Preprint

Article

Adaptively Learnt Modeling for a Digital Twin of Hydropower Turbines with Application to a Pilot Testing System

Altmetrics

Downloads

113

Views

21

Comments

0

A peer-reviewed article of this preprint also exists.

This version is not peer-reviewed

Submitted:

04 September 2023

Posted:

06 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Alerts

Abstract

In the development of a digital twin (DT) for hydropower turbines, dynamic modeling of the system (e.g., penstock, turbine, speed control) is crucial, along with all the necessary data interface, virtualization, and dashboard designs. Since the DT must mimic the actual dynamics of the hydropower turbine accurately, adaptive learning is required to train these dynamic models online so that the models in the DT can effectively follow the representation of the actual hydropower turbine dynamics accurately and reliably. This study presents an adaptive learning method for obtaining the hydropower turbine models for DT development of hydropower systems using recursive least squares algorithm. To simplify the formulation, the hydropower turbine under consideration was assumed to operate near a fixed operating point, where the system dynamics can be well represented by a set of linear differential equations with constant parameters. In this context, the well-known six-coefficient model for the Francis turbine was formulated as the starting point to obtain input and output models for the turbine. Then, an adaptive learning mechanism was developed to learn model parameters using the real-time data from a hydropower turbine testing system. This led to a semi-physical modeling in which the first principles and data-driven modeling are integrated to produce dynamic models for the DT development. Applications to a pilot system at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) were made, and the models learned adaptively using the data collected from the university’s pilot system. Desired modeling and validation results were obtained.

Keywords:

Subject: Engineering - Electrical and Electronic Engineering

1. Introduction

With an average machine age of more than 64 years, the US hydropower fleet requires smart modernization to reduce costs and enhance the overall reliability and value of the nation’s longest-serving renewable energy technology. Hydropower operations are becoming more complex and demanding as hydropower increasingly provides grid reliability and resiliency while variable renewable energy production, such as solar and wind installations, continues to expand. As the electric power grid prioritizes reliability, resiliency, and value amidst an evolving mix of variable renewable and baseload assets, hydropower technology will require the integration and full benefit of the best available and future advancements in sensors, data and control systems, analytics, simulation, optimization, and computing capabilities to remain competitive. We refer to this need as the hydropower digitalization challenge; the development of a digital twin (DT) would be an effective solution to address such a challenge.

A DT is a combination of a real system and its coupled computational model [1,2,3]. DTs are a hallmark of advanced digitalization within an industry. Data and feedback within a DT provide capacities for autonomy, memory, and embedded intelligence that learn and respond to an evolving environment. This digital embodiment of physical system behavior enables improvements in performance, resource mobilization, asset management, investment planning, and scenario analyses. DT adoption has grown rapidly since its inception in 2003 to address needs for design, production, prognostics, and health management [4,5]. DTs are used to design new products in a responsive, efficient, and informed manner, and to synchronize design and production. DTs are also used to monitor, control, and optimize production processes reliably and flexibly—DT-enabled production optimization has reduced material waste and prolonged machine lifetime [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. However, DT market penetration is limited [6,7,8,9]; fewer than 15% of industries use DTs, and the rest have nascent or no plans to implement DTs in the next 5 years. DT development in the electric power sector, including hydropower, is nascent [10] but has been embraced by and benefitted the manufacturing. For example, the Turlough Hill hydroelectric plant in Ireland uses a DT to implement predictive maintenance, thereby improving reliability and reducing costs for an aging facility, but DT applications for hydropower systems are few [11].

In this context, Figure 1 shows the basic components of a DT for hydropower systems—an open platform framework, as described in [12]. It can be seen that the framework will collect data from real hydropower systems and continuously update its dynamic models for various components of hydropower systems. Thus, the DT can comprehensively represent the actual plant operation in a digital form for its use in the operational optimization, condition monitoring, and workforce training. The framework also has a powerful user interface, including visualization and augmented reality, to allow user-friendly functionalities for the hydropower industry usages, hydropower system equipment manufacturers, and academia.

