Preprint

Article

Dietary Intake With Supplementation of Vitamin D, Vitamin B6, and Magnesium on Depressive Symptoms: A Public Health Perspective

Altmetrics

Downloads

121

Views

59

Comments

0

A peer-reviewed article of this preprint also exists.

This version is not peer-reviewed

Submitted:

09 June 2023

Posted:

12 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Alerts

Abstract

Background: Studies addressing diet quality and mental health have shown a strong association. There is limited evidence of specific vitamins essential for treating depression. This study aims to understand the impact of diet quality through supplementation of vitamins D, B6, and magnesium on depressive symptoms. Methods: Multiple datasets from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017-March 2020 investigated the associations between vitamin D, B6, and magnesium on depression symptoms. A cross-sectional sample of adults over 20 was extracted (n=9,232). Chi-square tests and logistic regression analyses were used to investigate the associations. Results: Individuals with low doses of vitamin D were more likely to report symptoms of depression relative to those with low doses of vitamin B6 (χ²=3.9063, p=0.0481 vs. χ²=5.2071, p=0.0225). These results remained significant among those with high magnesium proportionate to high vitamin B6 (χ²=6.1272, p=0.0133 vs. χ²=5.2071, p=0.0225). Logistic regression results provided associations for all models except unadjusted vitamin D and adjusted vitamin D. Conclusions: Preventive measures could be addressed by identifying the risks of vitamin deficiencies. Further epidemiological research is needed for the individual effects of vitamin supplementation and depression symptoms.

Keywords:

Subject: Public Health and Healthcare - Other

1. Introduction

Nutrition is “the process of consuming, absorbing, and using nutrients from the food that are necessary for growth, development, and maintenance of life” [1]. Nutritional psychiatry uses food and supplements as alternative mental health disorders treatments [2,3]. Most current treatments for mental health disorders focus on treating symptoms. Additionally, food-insecure individuals historically are more at risk for low immune system response and are more susceptible to infection and disease [4]. The prevalence of harmful mental health outcomes in adults is increasing even with the increase of reports of the benefits of micronutrients and food on mental health[5,6].

Depression affects about 350 million people worldwide and, along with other mental health conditions, compromises the main contributor to global disability [7]. Major depressive disorder is a common, chronic condition that imposes a substantial burden of disability globally [7]. Clinical trials, population, and laboratory research prove that healthy dietary patterns such as a Mediterranean-style diet and specific dietary factors, including omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), vitamin B6 and folate, antioxidants, and zinc, may influence the risk for depression [7]. Adherence to traditional dietary habits has been associated with a reduced probability of depression through micronutrients and healthy fats through multiple pathways with optimal brain function. Health benefits are likely related to the combined effects of nutrients on mood. For example, the long-chain omega-3 PUFAs found in fish and antioxidants, such as those found in green tea, may have a role in decreasing the risk of mood disorders and suicide [7]. Promotion of dietary habits that encourage better health and the recognition of individual nutritional components can improve mental health [8,9,10,11,12,13,14].

Therapeutic options for treating mental disorders are developing, and medication and herbal remedies are becoming mainstream [2]. Most current drugs available to treat common psychiatric disorders contain many herbal vitamins and minerals, proven effective by many studies compared to traditional antidepressant medications that are typically prescribed [8]. These nutritional supplements have been shown to improve the clinical outcomes of many patients and are profitable interventions compared to clinical ones. Early life development sets the foundation for the later development of depression symptoms and can influence disease susceptibility [15]. Progress can be made by understanding how these nutrients can affect the important signaling pathways for brain function. The opposite can be seen in studies where unbalanced diets increase the risk of diseases and cognitive decline [15]. Furthermore, improper nutrition and obesity are closely related to regulating mood disorders and stress [2,8,15].

A growing literature has focused on potential risks associated with mental disorders [2,9,15,16,17,18]. A rise in technological improvements, industrialization, and urbanization has helped identify the influences of environmental exposures on genetic variations [16]. More non-communicable chronic diseases have arisen because of modern lifestyle habits. Additionally, the modern era has adopted dietary patterns high in energy-dense foods, refined sugars, trans-fatty acids, unnecessary sodium, limited consumption of plant-based foods, and more caloric intake versus outtake [16]. Due to these reasons, the interest in nutritional psychiatry is growing and strives to understand the relationship between dietary factors and depression conditions [16,19].

The use of dietary supplements to treat depression has previously been researched [7,15,20,21]. However, the full extent of this research has yet to be determined [9]. Treatment of depression primarily targets biological and psychological pathways [20,21,22]. As it is known, the common treatments for depression include antidepressant medication and psychotherapy [7,14,15,20]. Several studies have suggested that lifestyle factors such as diet quality contribute to mental illnesses and play an important role in the risk of depression [2,9,15,16,23]. In particular, a study conducted in Australia aimed to investigate the efficacy of dietary improvement in treating major depression [20]. The results of this study reflected that changing lifestyle factors might contribute to improved outcomes for individuals with major depression and can be a substitute for standard care. A combination of healthy dietary practices may reduce the risk of depression and provide additional benefits for obesity, cardiovascular diseases, and other metabolic syndromes [7].

Depression is associated with increased morbidity and mortality and has many economic and social consequences for an individual. Economic costs as a result of depression has increased the health system's capacity to deal with the surge in mental illness [23]. This issue can lead to stress-related disorders, further mental health damage, and increased economic costs [23]. Given this issue, clinicians and researchers are identifying therapeutic options for depression. Research has been centered on inflammation as a pathophysiological mechanism in depression. Micronutrients are heavily involved in metabolic pathways that impact the development of the functioning of the central nervous system, including brain function. Many micronutrients such as B vitamins, vitamin D, zinc, and magnesium are correlated with decreasing symptoms of depression [8,10,11,12,13,14,17,18,24]. This can explain why there are gaps in the literature related to mechanisms of what a balanced diet with sufficient or insufficient nutritional elements can do for the brain of individuals with depression [14,21,23].

