Preprint

Article

Variability of Lightning and Precipitation Associated with Lightning-Caused Wildfires in the Central and Eastern United States

Altmetrics

Downloads

109

Views

36

Comments

0

A peer-reviewed article of this preprint also exists.

This version is not peer-reviewed

Submitted:

22 May 2023

Posted:

23 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Alerts

Abstract

The horizontal storm structure surrounding lightning ignited wildfires is examined using Vaisala’s National Lightning Detection Network (NLDN), NCEP’s Stage IV gauge corrected radar precipitation mosaic, and the US Forest Service’s Fire Occurrence Database. Though lightning flash density peaks strongly around fire ignitions on the instantaneous 1 km scale, on the hourly 10 km scale both the lightning and precipitation peaks are typically offset from fire ignitions. Lightning density is higher and precipitation lower around ignition points compared to non-ignition points. Both regression and horizontal distributions are consistent with the claim that positive flashes have a stronger association with ignition than negative flashes, but the statistical significance remains ambiguous

Keywords:

Subject: Environmental and Earth Sciences - Atmospheric Science and Meteorology

1. Introduction

In the last two decades lightning has been responsible for roughly 14% of reported forest fire ignitions in the United States (Schultz [1] as extracted from the dataset of Short [2]). In contrast to the more common human-caused ignitions, lightning ignitions are nearly equally likely to occur in sparsely inhabited areas where the response time is often slower or nonexistent, so that the total acreage burned by lightning ignition outweighs that due to human causes [3,4]. Most such ignitions are attributed to “dry lightning”; i.e., lightning flashes in the presence of little or no rain [4,5,6]. Our previous work [7] demonstrated that for data binned on regional and annual scales the correlation between dry lightning and wildfire ignitions can be increased by including a regionally adjustable dry period before each candidate flash. The current work examines storm structure associated with lightning ignition at the km and hourly scale.

Previous authors have examined dry lightning primarily in the context of larger scale atmospheric patterns such as a dry layer below the convectively active layer, finding an increase in ignitions per flash for such conditions [6]. Modeling that accounts for large scale transport affecting moisture and stability has shown skill in predicting wildfire breakouts [4,5,8]. An alternate way for dry lightning to occur is horizontal displacement of flashes from the precipitation associated with it, which will be examined to some extent in this work.

Flash ignition is also dependent on the current magnitude and duration, and it is commonly assumed that a long continuing current (LCC) is necessary for ignition [9]. Positive flashes are four times more likely to have an LCC than negative flashes [10,11] so should be more likely to cause ignitions, yet the literature shows mixed results. For example, Anderson [9] modeled wildfire ignitions based on the assumption that only LCC would ignite fires, and found correlation coefficients ranging from 0.3 to 0.76, though other complicating variables such as rainfall, moisture content and survival time were modeled rather than observed. Nausler [12] found a significant increase in the ratio of positive to negative strikes in the vicinity of fire ignitions, though cautioned that the greater tendency of positive strikes to land outside the precipitation core could contribute to the relationship. Schultz et al [1] found that 90% of the lightning flashes closest to ignition points were negative: mirroring the ratio of all negative to positive flashes and thus indicating ignition is independent of LCC, agreeing with Flanagan and Wooten [13].

A recent study most closely aligned to that presented here is the 2020 work of MacNamara et al [14], which examined the fine resolution statistics of lightning and rainfall in the vicinity of lightning ignited fires. They found that fire ignitions, spatial lightning and rain peaks were rarely co-located, with lower rain rates and slightly higher flash densities found in the immediate vicinity of ignition points. Positive flashes were no more likely to cause ignitions than negative flashes. Though our work uses a different fire dataset and a coarser precipitation dataset over a different time and space domain, it is important to recognize that we independently confirm nearly all their qualitative results and are in reasonable agreement with their numerical results. The main analytical extension in this work is the comparison of the characteristics of storms that are and are not associated with fire ignitions, while the previous work compared lighting and rain that is immediately adjacent to ignitions to that which is nearby.

This work is focused on surface lightning strikes and the horizontal structure of storms surrounding such strikes. We employ the ability of lightning detection based on radio time-of-arrival and triangulation [15] to single out flashes that strike the ground, and a gauge-adjusted radar precipitation product for a gridded estimate of the amount of precipitation that reaches the ground [16]. Satellite and weather model analysis may be incorporated later to get a fuller view of storm structure. This work will focus on atmospheric phenomena only rather than the equally crucial fuel condition [17,18], which will be treated as random background noise; an approach which is only feasible when hundreds of observations can be averaged together for each point displayed.

Following a description of the datasets the temporal and horizontal distributions of lightning around ignition points is examined on the km scale. Precipitation is introduced and its horizontal distribution relative to lightning is explored on the scale of tens of km. After a statistical assessment of the effects of positive versus negative flashes on lightning ignition, the paper concludes with a comparison of the characteristics of storms that are and are not associated with fire ignitions.