Based on the described framework and requirements, in the development of a DT for hydropower systems, dynamic modeling of the system (such as the penstock, turbine, generator, and linkages to the power grid units) is important, in addition to all the necessary data interface, virtualization, and dashboard designs. Since the DT must mimic the actual dynamics of the hydropower system accurately, adaptive learning is required to train the dynamic models online so that the models in the DT can effectively and responsively follow the representation of the actual hydropower systems dynamics accurately and reliably. This effectiveness requires the integration of physical modeling with data-driven approaches to enable the models in the DT to learn and update their parameters in real time when new sets of data are collected from the reference hydropower systems, as shown in Figure 1. In this context, adaptive learning such as recursive least squares method [12,13] should be used together with the structure of the physical models [14,15] to learn the dynamics of the system. Indeed, parameter estimation and system identification have been used for hydropower systems for sometimes [16,17,18,19]. For example, a system identification method for estimating the relationship between the water level and generating power was developed in [16]. System identification has also been used to estimate transfer functions of hydropower dynamics for frequency containment reserves [17]. For nonlinear feature estimation, in [18] a neural network-based method has been developed for the predictive control of hydropower plant operational efficiency. In this context, an adaptive fuzzy particle swarm optimization approach has been used to estimate parameters of hydro-turbine regulation system [19].

In this work, we present an adaptive learning method to obtain the online models for hydropower turbines in the DT development of hydropower systems, as shown in Figure 1. We emphasize the establishment of adaptive modeling of water flow and turbine speed control systems. To simplify the formulation, we assumed that the system under consideration operates near a fixed operating point, where the system dynamics can be well represented by a set of linear differential equations with constant parameters [20]. In this context, the well-known six-coefficient models [21] for the Francis turbine was formulated as a starting point in the state space form. Once these state space physical models were established, a set of input and output models [13] were then obtained and an adaptive learning mechanism was developed to update input and output model parameters in real time using the data from the hydropower system [16]. This leads to a semi-physical modeling in which the first principles and data-driven modeling are effectively integrated to produce dynamic turbine models. Applications to a pilot testing system in the Water Power Laboratory at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) were made, and the models learned adaptively using the data collected from the test system with desired modeling and validation results.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 describes the formulation of the six-coefficients model for the Francis turbine in the state space form together with standard discretization. Section 3 describes the establishment of transfer functions based input and output models so that the hydropower turbine could be modeled by a set of transfer functions. Section 4 presents an adaptive learning algorithm using the recursive least squares learning principle in which the model parameters can be learned and updated using the real-time data. Section 5 describes applications to the testing hydropower system at NTNU, showing the effectiveness of the proposed adaptive learning strategy. Section 6 presents conclusions and future work. The nomenclature is defined in Table 1.

2. Turbine System Model

The water system for realizing electricity generation should consider the features from the reservoir, penstock, turbine chamber, and discharge (tail water stream), all of which together comprise a complex nonlinear hydropower dynamic system, which requires data-driven modeling and initial manufacturing data from turbine manufacturers. By using hydropower turbine-generator experimental data, we can construct a systematic model for simulating the hydropower generator system for DT development.

As shown in Figure 2, the operational system for hydropower turbine units consists of the penstock dynamics, turbine, speed sensor, speed controller and a hydraulic servo that amplifies the control output to drive the guide vane opening for the control of the water flow to the turbine.

3.1. Turbine Speed (Frequency) Control System

The control structure of the turbine speed is shown in Figure 2; the closed-loop system consists of dynamics of the turbine, hydraulic servo, and controller. For the hydropower turbine to be controlled, the input is the guide vane opening that controls the amount of water into the hydropower turbine, and the output is the shaft speed (frequency) and the water head. The objective of such a closed-loop control is to maintain the required shaft speed (frequency) subjected to the load changes as denoted by when the hydropower generation is connected to the power grid, and at the same time minimize the water head variations.

3.2. Torque and Water Flow Module

Figure 2 also shows the torque and water flow rate module when the generation unit operates. In the hydropower turbine dynamics for the mechanical torque and water flow rate, the inputs are the guide vane opening, the shaft speed, and the water head, respectively. The outputs are the turbine torque () and water flow rate ().

The following nonlinear functions are generally used:

where is the time-varying variable denoting the turbine speed (rad/s), which is related to the frequency through with being the turbine-generator frequency controlled around 50 Hz for the NTNU testing system when the hydropower generation unit is connected to the grid. In Eq. (1), is the water head and is the guide vane opening. are two unknown nonlinear functions that need to be learned using the operational real-time data from the actual plant.