Vitamin D has been at the center of this research, along with vitamin B6 and magnesium. Studies have shown that a lack of these vitamins can be detrimental to one’s health, especially if they are undernourished and lack the consumption of these vitamins and minerals. Many individuals who have depression are reported to have insufficient levels of vitamin D, B6, and magnesium [8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. Intake of a single macronutrient cannot be changed individually as this change in intake of one nutrient can result in a shift in the intake of another. Therefore, examining the relationship between single micronutrient supplementation and health outcomes gives insufficient results because of the dependence on one macronutrient [18].

Many types of vitamins and minerals, such as vitamins D, B6, and magnesium, help with an individual's mental health [10,11,24]. Vitamin D can potentially restore calcium that is needed in the homeostasis of intra- and extra-cellular compartments and other neurotransmitter mechanisms. Research has shown that there is also a possibility that vitamin D controls levels of inflammatory cytokines and systemic inflammation, among others [12]. Several studies found that depressed individuals had lower vitamin D levels than others, and those with the lowest levels had the greatest risk of depression depending on dosage [12,14,25,26].

B vitamins play an integral role in a large number of molecular processes that are essential for the nervous system and brain function, including many that help to maintain an appropriate balance for inhibition [11]. Supplementation with B6 may improve depressive symptoms and has been reported to increase the efficacy of antidepressants or other psychiatric medications [11,24]. High-dose vitamin B6 can be positively associated with the onset of depression and anxiety behaviors and additionally, can influence behavioral outcomes related to inhibition and other stress-related disorders [11].

Magnesium deficiency is common among individuals and produces neuropathologies [10]. Magnesium deficiency does not meet these requirements, which causes neuronal damage and can lead to depression. Consequently, magnesium is recognized in homeopathic medicine for the treatment of depression. Inadequate magnesium intake may be the cause of about 40% of the depression rate in the elderly and about 25% of depression cases in 15-29-year-olds as noted by Eby & Eby (2006). Given this magnesium deficiency can be linked to most mental health-related illnesses such as depression [10].

The primary objective of this study was to fully understand the aspects of diet quality with supplementation of vitamin D, vitamin B6, and magnesium on depressive symptoms in adults aged 20 years and older living in the US.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Questions

The research question for this present study is “Does the intake of vitamin D, vitamin B6, and magnesium impact depressive symptoms in adults aged 20 years and older living in the US?”

H0.

There is no significance between the intake of vitamin D, vitamin B6, and magnesium on symptoms of depression in adults aged 20 years and older living in the US.

HA: There is a significant between the intake of vitamin D, vitamin B6, and magnesium on symptoms of depression in adults aged 20 years and older living in the US.

2.2. Study Design and Subject Recruitment

Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2017-March 2020 database was used to conduct the study [27]. NHANES is “a series of studies to assess the health and nutritional status of adults and children in the United States” [27]. NHANES uses a complex multistage stratified sampling design [27]. Questionnaires were completed using a computer-assisted personal interview system, and laboratory and physical examinations were conducted in Mobile Exam Centers (MEC). The inclusion criteria for this study were those who completed questions related to this topic of study, these responses were gathered from the Dietary Supplement Use 30-Day-Total Dietary Supplements, Mental Health-Depression Screener, and Food Security sections of the dataset and were older than 19 years of age, as 20 was the minimum age that was allowed to be released for marital status. Prior to screening, individuals who reported they were pregnant were excluded to avoid bias toward depression-related pregnancy. Individuals who also reported any chronic diseases were also excluded to remove additional depression-related symptoms from these conditions. Participants who did not answer the nutrition and mental health questions also were excluded from the study. It is important to note that the 2017-March 2020 dataset combines the 2017-2018 and 2019-March 2020 datasets [27].

2.3. Data Collection

A publicly available dataset was used to create a cross-sectional analysis from the NHANES 2017- March 2020 pre-pandemic dataset [28,29,30]. The dataset examines a nationally representative sample of individuals throughout the United States. Data were cleaned to reflect the variables of interest for this study from the following datasets within the database. Data was pulled from the Demographics, Dietary, and Questionnaire Data [28,29,30]. Questionnaire data used the nine-item depression screening instrument for the Mental Health-Depression Screening to determine the frequency of depression symptoms in the two weeks leading up to their physical examination at the MEC [28,29,30,31]. For each question, points ranging from 0 to 3 are assigned to the responses “not at all”, “several days”, “more than half of the days”, and “nearly every day” [30,31]. Additionally, this screening instrument incorporates DSM-IV depression diagnostic criteria [31]. The amount of vitamin B6 in milligrams (mg), vitamin D (D2+D3) in micrograms (mcg), and magnesium in milligrams (mg) are the independent variables that were tested based on the research question. Other demographic variables such as age at screening, gender, race/ethnicity, the highest level of education, marital status, and the ratio of family income to poverty were used as covariates. Household and adult food security variables were also used for analysis as potential confounders for the independent and dependent variables.

The demographic variables listed were recoded to show only individuals 20 years and older per the minimum age to report marital status. SAS provided the values for the variable vitamin D to reflect the median value of the responses. Vitamin D was divided into <17.5 mcg and ≥17.5 mcg to reflect <1.0 as low vitamin D and ≥1.0 as high vitamin D. The values for the variable vitamin B6 were provided by SAS to reflect the median value of the responses. Vitamin B6 was divided into <2 mg and ≥2 to reflect <1.0 as low vitamin B6 and ≥1.0 as high vitamin B6. SAS provided the values for the variable magnesium to reflect the median value of the responses. Magnesium was divided into <50 mg and ≥50 to reflect <1.0 as low magnesium and ≥1.0 as high magnesium. The ten depression screening questions were combined into a depression screening score, with values of 0 or 100. They were recoded as a binary variable as “having depression (100)” or “not having depression (0)”, respectively.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All examinations were completed through SAS software (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Other demographic covariates selected for this study included age, gender, race/ethnicity, the highest level of education, marital status, and the ratio of family income to poverty. Race/ethnicity was combined into four categories White, non-Hispanic, Black, non-Hispanic, Hispanic, Asian, non-Hispanic, and Other race, non-Hispanic. SAS provided the values for the variable poverty to reflect the median value of the responses. Poverty was divided into <1.96 and ≥1.96 to reflect <1.0 as low poverty and ≥1.0 as high poverty. Marital status was recoded to reflect as Married/Living with Partner and Not Married/Widowed/Divorced/Separated. The categories for the highest level of education, adult food security, and household food security will stay the same as the original dataset.

