Preprint

Article

Clinical Features and Outcomes of Association of Co-infections in Children with LaboratoryConfirmed Influenza, during 2022–2023 Season; a Romanian Perspective

Altmetrics

Downloads

96

Views

28

Comments

0

A peer-reviewed article of this preprint also exists.

This version is not peer-reviewed

Submitted:

29 August 2023

Posted:

04 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Alerts

Abstract

The 2022-2023 influenza season in Romania was characterized by high pediatric hospitalization rates, predominated by influenza A subtypes H1N1 and H3N2. Lowered population immunity to influenza after the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and subsequent stoppage of influenza circulation, particularly in children who had limited pre-pandemic exposures, influenced hospitalization among children immunosuppressed, and patients with concurrent medical conditions who are at increased risk for developing severe forms of influenza. This study focused on the characteristics of influenza issues among paediatric patients, as well as the relationship between different influenza virus types and viral and bacterial coinfections and illness severity in the 2022-2023 season after the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. We conducted a retrospective clinical analysis on 301 cases of influenza in pediatric inpatients (age ≤ 18 years), hospitalized at the National Institute of Infectious Diseases "Prof. Dr. Matei Balș" IX Pediatric Infectious Diseases Clinical Section between October 2022 and February 2023. The most significant age group was 57.8% representing children between one to four years old and female. The average clinical forms were found in 61.7%, whereas severe versions represented 18.2% of cases. Most of the complications were respiratory (acute interstitial pneumonia, 76.1%), hematological (72.1%), represented by intra-infectious and deficiency anemia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia), 33.6% were digestive, such as diarrheal disease, liver cytolysis syndrome, and the acute dehydration syndrome associated with electrolyte imbalance (71.4%). Severe complications were associated with a risk of unfavorable evolution: acute respiratory failure and neurological complications (convulsions, encephalitis). No deaths were reported. We noticed that the flu season 2022-2023 was characterized by the association of co-infections (viral, bacterial, fungal and parasitic) more frequent than in previous years (26.2% vs. 16%), which evolved more severely, with prolonged hospitalization and more complications (p<0.05), and time of use of oxygen therapy was statistically significant (p > 0.05); influenza vaccination in this group was zero. In conclusion, coinfections with respiratory viruses increase the severity of the pediatric population's immunity to influenza, especially among young children who are more vulnerable to developing a serious illness. All people above the age of six months should get vaccinated against influenza to prevent the illness and its severe complications.

Keywords:

Subject: Medicine and Pharmacology - Pediatrics, Perinatology and Child Health

Introduction

After the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in December 2019, there were notable falls in influenza activity throughout the world. [1,2,3]. Numerous research has demonstrated that the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of respiratory illnesses have changed [4,5,6]. Influenza A and B viruses cause seasonal influenza in humans of all ages with a variety of severity levels. The risk of infection is highest in children, with annual incidence rates reaching up to 30%. Due to the high incidence of influenza-related hospitalizations among children aged 6 to 59 months, the World Health Organization identifies this age category as one of the risk groups for influenza and underlines the importance of prioritizing them for yearly influenza vaccine. Furthermore, because of their lack of past exposure and immunity to the virus, children are typically the principal transmitters of influenza in the community; they shed the virus at greater titres and for a longer length of time than adults do. [7,8,9,10,11,12,13].

When the severity of influenza is compared in children with different age groups, the clinical presentation, such as fever, malaise, cough, rhinitis, headache, etc., of the illness varies, and also the complications.[14,15,16,17]. Due to these factors, it is exceedingly challenging to differentiate between them clinically and to initiate efficient management based on modern medical treatment to reduce mortality and morbidity. [18,19,20,21].The relevance of these respiratory disorders and the clinical manifestation of viral co-infections are more likely found in children diagnosed with influenza A and B viruses who have more severe clinical symptoms and need hospitalization more frequently and for a long time. Children who have chronic diseases and other medical conditions are more likely to experience complications from influenza than healthy children. Several pulmonary and extrapulmonary problems, such as myocarditis and pericarditis, myositis or rhabdomyolysis, and seizures, might occur.[22,23,24,25,26].

In the EU countries including Romania, the influenza virus activity nearly reached pre-pandemic levels during the 2022–2023 influenza season. Compared to the four preceding seasons, this one was distinguished by an earlier start to the seasonal epidemic and an earlier peak in positivity. According to the Romanian National Center for Statistics, the influenza vaccine administration in the pediatric population decreased to 2.5% during the 2022–2023 season. Everyone over the age of six months in Romania is eligible for the influenza vaccination, but the Ministry of Health only offers it complementary to vulnerable populations like patients with coexisting conditions, HIV infection, pregnant women, people older than 65, institutionalized individuals, and social and medical professionals. [27,28].

