickets in these bars.”

In the West, however, health-conscious subcultures such as Crossfit members are buying into entomophagy. One of the selling points for vegans is the belief that crickets don’t have pain receptors. Although there hasn’t been enough research to verify this, more scientists are beginning to research insect welfare.

Taylor Weidman

Taylor WeidmanArnold van Huis, professor of tropical entomology at Wageningen University in The Netherlands, and one of the world’s leading experts on entomophagy, says that scientific interest in edible insects has experienced tremendous growth over two decades. But especially in the last two years.

More academic papers have been published on edible insects in 2016 and 2017 than in the previous 10 years, he says.

The main factor driving this interest is environmental sustainability. “Regarding health or nutrition, insects are similar to common production animals. The main benefit is environmental,” says van Huis.

Taylor Weidman

Taylor WeidmanAs the global diet becomes more westernised, the demand for meat has increased. But this demand for livestock and the feed that sustains them are major contributors to global deforestation, pollution, water shortages and greenhouse gas emissions.

And while farming insects for human consumption has the potential to replace some demand for animal protein, agricultural leaders believe insect farming can have the biggest environmental and economic impact as animal feed.

“The EU allowed insects to be used in agriculture last year,” says van Huis. “We also expect the US and Canada to use insects as feed. So this is really big. The companies that are looking into this have received quite significant investments.”

An additional benefit of insect farming is that insects can be fed on biowaste, contributing to a circular economy.

Taylor Weidman

Taylor WeidmanThe FAO is focusing on entomophagy as a way of alleviating food shortages and malnutrition. But without major R&D investment, high production costs remain a barrier. While some large insect farms, like ProtiFarms in The Netherlands, have created low-cost production processes, these remain largely proprietary.

But Cricket Lab believes insects could be a viable way to help malnourished communities. Radek Hušek says its mission is to promote insects as a viable protein source, research low-cost production methods and license those methods to small farmers. The company aims to make insect farming as cheap as raising chickens.

“Once a system of efficient farming is found, insects can really help the whole economy of resource use,” Hušek says. “It can be low investment and very efficient in getting proteins to rural areas and countries.”

Taylor Weidman

Taylor WeidmanIf you prepare insects well, they look good to eat – Mai Thitiwat

Taylor Weidman

Taylor Weidman“When I started giving presentations 20 years ago, almost nobody knew that you can eat insects. Now, when I ask the crowd who has eaten an insect, many hands go up,” van Huis says. “Insects are becoming trendy. We have it in supermarkets in The Netherlands, with items like burgers, but they are not very tasty. For it to have a future, you really have to make it very tasty.”

In Bangkok, executive chef Mai Thitiwat is addressing this very need with Insects in the Backyard, a restaurant he opened in the fashionable Chang Chui creative hub in 2017.

Mai did a year of research to understand the different farming and production processes of insects, their nutritional benefits, sustainability, flavour profiles and uses as food. He drew from traditional Thai cuisine but used his skills as a trained fine dining chef to create a menu of French and Italian-style cuisine with insects at the heart of each dish.

Taylor Weidman

Taylor WeidmanThe restaurant has excited a crowd eager to try new things, and many are finding themselves up to the challenge of trying silkworm tiramisu or lobster and grasshopper risotto. The restaurant’s best-selling dish is the giant water beetle ravioli.

“If you prepare insects well, they look good to eat,” explains Mai. “If I prepare a whole chicken with its feathers and nails and roast it and serve it to you, then you won’t want to eat it… It’s the same with insects.”

While it may take decades, Mai believes entomophagy will become mainstream in the future.

Insects in the Backyard purports to be the only fine dining entomophagy restaurant in the world – but it's not likely to stay that way for long.

Taylor Weidman

Taylor Weidman