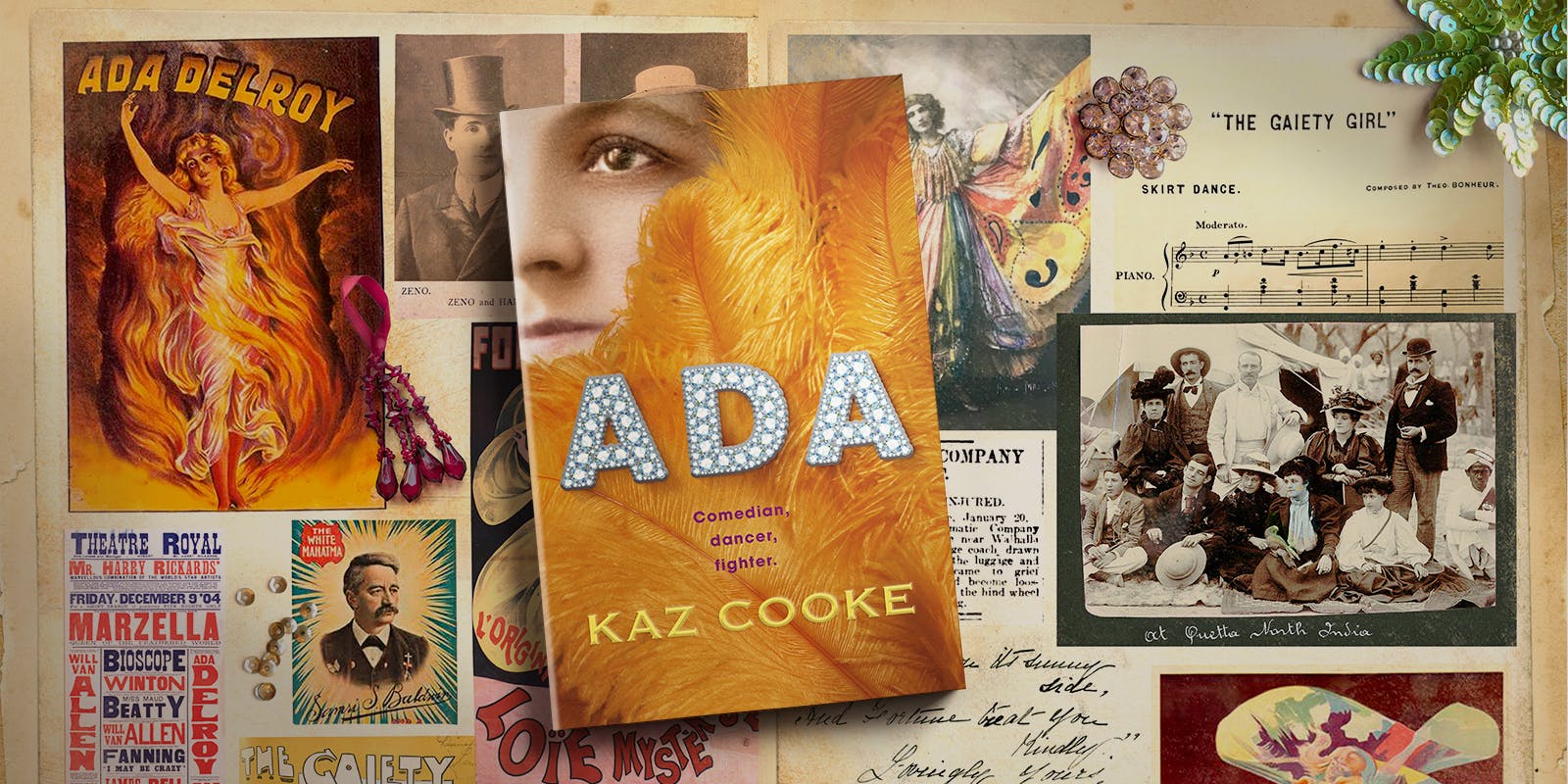

Kaz Cooke reveals the impassioned rummaging to capture Ada Delroy on the page.