In the present study, we aim to analyze the epidemiological particularities of influenza in children in the post-pandemic season of COVID-19 (type of circulating influenza virus, age groups and gender, of affected children, co-infections associated with influenza), in unvaccinated children. We will also identify the clinical forms of the disease, the complications and the evolution of influenza in children hospitalized between October 2022 and February 2023. The information gathered may be essential in predicting illness development, prognosis, and treatment plans, particularly in pediatric populations.

Methods

To achieve the proposed objectives, we conducted a clinical retrospective study of influenza laboratory-confirmed pediatric cases, hospitalized between October 2022 and February 2023 in the Clinical Section IX Pediatric Infectious Diseases of the National Institute of Infectious Diseases "Prof. Dr. Matei Balș", Bucharest, Romania. Data analyzed included the following parameters: age, sex, the type of influenza virus, the clinical form of the disease, the complications and the evolution of the flu. To date, influenza detections were higher for Influenza A H1N1 and H3N2, and the largest proportion of hospitalized cases among children was between the ages of 0-4 years old. We also analyzed the co-infections associated with the flu for children included in the study as well as their impact on the disease. Patients with at least one influenza diagnosis and a positive finding for the respiratory specimen (nasopharyngeal or pharyngeal swab) from laboratory tests were identified as having laboratory-confirmed influenza by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). The children included in this study were divided into groups after Influenza type and subtype were identified and studied clinical manifestations, and we compared children with complications during hospitalisation. A pathogenic microorganism that was isolated within 14 days of the beginning of influenza was considered a concurrent infection. In all the cases studied, the usual laboratory investigations (hemogram, biochemical tests, inflammatory tests) were performed as well as, depending on the complications, cultures (blood cultures, pharyngeal exudate, urine culture) and paraclinical investigations (cardio-pulmonary radiography). Any unfavourable clinical episode within 14 days of a diagnosis of influenza was considered an influenza-related complication and included respiratory, haematological and digestive, but also neurological. The study and the informed consent forms from all parents and legal guardians of patients included were approved by the Bioethics Committee of the National Institute for Infectious Diseases “Prof. Dr. Matei Balș”, Bucharest, Romania according to the Helsinki Declaration of 1964. The differences in means and medians for continuous variables are provided using the Student's t-test or the Kruskal–Wallis test. Categorical variables were analyzed univariately using Fisher's exact test. To determine the variables linked to complications, multivariable logistic regression was employed. Statistics were considered significant for p-values under 0.05(2-tailed test). All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad 9.1.1.

Results

During October 2022 and February 2023, a total number of 301 consecutive pediatric cases were hospitalized at the National Institute for Infectious Diseases “Prof. Dr. Matei Bals”, Bucharest, Romania, with laboratory-confirmed influenza A (244/301, 81.06%, H1N1-represents 66.4% and H3N2 =33.6%), influenza B (24/301, 7.97%), influenza A+B, (19/301, 6.31%), and not-subtyped influenza (14/301,4.65%). The median age was 4.7 years, [interquartile range (IQR) 2.8–12.2 years]. The proportion of girls was higher than that of boys. (58.14% vs. 41.86). All cases evolved favourably, without deaths throughout the study.

