What we talk about when we talk about ‘humanness’

One of the more curious promises of technology in the 21st century is that it can confirm someone’s humanity. It sounds counterintuitive. But as AI becomes an established feature of our daily lives, and bots, deepfakes and scams proliferate, the question of how to verify that an entity is a person and not a machine has become central to digital identity, authentication and the quest to digitize anything and everything.

In a recent article for Wired, author Kate Crawford says that “in 2025, it will be commonplace to talk with a personal AI agent who knows your schedule, your circle of friends, the places you go. These anthropomorphic agents are designed to support and charm us so that we fold them into every part of our lives.”

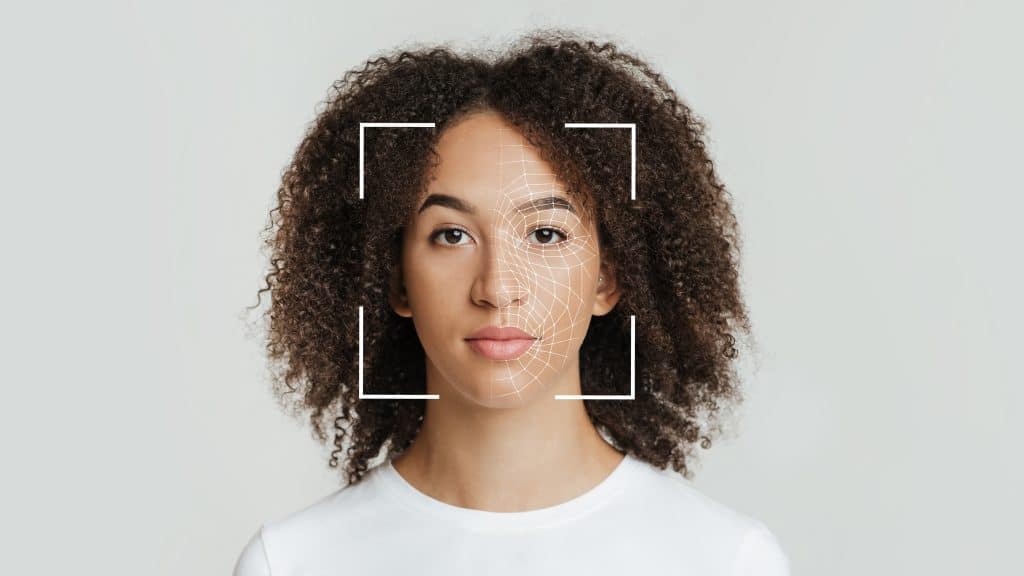

Accordingly, an industry has grown to make sure we know who’s real and who’s not. The question has been framed as “Proof of Personhood” (PoP), and biometrics is central to its operations. A key feature of biometrics (and what adds an element of additional risk if they are stolen) is their uniqueness. Your face, fingerprint or iris biometrics are like no one else’s. As such, it provides the “one and one only” element of digital personhood – which, after all, wants not only to distinguish you from a machine, but also from other identities.

But the technical and technological problems of personhood come with extra baggage. In dealing with the language of fundamental rights and verified humanness, firms are treading ethical grounds that have implications beyond the digital ID industry. Firms are coming at the problem of how to preserve personhood – in data and in language – from different perspectives, but with a similar, massive goal: to service everyone on planet Earth with a unique digital identity.

Civic aims to define digital identity with personality

Among those positioned to make an impact is Civic. Founded in 2015 in San Francisco, Civic uses a tokenized identity model for identity management that prioritizes privacy. Its website says its user management tools allow clients to “deploy seamless onboarding and authentication in just a few lines of code.” It prevents so-called Sybil attacks, which involve gaining an unfair advantage over a network by controlling multiple accounts.

But, in a recent email interview with Biometric Update, the company says its primary objective is “to be the world’s most trusted identity solution, used by billions every day.”

Civic’s website says it is “working toward a world where identity is not only defined by documents, but also personality. Where the unique expression of an individual contributes to the security of a digital identity that they own and control.”

While others deal in PoP, Civic’s notion of a ‘digital personality’ shows how the language of being is fusing with the language of digitization. The company believes identity and its attached personality are “a synthesis and expression of three primary areas: who you are, what you have, and what you’ve done.” Like identity, digital personality “may be expressed in anonymous, pseudonymous or fully proven ways depending on the objective.”

Who you are could be anything from a name claimed on a social media platform to verifiable third-party attested data like a government-issued passport.

What you have refers to private cryptographic keys, “which can be verified on-chain can then be correlated to ongoing ownership through mechanisms like proof of wallet ownership.” Identity verification is a use case; so are NFTs.

What you have done is identity attached to traceable histories – for instance, proof of “membership in organizations like decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs) via voting history, trading volumes and participation in any other on-chain activity. The more demonstrable history you have, the more you build trust with potential counterparties, but without needing the middle layer of things like credit bureaus.”

Civic Pass, Civic Auth offer secure blockchain gateway, SSO

Civic, which works with FaceTec biometrics, offers two main products. In the most basic terms, its Civic Pass blockchain product “provides users an entry point to the verifiable internet, enabling developers to implement user verification and access control in applications and smart contracts.”