Throughout this paper it is assumed that the turbine operates at a selected fixed operating point, , for the hydropower generation unit connected to the grid. Based on the fixed operating point , the relative (normalized) incremental values of turbine shaft speed, water head, water flow rate, guide vane opening and torque are defined as follows.

where is the normalized incremental value for the shaft speed, is the normalized incremental water head, is the normalized incremental water flow rate, and is the normalized incremental guide vane opening, and is the normalized incremental mechanical torque with being the turbine operating torque that maintains the operating point . Since , , , m and are all normalized incremental variables, they do not have physical units.

Using definitions in Eq. (2-1), the nonlinear dynamics of the mechanical torque and water flow rate can be linearized to provide the following six-coefficient linearized dynamic model for the normalized incremental torque () and the normalized incremental water flow rate () of the turbine [21].

where , , and are the linearized coefficients for the torque generation calculated at a fixed operating point . , , and are the linearized coefficients for the water flow rate calculated at a fixed operating point . These six coefficients [21] are obtained from:

These constants can be estimated based on the experimental data. Using these definitions, the shaft rotation can be expressed by the following dynamics (i.e., the swing equation):

where is a load torque in normalized incremental sense and with being the inertia.

3.3. State Space Model for Non-elasticity Water System Dynamics

When the water in the penstock is incompressible, the system is regarded as nonelastic [22,23]. In this case, the relationship between the water head and the water flow rate is:

In Eq. (5), the input is the normalized incremental water flow rate (), and the output is the normalized incremental water head (), as defined in Eq. (2-1), and is the water inertia time constant, which is defined as:

where is the length of penstock pipeline, and and are from the operating point . For the NTNU testing system used in this study, 0.0415 m2·s. By integrating the linearized Eqs. (3) to (5) into a state space format, the following state space model can be readily obtained.

where , , , and are formulated using the six-coefficient linearized models in Eqs. (3) – (5) to give:

In the system, the input is the normalized incremental value of the guide vane opening and its rate of changes, and the outputs are the shaft speed and the water head. Figure 3 shows such a state space model structure.

The open-loop stability of the hydropower turbine can be ensured if all the eigenvalues of are inside the left-hand side of the complex plane. The turbine torque is used to balance the grid load which can be generally expressed as:

where is the damping ratio contributed by the power grid, and is the load, which is assumed here to be less than 10% of total load variations since large load changes would trigger the nonlinearities of the mechanical torque and water flow rate and make the linearized model unsuitable.

3.4. State Space Model for Elastic Water Flows

Again, for linearized modeling, nonelastic water flow was considered for large water head and long penstock. In this case, the following better approximated water system dynamics are used [23]:

This transfer function shows the second order dynamics between the water head and the water flow rate. In Eq (10),

where is the wave travel time, “” is the Laplace variable, and = 1,480 m/s is the velocity of the sound travelling in the water.

Thus, the following time domain differential equation can be formulated, which links the water flow rate to the water head in the normalized incremental sense as defined in Eq. (2-1) for the hydropower turbine.

In this case the state vector for the penstock dynamics is denoted as:

Then, the following penstock state space model can be obtained:

where is regarded as a kind of calculatable input to the penstock system for elastic water flows. Further formulation of Eq. (12) using the six-coefficient model and Eq. (4) leads to:

Combining these two equations gives:

At this stage, the extended state vector is denoted as:

Then, the following state space model of the whole turbine dynamics for the elastic water flow can be obtained.

In this case, the state space form can be represented as:

where system matrices in Eq. (8) become:

This format indicates that the system has third order dynamics—again subjected to the inputs of the normalized incremental values of the guide vane opening and its rate of changes, as shown in Figure 3.

These open-loop state space models can be further transferred into a direct input and output models that help to construct the adaptive learning algorithms that use available collected real-time data to learn the component models of the hydropower turbine and estimate relevant model parameters.

3.5. PID Controller for Shaft Speed

The open-loop system structure shown in Figure 3 can be integrated with the controller (speed governor) to form a typical closed-loop control system for the shaft speed as shown in Figure 2. In this context, the controller should be designed so that the shaft speed is well controlled within its targeted set point ranges with minimal variation in the water head, and it should be subjected to the operational constraint on the rate of changes for the guide vane opening as well. In this context, the widely used PID controller has the following form [23].

where is the tracking error of the normalized incremental shaft speed, is the output of the controller (i.e., the output of the speed governor of the hydropower turbine as shown in Figure 2), is the proportional gain, is the integral gain, is the derivative gain, and is the time. The selection of these control gains was determined from the test rig at NTNU during the test runs.