2. Data Sets and Collation into Ignition Events

This study is built around a fire ignition dataset with associated lightning and rain. The dataset includes CONUS data east of 114 W longitude and from years 2003 to 2015 to avoid irregularities in the precipitation and lighting databases as discussed below.

2.1. Fire Occurrence Database

The fire database is extracted from the US Forest Service’s Fire Program Analysis Fire Occurrence Database (FPA-FOD) produced from the National Fire Incident Reporting system [2]. It includes reporting from federal, state, and local agencies; and as reporting is voluntary the database is best described as extensive rather than comprehensive. Reporting times are recorded without attempt to estimate the ignition time, which is taken to be typically within the same day as the reporting time. Though the ignition point of fires on federal lands would be estimated by ground survey, the majority of fires in this dataset are east of the Rocky Mountains, so are primarily on private land. The locations of fires in these cases are given by the street address of the property, unlikely to align closely with the fire locations on large properties. Only those fires reported as caused by lightning are used for this analysis. By associating this dataset to lightning strikes (as is done in this work) Schultz et al [1] found that 95% of fire ignitions were within ~5 km of the stated location. Roughly half could not be associated with lightning on the same day, attributed to smoldering before breaking out into full fire.

2.2. National Lightning Detection Network

Lightning data are derived from Vaisala’s National Lightning Detection Network (NLDN), which consists of a network of about 200 VLF/LF radio frequency receivers over CONUS that combine time-of-arrival and triangulation technologies to locate the location of lightning flashes to an accuracy of 0.5 km [13,19,20]. Peak current of the first return stroke and the multiplicity (i.e., the number of strokes per flash) are available in the dataset. Best accuracy is achieved for flashes with currents exceeding 15 kA [20,21] but this restriction is only applied for the gridded data described below. A significant upgrade to the NLDN occurred in 2002-2003, which motivated us to restrict our analyses to NLDN data from 2003 and later.

2.3. Stage IV Precipitation Radar Data

Precipitation data is taken from NCEP’s Stage IV blended radar/gauge gridded mosaic. The hourly accumulated NexRad radar data is calibrated to accumulated gauge data at 4 km resolution by the regional River Forecast centers [16]. From 2004 until 2015 many of the regional centers would not certify results over much of the Rocky Mountains, and so our work is restricted to east of 114 W longitude (Figure 1). The original mosaic is on an area preserving grid that does not align with the lat/lon grid, so for ease of comparison to other data sets was rebinned to a 0.1-degree square grid.

2.4. Collating Data to Ignition Events

Each fire ignition was associated to all flashes within a 0.1-degree box centered on the ignition point that fell within +/- 2 days of the reported fire. Distances between flashes and the reported ignition point were calculated, as were area-weighted averages of flash rate and current in radius bins of 1 km up to 5 km. For each flash the time to a preceding rainfall of 0.1, 0.2 and 0.5 mm/hr were tabulated up to a maximum of 7 days (a procedure similar to Vant-Hull et al [7]).

To include the coarser precipitation data the procedure pivots to an examination of overall storm pattern in the vicinity of fire ignitions. Fire, lightning and precipitation data were binned into 5x5 grids at 0.1-degree resolution centered on each fire ignition point. A separate analysis was performed similar to the above but for which spatial lightning density maxima were used as grid centers so that fire and non-fire cases could be compared. A lightning peak was classified as “fire” if an ignition occurred at any point in the 5x5 grid within +/- 1 day.

All the gridded analysis with related figures were performed by the following procedure:

- A fixed grid of 0.1 x 0.1 degrees is imposed on CONUS, with data within each spatial bin accumulated over each hour.

- Points of interest are detected, defined either by a) fire ignitions or b) spatial lightning maxima within this grid system.

- 5x5 grids are retained centered on each of these points of interest, used to form the spatial average environment around either a) fire ignitions or b) lightning maxima.

Since the ignition data is only available at daily resolution, all occurrences of lightning and rainfall within +/- 24 hours of noon on the day of an ignition are associated with it. Lightning maxima are classified and averaged separately depending on whether a fire ignition is present within the 5x5 grid surrounding it. Since fires tend to cluster this procedure of recentering on each ignition point means that many features will be counted several times. But as we are interested in defining average local environments, this repeat counting is not a distortion.

For the gridded data, lightning is restricted to currents greater than 15 kA and precipitation greater than 0.5 mm/hr. In the interest of space the gridded analysis is not broken down by region.

In many cases the average pattern is very different from most individual patterns. Since individual cases are of primary interest, statistics of the location of fires and rain peaks relative to spatial lightning peaks are compiled.