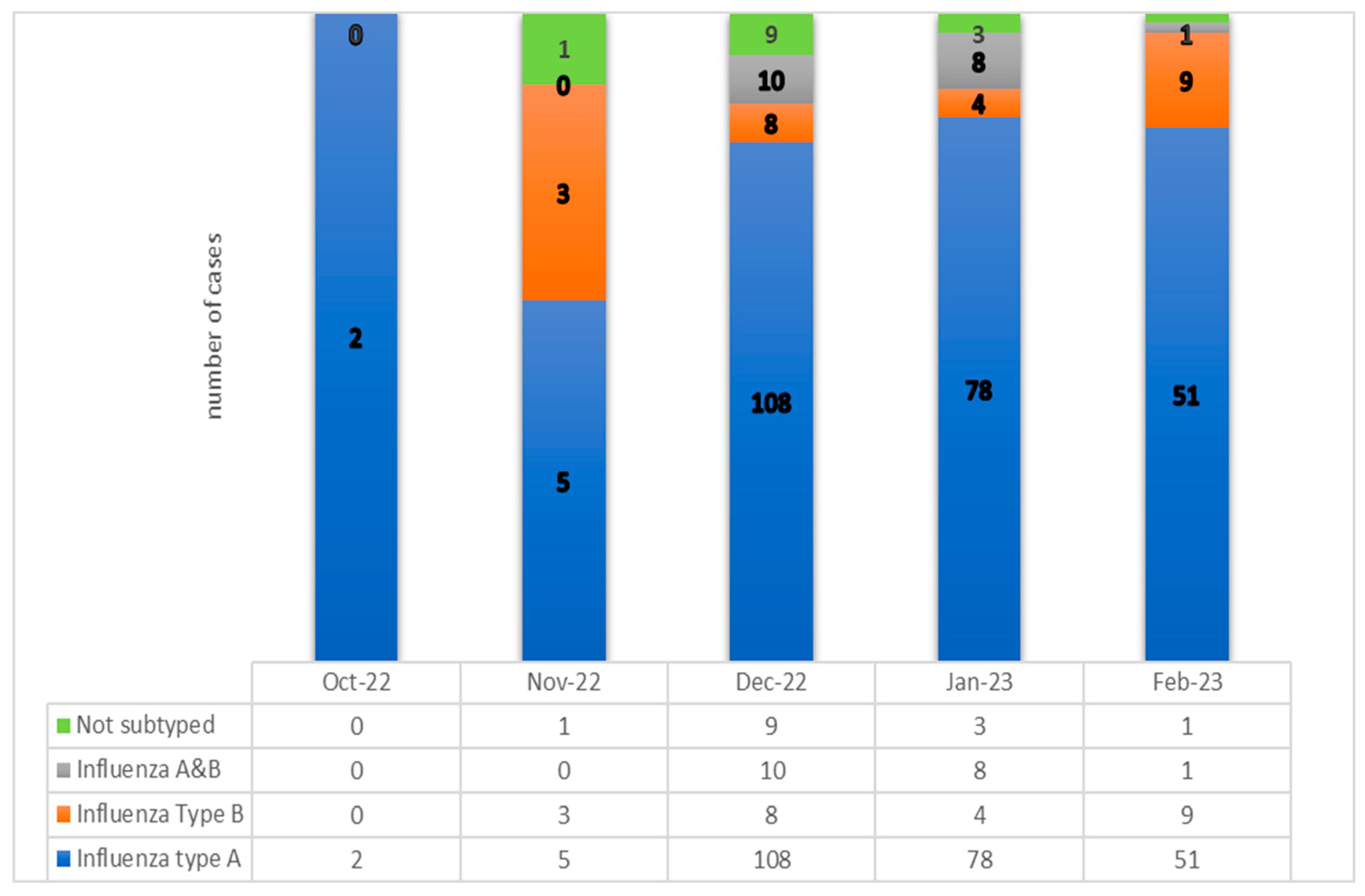

In this influenza season 2022-2023, we diagnosed a spread with a peak number of 108 pediatric cases for December 2022 (35.88%) and 78 for January 2023 (25.91%). (See Figure 1). In this study, influenza A viruses were the most dominant strain type during most seasons and caused 244 episodes which represented 81% of the total group. The proportion of children with influenza A, subtype H1N1 was 66,4 %, and 33,6 % were recorded for A/H3N2. (See Figure 1).

There were significant differences in the age distribution by Influenza subtype. The median age of children with influenza A and B infection was 3.338 and 6.228 years, respectively (p < 0.001). The median age of children with dual influenza A and B infection was lower than the other groups, 3.21 years old respectively, (p<0.05).

The demographics and clinical characteristics of the pediatric patients in the study group are shown in Table 1. Younger children were more likely to be symptomatically infected with influenza A than influenza B, with an average age of cases of 3.338 years for influenza A and 6.228 years for influenza B (p< 0.05). There were significant differences in the age distribution by subtype or coinfection Influenza A+B and for age groups. (See Table 1).

At presentation, patients with influenza A had higher admission temperature (median 38.5 °C, IQR [37.7–38.8]) vs. 37.6 (36.8–38.2]; p = 0.02) for Influenza B, and 100% of patients with Influenza A+B had high fever(>38.8˚C). Other baseline vital signs and clinical data were similar between the pediatric patient groups. In a comparison of the demographic characteristics and clinical outcomes, we found that severe forms stay was more frequently required for age under 1 year old for influenza A (2.4% vs. 0.62%, p < 0.001) than in patients with influenza B infection. All of the admitted infants younger than one year old were full-term births, they all have siblings, and medical history wasn't relevant.