A Chi-Square Test of Independence was used to examine the relationship between the supplementation of Vitamins D and B6 and Magnesium and the symptoms of depression. Additionally, a logistic regression analysis was completed to assess the nutritional status of Magnesium and Vitamins D and B6 on depression symptoms when adjusted for age, sex, race, and socioeconomic status. Descriptions of confounders, independent and dependent variables that provide the rationale for considering these variables, along with NHANES survey year availability, are labeled in appropriate tables [28,29,30]. The categorical intakes for vitamins D, B6, and Magnesium were organized into binary categories provided by SAS. P < .05 was used to account for statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

Baseline characteristics of the study population include the demographic, dietary, and socioeconomic characteristics of the entire study (n = 8544). Among the respondents at baseline, 14.70% (n=837) reported that they had symptoms of depression during the two weeks leading up to their physical examination, while 85.30% responded that they did not experience any symptoms of depression. The average age of the sample size was 48.41 years. Individuals who responded as having depressive symptoms were white, non-Hispanic (63.60%) females (60.86%), the majority of whom were married (65.14%) when examined by depression. Additionally, a larger number of individuals who disclosed having depressive symptoms was in the “Some college or AA degree” category (34.88%), whereas “Less than 9th grade” was the lowest (5.11%).

Although there were a few differences found between the vitamins and minerals, there was a large number of missing responses, for example, there were 6500 missing responses for the amount of magnesium (mg) the individual took, while there were 5251 missing responses for vitamin D. These differences show that more people who reported symptoms had low vitamin D (25.44%) compared to vitamin B6 and magnesium (20.07% and 23.54%). The opposite was true for no symptoms of depression, 33.56% reported low vitamin D and no depression, while 29.75% had low vitamin B6. Table 1 presents the demographic, dietary, and socioeconomic characteristics of the study population stratified by symptoms of depression.

Results of the Chi-Square Test showed a significant association between depression and a few of the vitamins and minerals that exist. There was a significant association between vitamin B6 and symptoms of depression (χ²=4.4207, 𝘱=0.0355). 8.19% of individuals had low vitamin B6 and had symptoms of depression. There was also a significant association between magnesium and depression (χ²=45.1914, 𝘱=0.00227). In addition, 9.03% of respondents had low magnesium intake with depression symptoms. Lastly, vitamin D was borderline statistically significant with depression (χ²=3.6661, 𝘱=0.0555). Whereas, 9.40% of individuals reported low vitamin D and symptoms of depression.