The data is filtered by Julian day: retaining only those from mid May through mid September, reducing the proportion of frontal storms as well as frozen precipitation. The fine scale analysis is subdivided into regions corresponding to the national Forest Service divisions, as shown in Figure 1. The use of rectangular areas greatly speeds the calculations without a large impact on regional differences. The colors shown are used throughout the analysis to represent various regions, with the entire area denoted by black. The coarse scale analysis is CONUS wide.

3. Results and Analysis

3.2. Flash Density versus days from Ignition.

The frequency of lightning flashes as a function of days relative to the stated day of ignition appears in Figure 2. The normalized compilation of all flashes exhibits a very similar peaked pattern among all the regions except the southeast, which is skewed towards flash densities prior to the stated ignition day. Typically 90% of flashes that occur do so within +/- 1 day of the fire ignition, so the analysis is limited to +/- 2 days (note that for roughly 50% of fires not attributed to human causes there are no associated flashes in this time range, hence the attribution to smoldering lightning ignitions referred to in the introduction). Storms may occur multiple times during this 5-day period, so to assess the accuracy of the storm ignition data it’s best to look at periods with only one storm. This is done on the right side of Figure 2, still weighted by the total number of flashes. This indicates that the Northern Rockies are most likely to have one storm during a 5-day period, while the South-East region is highly likely to have multiple storms, dropping to the lowest percentage of flashes. All patterns remain peaked, though less so in the southern regions. The SE outlier curve on the left is attributed to the Florida peninsula, host to the highest flash density in CONUS [21]. This makes it less likely to have lone storms in a 5-day period, so the SE fraction is greatly reduced on the right. The magnitudes of other regions behave in a similar manner.