There was a significant difference between the influenza subtypes in terms of the clinical symptoms and days of antiviral administrations. 80.06% received oseltamivir, The respiratory symptoms except rhinorrhea and cough were statistically significant. There were differences in clinical features between the A(H3N2) and A(H1N1) and between the B and A+B Influenza coinfection, in respiratory and digestive symptoms. Fever, cough and dyspnea were the three most common symptoms, with statistical differences between the two types of influenza, A and B, and between subtypes of Influenza A, and when we compared the Influenza A group with A+B coinfection. (See Table 1). More patients with influenza A reported respiratory symptoms, while Influenza A+B and Influenza B reported more frequent digestive manifestations, such as vomiting and diarrhea. For details, see Table 1.

The median number of days of hospitalisation was found statistically significant for comparison between Influenza A and A+B, and between A and B type. The longest median number of days of hospitalisations was found for coinfection A+B influenza (10 days). The mean length of hospital stay was 5.4 ± 5.5 days [4 - 14 days], with a median of 8 days for Influenza B. Oseltamivir therapy was begun for 80.07% of the entire group. At admission, 84.02% of patients with influenza A and 83.33% of cases with influenza B received oseltamivir. For A+B Influenza, we administrated oseltamivir for 84.21% of pediatric patients. Vomiting during oseltamivir administration was reported in 10 patients, and 24 patients reported diarrhoea, but the treatment was not discontinued because the patients evolved favourably.

Patients with Influenza A+B had a significantly longer length of hospital stay (10 days, [7,8,9,10,11], p=0.011). Although they had a longer administration of oseltamivir than other groups (7 days, IQR [7,8,9], p=0.05).

A significantly greater proportion of patients with moderate influenza were identified, and some of them were reported to have extra-pulmonary complications. Neurological and digestive manifestations of moderate influenza form were found in hospitalized pediatric patients and were significantly different between the moderate and severe groups. (See Table 2). Although significant differences in respiratory involvement were identified in patients diagnosed with pneumonia, bronchiolitis and laryngitis.

In 79 (26.2%) of hospitalized children's flu cases, we observed the association of other infections: bacterial (11.96%), viral (5.9%) and fungal (8.3%). (See Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison between the oseltamivir administration in the group with Influenza A vs. Influenza B, and for the group with A+B vs. Influenza A. ***P ≤ 0.001, **** P ≤ 0.0001, (χ2-tests).

Figure 2.

Comparison between the oseltamivir administration in the group with Influenza A vs. Influenza B, and for the group with A+B vs. Influenza A. ***P ≤ 0.001, **** P ≤ 0.0001, (χ2-tests).

Figure 2.

The number of cases of laboratory-confirmed bacterial, viral and fungal co-infections in pediatric cases diagnosed with Influenza, in 2022-2023 season, compared by clinical forms.

Figure 2.

The number of cases of laboratory-confirmed bacterial, viral and fungal co-infections in pediatric cases diagnosed with Influenza, in 2022-2023 season, compared by clinical forms.

59 patients, (19.6%) of the total group had co-infections. Bacterial and fungal coinfections were most common in severe forms of Influenza. Bacterial co-infections were reported for 23 patients, S.aureus as the most common (39.5%) followed by M.pneumoniae, (31%) H influenza (13.25%), and others. Fungal co-pathogens were reported for Aspergillus spp. (38%), Candida spp. (29%), Candida albicans (n=23.3%) and others (9.7%). Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) type A was found in 12 cases, 4 patients in the age group 0-1 years with severe form, and 8 cases in moderate form in the 2-3 years old age group. (p<0.05).

None of the patients received influenza vaccine within the previous year before admission to our Pediatric Department.

Discussion

Due to the abandoning of preventive techniques, we observe an increase in the frequency of flu in children after a time with a relatively low number of flu cases in our country. The clinical characteristics, treatment, co-infections and days of hospitalisations in pediatric patients with influenza A, B, and A+B during the 2022-2023 influenza season were examined in this study. According to the influenza virus type and subtype, clinical characteristics and outcomes demonstrate relevant changes. Among children between 0-1 years old, influenza A+B virus infection appeared to be more serious than influenza A or B virus infection. Influenza A+B has a low incidence but is associated with an increased risk of influenza complications. The prevalence of influenza complications was influenced by bacterial, fungal and viral coinfection, necessitating the use of advanced medication. Patients with Influenza B had atypical manifestations, which included more often digestive symptoms, and the age category was statistically significant for the 13-18 age group. Influenza A was described according to influenza A strains, and patients with H1N1 were shown to be younger than H3N2. This result is consistent with findings from past research that found young children and infants have an increased risk of being admitted to the hospital with influenza. We identified several possible independent risk factors: age group represented by 0-1 years old, and 13-18 years old, respiratory symptoms such as fever, cough and dyspnea, vomiting and myalgia. In a study of pediatric patients with confirmed influenza infection, 95% of patients reported fever, 77% reported coughing, headache 26% and myalgia 7% were mentioned less frequently. Abdominal pain, nausea, and diarrhea are gastrointestinal symptoms. [29].