3.2. Vitamin Intake and Depression

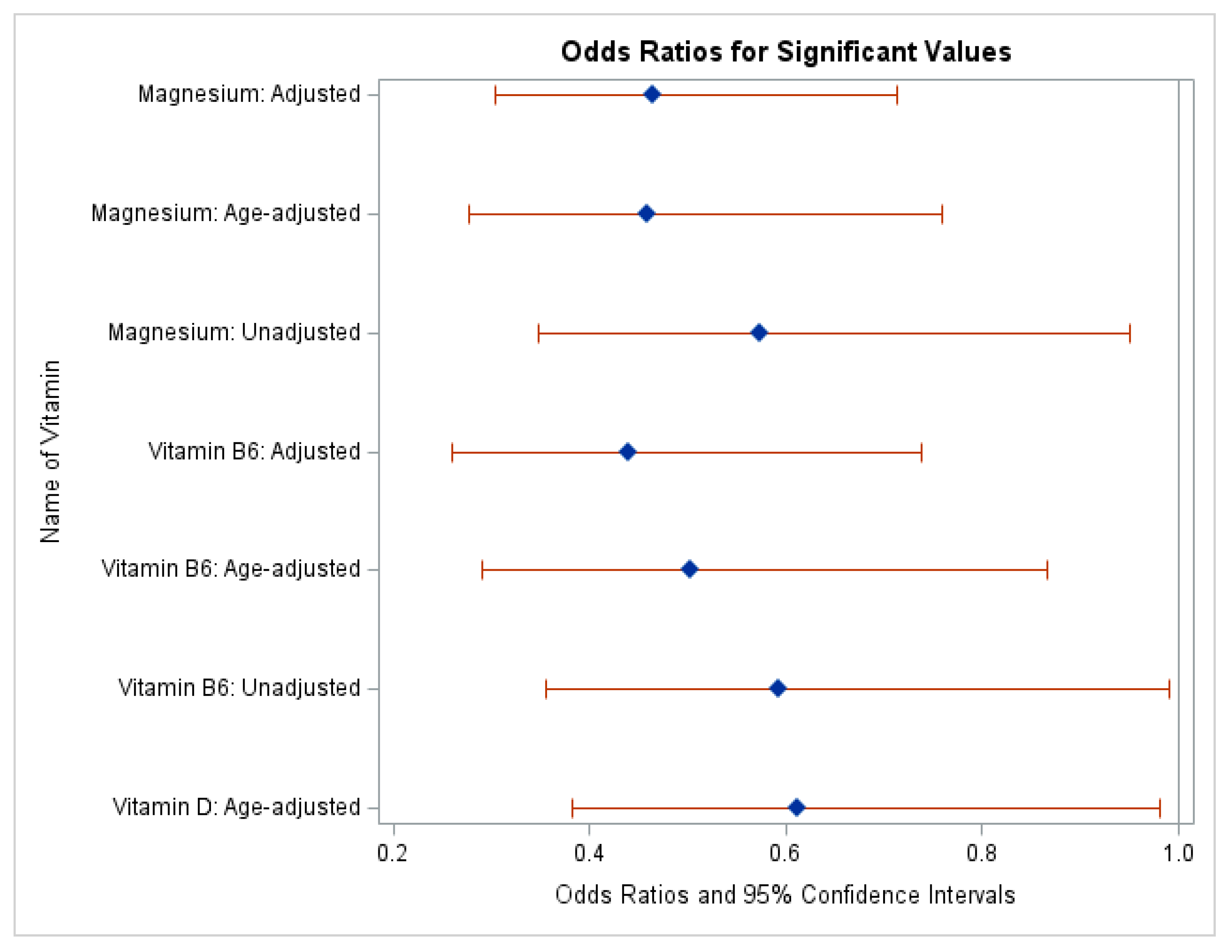

The results of the logistic regression analysis examined the relationship between depressive symptoms and the dietary intake of vitamins D, B6, and magnesium. The unadjusted model showed that low vitamin B6 correlates with an increase in depressive symptoms (OR=0.593, 95% CI 0.355-0.991) and that low magnesium correlates with an increase in depressive symptoms (Magnesium: OR=0.574, 95% CI 0.347-0.951). The age-adjusted model showed that low vitamin D, low vitamin B6, and magnesium showed a correlation on depressive symptoms (Vitamin D: OR=0.611, 95% CI 0.382-0.980 Vitamin B6: OR=0.503, 95% CI 0.291-0.867 Magnesium: OR=0.458, 95% CI 0.277-0.759). However, the fully adjusted regression model shows that low intake of vitamin B6 correlates with an increase in depressive symptoms (Vitamin B6: OR=0.439, 95% CI 0.260-0.738 Magnesium: OR=0.465, 95% CI 0.303-0.714). When adjusted for all covariates, vitamin D was not statistically significant with depression (Vitamin D: OR=1.613, 95% CI 0.991-2.625). Table 2 provides an overview of the significant and insignificant odds ratio and confidence intervals for the relationship between vitamin D, B6, and magnesium on symptoms of depression.

Figure 1 shows a visual representation of the significant odds ratios in Table 2 presented as a forest plot labeled as the unadjusted, age-adjusted, and fully adjusted models. This forest plot only shows the significant odds ratios from Table 2 above.

The results of the fully-adjusted model showed no association between the symptoms of depression and a lower intake of vitamin D when adjusted for covariates (Vitamin D: OR=0.981, 95% CI 0.476-2.020). Moreover, when adjusted for all covariates, low magnesium showed a relationship with symptoms of depression (Magnesium: OR=0.846 95% CI 0.389-1.839). When adjusted for all covariates, low intake of vitamin B6 showed a correlation for symptoms of depression (Vitamin B6: OR=0.408 95% CI 0.169-0.986). Only vitamin B6 showed a relationship in the age-adjusted model when vitamin D and magnesium were included in the model as covariates (Vitamin B6: OR=0.439 95% CI 0.200-0.963). Odds ratios for unadjusted, age-adjusted, and fully-adjusted models for the combination of vitamins D, B6, and magnesium on the presence of depression symptoms are shown in Table 3.

4. Discussion

Data from NHANES were used to evaluate if there was an association between dietary intake with supplementation of vitamin D, vitamin B6, and magnesium on depressive symptoms in adults aged 20 years and older living in the US. The results showed a significant association between depression and vitamin B6 intake. Finally, the results of the analysis also showed that there was an association between magnesium intake and depression. The results of the unadjusted model did not show a relationship between vitamin D intake and depression.

The findings showed that there were significant differences between vitamin D, vitamin B6, and magnesium as it relates to depressive symptoms when adjusting for covariates. When adjusted for age, a lower intake of vitamin D, B6, and magnesium showed an increase of depressive symptoms. When adjusting for the potential confounders, only vitamin B6 and magnesium were identified as having an increase of depressive symptoms. Additionally, looking at the effects of vitamin D, vitamin B6, and magnesium intake when analyzed together, the results showed only vitamin B6 was significant for reducing depressive symptoms. However, these results demonstrate that intake of vitamin B6 and magnesium on depressive symptoms is important when considering age and other sociodemographic factors.

Evidence was provided for the association between vitamin supplementation and the prevalence of depression among adults over the age of 20 in the 2017-March 2020 NHANES database. From current knowledge, this present study is the first to explore the specific dietary composition of vitamins and minerals and their association with depressive symptoms in adults. These results show that there are possible alternative methods to preventing depression and other mental health disorders through natural over-the-counter remedies rather than prescribed antidepressants. More research is needed to be done regarding the effectiveness of taking daily vitamin supplements apart from the elements present in their meals. Such that everyone is given a daily oral dose of vitamin B6 to supplement the vitamin B6 they are already getting from their food.

The definition of adequate dietary intake of vitamins and minerals in reducing symptoms of depression and other mental health-related still remains unclear. Food insecurity is a critical public health problem that contributes to poor diet quality and other health imbalances [4]. Feeding America (n.d.) defined food insecurity as “the lack of consistent access to enough food for every person in a household to live an active, healthy life”. In the US, about 11% of households reported being food insecure before the pandemic, while many states saw household food insecurity well above the national average [33]. Given the impact of financial assets on food security and mental health separately, it is suggested that there is great importance in controlling financial resources relevant for mental health [34]. Food insecurity has been reported to be negatively associated with psychological well-being [35]. Food insecurity and diet quality are related when identifying how nutrient supplementation can provide the best results for mental health issues [8,16,18]. Food insecurity contributes to issues of psychological acceptability, such that an individual can experience feelings of deprivation or restricted food choice and anxiety about food supplies as a result of being food insecure [33,34,35]. Food insecurity is tied to a higher likelihood of being extremely concerned about the effect of COVID on health, income, daily life, the economy, and the ability to feed one’s family [4,33,34,35].

The Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP) is among the largest federal food and nutrition assistance programs to address food insecurity through monthly electronic benefits for qualifying low-income households to purchase food [33]. Past studies have considered the role of SNAP in the relationship between food insecurity and maternal depression. In this study, the results showed that after 6 months of participation, fewer households reported psychological distress [4,33]. In another study, the association between food insecurity and depression to determine if the association differed by participation showed that food insecurity was positively associated with depression, but SNAP benefits changed this association by decreasing the magnitude of this relationship [33].