3.2. Flash Density versus distance from Ignition.

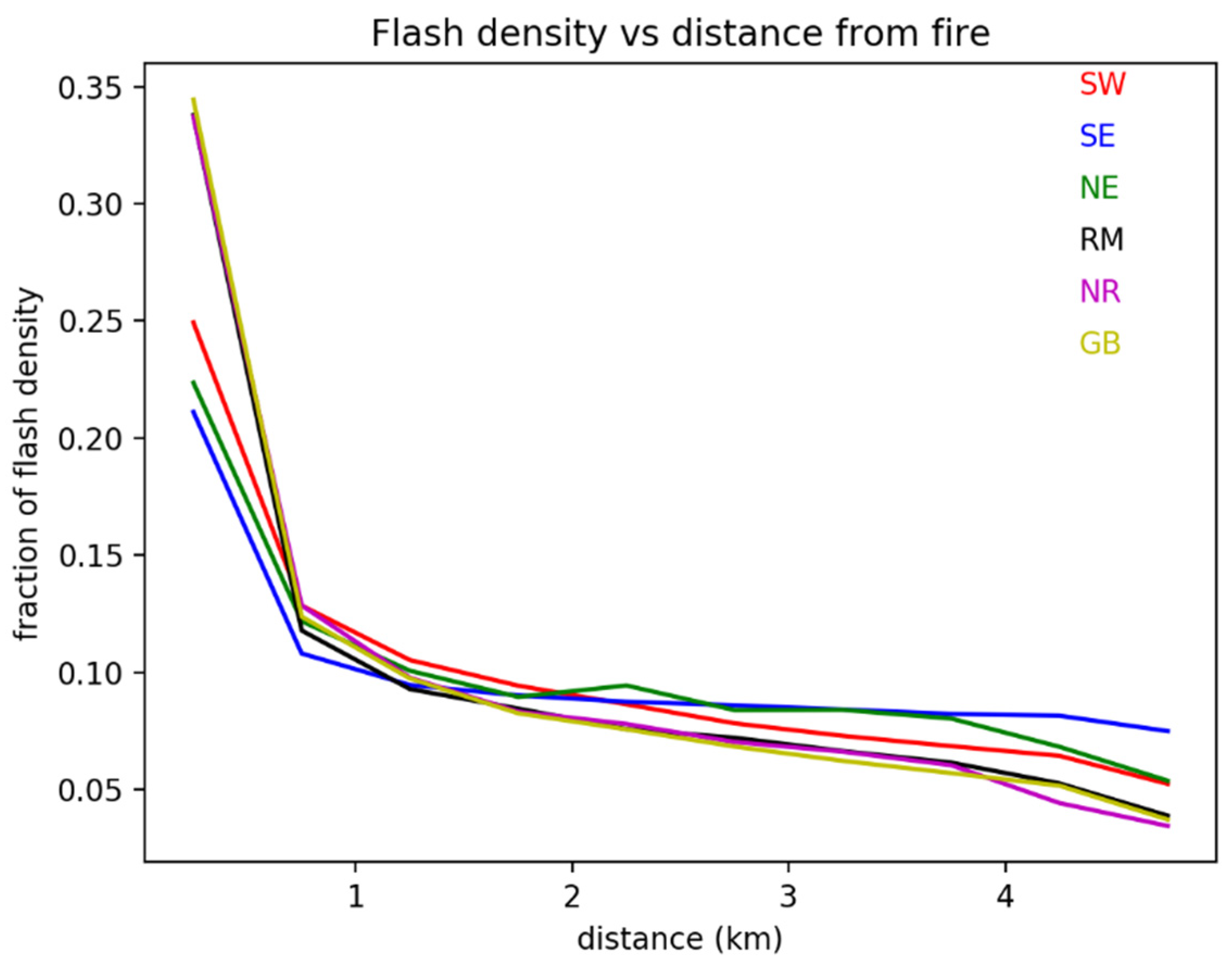

Flash density and total current are shown as a function of distance on the top row of Figure 3, with regional differences shown in color. The densities are greatest in the vicinity of the fire, falling off immediately (in the first km) to low density with a slow decline with distance, resembling the results of MacNamara et al [14]. The Great Basin and Northern Rocky regions have the most pronounced peak, consistent with the temporal peaks of Figure 2, as densities in space and time are related.

3.3. Flash Current

Figure 4 examines lightning current in the vicinity of fire ignitions. The normalized shape of the current histogram (4a) remains unchanged with region: shifted towards negative current, with a smooth transition into positive current. If the negative flashes are separated out (4c) their average current with distance from the fire location decreases slightly with distance [14], and the averages vary up to 20% with region, with the Southeast currents the largest. The fraction of total current that is positive doesn’t show a clear pattern with distance from the fire (4d), though there are clear regional differences with the Southeast having the smallest fraction of positive current. A drop in positive current with distance from a fire ignition (bottom right) is only clear in the Northeast and Southeast. The fraction of positive flashes roughly mirrors the current amplitude of these flashes (4b). It should be noted that the South-East region has much higher negative current and much lower positive current than the other regions, reflecting the same anomalous behavior seen in Figure 2.

3.4. Spatial Patterns of Precipitation and Lightning

For comparison to precipitation the 5x5 grids at 0.1 degree resolution are formed for averages of precipitation, flash count, maximum current (positive and negative) and positive flash fraction. These grid averages appear in Figure 5, showing these values accumulated in the vicinity of each fire ignition (refer to section 2 for a description of how these are formed). The flash rate and current peak at the fire ignition points in the center, while the precipitation peak is offset to the northeast. Though both flash rate and precipitation tend to peak in the convective core of storms, the precipitation continues for a longer period [22], so over the hourly average will become displaced in the prevailing direction of travel. The positive flash count is less strongly peaked than the total flash count because positive flashes are more likely to originate in the anvil rather than the core [24].

Positive flashes are rarer than negative flashes but tend to have longer lasting current flows, so are assumed to be more likely to ignite fires [10,11]. In figure 6 the ignitions per flash in the vicinity of each ignition is shown. If all ignitions that occurred per each hour period were spaced more than 0.3 degrees apart the fire density on the left of Figure 6 would be a single spike at the center, as would be the ignitions per positive or negative flashes. Given that fires and flashes cluster around an ignition point, it is rather surprising that the ignitions per negative flash actually are lower at the point of ignition, while the ignition ratio for positive flashes is higher at the center as expected. There are several possible reasons for this. Our approach examines each fire in turn, so that the ignition probability for the central fire is a binary variable always equal to 1 while the total flash rate is strongly peaked at the ignition location. This explains the drop in ignition ratio in total lightning as an artifact of the selection process. But to explain why a similar drop is not seen in the positive flash count will require a deeper examination of the storm structure.

3.5. Lack in Spatial Coincidence of Ignitions, Lightning and Precipitation Peaks

The strong central tendency of total flash density should not be confused with the density of peak locations during individual events. When peak locations alone are examined, the density of lightning peaks is slightly peaked at ~8% above the average at the fire location (graphics not shown due to low contrast), even though the total flash density is strongly peaked over the fire location (Figure 5). This means that for a majority of events the lightning peak does not coincide with the point of ignition (compare to MacNamara et al, [14]). An analogy would be overlapping Gaussian distributions for which the central peak of the total distribution does not correspond to individual peaks. The rain and lightning peaks are strongly coincident, despite the total rainfall being shifted weakly to the NE (Figure 5).

Individual ignition events can be examined for the occurrence of local peaks in lightning flash density and precipitation, as well as the presence or absence of precipitation or lightning. These statistics appear in Table 1. We see immediately that the most common scenario is no rain or lightning, and the possibility of not having a lightning flash coincident within the same day of ignition is 72.4%. Schultz et al [1] observed a 50-60% lack of coincidence of lightning within a 5 km radius, which they attributed to smoldering before the fire became evident enough to be reported. A possible reason for the discrepancy is the restriction to data largely east of the Rockies in the current work, which means lower reporting rates of small fires in the less inhabited mountains are discounted.