3.6. Discretization

The control design objective is to obtain the speed control signal, the governor’s output , so that optimally tracks zero with a required bounded rate of changes. Considering that the system in either Eq. (8) or Eq. (18) is linear time-invariant, this study uses the discretization equations as follows:

where, is the sampling time interval for the discretization. By applying this discretization to the state space models, the discretized model can be obtained. For the NTNU test rig, 0.2 s, indicating that there are five sampled points per second.

3.6. Hydraulic Servo for the Guide Vane Opening

The output of the speed controller will normally be amplified by a hydraulic servo system that has enough power to operate the movement of the guide vane. The guide vane opening is denoted as .

In general, the hydraulic servo in the waterpower laboratory at NTNU can be modeled in the discretized format as a second order dynamics at sampling interval seconds.

where is the output of the hydraulic servo which is also the guide vane opening, and is the output of the speed controller as shown in Figure 2.

3. Discretized Input and Output Models

To facilitate the estimation of the system parameters, the following transfer function models will be formulated using the state space model in Eqs. (8) and (18).

The objective was to obtain the relationship between the input (guide vane opening) and the outputs (the shaft speed and the water head). For this purpose, these input and output models were formulated in the Laplace transformation domain. Moreover, nonelastic and elastic water flow were both considered.

3.1. Input and Output Model for Nonelastic Water Flow

When the system is under nonelastic water flow with constant load (, in the Laplace transform format the following equations reveal the relationship of the shaft speed and the water head with respect to the guide vane opening.

where “” in Eq. (22) denotes the Laplace variable.

Also, to simplify the representation, when the variables such as are used together with the Laplace variable “s”, they are inherently in their Laplace transformed senses.

By solving the water head from Eq. (22-2), the following can be obtained:

By substituting Eq. (23) into Eq. (22-1) and rearranging all the terms, the following can be obtained:

Thus, the relationship between and for nonelastic water flow is given as:

where it has been denoted that:

Accordingly, the transfer function between and is:

To summarize, we have:

Eqs. (26-2) and (26-3) reveal how the guide vane opening affects the shaft speed and water head during system operation under nonelastic water flow. In the next subsection, similar models for elastic water flow are formulated.

3.2. Input and Output Model for Elastic Water Flow

In case the water is compressible, simple second order dynamics as shown in Eq. (10) can be used. Using this elastic water model for penstock, a similar formulation to the Eqs. (22) – (26) can also be performed to obtain the input and output models for the guide vane opening, shaft speed, and water head. For example, Eq. (22-1) stays the same, and the water head and flow rate dynamics become:

Re-arranging Eq. (28) leads to the following model:

which reveals the relationship of the water head with respect to the speed and the guide vane opening as the control input.

Substituting Eq. (29) into Eq. (22-1) and eliminating leads to the following direct relationship between the shaft speed and the guide vane opening

where it can be formulated that

which are third order and second order polynomials, respectively. As in general , the denominator in Eq. (30-1) satisfies the necessary condition for the stability for the speed system.

Eq. (30) shows that the dynamics between the shaft speed and guide vane opening follow a third order differential equation when the water flow is elastic.

4. Least Squares Adaptive Learning Scheme Using Real-time Data for Elastic Water Flows Case

Using the models developed in Section 3, relevant learning strategies can be obtained for estimating the input and output model parameters using the sampled data from the actual system. In this context, only the system with elastic water flow was examined since the nonelastic water flow has simpler equations in describing the dynamics among the guide vane opening, shaft speed, and water head.

Eq. (30) shows that the system is a third order for elastic water flow between the guide vane opening and the shaft speed. In this context, the discretization using Eq. (20) would lead to the following discretized input and output model between the shaft speed and the guide vane opening [13].

where and are the sampled shaft speed and guide vane opening of the turbine in their normalized incremental senses, respectively. is the sampling index, is the sampling period as denoted before, and is related to the discretized and normalized incremental value of the load torque with being a coefficient. , , , , , and are the coefficients to calibrate.

Assuming that the data are collected from the test runs in which the load is constant, then in most cases, and the estimation of is not necessary. Furthermore, are coefficients as a result of discretization, and they are complicated functions of the six coefficients defined in Eq. (2) and other parameters in the state space model represented in Eqs. (18-1) and (18-2).