Lifestyle medicine is a term that is defined as the "differences in lifestyle habits such as physical activity, diet, substance use, and sleep, to improve mental health symptoms” [36]. Additionally, nutritional psychiatry is defined as a “specialized field of lifestyle medicine that focuses on the relationship between nutrition and mental health symptoms” [36]. Young et al. (2021a) researched the effects of an app-based program that can promote dietary change and the results showed that participants who changed their diet were more likely to set goals towards changing their eating habits. However, the evidence behind this knowledge has been underappreciated but since the recent pandemic, urbanization and globalization have helped improve the awareness of this field of study [17].

Other studies have looked at the overall impact of changing one’s diet to reflect a lower prevalence of depression symptoms. For example, the My Food and Mood study created by Young and colleagues (2021b) was developed to test the feasibility of digital health Mediterranean dietary intervention for people with higher depression symptoms. The primary aim of this study was to determine whether an app-based program promoted dietary change. There was a significant increase in the scores from baseline to halfway through the program, in which the program showed that it promoted better diet quality [36,37]. Nevertheless, this separate study has limitations to show that it can be improved further to increase engagement, retention, and dietary improvement [36,37]. This can further support future large-scale trials aimed at testing dietary interventions for depression.

Diet modification has been previously used for the prevention of many immune, infectious, and chronic conditions such as COVID-19, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes among many more. Even so, there is a limited understanding of the mechanisms for how diet impacts depression and how the outcomes of an unhealthy diet can influence mental disorders [9]. Proposed nutritional deficiencies and treatments for persons with major depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and obsessive-compulsive disorder have been reported. For example, vitamin D has been linked to seasonal affective disorder (SAD), schizophrenia, and depression, in which the amount of light therapy was examined for mood changes. Partonen et al., (1999) reported that about one hour of light therapy significantly decreases symptoms of depression in patients with SAD compared to those without light therapy. Moreover, a dose-response association between vitamin D levels and depression at their baseline measurement was outlined by Ronaldson et al., (2020). This showed that there was an increased risk of depression among participants with inadequate levels of vitamin D and adequate levels at baseline and at follow-up [25]. However, it is important to make sure it is known that the impact of vitamin D on depression depends on the dose amount that is taken to find differences in mood.

Confirming other studies that also looked at how a non-Western diet can reduce depressive symptoms in adolescents [24]. Excess body weight is an important problem today, where about 30% of the total population is obese [17]. Individuals tend to consume more and more high-energy, processed, and nutrient-poor foods which can contribute to this ongoing epidemic. As a result, less and less fiber and nutrient-rich foods are being consumed. In addition, lifestyle factors such as smoking, sedentary behavior, and alcohol consumption are increasing all over the world, which can all lead to the development of mental health disorders [17]. The finding that vitamin B6 supplementation reduced depression is consistent with the findings in many studies [11]. Looking at the mechanisms, B6 is among other B vitamins that are essential for a normal central nervous system and brain function and is shown to control moods through several pathways. B vitamins also play a role in the proper functioning of the nervous tissue [17].

Noah et al. (2021) discovered that magnesium, with or without additional supplementation of B6, improved mood and anxiety in healthy adults, which aligns with the results of this research. The authors of this study also tested how baseline depression would be improved based on scores from an anxiety scale to identify changes. The findings of this study support other findings in which magnesium as a treatment for improving stress-related depression in individuals with a deficiency of vitamin B6 can reduce symptoms of depression [13]. In addition, magnesium ions regulate calcium ion flow in neuronal calcium channels, helping to regulate neuronal nitric oxide production, which is very important for the brain’s chemistry [10].

Strengths and Limitations

Although this study showed a difference in low intake of vitamins and minerals as an indicator of depression, there are several strengths and limitations to this study. One limitation is the difference in sample sizes between the participants who responded for each of the vitamins/minerals. The distribution of responses showed notable differences between the groups in comparison to the initial sample size of this dataset. However, the sample size for magnesium collected significantly fewer responses, making it difficult to draw valid conclusions regarding the data. This limitation shows that the results cannot be generalizable to the rest of the population, as many responses were missing for each predictor variable. This limitation can also be attributed to lower statistical power and reduced effect size in this study.

Furthermore, there is a possibility of survey bias for responses of the predictor variables in which many respondents were not candid on their questionnaire. Even so, NHANES used a Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) to assess all the vitamins and minerals. FFQs are not always valid to determine if the recommended daily amount of essential vitamins and minerals are met. Future research could only look at the supplementation of these three vitamins/minerals for deficient and adequate adults and ensure that the participants are truthful. This can be combated by the use of a 24-hour dietary recall form. These vast differences in sample size also prevented each of the vitamins/minerals from being analyzed together with the addition of covariates. However, the initial sample size used for the start of this analysis was a strength in evaluating the effectiveness of sociodemographic variables in the regression analysis.

Another limitation of the study was that there is no standard way to measure if they are eating enough vitamin D, vitamin B6, and magnesium from their food. This type of measurement would have to be very distinct in that individuals must know the amount of each vitamin or mineral in each ingredient of the meals they eat. Many people do not have the patience or knowledge for identifying the nutritional value of each ingredient they use. To resolve this, future studies should determine if individual supplementation of vitamins D, B6, and magnesium is more effective at reducing symptoms where symptoms first arrive. Additionally, the dataset did not provide a clear indication of how each vitamin and mineral intake was calculated based on individual dietary or supplement intakes.

In contrast, this study did not have evidence that showed changes in symptoms from the use of vitamin D. Future studies are required to clarify the association of vitamin D and depression, as in the literature few studies show there is an association while some do not [12,25,26]. Furthermore, specific case-control or prospective cohort studies may be valuable for understanding the precise effect vitamins D, B6 and magnesium have on the prevalence of depression symptoms.