If the row of Table 1 relating to the no lightning cases is ignored, we see that it is roughly 2.5 times more likely for ignitions to occur if they are not coincident with a local peak in lightning; perhaps because the rainfall is typically higher at the lightning peaks. This helps explain the drop in ignition efficiency for total flashes near the ignition points; in fact it’s 5 times more likely for fires to be ignited when offset from the rain peak. But the positive lightning flash density is less strongly peaked: due to the tripole charge structure of storms, positive flashes are more likely to occur in the anvils and stratus shield than negative flashes - which concentrate more in the precipitation core [24,25,26]. The ratio of negative charges to positive is therefore much larger in the core, and so even though the ignitions per flash are suppressed due to rain, the number of ignitions is higher. The result is a false sense that the positive flashes are more efficient in producing ignitions in the center, when instead the increase in negative flashes is responsible for the increase in ignitions.

3.5. Regression of Flash Density versus Ignition Density

The other reason why the positive ignition ratio more closely matches the ignition pattern compared to negative flashes is the longer continuing current, which makes positive flashes more efficient at ignition, and therefore more closely correlated to ignitions. This can be shown by multivariable regression relating positive and negative flash densities of Figure 6 to ignition density (Figure 7). The plot of all ignitions vs all flashes provides a strong correlation but has a non-zero intercept.

When the flashes are split into positive and negative, it is seen that each positive flash is roughly 60 times more likely to ignite a fire than a negative flash, and the intercept is nearly cut in half at the sacrifice of a slightly lower correlation. The sum of absolute deviations is also about 5% smaller when positive flashes are included in the model, tipping the balance towards the combined model. These positive indicators combined with the drop in adjusted correlation means model improvement due to the introduction of polarity remains ambiguous.

It should be emphasized that this linear fit to 25 grid points applies to the results of summing over a large number of cases in which ignition occurred in the immediate vicinity, preconditioning regional fuel state while averaging out local variability. If the fitting was done to individual flashes the effects of vegetation would be more apparent and the correlations would be much lower.

The fit would be improved if the point at the top right was slightly higher in the observations. This point corresponds to the central ignition point at which average rainfall increases, which dampens ignition efficiency and is not accounted for in the model. Though removal drops the overall ignition rate ratio of positive:negative flashes down to roughly 50:1, the change in the quality of fit when the polarity is introduced remains as ambiguous as before, so is not reported.

The more physically reasonable model of relating ignition density to the combined (flash density) x (average current) was slightly less successful, perhaps because ignitions are more likely caused by extreme flashes, and current averaged over 10x10 km squares does not well represent the distribution of individual flashes. A model that included rainfall was also less successful, presumably for the same built-in assumption of gridpoint-wide uniformity of rainfall.

3.6. Comparison of Lightning Density Peaks: fire versus no fire

All the analysis so far has looked at the conditional statistics in the presence of a wildfire ignition. It would be illuminating to compare ignition events to non-ignition events, but then we require an independent definition of an event. A good candidate is the location of flash density peaks, so that the properties of lightning peaks with and without co-located fire ignitions can be compared. A spatial comparison appears in Figure 8, for which each row of fire versus no fire is normalized to the maximum value of that row. A lightning peak was classified as “no fire” if there were no ignitions in the 5x5 grid centered on the peak.

Several of the behaviors in Figure 8 are expected: the average flash density is higher and the precipitation is lower in the presence of fire ignitions. Though the trend is slight the precipitation does reach a peak coincident with the flash peak if there is no fire, but this shallow peak is translated to the NE if fire is present. The average positive flash rate and average current is also higher during ignition events, though the weighting of positive flashes to the south while precipitation is weighted to the north (as expected due to storm motion) remains unexplained. The roughly 50% increase of the peak value of positive flash counts from the no-fire to the fire cases matches that of the overall lightning count, though the positive lightning counts exhibit less contrast from rim to center peak.

4. Discussion: applicability and future work

The most unique aspect of this work is the demonstration that the fire ignitions are more likely to occur when the rainfall peak is spatially offset from the lightning peak. Can this be applied to fire forecasting systems such as the widely used Wildland Fire Assessment System (WFAS) [27,28,29,30] that estimates wildfire occurrence based on weather predictions and fuel moisture? Spatial offsets between precipitation and lightning could occur because surface rainfall is affected by the horizontal wind field more than lightning. Upper-level wind forecasts are readily available, though in most cases lightning would be striking moistened fuel. Alternatively, differences in timing of peak occurrence combined with storm motion would also result in horizontal displacement of lightning and precipitation. Since predictions would need to include detailed storm modelling this second mechanism is less applicable to large scale forecasting. Both these mechanisms would be most relevant in the absence of a dry layer below the storm clouds that evaporates precipitation before hitting the ground [6].

The location of ignitions relative to lightning peaks and storm motion vector would help establish if lightning striking outside the storm would remain dry due to storm path. This aspect may be important though difficult to predict; and will be included in the next stage of work.

