Preprint

Article

Psychometric Properties and Screening Performance of the Geriatric Depression Scale in a Mild-to-Moderate Cognitively Impaired Portuguese Sample

Altmetrics

Downloads

141

Views

64

Comments

0

A peer-reviewed article of this preprint also exists.

This version is not peer-reviewed

Submitted:

13 June 2023

Posted:

13 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Alerts

Abstract

Although the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) is a well-established instrument for the assessment of depressive symptoms in older adults, this has not been validated specifically for Portuguese cognitively impaired persons. The objective of this study was to analyze the psychometric properties of two Portuguese versions of the GDS (GDS-27 and GDS-15) in a Portuguese mild-to-moderate cognitively impaired sample. Clinicians assessed for major depressive disorder and cognitive functioning in 117 participants with mild to moderate cognitive decline (76.9% female, Mage = 83.66 years). The internal consistency of GDS-27 and GDS-15 were 0.874 and 0.812, respectively. There was a significant correlation between GDS-27 and GDS-15 with Beck Depression Inventory-II GDS-27: rho = 0.738, p < 0.001; GDS-15: rho = 0.760, p < 0.001), suggesting good validity. A cutoff point of 15/16 in GDS-27 and 8/9 in GDS-15 resulted in identification of persons with depression (GDS-27: sensitivity 100%, specificity 63%; GDS-15: sensitivity 90%, specificity 62%). Overall, the GDS-27 and GDS-15 are reliable and valid instruments for the assessment of depression in Portuguese-speaking cognitively impaired persons.

Keywords:

Subject: Social Sciences - Psychiatry and Mental Health

1. Introduction

Population ageing is occurring globally at an unprecedented rate and will accelerate in the coming decades, particularly in developing countries (World Health Organization [WHO], 2020). The WHO estimates that the number of older adults aged 60 and over will reach up to 2.1 billion worldwide by 2050, with nearly 80% stemming from low- and middle-income countries (WHO, 2018). According to data from the Statistics National Institute (SNI), older adults in Portugal comprise approximately 21.5% of the population, with an expected increase to 37.2% by 2080 (SNI, 2019).

Older adults, with non-normative aging, are particularly vulnerable to mental and neurological health conditions such as neurocognitive disorders and depression, due to additional stress factors such as loss of capacity (Ferenchick et al., 2019). The effects of depression can be chronic or recurrent and can dramatically affect an individual's daily functioning and quality of life (WHO, 2020). Additionally, when depression is associated with chronic illness, it increases morbidity and mortality, leading to psychological and financial burden on the individual, family, and health system (Ozaki et al., 2015). Thus, the health status of older adults has significant personal, community, and national impacts.

The clinical manifestations of depression in older adults are complex as they involve biological, psychological, and social aspects, often related to lifestyle changes and cognitive decline (Drago & Martins, 2012). Identifying depression in the context of primary care, particularly in patients with multiple comorbidities, also can be difficult. As a consequence, depression is often under-diagnosed and under-treated in older adults (Allan et al., 2014). Therefore, self-response questionnaires have emerged as an approach to help primary care providers to identify patients who may have depression but who do not yet have a diagnosis (Ferenchick et al. 2019).

Two existing gold standard instruments for assessing depression throughout the lifespan include the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) originally developed by Beck et al. (1961) and for older adults, the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), created by Yesavage et al. (1983), (American Psychological Association, 2020). The GDS is a widely-used tool for depression screening, specifically designed for the elderly. This instrument does not contain somatic symptomatology assessment items (unlike other depression screening tools) on the grounds that these may lack discriminatory capacity in the older adults because they can be attributed to comorbid physical conditions and the ageing process (Yesavage et al., 1983). Thus, this measure can be administered to older adults regardless of physical illness or cognitive impairment (Krishnamoorthy et al., 2019) and is a reliable screening tool for depressive symptoms in mild cognitive impairment (Debruyne et al., 2009) and dementia (Debruyne et al., 2009; Havins et al., 2012; Lach et al., 2010). Additionally, the format of the GDS includes dichotomous yes/no items, rather than the multi-level items in the BDI-II and has a reduced retrospective recall time span (1 week for the GDS versus 2 weeks for the BDI-II) making it a more simplified tool for older adults.

The original version of GDS has 30 items [GDS-30], though shorter forms (15 items [GDS-15]; 10 items [GDS-10]; 4 items [GDS-4]) have been developed (Sheikh & Yesavage, 1986). These versions have been translated in multiple languages (e.g., Durmaz et al., 2018; Galeoto et al., 2018; Sugishita et al., 2017) including Portuguese (Apóstolo et al., 2014; Apóstolo et al., 2018a, 2018b; Pocinho et al., 2009; Sousa et al., 2007), which is the primary focus of the current study. Systematic reviews of the Portuguese translated briefer versions have been conducted to determine their diagnostic accuracy, validity, and reliability with good support for both in these versions (Almeida et al., 1999; Krishnamoorthy et al., 2019; Li et al., 2015; Mitchell et al., 2010; Weeks et al., 2003). The conclusion was that shorter versions of GDS can be administered for depression screening in primary care and in a community setting and are more efficient than longer forms that carry redundant items (Almeida & Almeida, 1999; Krishnamoorthy et al., 2019; Li et al., 2015; Pocklington et al., 2016).

In Portugal, the GDS-30 was adapted and validated by Pocinho et al. (2009), while a 15 item (GDS-15) version was adapted and validated by Apóstolo et al. (2014, 2018a). Both versions demonstrated good psychometric properties and hence present with potential as a sound instrument for screening for depressive symptoms in older adults. However, these have not been validated specifically in Portuguese cognitively impaired samples.