Co-infections with RSV type A were most frequently involved in these cases, especially at younger ages. Therefore, in co-infection with RSV and influenza viruses, it is challenging to determine whether each virus directly contributes to the pathogenesis of complications in babies 0-2 years of age. Respiratory and neurological complications associated with influenza have been reported in numerous studies. We identified that children with neurological involvement were healthy children before the influenza event, and they did not experience consequences after the episode, even if half of them were 2-3 years old age group. [30,31].

In terms of incidence and severity, influenza continues to be a risk and can cause complications such as pneumonia, which is one of the most common side effects of influenza, or even severe diseases such as encephalitis in the pediatric population. The purpose of the influenza vaccine is to lessen the morbidity and hospitalisation days, death caused by this illness as well as its complications. And in this regard, it is crucial to consider the requirement for immunizing the population of healthy youngsters.[32,33].

As a limitation of our study, we were unable to identify a comparison group of patients with severe complex influenza who had received the vaccination since all of the children in our trial had not received the seasonal influenza vaccine. [34].

Immunization may protect against both mild and severe complex influenza, the important findings emphasize the value of vaccination, for children aged > 6 months, especially for children who have siblings, as we found the presence of older siblings as a risk factor for influenza-confirmed admission in the age group under 2 years old.

Conclusions

To reduce influenza-related hospital admissions among young children, immunization of children who are eligible for the influenza vaccine and who have a sibling during the influenza season should be strongly encouraged, because if influenza returns, it is unknown how the virus will continue to evolve.

Author Contributions

All authors have equally contributed. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by Bioethics Committee of the National Institute for Infectious Diseases “Prof. Dr. Matei Balș”.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Nair H, Brooks WA, Katz M, et al. Global burden of respiratory infections due to seasonal influenza in young children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2011; 378:1917–30. [CrossRef]

- Centrul National de Supraveghere si Control al Bolilor Transmisibile. Covid 19 Raport Săptămânal de Supraveghere, Date. Raportate până la Data 14.05.2023. Available online: https://www.cnscbt.ro/index.php/informari-saptamanale/gripa/3464-informare-infectii-respiratorii-08-05-2023-14-05-2023-s-19/file.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Seasonal influenza vaccines. Stockholm: ECDC. [Accessed 18/08/2023]. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/seasonal-influenza/prevention-and-control/seasonal-influenza-vaccines.

- Chow EJ, Doyle JD, Uyeki TM. Influenza virus-related critical illness: prevention, diagnosis, treatment. Crit Care 2019;23:01–11. [CrossRef]

- Principi N, Esposito S. Severe influenza in children: incidence and risk factors. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2016;14:961–8. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2022-2023 northern hemisphere influenza season. Geneva: WHO. [Accessed 3 Feb 2023]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/recommended-composition-of-influenza-virus-vaccines-for-use-in-the-2022-2023-northern-hemisphere-influenza-season.

- Castillo EM, Coyne CJ, Brennan JJ, Tomaszewski CA. Rates of co-infection with other respiratory pathogens in patients positive for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). J Am Coll Emerg Physic Open. (2020) 1:592–6. [CrossRef]

- J. Rello, A. Rodriguez, P. Ibanez, L. Socias, J. Cebrian, A. Marques, et al.Intensive care adult patients with severe respiratory failure caused by Influenza A (H1N1)v in Spain Crit Care, 13 (2009), p. R148.

- Ding Q, Lu P, Fan Y, Xia Y, Liu M. The clinical characteristics of pneumonia patients coinfected with 2019 novel coronavirus and influenza virus in Wuhan, China. J Med Virol. (2020) 92:1549–55. [CrossRef]

- G. Dominguez-Cherit, S.E. Lapinsky, A.E. Macias, R. Pinto, L. Espinosa-Perez, A. de la Torre, et al.Critically Ill patients with 2009 influenza A(H1N1) in MexicoJAMA, 302 (2009), pp. 1880-1887.