The National Lightning Detection Network used in this work detects ground strikes but cannot capture continuing current. The GOES 16 Lightning Mapper (GLM) has complementary capabilities, so a merge of the two instruments would be a large step forward in lightning ignition studies. A continuation of this work comparing long continuing current ground strikes to shorter current strikes will be pursued.

5. Conclusions

On the fine scale lightning flash density drops quickly with distance from an ignition, by a factor of between 2 and 3 within the first km distance before flattening out. Current and positive flash fraction drop more gently with distance, exhibiting a much greater variation with region that does total flash count. We saw that roughly 70% of reported fires could not be associated with lightning on the same day, an effect Schultz et al [1] attributed to smoldering with a similar miss rate of 50-60%.

Moving to the coarser scale 0.1-degree grids, we see that in the presence of fire ignitions total lightning is more sharply peaked than either positive flash count or current, while average rainfall is offset to the NE. The ratio of ignitions per flash for total lightning is actually lower at the fire ignition location, due to strongly peaked lightning density. For positive flashes the ignitions per flash ratio is higher at ignition points. However, individual cases show a different pattern from the average patterns: it is unlikely for fire ignitions, lightning peaks and precipitation peaks to all coincide, being just one of several possible configurations. This agrees with recent results by other researchers [14].

Multivariable linear regression suggests that positive flashes are roughly 60 times more efficient at igniting fires than negative flashes. The positive flash density tends to peak more strongly during ignition events. Though this result is consistent with the assumption that positive flashes are more efficient at fire ignition, we can not claim the case to be statistically definitive, and it is not supported by the flash density ratios in this work or other recent studies [1,14].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.V. and W.K..; methodology, B.V..; software, B.V.; validation, B.V..; formal analysis, B.V..; investigation, B.V.; resources, W.K..; data curation, B.V..; writing—original draft preparation, B.V..; writing—review and editing, W.K..; visualization, B.V.; supervision, W.K..; project administration, W.K..; funding acquisition, W.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Precipitation and Lightning Work Package for the Internal Science Funding Model (ISFM) project Lightning as an Indicator of Climate under NASA Headquarters (Dr. Jack Kaye and Dr. Lucia Tsaoussi), that supports NASA's participation in the National Climate Assessment (NCA).

Data Availability Statement

The Wildfire Occurrence Database is freely available from https://www.fs.usda.gov/rds/archive/Product/RDS-2013-0009.5. Stage IV gridded and gauge corrected precipitation radar data is freely available from http://data.eol.ucar.edu/dataset/21.093. The Vaisala Lightning Detection Network archived data is available by request or real-time data available for purchase from https://www.vaisala.com/en/products/national-lightning-detection-network-nldn.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Vaisala Inc. for providing the NLDN data used in this study, as part of the Marshall Mentored Project (MMP, ID #02). We also acknowledge the Stage 4 radar data provided by NCAR/EOL under sponsorship of the National Science Foundation. The authors gratefully acknowledge the guidance of Karen Short of the U.S. Forest service in the use of the Wildfire Occurrence Database.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Schultz, C., N. Nausler, J. B. Wacher, C. R. Hain, J. R. Bell. Spatial, Temporal, and Electrical Characteristics of Lightning in Reported Lightning-initiated Wildfire Events. Fire, 2019, 2(18). [CrossRef]

- Short, Karen C. Spatial wildfire occurrence data for the United States, 1992-2015 [FPA_FOD_20170508]. 4th Edition. Fort Collins, CO: Forest Service Research Data Archive. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Balch, J.K.; Bradley, B.A.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Nagy, R.C.; Fusco, E.J.; Mahood, A.L. Human-started wildfires expand the fire niche across the United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 2017, 114, 1946–2951.

- Nauslar, N. J., M. L. Kaplan, J. Wallmann, and T. J. Brown., A forecast procedure for dry thunderstorms. Journal of Operational Meteorology, 2013, 1(17), 200-214.

- Rorig, M., S.J. McKay, S.A. Ferguson, Model generated predictions of dry thunderstorm potential. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology, 2007, 46, 605-614.

- Rorig, M. and S. Ferguson. characteristics of lightning and wildland fire ignition in the Pacific Northwest. Journal of Applied Meteorology,1999, 38, 1565-1575.

- Vant-Hull, B., Thompson, T., & Koshak, W. Optimizing precipitation thresholds for best correlation between dry lightning and wildfires. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. 2018, 123, 2628-2639. [CrossRef]

- Wallmann, J., R. Milne, C. Smallcomb, M. Mehle. Using the 21 June 2008 California Lightning Outbreak to Improve Dry Lightning Forecast Procedures. Weather and Forecasting, 2010 25(5), 1447-1462.