The aim of this study was to explore the psychometric properties of two Portuguese versions of the GDS (GDS-30 and GDS-15) in a Portuguese mildly-to-moderately cognitively impairment sample, and to compare their performance to DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for major depressive episode. Notably, we used the GDS-30 version in the current study as modified in Pocinho et al. (2009), in which item-level performance revealed that three items on the original GDS-30 (items 27, 29, and 30) were found to be weak in the Portuguese translation; thus our version reflected this psychometrically stronger GDS-27 item version.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted on a convenience sample of 161 older adults recruited through 12 institutions that provide social care and support services for older adults (including people living in long-term care centres, people attending day and social centres and people receiving home support services), located in urban (one in the northern region, and four in the central region) and rural (five in the central region, and two in the southern region) areas of Portugal. To be considered for inclusion in the study, participants had to: (a) be aged 65 years or over; (b) have diagnosis of neurocognitive disorder according to the DSM-5 criteria (APA, 2013) determined by a clinical psychologist; (c) be able to understand and answer the questions integrated in the assessment instruments; and (d) be native Portuguese speakers. Older adults who presented with severe sensory and/or physical limitations, were disconnected from the environment, or had severe neuropsychiatric symptoms that prevented the completion of the assessment instruments, were excluded from the study. Another exclusion criterion took into account the score on the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE; Folstein et al., 1975; Portuguese version by Guerreiro et al., 1994), widely known and used as a screening tool of cognitive function evaluation, interpreted based on normative data for different literacy groups established by Morgado et al. (2009). Score range 0-30. The cutoff points used followed the normative data established by Morgado et al. (2009), and took into account three literacy groups. Namely, in those with 0 to 2 years of formal education, the cutoff point of 22 was used; in those with 3 to 6 years of formal education, the cutoff point of 24 was used; in those with 7 or more years of formal education, the cutoff point of 27 was used. The Portuguese version by Guerreiro et al. (1994) shows good reliability (Cronbach's alpha = .89). It was decided to consider as not eligible for participation the older adults who obtained scores indicating severe cognitive decline (score of less than 9) or scores indicating the absence of significant changes in cognitive functioning (score of 22 for those with 0 to 2 years of formal education, score of 24 for those with 3 to 6 years of formal education and score of 27 for those with 7 or more years of formal education). Of the 161 persons contacted to participate in the study, 44 were excluded (MMSE score did not show significant changes in cognitive functioning), resulting in a final sample of 117 participants. The study was conducted in accordance with the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Health Sciences Research Unit: Nursing, part of the Nursing School of Coimbra (code number P629/11-2019). Participation was voluntary; participants received no financial compensation or any other incentive, and they or their legal representatives gave their informed consent to participate in the study.

2.2. Instruments

A self-reported sociodemographic and clinical questionnaire was administered collecting data on gender, age, marital status, educational level, type of institution attended, presence of medical comorbidities, and cognitive symptoms. In addition, the following self-report assessment tools were used:

Geriatric Depression Scale-30 (GDS-30; Yesavage et al., 1983; Portuguese version by Pocinho et al., 2009): full version, with reported good reliability (Cronbach's alpha = .91). Items are presented in dichotomous format (yes/no). Score range 0-30. Scores of 11 or more out of a maximum of 30 points are suggestive of clinical depression. In the present study, the 27-item version was used. It is easy to administer and is indicated for administration with people suffering from cognitive decline.

Geriatric Depression Scale-15 (GDS-15; Sheikh & Yesavage, 1986; Portuguese version of Apóstolo et al., 2014): 15-item version of the GDS with good reliability (Cronbach's alpha = .83). It consists of 15 questions in a dichotomous format (yes/no). Score range 0-15. Scores equal to or greater than 6 out of a maximum of 15 points are considered to be indicators of depression. The authors suggest that this tool is effective for screening for depression in older adults (Apóstolo et al., 2018a).

Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck et al., 1996; Portuguese version by Campos & Gonçalves, 2011): one of the most widely used tools for assessing self-reported depression, presenting with good reliability (Cronbach's alpha = .90). It consists of 21-items that assesses symptoms characteristic of depression during the last two weeks. It consists of a cognitive-affective scale (items 1-10, 12, 14, and 21) and a somatic scale (items 11, 13, 16-20). Each item is scored from 0 to 3, with 0 reflecting the absence of the symptom and a higher value reflecting greater symptom severity. The overall score ranges from 0 to 63 points. There is evidence that the BDI-II is a reliable and valid tool to be used in screening for depression in older adults, and that it has practical utility in different healthcare contexts (Jefferson et al., 2001; Segal et al., 2008; Steer et al., 2000).

We also administered a module of the Structured Clinical Interview for the Disorders of the DSM-5, Clinician Version (SCID-5-CV) (First et al., 2015), which is based on the DSM-5 criteria (APA, 2013) for depressive disorders, with inter-observer reliability (κ) ranging from 0.70 to 1.00.

2.3. Procedures

The sample was recruited via non-probabilistic sampling among 12 institutions that provide social care and support services for older adults (including people living in long-term care centers, people attending day and social centers and people receiving home support services), located in urban and rural areas of Portugal. The cognitively impaired persons and their legal representatives were contacted, the details of the study were explained to them, and they were invited to participate.

A psychologist with two or more years of experience and familiarity with the measures used in the study asked participants who met the inclusion criteria to complete sociodemographic questionnaire, the Portuguese version of the GDS-27 scale, the Portuguese version of the GDS-15 scale, and the BDI-II (which was used as a gold standard to assess symptoms of depression). In the case where the participants had less reading experience, reading the questions and recording the answers obtained was the responsibility of the professional. A clinical psychologist with two or more years of experience, who had previously undergone training of at least 4 hours, administered the module for major depression of the SCID-5-CV. The clinician was knowledgeable about the results of the GDS and BDI.

The instruments were given in a single session and the order of administration was the following: (1) MMSE, to determine whether they met inclusion criteria of diagnosis of neurocognitive disorder, (2) depression screening instruments, (3) the SCID-5-CV.

2.4. Statistical analysis

To compare the distribution of categorical variables in independent groups, the Chi Squared test was used, with effect size being estimated based on the Phi (φ) statistic for 2x2 contingency tables or on the Cramer´s V statistic for non 2x2 contingency tables. To compare the variance of ordinal variables in independent groups, the Mann-Whitney test (for two groups) and the Kruskal-Wallis test (for more than two groups) were used due to non-normal distribution of the results obtained. In relation to Mann-Whitney test, the effect size was calculated based on a formula “r = Z / √N” and interpreted based on the indications proposed by Cohen (1988). Regarding the Kruskal-Wallis test, if differences were statistically significant, a multiple comparison of mean ranks was performed. The effect size was calculated using the Partial Eta Squared measure (η2p) and interpreted following Cohen’s (1988) and Marôco’s (2011) suggestions.

Internal consistency of GDS questionnaires was measured using Cronbach alpha coefficient. Congruent validity was determined through the Spearman correlation coefficients, calculated for GDS questionnaires and BDI-II.

To analyze the possible effect of covariates on dependent variables, a non-parametric ANCOVA was performed, using the F statistic calculated according to the Quade Method. The Quade Method involves testing the equality of the residuals between groups obtained through linear regression of the ranked dependent variable on the ranked covariate.

The two-factor interaction effect on the dependent variables was also analyzed. For this purpose, a non-parametric two-way ANOVA was performed, using the H statistic calculated based on the formula in which the sum of the squared ranks of a given factor is divided by the total mean square for those ranks. The effect size was indicated by the η2p coefficient.