- A. Kumar, R. Zarychanski, R. Pinto, D.J. Cook, J. Marshall, J. Lacroix, et al.Critically ill patients with 2009 influenza A(H1N1) infection in Canada JAMA, 302 (2009), pp. 1872-1879.

- S.A. Sellers, R.S. Hagan, F.G. Hayden, W.A. Fischer 2nd The hidden burden of influenza: a review of the extra-pulmonary complications of influenza infection Influenza Other Respir Viruses, 11 (2017), pp. 372-393.

- Groves HE, Papenburg J, Mehta K, et al. The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on influenza-related hospitalization, intensive care admission and mortality in children in Canada: a population-based study. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2022;7:100132. [CrossRef]

- Short KR, Kasper J, van der Aa S, Andeweg AC, Zaaraoui-Boutahar F, Goeijenbier M, Richard M, Herold S, Becker C, Scott DP, Limpens RW, Koster AJ, Bárcena M, Fouchier RA, Kirkpatrick CJ, Kuiken T. 2016. Influenza virus damages the alveolar barrier by disrupting epithelial cell tight junctions. Eur Respir J 47:954–966. [CrossRef]

- Mondal P, Sinharoy A, Gope S. The influence of COVID-19 on influenza and respiratory syncytial virus activities. Infect Dis Rep. 2022;14:134–141. [CrossRef]

- Huang QS, Wood T, Jelley L, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 nonpharmaceutical interventions on influenza and other respiratory viral infections in New Zealand. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1001. [CrossRef]

- Daniela Pițigoi, Oana Săndulescu, Maria Dorina Crăciun, Gheorghiță Jugulete, Anca Streinu-Cercel, Angelica Vișan, Claudia Rîciu, Alexandru Rafila, Victoria Aramă, Monica Luminos & Adrian Streinu-Cercel - Measles in Romania – clinical and epidemiological characteristics of hospitalized measles cases during the first three years of the 2016-ongoing epidemic, Virulence 2020 Vol 11, No 1, 11:1, 686-694. [CrossRef]

- Uyeki TM, Wentworth DE, Jernigan DB. Influenza activity in the US during the 2020–2021 season. JAMA. 2021;325:2247–2248. [CrossRef]

- Feng L, Zhang T, Wang Q, et al. Impact of COVID-19 outbreaks and interventions on influenza in China and the United States. Nat Commun. 2021;12:3249. [CrossRef]

- Puzelli S, Di Martino A, Facchini M, et al; Italian Influenza Laboratory Network. Co-circulation of the two influenza B lineages during 13 consecutive influenza surveillance seasons in Italy, 2004–2017. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):990. [CrossRef]

- Maltezou HC, Kossyvakis A, Lytras T, et al. Circulation of influenza type B lineages in Greece during 2005–2015 and estimation of their impact. Viral Immunol. 2020;33:94–98. [CrossRef]

- Yan Y, Ou J, Zhao S, et al. Characterization of influenza A and B viruses circulating in southern China during the 2017–2018 season. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:1079. [CrossRef]

- Wang L, Yang S, Yan X, Liu T, Feng Z, Li G. Comparing the yield of oropharyngeal swabs and sputum for detection of 11 common pathogens in hospitalized children with lower respiratory tract infection. Virol J. 2019;16:84. [CrossRef]

- Bhat, YR. Influenza B infections in children: a review. World J Clin Pediatr. 2020;9:44–52. [CrossRef]

- Gheorghita Jugulete, Daniela Pacurar, Mirela Luminita Pavelescu, Mihaela Safta, Elena Gheorghe, Bianca Borcos, Carmen Pavelescu, Mihaela Oros, Madalina Merisescu - Clinical and evolutionary features of SARS CoV-2 infection (COVID-19) in children, a Romanian perspective, MDPI – Children, 2022, 9, 1282. https://www.mdpi.com/journal/children. [CrossRef]

- Shen K, Yang Y. Expert consensus on diagnosis and treatment of influenza in children (2020 edition). Chin J Appl Clin Pediatr. 2020;35:1281–1288.

- Victor Daniel Miron, Oana Sandulescu, Constanta Angelica Visan, Maria Madalina Merisescu, Anca Streinu Cercel, Daniela Pitigoi, Alexandru Rafila, Olga Mihaela Dorobat, Gheorghiță Jugulete, Adrian Streinu Cercel, Silvia Stoicescu, Monica Luminita Luminos - Pneumococcal Colonization and Pneumococcal Disease in Children with Influenza Clinical, Laboratory and Epidemiological features, REV CHIM-BUCHAREST, Vol. 69, Nr. 10, October 2018, pag. 2749-53, www.revistadechimie.ro.