Assuming that the real-time data can be collected and denoted as the data sequence of , then the objective of parameter learning for the input and output model is to use these collected input and output data to estimate the model parameters in Eq. (31). Of course, once these parameters are well estimated, the original six coefficients inside the state space model can be formulated using the inverse mapping between model parameters in Eq. (31) and the six coefficients in the state space model. For this purpose, we denote:

Then, when the test runs for the data collection are under a fixed load condition, Eq. (31) can be simply expressed by:

Assuming that the current sample time is and the data have been available from up to , the least squares algorithm can simply be used to recursively estimate the parameters as shown in the following form.

where is the estimate of at sample time , and is a variance matrix calculated from Eq. (34-3). The initial values of (k) and are prespecified depending on the prior knowledge of the parameter values. The structure of the adaptive learning is shown in Figure 4.

Eq. (34) constitutes a learning strategy to estimate model parameters and ultimately the six coefficients. Once the parameters are estimated, they would constitute an adaptive modeling for the hydropower turbine.

In the same way, the model for water head can also be learned adaptively. Eq. (12) shows that the discretized model of the water head is of the following form:

Therefore, Eq. (35) can be further expressed in the following vector form – Eq. (36) which is similar to that in Eq. (33):

Thus, the similar recursive least squares algorithm to that in Eq. (34) can be modified to estimate , where the adaptive learning structure is again similar to that in Figure 4.

5. Experimental and Data Processing

This section describes the hydropower experimental data collection at NTNU and the process for estimating the model parameters in Section 4. For this purpose, a hydropower system control experiment was conducted, and the data were collected by collaborators at NTNU. The system structure is shown in Figure 5, where the water head ranged from 12 to 30 m and the flow rate ranged from 0.1 to 0.4 m3/s during testing and data collection.

The main variables measured and collected were the shaft speed, flow rate, pressure difference (i.e., water head) between inlet and outlet pressures, guide vane opening, mechanical torque, and load torque. The goal of processing the experimental data was to obtain the normalized values for these variables and ensure that they were uniformly sampled for the discretization models. The variables are summarized in Table 2. Six measurements of these variables were collected in the experiment in the waterpower laboratory at NTNU. Since the sampling interval for these variables was from different sensors, the sample frequency and total sample size from the sensors varied significantly. For example, the samples collected for the differential pressure were around 506 per 0.1 s, whereas the samples collected for the turbine speed were 4–7 per one second. Therefore, to consistently use the data, preprocessing was needed to clean up unnecessary information from the experimental data and unify the data sampling frequency, which were then used for discretized models in Eqs. (31) and (35).

Six groups of tests were conducted with changes in experiment conditions at the test rig at NTNU in June and July 2022. First, four open-loop tests (Tests 1–4) were conducted in which the guide vane opening () was directly changed while keeping other initial conditions fixed; the system load was fixed at 378 N·m, and the power generated was 14.9 kW. In this experiment, the maximum guide vane opening angle was 14°.