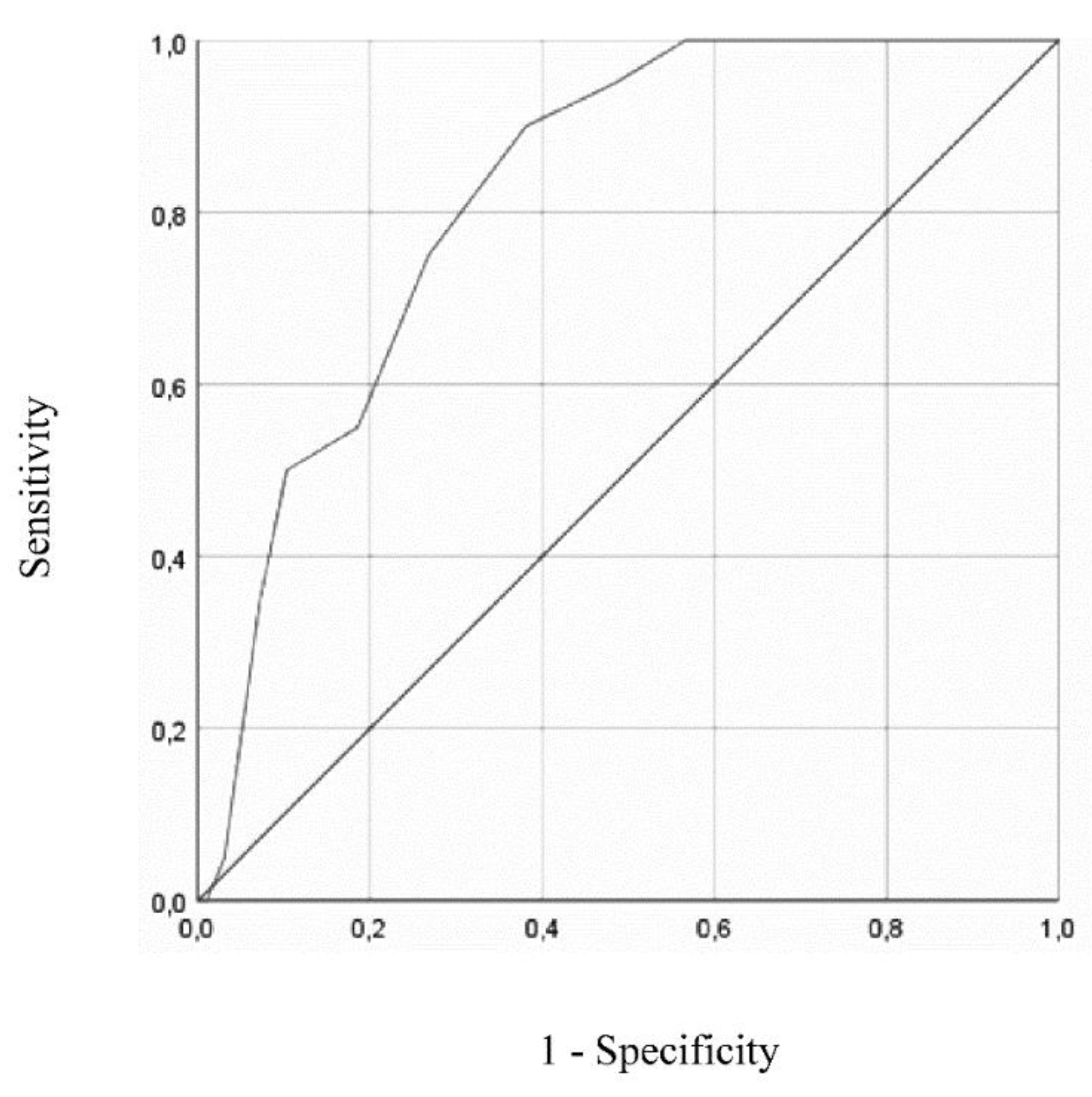

The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for GDS scores and DSM-5 diagnosis (present/absent) was also plotted to establish the sensitivity and specificity of different cut-off points for depression screening. The selection of an optimal cut-off point considered the maximum Youden index, calculated according to a formula “sensitivity + specificity – 1” (Fluss et al., 2005). Other standard summary measures of test accuracy, such as positive and negative predictive values, were also calculated.

In all analyses a statistical significance level of .05 was considered. For data treatment, the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS Statistics, New York), version 25.0, was used.

3. Results

3.1. Sample profile

From 117 older adults are presented in Table 1, applying the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for a major depressive episode, 20 participants were classified as having depression and 97 as not having depression; among depressed participants, 10 met criteria for a mild depressive episode, seven for a moderate depressive episode and three for a severe depressive episode. There were no significant differences between depressed and non-depressed participants in terms of mean age (U(97, 20) = 958.50, p = 0.934), male/female ratio (χ2(1) = 0.887, p = 0.346) and formal education levels ratio (χ2(2) = 5.106, p = 0.078). The groups were also equivalent in terms of MMSE score (U(97, 20) = 961.00, p = 0.948).3.1

3.2. Depressive symptomatology and sociodemographic characteristics

The mean GDS-27 and GDS-15 scores obtained in this sample were 14.11 (SD = 6.68) and 7.68 (SD = 3.75), respectively. Analyses of the potential effect of age, gender and formal education level on the distribution sociodemographic, clinical and neuropsychological characteristics of the participants in the GDS-27 and GDS-15 scores in depressed and non-depressed participants were also performed. To analyze the influence of age, a non-parametric ANCOVA was performed using mean ranks of both the dependent variable and covariate. The F statistic was calculated using the univariate ANOVA of non-standardized residuals obtained through linear regression of the rank of the dependent variable on the rank of the covariate. The F-test showed that the different scores obtained by depressed and non-depressed older adults in both questionaries cannot be explained by age distribution (GDS-27: F=29.657, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.205; GDS-15: F=24.817, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.177).