- Gheorghiță Jugulete, Mădălina Maria Merișescu, Alexandra Eugenia Bastian, Sabina Zurac, Monica Luminița Luminos - Severe form of A1H1 influenza in a child - case presentation, Rom J Leg Med, 387-391 [2019] DOI: 10.4323/rjlm.2018.387 © 2018 Romanian Society of Legal Medicine, www.rjml.ro. [CrossRef]

- Kamidani S, Garg S, Rolfes MA, et al. Epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and outcomes of influenza-associated hospitalizations in U.S. children over 9 seasons following the 2009 H1N1 pandemic [published online ahead of print April 19, 2022]. Clin Infect Dis. [CrossRef]

- Frankl S, Coffin SE, Harrison JB, Swami SK, McGuire JL. Influenza-associated neurologic complications in hospitalized children. J Pediatr. 2021;239:24–31.e1. [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick T, McNally JD, Stukel TA, et al. Family and child risk factors for early-life RSV illness. Pediatrics. 2021;147(4):e2020029090. [CrossRef]

- CDC. How Flu Vaccine Effectiveness and Efficacy are Measured. (2023). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/vaccines-work/effectivenessqa.htm (accessed June 23, 2023).

- Kissling E, Pozo F, Martínez-Baz I, Buda S, Vilcu A-M, Domegan L, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness against Influenza A subtypes in Europe: Results from the 2021-22 I-MOVE primary care multicentre study. Influenza Other Respir Virus. (2022) 17:1–e13069. [CrossRef]

- Yildirim I, Kao CM, Tippett A, et al. A retrospective test-negative case-control study to evaluate influenza vaccine effectiveness in preventing hospitalizations in children. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(10):1759–1767. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The number of patients in the study groups, by influenza type.

Table 1.

Comparison of clinical outcomes by influenza virus type/subtype in pediatric population, p*=comparison between the Influenza A(H3N2) and A(H1N1). P**=comparison between Influenza A and A+B. p*** comparison between Influenza A and B.

Table 1.

Comparison of clinical outcomes by influenza virus type/subtype in pediatric population, p*=comparison between the Influenza A(H3N2) and A(H1N1). P**=comparison between Influenza A and A+B. p*** comparison between Influenza A and B.

| Parameter | Influenza A group (n=244) | Influenza A+B (n=19) | Influenza B (n=24) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | A(H3N2) (n= 33.6% |

A(H1N1) (n=66.4%) |

p* | p** | Total | Total | P*** | ||

| Gender n, (%) | |||||||||

| Male | 135(55.33) | 46(18.85) | 89(36.48) | 1.000 | 0.112 | 11(57.9) | 11(45.83) | 0.289 | |

| Female | 109(44.67) | 36(14.75) | 73(29.91) | 0.05 | 0.03 | 8(42.1) | 13(54.16) | 0.233 | |

| Age median [IQR], years | 3.478[2.6-6.2] | 3.338[2.28-7.125] | 0.1 | 0.005 | 3.21[1.91-4.33] | 6.228[5.13-9.29] | 0.001 | ||

| Age group in years at flu infection, n (%) | |||||||||

| 0–1 years | 7(2.87) | 32(13.11) | 0.005 | 0.01 | 6(31.58) | 2(8.33) | 0.15 | ||

| 2-3 years | 17(6.97) | 25(10.25) | 0.7 | 0.12 | 2(10.53) | 3(12.5) | 0.112 | ||

| 4–6 years | 21(8.6) | 29(11.89) | 0.075 | 0.07 | 3(15.79) | 6(25) | 0.5 | ||

| 7–12 years | 24(9.84) | 46(18.85) | 0.25 | 0.5 | 3(15.79) | 6(25) | 0.25 | ||

| 13-18 years | 13(5.33) | 30(12.3) | 0.125 | 0.5 | 5(26.32) | 7(29.17) | 0.017 | ||

| Clinical symptoms n(%) | |||||||||

| Fever | 240(98.36) | 81(33.2) | 159 (65.16) | 0.0001 | 0.001 | 19(100) | 22(91.67) | 0.626 | |

| Respiratory symptoms | 226 (92.7) | 89 (36.48) | 137(56.15) | 0.029 | 0.05 | 11 (94.5) | 18(75) | 0.566 | |