5. Conclusions

The nature of one’s diet and its repercussions on health are characterized in mental health as a public health problem. Numerous investigations provide reassurance for the existence of direct relationships between nutrition, stress susceptibility, mental health, and mental function. The reviewed literature expressed the importance of nutrients, vitamins, and minerals included, in the prevention and treatment of symptoms of depression [8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. Research shows that many individuals who reported the development of depression symptoms have a deficiency in nutrients [8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. However, the relationship between diet, obesity, stress, and stress-related psychiatric disorders is complex [11,24].

The data support the hypothesis that there is a relationship between varying intakes of vitamins and minerals on symptoms of depression. This association was particularly evident for lower intakes of both vitamin B6 and magnesium when adjusted for age, and sociodemographic covariates. These findings indicate the need for further research on the impact of diet on mental health. Future prospective cohort studies exploring these associations, with a focus on daily dietary intake, are needed to further validate the direction of causation and understand the underlying mechanisms.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.R.; methodology, R.R.; formal analysis, R.R..; data curation, R.R.; writing—original draft preparation, R.R., K.B., J.V., and N.A.; writing—review and editing, R.R., K.B., J.V., and N.A.; visualization, R.R.; supervision, K.B., J.V., and N.A.; project administration, R.R., K.B., J.V., and N.A.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Grand Valley State University on 21 December 2021 (protocol code: IRB 23-134-H).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- National Insititute of Environmental Health Sciences. (n.d.). Nutrition, Health, and Your Environment. https://www.niehs.nih.gov/health/topics/nutrition/index.cfm.

- Dimitratos, S. (2018, October 1). Food and mood: What is nutritional psychiatry? American Society for Nutrition. https://nutrition.org/food-and-mood-what-is-nutritional-psychiatry/.

- Hanson-Baiden, J. (2022, January 18). What is Nutritional Psychiatry? News-Medical.Net. https://www.news-medical.net/health/What-is-Nutritional-Psychiatry.aspx.

- Wolfson, J. A. , Garcia, T., & Leung, C. W. (2021). Food insecurity is associated with depression, anxiety, and stress: Evidence from the early days of the COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States. Health Equity, 5(1), 64–71. [CrossRef]

- Meegan, A. P. , Perry, I. J., & Phillips, C. M. (2017). The association between dietary quality and dietary guideline adherence with mental health outcomes in adults: A cross-sectional analysis. Nutrients, 9(3), 238. [CrossRef]

- Rahe, C. , Baune, B. T., Unrath, M., Arolt, V., Wellmann, J., Wersching, H., & Berger, K. (2015). Associations between depression subtypes, depression severity and diet quality: Cross-sectional findings from the BiDirect Study. BMC Psychiatry, 15, 38. [CrossRef]

- Opie, R. S. , Itsiopoulos, C., Parletta, N., Sanchez-Villegas, A., Akbaraly, T. N., Ruusunen, A., & Jacka, F. N. (2017). Dietary recommendations for the prevention of depression. Nutritional Neuroscience, 20(3), 161–171. [CrossRef]

- Botturi, A. , Ciappolino, V., Delvecchio, G., Boscutti, A., Viscardi, B., & Brambilla, P. (2020). The role and the effect of magnesium in mental disorders: A systematic review. Nutrients, 12(6), 1661. [CrossRef]

- Bremner, J. D. , Moazzami, K., Wittbrodt, M. T., Nye, J. A., Lima, B. B., Gillespie, C. F., Rapaport, M. H., Pearce, B. D., Shah, A. J., & Vaccarino, V. (2020). Diet, stress and mental health. Nutrients, 12(8), Article 8. [CrossRef]

- Eby, G. A., & Eby, K. L. (2006). Rapid recovery from major depression using magnesium treatment. Medical Hypotheses, 67(2), 362–370. [CrossRef]

- Field, D. T. , Cracknell, R. O., Eastwood, J. R., Scarfe, P., Williams, C. M., Zheng, Y., & Tavassoli, T. (2022). High-dose vitamin B6 supplementation reduces anxiety and strengthens visual surround suppression. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental, 37(6), e2852. [CrossRef]

- Menon, V. , Kar, S. K., Suthar, N., & Nebhinani, N. (2020). Vitamin D and Depression: A Critical Appraisal of the Evidence and Future Directions. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 42(1), 11–21. [CrossRef]

- Noah, L. , Dye, L., Bois De Fer, B., Mazur, A., Pickering, G., & Pouteau, E. (2021). Effect of magnesium and vitamin B6 supplementation on mental health and quality of life in stressed healthy adults: Post-hoc analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Stress and Health, 37(5), 1000–1009. [CrossRef]

- Penckofer, S. , Kouba, J., Byrn, M., & Ferrans, C. E. (2010). Vitamin D and depression: Where is all the sunshine? Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 31(6), 385–393. [CrossRef]

- Adan, R. A. H. , van der Beek, E. M., Buitelaar, J. K., Cryan, J. F., Hebebrand, J., Higgs, S., Schellekens, H., & Dickson, S. L. (2019). Nutritional psychiatry: Towards improving mental health by what you eat. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 29(12), 1321–1332. [CrossRef]

- Godos, J. , Currenti, W., Angelino, D., Mena, P., Castellano, S., Caraci, F., Galvano, F., Del Rio, D., Ferri, R., & Grosso, G. (2020). Diet and mental health: Review of the recent updates on molecular mechanisms. Antioxidants, 9(4), Article 4. [CrossRef]

- Grajek, M. , Krupa-Kotara, K., Białek-Dratwa, A., Sobczyk, K., Grot, M., Kowalski, O., & Staśkiewicz, W. (2022). Nutrition and mental health: A review of current knowledge about the impact of diet on mental health. Frontiers in Nutrition, 9. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2022.943998. 9439. [Google Scholar]

- Kris-Etherton, P. M. , Petersen, K. S., Hibbeln, J. R., Hurley, D., Kolick, V., Peoples, S., Rodriguez, N., & Woodward-Lopez, G. (2021). Nutrition and behavioral health disorders: Depression and anxiety. Nutrition Reviews, 79(3), 247–260. [CrossRef]

- Selhub, E. (2015, November 16). Nutritional psychiatry: Your brain on food. Harvard Health. https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/nutritional-psychiatry-your-brain-on-food-201511168626.