The potential influence of gender on the variables of interest was analyzed based on a two-factor non-parametric ANOVA. The interaction between the gender group (male/female) and depression group (present/absent) was not statistically significant, independently of the questionnaire used (GDS-27: H(1) = 0.666, p = 0.414; GDS-15: H(1) = 0.147, p = 0.701). In terms of main effects, the depression group-related factor was shown to contribute to the GDS scores distribution (GDS-27: H(1) = 9.215, p = 0.002, η2p= 0.091; GDS-15: H(1) = 9.584, p = 0.002, η2p= 0.092); the same was not verified for the gender group-related factor (GDS-27: H(1) = 0.259, p = 0.610; GDS-15: H(1) = 0.001, p = 0.969). The two-factor non-parametric ANOVA was also used to analyze the potential effect of formal education level on the GDS score distribution in the two participant groups. In both GDS questionnaires, the interaction between the literacy group (0-2 years of formal education / 3-6 years of formal education / 7 or more years of formal education) and depression group (present/absent) showed no influence on the score distribution (GDS-27: H(2) = 0.040, p = 0.841; GDS-15: H(2) = 0.019, p = 0.891). In terms of main effects, the distribution of the GDS score was proved to be influenced by the depression group-related factor (GDS-27: H(1) = 21.592, p < 0.001, η2p= 0.195; GDS-15: H(1) = 19.042, p < 0.001, η2p= 0.174), but not by the literacy group-related factor (GDS-27: H(2) = 2.672, p = 0.263; GDS-15: H(2) = 4.182, p = 0.124).

3.3. Reliability

The reliability of GDS-27 and GDS-15 was calculated based on responses of 94 participants (18 with depression and 76 without depression). As can be seen in Table 2 and Table 3, the GDS-27 item-level means ranged from 0.27 (item 15) to 0.80 (item 17), and the GDS-15 item-level means from 0.21 (item 11) to 0.77 (item 3). In both questionnaires, item-total correlations were predominantly moderate (0.40 < r < 0.70). The inter-item correlation coefficients ranged from 0.206 to 0.766 for GDS-27 and from 0.267 to 0.710 for GDS-15. Internal consistency estimated by Cronbach’s alpha was shown to be high for both versions (GDS-27: α = 0.874; GDS-15: α = 0.812).

3.4. Relationship between GDS and other measures

3.4.1. Convergent validity

The GDS-27 and GDS-15 scores correlated strongly with the BDI-II total score (GDS-27 x BDI-II: rho = 0.738, p < 0.001; GDS-15 x BDI-II: rho = 0.760, p < 0.001). Significant correlations were also found between the scores obtained on the GDS questionnaires and on the BDI-II cognitive-affective and somatic scales; these were of strong and moderate magnitude (GDS-27 x BDI-II cognitive-affective scale: rho = 0.711, p < 0.001; GDS-27 x BDI-II somatic scale: rho = 0.613, p < 0.001; GDS-15 x BDI-II cognitive-affective scale: rho = 0.747, p < 0.001; GDS-15 x BDI-II somatic scale: rho = 0.669, p < 0.001).

3.4.2. GDS-27 and GDS-15 scores in depressed and non-depressed participants

On both GDS questionnaires, non-depressed participants scored lower than depressed ones. The differences observed were statistically significant (GDS-27: U(97, 20) = 298.00, p < 0.001, r = 0.45; GDS-15: U(97, 20) = 347.00, p < 0.001, r = 0.42). The analyses considering non-depressed participants and participants with varying symptom severity also revealed significant between-group differences in the distribution of GDS scores (GDS-27: H(3) = 24.368, p < 0.001; GDS-15: H(3) = 21.850, p < 0.001). According to the pairwise multiple comparisons of mean ranks, on both questionnaires, non-depressed participants scored significantly lower than participants with mild (GDS-27: p < 0.001; GDS-15: p < 0.001), moderate (GDS-27: p < 0.001; GDS-15: p = 0.036) and severe (GDS-27: p = 0.004; GDS-15: p < 0.001) depression. Furthermore, significant differences were found between GDS-15 scores obtained by participants with mild and severe depression (p = 0.001), but not between participants with mild and moderate depression or between participants with moderate and severe depression. In relation to the GDS-27, the scores obtained by participants with varying depression severity did not differ significantly. The effect size calculated for both questionnaires was medium (GDS-27 η2p = 0.210; GDS-15 η2p = 0.188). The corresponding descriptive statistics are presented in Table 4.

3.4.3. Sensitivity and specificity of the GDS-27 and GDS-15

Figure 1 and Figure 2 show the ROC curves for GDS-27 and GDS-15, respectively, both analyzed using DSM-5 diagnosis (present vs absent) as the gold standard. ROC curve plotted for GDS-27 revealed an AUC of 0.846 (95% CI = 0.776 - 0.917, p < .001). The analysis of sensitivity and specificity values and corresponding Youden Index values, displayed in Table 5, showed an optimal cut-off for depression screening of 15/16 (absent/present), resulting in a sensitivity of 100% (95% CI = 0.80 - 1.00) and specificity of 63% (95% CI = 0.52 – 0.72). Positive and negative predictive values for cut-off of 15/16 were 0.36 (95% CI = 0.24 - 0.50) and 1.00 (95% CI = 0.93 - 1.00), respectively.

For GDS-15, ROC curve analysis resulted in an AUC of 0.821 (95% CI = 0.739 – 0.904, p < .001). In this case, the optimal cut-off value for depression screening was of 8/9 (absent/present), resulting in a sensitivity of 90% (95% CI = 0.67 - 0.98) and specificity of 62% (95% CI = 0.51 – 0.71). Positive and negative predictive values for cut-off of 8/9 were 0.33 (95% CI = 0.21 - 0.47) and 0.97 (95% CI = 0.88 - 0.99), respectively.

3.4.4. Depressive symptomatology and MMSE score

To analyze the potential effect of the covariates of MMSE score on the performance of the GDS-27 and GDS-15, a non-parametric ANCOVA was performed using mean ranks of both the dependent variable and covariate. The F statistic was calculated using the univariate ANOVA of non-standardized residuals obtained through linear regression of the rank of the dependent variable on the rank of the covariate. The F-test showed that the different scores obtained by depressed and non-depressed older adults in both questionnaires cannot be explained by MMSE score distribution (GDS-27: F = 30.258, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.208; GDS-15: F = 25.278, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.180).

4. Discussion

This study aimed to analyze the psychometric properties and screening performance of two Portuguese translated versions of the commonly used Geriatric Depression scale (GDS-27 and GDS-15) in mild-to-moderately cognitively impaired older adults. The mean GDS-27 and GDS-15 scores obtained in this sample were just over 14 and 7, respectively. As expected, depressive symptoms were significantly worse for those participants who met DSM-V criteria for depression.