- Anderson, K., (2002), A model to predict lightning caused fire occurrences. International Journal of Wildland Fire. 11, 163-72. [http://www.cfs.nrcan.gc.ca/bookstore_pdfs/19949.pdf].

- Uman, M. A. The Lightning Discharge. International Geophysics Series, 1987, 39, 377 pp.

- Rakov, V. and M. Uman, The Lightning Flash, ISBN 0 521 58327 6, Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Nauslar, N.J. Examining the Lightning Polarity of Lightning Caused Wildfires. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Lightning Detection Conference, Tucson, AZ, USA, 18–19 March 2014.

- Flannigan, M. D. and B. M. Wotton, (1991), Lightning ignited forest fires in northwestern Ontario. Canadian Journal of Forestry Research, 21, 277-87.

- MacNamara, Brittany, Christopher Schultz, Henry Fuelberg. Flash Characteristics and Precipitation Metrics of Western U.S. Lightning-Initiated Wildfires from 2017. Fire, 2020, 3,4. [CrossRef]

- Cummins, K. L., and M. J. Murphy. An overview of lightning locating systems: History, techniques, and data uses, with an in-depth look at the US NLDN. IEEE Transactions Electromagnetic Compatability, 2009, 51, 499–518.

- Lin, Ying and Kenneth Mitchell. The NCEP stage II/IV hourly precipitation analysis: development and applications. 19th Conference on Hydrology, American Meteorological Society, 2005, Paper 1.2. [https://ams.confex.com/ams/Annual2005/webprogram/Paper83847.html].

- Wooten, B. and D. L. Martell. A lightning fire occurrence model for Ontario. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 2005, 35, 1390-1401.

- Rollins, M. G., (2009), LANDFIRE: a nationally consistent vegetation, wildland fire, and fuel assessment. Journal of Wildland Fire, 18, 235-249.

- Biagi, C. J., K. L. Cummins, K. E. Kehoe, and E. P. Krider. National Lightning Detection Network (NLDN) performance in southern Arizona, Texas, and Oklahoma in 2003–2004. Journal of Geophysical Research, 2007, 112, D05 208. [CrossRef]

- Orville, R.E., G.R. Huffines, W.R. Burrows, K.L. Cummins. The North American Lightning Detection Network (NALDN) – Analysis of Flash Data, 2001-09. Monthly Weather Review,2011, 139, 1305-1322.

- Bourscheidt, V., K.L. Cummins, O. Pinto, K.P. Naccarato. Methods to Overcome Lightning Location System Performance Limitations on Spatial and Temporal Analysis: Brazilian Case, Journal of Oceanic Technology-A, 2012, 29, 1304-1311.

- Koshak, W. J., K. L. Cummins, D. E. Buechler, B. Vant-Hull, R. J. Blakeslee, E. R. Williams, and H. S. Peterson. Variability of CONUS lightning in 2003–12 and associated impacts. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology, 2015, 54, 15-41.

- Rigo, T., N. Pineda, J. Bech. Analysis of warm season thunderstorms using an object-oriented tracking method based on radar and total lightning data. Natural Hazards Earth Systems Science. 2010, 10, 1881-1993.

- Rutledge, S. A., C. Lu, and D. R. MacGorman. Positive cloud-to ground lightning in mesoscale convective systems, J. Atmos. Sci., 1990, 47, 2,085–2,100.

- Saunders, C.P.R. A review of thunderstorm electrifications processes. J. Appl. Meteor., 1993, 32, 642- 655.

- Nag, A. and V. Rakov. Positive lightning: an overview, new observations and inferences. Journal of Geophysical Research, 2012, 117, D08109. [CrossRef]

- Sopko, Paul; Latham, Don; Grenfell, Isaac. Verification of the WFAS Lightning Efficiency Map In: Butler, Bret W.; Cook, Wayne, comps. The fire environment--innovations, management, and policy; conference proceedings. 26-30 March 2007; Destin, FL.

- Sopko, Paul; Bradshaw, Larry; Jolly, Matt. Spatial Products available for identifying likely wildfire ignitions using lightning location data-Wildland Fire Assessment System (WFAS). In Proceedings of the 6th International Lightning Meteorology Conference, San Diego, CA, USA 18-21 April 2016.

- Burgan, R. E., Andrews, P. L., Bradshaw, L. S., Chase, C. H., Hartford, R. A., & Latham, D. J. Current status of the Wildland Fire Assessment System (WFAS). Fire Management Notes,1997, 57, 18–21.

- Bradshaw, L. S., Deeming, J. E., Burgan, R. E., & Cohen, J. D. The 1978 national fire-danger rating system: Technical documentation. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service General Technical Report INT-169, 1983. [https://www.fs.usda.gov/treesearch/pubs/29615].

Figure 1.

National Inter Agency Coordination regions (a), with rectangular approximations (b). The two letter initials shown in (b) will be used throughout this report. Figure (a) adopted from the National Interagency Coordination Center Wildland Fire Summary and Statistics Annual Report, 2003.