It all started when I came across a photo of a woman in a theatre scrapbook while researching a project at the State Library of Victoria on objects people wear to say who they are – from a posh tiara to a footy team jumper. The photo is the one of Ada on page 197 of the book. In it, she’s wearing ‘everything but the kitchen sink’ – a giant hat, ostrich feathers, bows, braid, butterfly brooches, a giant diamond pendant and her name spelled out in diamonds. It was captioned ‘Ada Delroy’.

Image: Ada Delroy, c1895. Photographer unknown, Talma Studios; State Library of Victoria.

I found out she had been a dancer, singer and comedian with her own troupe, the Ada Delroy Company, and I began making a timeline of Ada’s travels and reviews of her shows, using the Australian newspaper archives on trove.nla.gov.au, the National Library of Australia’s digital collection, and the sister archive for New Zealand at paperspast.natlib.govt.nz. Often it took scores of ‘reviews’ to piece together a whole act, sentence-by-sentence; here a name of the song, there a tiny description of part of a comedy sketch costume.

The plan evolved that I would write a novel about Ada’s life – and that everyone in the book, including Ada, would be a real person. I visited the family archivist of a branch of the Bell family troupe’s descendants. Joy Bell from NSW generously shared information on the Bell family, whom had adopted Ada after she was orphaned at 12 in a Lancashire mill town and put her in the family troupe. Joy had wonderful photos of the Ada Delroy Company on tour in India. Other photos were found at the Powerhouse Museum in Sydney, the State Library picture collections, and on one miraculous occasion, on Pinterest.

At the Library I could ‘order in’ from the collection and look at objects from Ada’s era: a 19th century wedding gown (mauve) in two pieces, jewellery, an actress’s back-stage travel iron (heated by a reservoir of methylated spirits that you would light with a ‘vesta’ match or a flaming twist of paper transferred from a dressing-room fireplace). No wonder so many theatres burned down in those days!

I was amazed to see online all the digitised pages of a scrapbook kept by Ada’s rather bonkers boss during the early 1890s, Professor Baldwin. This was a record of the Baldwin tour with the Bells when Ada debuted her signature Serpentine dance in England. (Ada stole all her dances from Loïe Fuller, who became a famous star at the Folies Bergères.) The scrapbook is part of the Houdini collection at the Harry Ransom Centre, at the University of Texas in Austin. More ferreting in the State Library of Victoria turned up the gas bill for the backstage and stage lights from the same year Ada performed at the Bourke St Opera House Tivoli theatre in 1895.

Official archivists in Auckland helped me decipher a relevant, scandalous 1912 divorce case’s exhibit letters, written in a dreadful hand, in purple, soluble pencil and smudged with tears (or whiskey). I consulted modern experts on genealogy, tuberculosis, larrikins, tin-silk frocks and sea slugs. That was all part of the fun for me, flexing my old journalism muscles and just satisfying my own curiosity. I read novels of the time, and histories of clairvoyants, spiritualists and ‘black-face’ minstrel entertainers, and consulted slang dictionaries for Lancashire and 19th century theatre, Australianisms of the day, and the theatre history books by Aussie experts Frank van Straten and Mimi Colligan.

I looked at photos and read accounts of steam ship and carriage travel, and Melbourne places, faces and vaudevillians from 1888 to 1910. My nephew George was dispatched to the State Library of WA to find the original brochure advertising the auction of land called the Ada Delroy estate; that’s how we found out Jimbell St in Perth, which still survives, is named after Ada’s husband, Jim Bell.

I was lucky enough to jump a discount flight to New York with 12 hours to spare so I could watch a performance by choreographer and dancer Jody Sperling, who interprets the dances of Loïe Fuller, wearing re-created and constructed Serpentine costumes. I was able to speak with her about how Ada might have felt performing those original dances in the costume made from 100 yards of silk. Later, I visited the dressing room under the Theatre Royal in Hobart where Ada once changed into that costume.

I convinced a shopkeeper at the Block Arcade in Melbourne to let me down into the catacombs underneath to explore, so I could set a scene there. I didn’t want to stop researching, but with a head full of images and facts and ideas, after two years of research, it was time to write.

I didn’t use every photo or reference everything I’d read or investigated, but it all combined to help me imagine my way into Ada’s life and give her a voice. I hope I’ve done her proud.