- O’Neil, A. , Berk, M., Itsiopoulos, C., Castle, D., Opie, R., Pizzinga, J., Brazionis, L., Hodge, A., Mihalopoulos, C., Chatterton, M. L., Dean, O. M., & Jacka, F. N. (2013). A randomised, controlled trial of a dietary intervention for adults with major depression (the “SMILES” trial): Study protocol. BMC Psychiatry, 13, 114. [CrossRef]

- Roca, M. , Gili, M., Garcia-Garcia, M., Salva, J., Vives, M., Garcia Campayo, J., & Comas, A. (2009). Prevalence and comorbidity of common mental disorders in primary care. Journal of Affective Disorders, 119(1–3), 52–58. [CrossRef]

- Gorwood, P. (2010). Restoring circadian rhythms: A new way to successfully manage depression. Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), 24(2 Suppl), 15–19. [CrossRef]

- Bekdash, R. A. (2021). Early life nutrition and mental health: The role of DNA methylation. Nutrients, 13(9), Article 9. [CrossRef]

- Herbison, C. E. , Hickling, S., Allen, K. L., O’Sullivan, T. A., Robinson, M., Bremner, A. P., Huang, R.-C., Beilin, L. J., Mori, T. A., & Oddy, W. H. (2012). Low intake of B-vitamins is associated with poor adolescent mental health and behaviour. Preventive Medicine, 55(6), 634–638. [CrossRef]

- Ronaldson, A. , Arias de la Torre, J., Gaughran, F., Bakolis, I., Hatch, S., Hotopf, M., & Dregan, A. (2022). Prospective associations between vitamin D and depression in middle-aged adults: Findings from the UK Biobank cohort. Psychological Medicine, 52(10), 1866-1874. [CrossRef]

- Partonen, T. , Vakkuri, O., Lamberg-Allardt, C., & Lonnqvist, J. (1996). Effects of bright light on sleepiness, melatonin, and 25-hydroxyvitamin D(3) in winter seasonal affective disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 39(10), 865–872. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). About NHANES. National Center for Health Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/about_nhanes.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021a). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data (NHANES): Demographics Data. [Dataset and codebook]. National Center for Health Statistics. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/search/datapage.aspx?Component=Demographics&Cycle=2017-2020.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021b). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data (NHANES): Dietary Data. [Dataset and codebook]. National Center for Health Statistics. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/search/datapage.aspx?Component=Dietary&Cycle=2017-2020.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021c). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data (NHANES): Questionnaire Data. [Dataset and codebook]. National Center for Health Statistics. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/search/datapage.aspx?Component=Questionnaire&Cycle=2017-2020.

- Spitzer, R. L. , Kroenke, K., & Williams, J. B. (1999). Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA, 282(18), 1737–1744. [CrossRef]

- Feeding America. (n.d.). What is Food Insecurity? https://www.feedingamerica.org/hunger-inamerica/food-insecurity.

- Myers, C. A. (2020). Food Insecurity and Psychological Distress: A Review of the recent literature. Current Nutrition Reports, 9(2), 107–118. [CrossRef]

- Yenerall, J. , & Jensen, K. (2022). Food Security, Financial Resources, and Mental Health: Evidence during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nutrients, 14(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H. , & Singh, G. K. (2022). Food insecurity–Related interventions and mental health among US adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic, April 2020 through August 2021. Public Health Reports, 137(6), 1187–1197. [CrossRef]

- Young, C. L. , Mohebbi, M., Staudacher, H., Berk, M., Jacka, F. N., & O’Neil, A. (2021a). Assessing the feasibility of an m-Health intervention for changing diet quality and mood in individuals with depression: The My Food & Mood program. International Review of Psychiatry, 33(3), 266–279. [CrossRef]

- Young, C. , Mohebbi, M., Staudacher, H., Kay-Lambkin, F., Berk, M., Jacka, F., O'Neil, A. (2021b). Optimizing engagement in an online dietary intervention for depression (My Food & Mood Version 3.0): Cohort Study. JMIR Mental Health, 8 (3), e24871. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Odds ratios and 95% CIs for the association of vitamin D, vitamin B6, and magnesium on symptoms of depression among individuals over the age of 20, NHANES study (n=8544).

Figure 1.

Odds ratios and 95% CIs for the association of vitamin D, vitamin B6, and magnesium on symptoms of depression among individuals over the age of 20, NHANES study (n=8544).

Table 1.

Characteristics of individuals by the presence of symptoms indicated by vitamin D, B6, and magnesium dosages, NHANES (n=8544).

Table 1.

Characteristics of individuals by the presence of symptoms indicated by vitamin D, B6, and magnesium dosages, NHANES (n=8544).

| Variables | Total (n = 8544) |

Depression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Statistics | p | ||

| Age at screeninga, mean(SD) | 48.41(0.52) | 46.44(0.52) | 47.70(0.66) | ||

| Gendera, n (%), n (%) | |||||

| Male | 4135(48.12) | 325(39.14) | 2022(44.52) | ||

| Female | 4409(51.88) | 512(60.86) | 2379(55.48) | ||

| Ethnicitya, n (%), n (%) | |||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 2932(62.57) | 318(63.60) | 1648(64.76) | ||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 2291(11.47) | 216(10.99) | 1151(10.85) | ||

| Hispanic | 1875(15.97) | 190(15.27) | 946(115.67) | ||

| Asian, non-Hispanic | 1037(5.97) | 42(2.51) | 434(4.68) | ||

| Other race, non-Hispanic | 409(4.02) | 71(7.63) | 222(4.04) | ||

| Marital Status, n (%), n (%) | |||||

| Married/Living with Partner | 4919(76.80) | 365(65.14) | 2469(75.91) | ||

| Not Married/Widowed/Divorced/Separated | 1951(23.20) | 272(34.86) | 1018(24.09) | ||