Notably, reliability analyses revealed strong internal consistency reliability in both versions of this scale (GDS-27: α = 0.874; GDS-15: α = 0.812). This results are consistent with the internal consistency found for the general Portuguese population (GDS-27: α = 0.91; GDS-15: α = 0.83) in previous studies by Pocinho et al. (2009) and Apóstolo et al. (2014). While overall internal consistency was strong, there were some items on the scale that were notably weaker than others, which raises questions about the functions of those items within our sample. For example, the lowest item correlation on the GDS-15 asks about the patient worrying about bad things happening (item 6) and second lowest correlation asks about one’s preference to staying home versus going out and doing things (item 9). Responses to these two items in our sample, who are majority residents in a supervised institutional setting (76%), may reflect life circumstances and may be sample specific. That is, our sample is mostly comprised of individuals living in a supervised residential setting, which inherently has reduced autonomy and independence that may be reflected in that item (and thus reduced variability of the item) rather than the effects of depressed mood specifically. Similar findings on the GDS-27 also were observed with the lowest correlation the item asking also asks about preferring to stay at home rather than doing things (item 12) and being preoccupied about the past (item 18).

Furthermore, the scale had good validity. We explored convergent validity by examining associations between both the GDS-15 and GDS-27 and a gold standard measure for self-reported depression, the BDI-II, and found strong associations. These results are consistent with previous exploration of the validity of the Portuguese GDS-30 (Pocinho et al. (2009) and GDS-15 (Apóstolo et al. (2014, 2018a) in our cognitively impaired sample. Furthermore, when grouping the BDI-II items by items aligned with cognitive-affective and somatic subscales, the two GDS versions continued to demonstrate strong associations.

Since both the GDS-27 and the GDS-15 obtained good reliability and validity, clinicians can opt for using the GDS-15 to avoid fatigue in the population of people with cognitive impairment.

Another important indicator of a strong measure is sensitivity to identifying the underlying construct. The two GDS versions had strong sensitivity at identifying those with diagnosed clinical depression, being useful as screening tool. In particular, while this relatively brief self-report form was not strongly able to identify nuances of depression, we were able to identify those with and without diagnosed depression with high accuracy on both the GDS-15 and GDS-27. Along these lines, we were able to identify ideal cutoff scores on the GDS scales that provide ideal levels of sensitivity and specificity. Specifically, we found scores of 8/9 on the GDS-15 and 15/16 on the GDS-27 as optimal cutoff points in the screening identification of depression. Thus, we feel confident in the ability of this tool to serve as a good screening measure that can help identify when patients need follow up for mood evaluation and treatment.

Notably, our ideal cutoff scores are higher than typical cutoff points in other Portuguese speaking populations, which fall at 4/5 on the GDS-15 (Almeida & Almeida, 1999; Apostolo et al., 2018) It is possible that our cognitively impaired sample endorsed more of the cognitively oriented symptoms (e.g., more memory problems than most; worry about bad things happening) than a cognitively intact older adult population, instead capturing the effects of cognitive deficits rather than being mood-related in nature. Nonetheless, these cutoff values are still well-within ranges found in other studies. Cutoffs have been reported as high as 7/8 in other translated versions of the GDS-15 (Malakouti et al., 2006), and 10/11 on the GDS-30 (Adams et al., 2004). Further, on the GDS-30, it has ranged up to 16 in other clinical samples and translations (Bologna et al., 2019). Further, while our analyses revealed high sensitivity rates (90-100%) our specificity rates were lower than statistically ideal (62-63%), though this also is within the specificity range found in past reviews of the GDS-15 and GDS-30 (Wancata, 2006) and thus consistent with the general performance of the scale. Thus, our overall scores revealed sensitivity and specificity consistent with the GDS performance in other studies, and in our sample GDS scores remained consistent across demographic characteristic, including gender and education, and importantly and arguing for good consistency of the measure. Overall, we were able to demonstrate sound discriminability of the GDS in those in our sample with and without depression.

Naturally, this study has some limitations. First, our use of a convenience sample has implications for the generalizability of the study findings to a wider population. To reduce the impact of this limitation, the recruitment process was carried out in different settings and different geographical locations, involving both institutionalized and community-dwelling older adults. Second, we used a relatively small sample size for a psychometric exploration. Namely, although a large number of older adults were contacted, the study sample included only 117 participants. This reduced adherence reflects the difficulties that health professionals often face in recruiting older adults with neurocognitive disorders to research projects. It should also be noted that of all participants included in the study, only 20 met DSM-5 criteria for major depressive episode. Another limitation of the study was the non-use of a diagnostic tool, rather than a screening one, to complement the diagnosis of a neurocognitive disorder according to DSM-5. Finally, because we did not control or restrict access to antidepressant medications, the present study did not evaluate whether the results obtained in the GDS were affected or not by antidepressant medication taken by participants. In further studies, this potential effect of medication intake should be examined in a controlled manner.

5. Conclusion

A better understanding the psychometrics of any measure helps improve clinicians and researchers’ confidence in the validity and reliability of the measure when administering this scale in their practice. This study provides support for the psychometric properties of the GDS-15 and GDS-27 in a sample of mild-to-moderate cognitively impairment persons. Our results support that both GDS-27 and GDS-15 are reliable and valid instruments for assessing for depressive symptoms and screening for depression in Portuguese persons with cognitive impairment. This knowledge adds to a growing body of literature exploring the psychometrics of the GDS in various settings globally and specifically, contributes to the growing knowledge of the Portuguese versions of the GDS-15 and GDS-27.