“What this means,” the company says, “is that developers can choose to leverage Civic’s identity verification offerings like Liveness, Uniqueness or Document Verification as a gating criteria, or issue on-chain passes based on their own criteria. In this way, users’ unique biometrics or verifiable data (i.e. who you are) can be tied to wallet ownership (i.e. what you know – the private key).”

The Civic Auth product “further lowers the barriers to entry for developers and users to present a familiar login experience, while optionally pairing it with the power of the verifiable internet.” The provided example is a developer choosing to “simply ask their users to log in with Google or add an embedded wallet and issue an on-chain Civic Pass to gate access to any smart contract using the Civic Auth toolkit. Later, the developer could choose to add biometric checks or other authentications.”

In other words, “Civic Pass provides secure, permissioned access to on-chain assets while Civic Auth offers single sign-on for identity verification.”

In a recent interview with the Metaverse Post, Chief Product Officer JP Bedoya summarizes further: “we developed a proof-of-personhood solution that links one human to one wallet. Using biometrics, like a video selfie, we create a unique 3D facial map to ensure only that individual can access their account.”

Digital identity and PoP will converge but won’t be synonymous

So far, so good: everyone likes secure identity verification and biometric authentication. But the picture that emerges raises questions about where “digital identity” ends and digital “proof of personhood” begins. Civic believes there will be “a convergence of these two concepts,” but doesn’t see “those terms as becoming synonymous in all cases.”

One may not have to prove personhood for some uses of digital identity, while others – for example, social media companies – will require measures to ensure that accounts posting on their platforms are run by actual people.

Civic says that “overall, in the next 5-10 years we expect that everyone will have variants of their digital identities that are used at various times (e.g. anonymous, pseudoanonymous, transparent), some of which will require proof of personhood and some of which will not.”

The inclusion piece is key. “It is important to ensure that tools developed to establish digital personhood be widely accessible, well supported, and with outlet processes to allow for equal and fair access to economic and social products and services.” Again, we are to understand that PoP is a way for technology to enable human participation in digitized human affairs.

AI agents may not be human – but we think they can have identities

Civic is confident enough in its mission to know where to draw the line between people and agglomerations of data. It says that “personhood is an inalienable human right which should not be confused with our digital shadows, which ultimately are simply tools to express that personhood.”

Yet, there are obvious cognitive shifts going on in how we as humans relate to machines and their algorithms, and define ourselves against them. In giving an example of how digital identity and digital humanness diverge, Civic notes “AI agents will have a digital identity and may execute actions on behalf of their owners, but themselves may not have a proof of personhood.”

The implication is startling: algorithms are now understood to have identities, or to possess the ability to have them. The linguistic framework for how we define ourselves is no longer the exclusive property of organic beings. While we have long given cute names to robot toys and recently gotten cozy with our Alexas, the notion that an AI agent can express the same degree of “identity” as a real human is a shift of a different magnitude.

Some proof of personhood providers fixing a problem they caused

There is a paradox in making the simple fact of being human contingent on the very machines from which we must be differentiated. In a certain respect, asking someone to justify and prove their own fundamental understanding of reality is a kind of existential gaslighting, tugging at the basic notion that the real and the digital are separate realms.

Aggravating this is that at least some of those shopping proof of humanness are also responsible for the AI threat in the first place. At present, the most notorious name in both AI and PoP is Sam Altman, who opened the AI floodgates in creating ChatGPT, and is now busy pushing his iris-scanning World ID as a way for people to prove they are not just another product of his popular large language model (LLM).

Digitized identity has major material ramifications

World, Civic and many of the firms offering digital proof of personhood offer altruistic motivations and lofty ideals – most frequently, the notion that identity is a universal human right that should be universally accessible. The world is online; so must we all be, fairly and equally. Projects like the EU digital identity wallet rollout underscore this in practice.

However, the wider implications of AI for the physical world are already emerging. Kate Crawford argues that “so far, generative AI is most significant from an environmental perspective: It is fundamentally reshaping Earth.” Noting that AI data centers are already using as much energy as entire nation-states, she defines AI as a “metabolic technology – burning electricity and evaporating water at an exponential rate to keep the ingestion, digestion and production of data going.”

Meanwhile, World’s founders imagine a world of futuristic tupperware parties where the product is not plastic food storage but iris biometrics and identities collected with spherical, single-use scanning devices called Orbs, which seem destined for the e-waste landfill.

The age of the ‘Humanness Conundrum’

Nonetheless, the material concerns that come with AI may soon be dwarfed by the metaphysical ones. When we define human rights and human culture, language lays the tracks that lead to the future. To take one technological example, before Web 2.0 and the birth of social media, entertainment media was not commonly referred to as “content.” The consequences of doing so have reshaped how we think of ourselves and tell our stories.

Which is to say, once the language of humanness is attached to an algorithm, there may be no getting it back. For those wishing to be human without having to prove it, there’s always life off the grid. The risk is, if a person lives in the forest and nobody’s around to verify it, it mightn’t be thought of as living at all.

Article Topics

AI agents | biometric authentication | biometrics | Civic Technologies | digital identity | digital inclusion | identity proofing | proof of personhood | World

Comments