| Missing | 1674 | 200 | 914 | ||

| Education, n (%), n (%) | |||||

| Less than 9th Grade | 666(3.78) | 80(5.11) | 254(2.77) | ||

| 9-11th Grade | 947(7.27) | 123(9.56) | 461(6.70) | ||

| HS graduate/GED | 2060(26.96) | 232(32.13) | 1052(26.51) | ||

| Some college or AA degree | 2087(30.46) | 299(34.88) | 1535(31.51) | ||

| College graduate or above | 8531(31.53) | 101(18.32) | 1097(32.51) | ||

| Missing | 13 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Vitamin D, n (%), n (%) | χ²=3.6661 | 𝘱=0.0555 | |||

| Low | 1133(32.17) | 94(25.44) | 612(33.56) | ||

| High | 2160(67.83) | 210(74.56) | 1123(66.44) | ||

| Missing | 5251 | 533 | 2666 | ||

| Vitamin B6, n(%), n(%) | χ²=4.4207 | 𝘱=0.0355 | |||

| Low | 749(27.69) | 56(20.07) | 417(29.75) | ||

| High | 1810(72.31) | 162(79.93) | 946(70.25) | ||

| Missing | 5985 | 619 | 3038 | ||

| Magnesium, n (%), n (%) | χ²=45.1914 | 𝘱=0.0227 | |||

| Low | 664(31.12) | 53(23.54) | 376(34.90) | ||

| High | 1380(68.88) | 137(76.46) | 706(65.10) | ||

| Missing | 6500 | 647 | 3319 | ||

| Ratio of family income to poverty, n (%), n (%) | |||||

| Low poverty | 3312(31.15) | 464(51.64) | 376(34.90) | ||

| High poverty | 4037(68.85) | 256(48.36) | 706(65.10) | ||

| Missing | 1674 | 117 | 535 | ||

| Household food security, n (%), n (%) | |||||

| Full security:0 | 4955(71.73) | 310(47.92) | 2567(72.04) | ||

| Marginal security:1-2 | 1151(11.09) | 124(14.15) | 610(11.36) | ||

| Low security:3-5(w/o child)/3-7(w/child) | 1146(10.45) | 163(18.46) | 599(10.25) | ||

| Very low security:6-10(w/o child)/8-18(w/child) | 750(6.74) | 188(19.47) | 379(6.35) | ||

| Missing | 52 | 246 | |||

| Adult food security, n(%), n(%) | |||||

| Full security:0 | 4988(72.07) | 312(48.30) | 2588(72.48) | ||

| Marginal security:1-2 | 1193(11.39) | 132(14.57) | 624(11.44) | ||

| Low security:3-5 | 1023(9.08) | 140(16.09) | 535(8.74) | ||

| Very low security:6-10 | 798(7.46) | 201(21.03) | 408(7.35) | ||

| Missing | 542 | 52 | 246 | ||

| Depression, n(%) | |||||

| No Depression | 4401(85.30) | ||||

| Depression | 837(14.70) | ||||

| Missing | 3306 | ||||

N=837 reflects the number of individuals who responded as having depressive symptoms and N=4401 reflects the number of participants who responded as not having depressive symptoms. a There were no missing data for this variable.

Table 2.

Odds ratios and 95% CIs for the association between vitamin D, B6, and magnesium on symptoms of depression among individuals over the age of 20, NHANES (n=8544).

Table 2.

Odds ratios and 95% CIs for the association between vitamin D, B6, and magnesium on symptoms of depression among individuals over the age of 20, NHANES (n=8544).

| Presence of Depression | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Modela | Adjusted Modelb | Adjusted Modelc | ||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| High Vitamin D | 1.00 | (reference) | 1.00 | (reference) | 1.00 | (reference) |

| Low Vitamin D | 0.676 | (0.442-1.032) | 0.611 | (0.382-0.980) | 0.620 | (0.381-1.009) |

| High Vitamin B6 | 1.00 | (reference) | 1.00 | (reference) | 1.00 | (reference) |

| Low Vitamin B6 | 0.593 | (0.355-0.991) | 0.503 | (0.291-0.867) | 0.439 | (0.260-0.738) |

| High Magnesium | 1.00 | (reference) | 1.00 | (reference) | 1.00 | (reference) |

| Low Magnesium | 0.574 | (0.347-0.951) | 0.458 | (0.277-0.759) | 0.465 | (0.303-0.714) |

a Not adjusted for any covariates; b Age-adjusted model; Adjusted for the following covariates: age at screening, gender, ethnicity, marital status, education, the ratio of family income to poverty, household food security, and adult food security.

Table 3.

Odds ratios and 95% CIs for the association of vitamin D, vitamin B6, and magnesium combined on symptoms of depression among individuals over the age of 20, NHANES study (n=8544).

Table 3.

Odds ratios and 95% CIs for the association of vitamin D, vitamin B6, and magnesium combined on symptoms of depression among individuals over the age of 20, NHANES study (n=8544).

| Presence of Depression | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Modela | Age-Adjusted Modelb | Adjusted Modelc | |||||

| n | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| High Vitamin D, Vitamin B6, Magnesium | 210 162 137 |

1.00 | (reference) | 1.00 | (reference) | 1.00 | (reference) |

| Low Vitamin D, Vitamin B6, Magnesium | 94 56 53 |

0.866 0.471 0.906 |

(0.484-1.551) (0.211-1.054) (0.438-1.873) |

0.787 0.439 0.801 |

(0.426-1.454) (0.200-0.963) (0.395-1.622) |

0.981 0.408 0.846 |

(0.476-2.020) (0.169-0.986) (0.389-1.839) |

a Not adjusted for any covariates; b Age-adjusted model; c Adjusted for the following covariates: age at screening, gender, ethnicity, marital status, education, the ratio of family income to poverty, household food security, and adult food security. N=Number of cases for each vitamin that reported symptoms of depression.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Copyright: This open access article is published under a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license, which permit the free download, distribution, and reuse, provided that the author and preprint are cited in any reuse.

MDPI Initiatives

Important Links

© 2024 MDPI (Basel, Switzerland) unless otherwise stated