Acknowledgments

The research sites and the evaluators involved were: Assoc. de Desenvolvimento da Vila de Paço Sousa (Ana Nunes); Assoc. de Solidariedade Social de Ponte de Sôr (Carina Veludo); Cáritas de Coimbra (Vera Cavaco); Cbesa (Ana Sofia Gomes); Cediara (Ana Elisa Castro); Centro de Assistência Paroquial da Pampilhosa (Joana Ribeiro); Centro Social de Oiã (Fátima Alves); Centro Social e Paroquial de Alcabideche (Filipa Couceiro); Centro Social e Paroquial de S. Martinho de Medelo (Patrícia Rodrigues, Sandrina Ribeiro); Centro Social Paroquial de Recarei (Ana Soraia Mendes); Centro Social Vale do Homem (Sandrine Vale); Fundação Afid Diferença (Teresa Reis); Fundação João Bento Raimundo (Mónica Garcia); Fundação Luiz Bernardo de Almeida (Laura Beatriz); Fundação Sarah Beirão/António Costa Carvalho (Ana Sofia Cavaleiro); Irmãs Hospitaleiras (Cátia Gameiro); Lar D. Pedro V (Salomé Vasconcelos); Lar de São José (Andreia Sousa); Misericórdia de Alcobaça (Ivone António); Misericórdia de Alvorge (Sílvia Lopes); Misericórdia de Arez (Eduardo Raimundo); Misericórdia de Arronches (Vanda Pinto); Misericórdia de Caminha (Margarida Capela); Misericórdia de Canha (Marlene Pedreirinho); Misericórdia de Castelo Branco (Sofia Fernandes); Misericórdia de Ferreira do Alentejo (Raquel do Pereiro); Misericórdia de Melgaço (Manuela Lobato); Misericórdia de Tarouca (Vanessa Ferreira); Misericórdia de Vouzela (Rui Dionísio); Misericórdia do Fundão (Sara Alvarinha); Prodeco (Beatriz Ferreira); Quintinha da Conceição Sousa (Ana Sofia Mendes); Replicar Socialform (Rui Maia). Technical and scientific support: Alzheimer Portugal; CREA - Centro de Referencia Estatal de Atención a Personas con Enfermedad de Alzheimer y otras Demencias del Imserso en Salamanca. Ethics committee: Unidade Investigação em Ciências da Saúde: Enfermagem (UICISA: E) da Escola Superior de Enfermagem de Coimbra.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Adams, K.B.; Matto, H.C.; Sanders, S. Confirmatory factor analysis of the geriatric depression scale. Gerontologist 2004, 44, 818–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E Allan, C.; Valkanova, V.; Ebmeier, K.P. Depression in older people is underdiagnosed. Practitioner 2014, 258, 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, O. P.; Almeida, S. A. Short versions of the Geriatric Depression Scale: A study of their validity for the diagnosis of a major depressive episode according to ICD-10 and DSM-IV. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 1999, 14, 858–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), construct: Depressive symptoms, 2020. Available online: https://www.apa.org/pi/about/publications/caregivers/practice-settings/assessment/tools/geriatric-depression.

- Apóstolo, J.L.A.; Bobrowicz-Campos, E.M.; dos Reis, I.A.C.; Henriques, S.J.; Correia, C.A.V. Exploring a capacity to screen of the European Portuguese version of the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale. Revista de Psicopatología y Psicología Clínica 2018, 23, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apóstolo, J.; Bobrowicz-Campos, E.; Reis, I.; Henriques, S.; Correia, C. Screening capacity of Geriatric Depression Scale with 10 and 5 items. Revista de Enfermagem Referência 2018, 4, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apóstolo, J.; Loureiro, L.; Reis, I.; Silva, I.; Cardoso, D.; Sfetcu, R. Contribution to the adaptation of the Geriatric Depression Scale -15 into portuguese. Revista de Enfermagem Referência 2014, IV, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Ball, R.; Ranieri, W.F. Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories-IA and-II in Psychiatric Outpatients. J. Pers. Assess. 1996, 67, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Ward, C.H.; Mendelson, M.; Mock, J.; Erbaugh, J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1961, 4, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bologna, M.; Merola, A.; Ricciardi, L. Behavioral and Emotional Dysfunction in Parkinson’s Disease. Park. Dis. 2019, 2019, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, R.C.; Gonçalves, B. The Portuguese Version of the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II). Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2011, 27, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd ed.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Debruyne, H.; Van Buggenhout, M.; Le Bastard, N.; Aries, M.; Audenaert, K.; De Deyn, P.P.; Engelborghs, S. Is the geriatric depression scale a reliable screening tool for depressive symptoms in elderly patients with cognitive impairment? Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2009, 24, 556–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drago, S.; Martins, R. A depressão no idoso [Depression in the elderly]. Millenium 2012, 43, 79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Durmaz, B.; Soysal, P.; Ellidokuz, H.; Is, A.T. Validity and Reliability of Geriatric Depression Scale - 15 (Short Form) in Turkish older adults. North. Clin. Istanb. 2017, 5, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferenchick, E.K.; Ramanuj, P.; Pincus, H.A. Depression in primary care: part 1—screening and diagnosis. BMJ 2019, 365, l794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- First, M. B.; Williams, J. B. W.; Karg, R. S.; Spitzer, R. L. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Disorders, Clinician Version (SCID-5-CV); American Psychiatric Association, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fluss, R.; Faraggi, D.; Reiser, B. Estimation of the Youden Index and its Associated Cutoff Point. Biom. J. 2005, 47, 458–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. “Mini-Mental State”. A Practical Method for Grading the Cognitive State of Patients for the Clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galeoto, G.; Sansoni, J.; Scuccimarri, M.; Bruni, V.; De Santis, R.; Colucci, M.; Valente, D.; Tofani, M. A Psychometric Properties Evaluation of the Italian Version of the Geriatric Depression Scale. Depression Res. Treat. 2018, 2018, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerreiro, M.; Silva, A. P.; Botelho, M. A.; Leitão, O.; Castro-Caldas, A.; Garcia, C. Adaptação à população portuguesa da tradução do "Mini Mental State Examination" (MMSE) [Adaptation to the Portuguese population of the translated "Mini Mental State Examination" (MMSE)]. Revista Portuguesa de Neurologia 1994, 1, 9–10. [Google Scholar]

- Havins, W.N.; Massman, P.J.; Doody, R. Factor Structure of the Geriatric Depression Scale and Relationships with Cognition and Function in Alzheimer’s Disease. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2012, 34, 360–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jefferson, A.L.; Powers, D.V.; Pope, M. Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) and the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) in Older Women. Clin. Gerontol. 2001, 22, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamoorthy, Y.; Rajaa, S.; Rehman, T. Diagnostic accuracy of various forms of geriatric depression scale for screening of depression among older adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2019, 87, 104002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lach, H.W.; Chang, Y.-P.; Edwards, D. Can Older Adults with Dementia ACCURATELY Report Depression Using Brief Forms?: Reliability and Validity of the Geriatric Depression Scale. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2010, 36, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Jeon, Y.-H.; Low, L.-F.; Chenoweth, L.; O’connor, D.W.; Beattie, E.; Brodaty, H. Validity of the geriatric depression scale and the collateral source version of the geriatric depression scale in nursing homes. Int. Psychogeriatrics 2015, 27, 1495–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marôco, J. Análise Estatística com o SPSS Statistics [Statistical Analysis with SPSS Statistics] (5th ed.). Report Number – Análise e Gestão de Informação, Lda. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, A.J.; Bird, V.; Rizzo, M.; Meader, N. Diagnostic validity and added value of the geriatric depression scale for depression in primary care: A meta-analysis of GDS30 and GDS15. J. Affect. Disord. 2010, 125, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgado, J.; Rocha, C. S.; Maruta, C.; Guerreiro, M.; Martins, I. P. Novos valores normativos do Mini-Mental State Examination [New normative values of Mini-Mental State Examination]. Sinapse 2009, 2, 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki, Y.; Sposito, A. P. B.; Bueno, D. R. S.; Guariento, M. E. Depression and chronic diseases in the elderly. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Clínica Médica 2015, 13, 149–153. [Google Scholar]