| Cough | 165 (83.2) | 58 (82.2) | 107(84.8) | 0.15 | 0.03 | 10 (84.6) | 14(58.33) | 0.027 | |

| Rhinorrhea | 210 (65.7) | 47(66.1) | 163 (61.7) | 0.06 | 0.093 | 13 (68.42) | 10(41.67) | 0.071 | |

| Sore throat | 189 (77.46) | 56 (22.95) | 133 (54.5) | 0.189 | 0.9 | 12 (63.16) | 8(33.33) | 0.303 | |

| Dyspnea | 68 (27.87) | 23 (9.43) | 45(18.44) | 0.001 | 0.567 | 5 (26.32) | 6(25) | 0.005 | |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms, n (%) | |||||||||

| Vomiting | 149 (61.07) | 108 (44.26) | 41 (16.8) | 0.246 | 0.04 | 7 (36.84) | 21(87.5) | 0.05 | |

| Abdominal pain | 151 (61.89) | 63 (25.82) | 88(36.07) | 0.327 | - | 0 (0) | 4(16.67) | 1.000 | |

| Diarrhea | 99 (40.57) | 30 (12.3) | 69 (28.29) | 0.599 | 0.001 | 3 (15.79) | 8(33.33) | 0.016 | |

| Other symptoms Myalgia |

143(58.6) |

46(18.85) |

97(39.75) |

0.233 |

0.112 |

7(36.84) |

8(33.33) |

0.017 |

|

| Treatment n(%) | |||||||||

| Antiviral therapy Oseltamivir | 205 (84.02) | 42 (76.2) | 163(66.8) | <0.001 | 0.023 | 16(84.21) | 20(83.33) | 0.05 | |

| Days of hospitalisation | 5[5-6] | 7[7-8] | 0.2 | 0.01 | 10[7-11] | 8[7-9] | 0.012 | ||

| Days of antiviral administrations (Oseltamivir) n = (number days), [IQR]. | 5[4-5] | 6[5-7] | 0.1 | 0.05 | 7[7-9] | 5[5-6] | 0.2 | ||

Table 2.

Complications Between Easy, Moderate and Severe Influenza Forms of the Pediatric Patients. (* comparison between the moderate and severe influenza groups).

Table 2.

Complications Between Easy, Moderate and Severe Influenza Forms of the Pediatric Patients. (* comparison between the moderate and severe influenza groups).

| Variable | Total (n=301) 100% |

Easy (n=60) 20% |

Moderate (n=185) 61.7% | Severe (n=56) 18.2% |

p-value * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender n,(%) male/female |

126(41.86) /175(58.14) | 28(46.6)/32 (53.3) | 75(40.5)/110 (59.46) | 23(41.07)/33 (58.92) | 0.048 |

| ENT involvement Sinusitis Acute otitis media |

41(13.62) 21(6.98) 20(6.64) |

18 (5.5) 7(2.33) 11(3.65) |

17(13.6) 9(2.99) 8(2.66) |

6(23.9) 5(1.66) 1(0.33) |

0.5 0.1 0.33 |

| Respiratory involvement Interstitial Pneumonia Secondary Bacterial Pneumonia RSV co-infection Fungal co-infections Bronchiolitis obliterans Laryngitis |

93(30.9) 27(8.97) 26(8.64) 12 (4) 11(3.65) 22(7.31) 18(5.98) |

14(23.3) 4(2) 3(0.996) 0 1(0.33) 1(0.33) 6(1.99) |

36 (19.4) 6(1.99) 10(3.32) 8(2.66) 3(1) 11(3.654) 9(2.99) |

43(76.1) 17 13(4.32) 4(2) 7(2.33) 10(3.32) 3(0.996) |

0.05 0.01 0.011 0.05 0.01 0.05 0.03 |

| Neurological manifestations Febrile seizure Acute encephalomyelitis Encephalitis |

6(2) 2(0.664) 3(0.996) 1(0.33) |

1(0.33) 0 2(0.664) 0 |

4(2.0) 2(0.664) 1(0.33) 0 |

1(0.33) 0 0 1(0.33) |

0.01 0.012 0.1 0.13 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Copyright: This open access article is published under a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license, which permit the free download, distribution, and reuse, provided that the author and preprint are cited in any reuse.

Clinical Features and Outcomes of Association of Co-infections in Children with LaboratoryConfirmed Influenza, during 2022–2023 Season; a Romanian Perspective

Maria Madalina Merisescu

et al.

,

2023

MDPI Initiatives

Important Links

© 2024 MDPI (Basel, Switzerland) unless otherwise stated