Figure 1.

National Inter Agency Coordination regions (a), with rectangular approximations (b). The two letter initials shown in (b) will be used throughout this report. Figure (a) adopted from the National Interagency Coordination Center Wildland Fire Summary and Statistics Annual Report, 2003.

Figure 2.

Temporal distribution of lightning flashes relative to reported day of fire ignition. (a): Distributions for the case of any number of storms during the 5-day period. (b): Distributions for the case of only one storm during the 5-day period. (b) is weighted by the same total flashes as (a).

Figure 2.

Temporal distribution of lightning flashes relative to reported day of fire ignition. (a): Distributions for the case of any number of storms during the 5-day period. (b): Distributions for the case of only one storm during the 5-day period. (b) is weighted by the same total flashes as (a).

Figure 3.

Flash density as a function of distance from fire ignitions, normalized by region. Colors correspond to the regions of Figure 1.

Figure 3.

Flash density as a function of distance from fire ignitions, normalized by region. Colors correspond to the regions of Figure 1.

Figure 4.

Flash current characteristics. (a): Normalized distribution of flash currents, by region. (b): Fraction of total current that is positive as a function of distance from fire ignition, separated by region. (c): current of negative flashes as a function of distance from fire ignition, separated by regions. (d): current of positive flashes as a function of distance from ignition, separated by region.

Figure 4.

Flash current characteristics. (a): Normalized distribution of flash currents, by region. (b): Fraction of total current that is positive as a function of distance from fire ignition, separated by region. (c): current of negative flashes as a function of distance from fire ignition, separated by regions. (d): current of positive flashes as a function of distance from ignition, separated by region.

Figure 5.

Lightning and precipitation in the vicinity of wildfire ignitions. The images represent the averages of values in a 5x5 grid, each bin 0.1 degree on a side. The fire ignition is located in the central point. All plots are normalized to their maximum.

Figure 5.

Lightning and precipitation in the vicinity of wildfire ignitions. The images represent the averages of values in a 5x5 grid, each bin 0.1 degree on a side. The fire ignition is located in the central point. All plots are normalized to their maximum.

Figure 6.

Comparing ignitions per flash for negative (middle) or positive (right) polarity. These are averages centered on each wildfire ignition. For context the average ignition density is presented (left). All diagrams are normalized to their maximum.

Figure 6.

Comparing ignitions per flash for negative (middle) or positive (right) polarity. These are averages centered on each wildfire ignition. For context the average ignition density is presented (left). All diagrams are normalized to their maximum.

Figure 7.

Plots of ignition density vs flash density summed over each 5x5 0.1-degree grid centered on each ignition Left: plot of ignitions vs ALL flashes. Right: Plot of observed ignitions vs predicted ignitions from multivariable liner regression model based on positive and negative flash density. The R squared values are adjusted to account for the number of predictor variables.

Figure 7.

Plots of ignition density vs flash density summed over each 5x5 0.1-degree grid centered on each ignition Left: plot of ignitions vs ALL flashes. Right: Plot of observed ignitions vs predicted ignitions from multivariable liner regression model based on positive and negative flash density. The R squared values are adjusted to account for the number of predictor variables.

Figure 8.

Spatial patterns centered on lightning peaks not associated with ignitions (left) versus peaks with fires (right). Normalization is relative to the highest value of each row.

Figure 8.

Spatial patterns centered on lightning peaks not associated with ignitions (left) versus peaks with fires (right). Normalization is relative to the highest value of each row.

Table 1.

Occurrence of precipitation, lightning flashes and their peaks in the vicinity of reported wildfire ignitions.

Table 1.

Occurrence of precipitation, lightning flashes and their peaks in the vicinity of reported wildfire ignitions.

| % | No Rain | Rain Present | Rain Peak | row totals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Lightning | 61.1 | 10.0 | 1.3 | 72.4 |

| Lightning Present | 3.4 | 14.6 | 1.7 | 19.7 |

| Lightning Peak | 1.4 | 5.4 | 1.1 | 7.9 |

| Column totals | 65.9 | 30.0 | 4.1 | 100% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Copyright: This open access article is published under a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license, which permit the free download, distribution, and reuse, provided that the author and preprint are cited in any reuse.

Variability of Lightning and Precipitation Associated with Lightning-Caused Wildfires in the Central and Eastern United States

Brian Vant-Hull

et al.

,

2023

Probabilistic Forecasting of Lightning Strikes over Continental US and Alaska: Model Development and Verification

Ned Nikolov

et al.

,

2024

The 2017 North Bay and Southern California Fires: A Case Study

Nicholas J. Nauslar

et al.

,

2018

MDPI Initiatives

Important Links

© 2024 MDPI (Basel, Switzerland) unless otherwise stated