- Pocinho, M.T.S.; Farate, C.; Dias, C.A.; Lee, T.T.; Yesavage, J.A. Clinical and Psychometric Validation of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) for Portuguese Elders. Clin. Gerontol. 2009, 32, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocklington, C.; Gilbody, S.; Manea, L.; McMillan, D. The diagnostic accuracy of brief versions of the Geriatric Depression Scale: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2016, 31, 837–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segal, D.L.; Coolidge, F.L.; Cahill, B.S.; O'Riley, A.A. Psychometric Properties of the Beck Depression Inventory—II (BDI-II) Among Community-Dwelling Older Adults. Behav. Modif. 2008, 32, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesavage, J.A.; Sheikh, J.I. 9/Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): Recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin. Gerontol. J. Aging Ment. Health 1986, 5, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, R.L.; de Medeiros, J.G.M.; de Moura, A.C.L.; Souza, C.L.e.M.d.; Moreira, I.F. Validade e fidedignidade da Escala de Depressão Geriátrica na identificação de idosos deprimidos em um hospital geral [Validity and reliability of the geriatric depression scale for the identification of depressed patients in a general hospital]. J. Bras. de Psiquiatr. 2007, 56, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics National Institute. Portal de Estatísticas Oficiais [Official Statistics Portal]. 2011. Available online: http://www.ine.pt/.

- A Steer, R.; Rissmiller, D.J.; Beck, A.T. Use of the Beck Depression Inventory-II with depressed geriatric inpatients. Behav. Res. Ther. 1999, 38, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugishita, K.; Sugishita, M.; Hemmi, I.; Asada, T.; Tanigawa, T. A Validity and Reliability Study of the Japanese Version of the Geriatric Depression Scale 15 (GDS-15-J). Clin. Gerontol. 2016, 40, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wancata, J.; Alexandrowicz, R.; Marquart, B.; Weiss, M.; Friedrich, F. The criterion validity of the Geriatric Depression Scale: a systematic review. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2006, 114, 398–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weeks, S.K.; McGann, P.E.; Michaels, T.K.; Penninx, B.W. Comparing Various Short-Form Geriatric Depression Scales Leads to the GDS-5/15. J. Nurs. Sch. 2003, 35, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization: Ageing and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- World Health Organization. Depression. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/depression#tab=tab_1.

- Yesavage, J.A.; Brink, T.L.; Rose, T.L.; Lum, O.; Huang, V.; Adey, M.; Leirer, V.O. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1983, 17, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

ROC curve for GDS-27, using DSM-5 diagnostic criteria as a gold standard.

Figure 2.

ROC curve for GDS-15, using DSM-5 diagnostic criteria as a gold standard.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic, clinical, and neuropsychological characteristics of study participants.

| Sociodemographic, clinical, and neuropsychological characteristics | Total sample (n = 117) |

Participants with depression (n = 20) | Participants without depression (n = 97) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (number): male/female | 27/90 | 3/17 | 24/73 |

| Age (years): mean ± SD (range) | 83.66 ± 7.47 (65-101) | 83.75 ± 7.92 (69-101) | 83.64 ± 7.42 (65-97) |

|

Education level (%): - up to 2 years - between 3 to 6 years - 7 years or more |

35.1% 58.1% 6.8% |

55.0% 45.0% ----- |

30.9% 60.8% 8.2% |

|

Marital status (%): - with partner - without partner |

17.1% 82.9% |

10.0% 90.0% |

18.6% 81.4% |

|

Type of institution attended (%) - residential structure / nursing home - adult day center - home support services - social center - other |

76.1% 11.1% 2.6% 2.6% 7.7% |

75.0% 20.0% ----- 5.0% ----- |

76.3% 9.3% 3.1% 2.1% 9.3% |

|

Type of neurocognitive disorder diagnosis - Vascular Neurocognitive Disorder - Neurocognitive Disorder due to Alzheimer Disease - Neurocognitive Disorder due to Parkinson Disease - Unspecified Neurocognitive Disorder - Neurocognitive Disorder due to traumatic brain injury - other (substance/medication induced or due to another medical condition) |

24.8% 23.9% 6.8% 36.8% 4.3% 3.4% |

15.0% 25.0% 10.0% 45.0% ----- 5.0% |

26.8% 23.7% 6.2% 35.0% 5.2% 3.1% |

|

Cognitive status MMSE (score): mean ± SD (range) |

18.89 ± 3.73 (9-27) |

19.15 ± 2.96 (13-24) |

18.84 ± 3.88 (9-27) |

Abbreviations: BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; DSM-5: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition; GDS: Geriatric Depression Scale; MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination.

Table 2.

Item and item-total statistics of Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) with 27 items.

| GDS-27 | Item mean (standard deviation) | Item-total correlation | Corrected item-total correlation | Alpha if item deleted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item 1 | 0.47 (0.50) | 0.629 | 0.575 | 0.866 |

| Item 2 | 0.76 (0.43) | 0.503 | 0.463 | 0.869 |

| Item 3 | 0.73 (0.44) | 0.678 | 0.634 | 0.865 |

| Item 4 | 0.64 (0.48) | 0.766 | 0.741 | 0.861 |

| Item 5 | 0.52 (0.50) | 0.496 | 0.450 | 0.869 |

| Item 6 | 0.47 (0.50) | 0.517 | 0.468 | 0.869 |

| Item 7 | 0.44 (0.50) | 0.557 | 0.521 | 0.867 |

| Item 8 | 0.50 (0.50) | 0.415 | 0.365 | 0.871 |

| Item 9 | 0.53 (0.50) | 0.555 | 0.507 | 0.867 |

| Item 10 | 0.49 (0.50) | 0.610 | 0.565 | 0.866 |

| Item 11 | 0.65 (0.48) | 0.521 | 0.464 | 0.869 |

| Item 12 | 0.50 (0.50) | 0.206 | 0.132 | 0.877 |

| Item 13 | 0.60 (0.49) | 0.411 | 0.332 | 0.872 |

| Item 14 | 0.31 (0.46) | 0.300 | 0.263 | 0.874 |

| Item 15 | 0.27 (0.44) | 0.354 | 0.298 | 0.873 |

| Item 16 | 0.68 (0.47) | 0.733 | 0.700 | 0.863 |

| Item 17 | 0.80 (0.40) | 0.571 | 0.537 | 0.867 |

| Item 18 | 0.36 (0.48) | 0.274 | 0.186 | 0.876 |

| Item 19 | 0.46 (0.50) | 0.405 | 0.338 | 0.872 |

| Item 20 | 0.61 (0.49) | 0.449 | 0.379 | 0.871 |

| Item 21 | 0.59 (0.50) | 0.394 | 0.340 | 0.872 |

| Item 22 | 0.52 (0.50) | 0.310 | 0.225 | 0.875 |

| Item 23 | 0.52 (0.50) | 0.506 | 0.443 | 0.869 |

| Item 24 | 0.62 (0.49) | 0.445 | 0.375 | 0.871 |

| Item 25 | 0.64 (0.48) | 0.552 | 0.474 | 0.868 |

| Item 26 | 0.60 (0.49) | 0.487 | 0.424 | 0.870 |

| Item 28 | 0.50 (0.50) | 0.371 | 0.290 | 0.873 |

Table 3.

Item and item-total statistics of Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) with 15 items.

| GDS-15 | Item mean (standard deviation) | Item-total correlation | Corrected item-total correlation | Alpha if item deleted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item 1 | 0.45 (0.50) | 0.710 | 0.642 | 0.785 |

| Item 2 | 0.74 (0.44) | 0.525 | 0.424 | 0.801 |

| Item 3 | 0.77 (0.43) | 0.596 | 0.527 | 0.795 |

| Item 4 | 0.63 (0.49) | 0.717 | 0.652 | 0.784 |

| Item 5 | 0.40 (0.49) | 0.636 | 0.557 | 0.791 |

| Item 6 | 0.50 (0.50) | 0.371 | 0.262 | 0.813 |

| Item 7 | 0.53 (0.50) | 0.680 | 0.607 | 0.787 |

| Item 8 | 0.40 (0.49) | 0.606 | 0.490 | 0.796 |

| Item 9 | 0.46 (0.50) | 0.267 | 0.135 | 0.822 |

| Item 10 | 0.36 (0.48) | 0.395 | 0.294 | 0.810 |

| Item 11 | 0.21 (0.41) | 0.396 | 0.325 | 0.807 |

| Item 12 | 0.72 (0.45) | 0.602 | 0.521 | 0.795 |

| Item 13 | 0.69 (0.46) | 0.444 | 0.350 | 0.806 |

| Item 14 | 0.54 (0.50) | 0.414 | 0.308 | 0.810 |

| Item 15 | 0.55 (0.50) | 0.427 | 0.322 | 0.809 |

Table 4.

Results on the GDS questionnaires for the subsample of depressed and non-depressed participants.

Table 4.

Results on the GDS questionnaires for the subsample of depressed and non-depressed participants.

| DSM-5 diagnostic criteria | Mean ± SD (range) | |

|---|---|---|

| GDS-15 | GDS-27 | |

| with depression (n=20) | 11.05 ± 2.01 (7-14) | 20.45 ± 2.89 (16-25) |

| - mild depression (n=10) | 10.40 ± 1.43 (9-13) | 19.70 ± 3.09 (16-25) |

| - moderate depression (n=7) | 11.00 ± 2.52 (7-13) | 20.43 ± 2.64 (16-24) |

| - severe depression (n=3) | 13.33 ± 0.58 (13-14) | 23.00 ± 1.73 (21-24) |

| without depression (n=97) | 6.99 ± 3.65 (0-15) | 12.80 ± 6.50 (1-27) |

Abbreviations: DSM-5: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition; GDS: Geriatric Depression Scale.

Table 5.

Sensitivity, specificity, and Youden Index of Geriatric Depression Scale with 27 and 15.

| GDS-27 | GDS-15 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cut-off point | Sensitivity | Specificity | Youden Index | Cut-off point | Sensitivity | Specificity | Youden Index |

| 1.50 | 100% | 3% | 0.031 | 0.50 | 100% | 1% | 0.01 |

| 2.50 | 100% | 4% | 0.041 | 1.50 | 100% | 5% | 0.05 |

| 3.50 | 100% | 5% | 0.052 | 2.50 | 100% | 14% | 0.14 |

| 4.50 | 100% | 13% | 0.134 | 3.50 | 100% | 23% | 0.23 |

| 5.50 | 100% | 20% | 0.196 | 4.50 | 100% | 29% | 0.29 |

| 6.50 | 100% | 22% | 0.216 | 5.50 | 100% | 39% | 0.39 |

| 7.50 | 100% | 24% | 0.237 | 6.50 | 100% | 43% | 0.43 |

| 8.50 | 100% | 29% | 0.289 | 7.50 | 95% | 52% | 0.47 |

| 9.50 | 100% | 35% | 0.351 | 8.50 | 90% | 62% | 0.52 |

| 10.50 | 100% | 40% | 0.402 | 9.50 | 75% | 73% | 0.48 |

| 11.50 | 100% | 42% | 0.423 | 10.50 | 55% | 81% | 0.36 |

| 12.50 | 100% | 45% | 0.454 | 11.50 | 50% | 90% | 0.40 |

| 13.50 | 100% | 51% | 0.505 | 12.50 | 35% | 93% | 0.28 |

| 14.50 | 100% | 59% | 0.588 | 13.50 | 5% | 97% | 0.02 |

| 15.50 | 100% | 63% | 0.629 | 14.50 | 0% | 99% | -0.01 |

| 16.50 | 90% | 68% | 0.580 | ||||

| 17.50 | 80% | 75% | 0.553 | ||||

| 18.50 | 70% | 79% | 0.494 | ||||

| 19.50 | 60% | 85% | 0.445 | ||||

| 20.50 | 50% | 86% | 0.356 | ||||

| 21.50 | 40% | 88% | 0.276 | ||||

| 22.50 | 25% | 93% | 0.178 | ||||

| 23.50 | 25% | 96% | 0.209 | ||||

| 24.50 | 5% | 98% | 0.029 | ||||

| 26.00 | 0% | 99% | -0.010 | ||||

items: In bold: values of cut-off point, sensitivity, and specificity for the maximal Youden Index.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Copyright: This open access article is published under a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license, which permit the free download, distribution, and reuse, provided that the author and preprint are cited in any reuse.

Psychometric Properties and Screening Performance of the Geriatric Depression Scale in a Mild-to-Moderate Cognitively Impaired Portuguese Sample

Susana Isabel Justo-Henriques

et al.

,

2023

Comparison of the 10-, 14- and 20-Item CES-D Scores as Predictors of Cognitive Decline

Ainara Jauregi Zinkunegi

et al.

,

2023

Neurocognitive Changes in Patients with Post-COVID Depression

Marina Khodanovich

et al.

,

2023

MDPI Initiatives

Important Links

© 2024 MDPI (Basel, Switzerland) unless otherwise stated