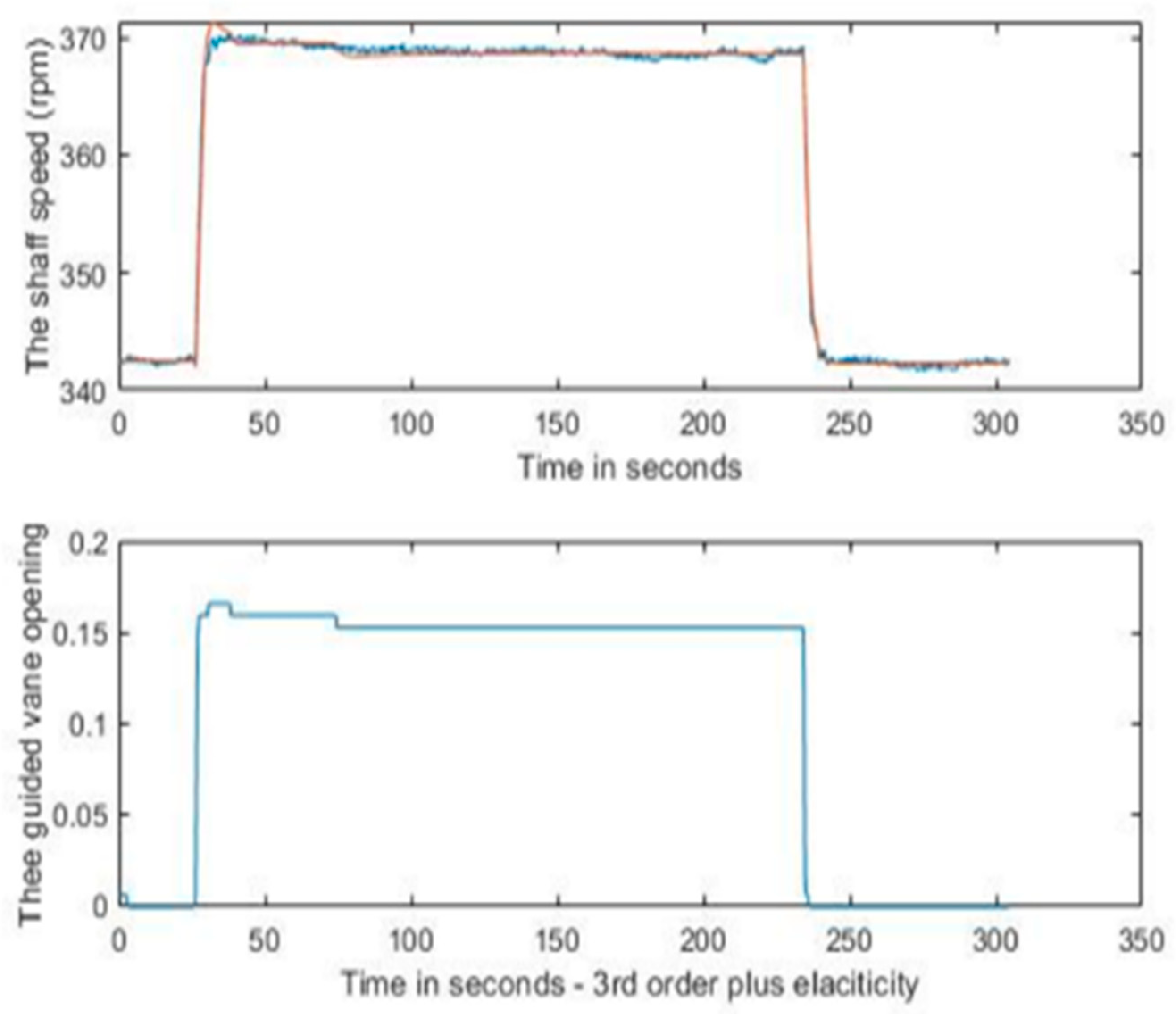

In Test 1, the guide vane opening went from 6.63° to 7.63°; in Test 2, it went from 7.60° to 6.60°; in Test 3, it went from 6.60° to 5.60°; in Test 4, it went from 5.60° to 6.60°. These changes reflect the open-loop tests in which the input was the guide vane opening and the outputs were the other variables in Table 2. In addition to the open-loop tests, two closed-loop tests (Tests 5 and 6) were conducted. Test 5 was carried out by changing the shaft speed set point from 342 to 360 rpm with speed control PI gains at = 7.5 and = 0.5. Test 6 was carried out by changing the shaft speed set point from 360 to 342 rpm at = 7.5 and = 0.15. The recursive least squares method in Eq. (34) was used to learn the system parameters grouped in given by Eq. (32-1), and the estimated outputs of the shaft speed, water head, and water flow rate were calculated using the estimated model parameters and compared with the actual system response data. The sampling frequency of turbine shaft speed (rpm) was used as the reference for unifying the data collection frequency. Therefore, the sample data were collected approximately every 0.2 s. For the measurements with sampling frequencies different from the sampling frequency of the turbine shaft speed (rpm), the value of the sample at the same time as the turbine shaft speed (rpm) sample was obtained through interpolation.

Also, all the responses of shaft speed, guide vane opening, water flow and water head were in the normalized incremental sense as defined in Eq. (2-1) except the shaft speed in Figure 7 and Figure 12, which are of the true values. The operating point in the test runs was selected as follows:

In the test runs, the magnitudes of perturbations of the guide vane opening for the open-loop tests and the set point of the shaft speed were less than ±1° and ±18 rpm, respectively. These values are of sufficiently small magnitudes to ensure that the assumption on linearization is satisfied. With such small magnitudes of input changes, the formulation of the models in Sections 2 to 4 are valid in representing the linearized dynamics of the system.

3.1. Learning of Input and Output Models for Elastic Case

In the learning, the first two open-loop testing data were combined in the data preprocessing stage. Figure 6 shows the responses of the six variables in normalized incremental sense.

In applying the adaptive learning algorithm in Eq. (34), the initial and the variance matrix were selected with being the 5 × 5 identity matrix.

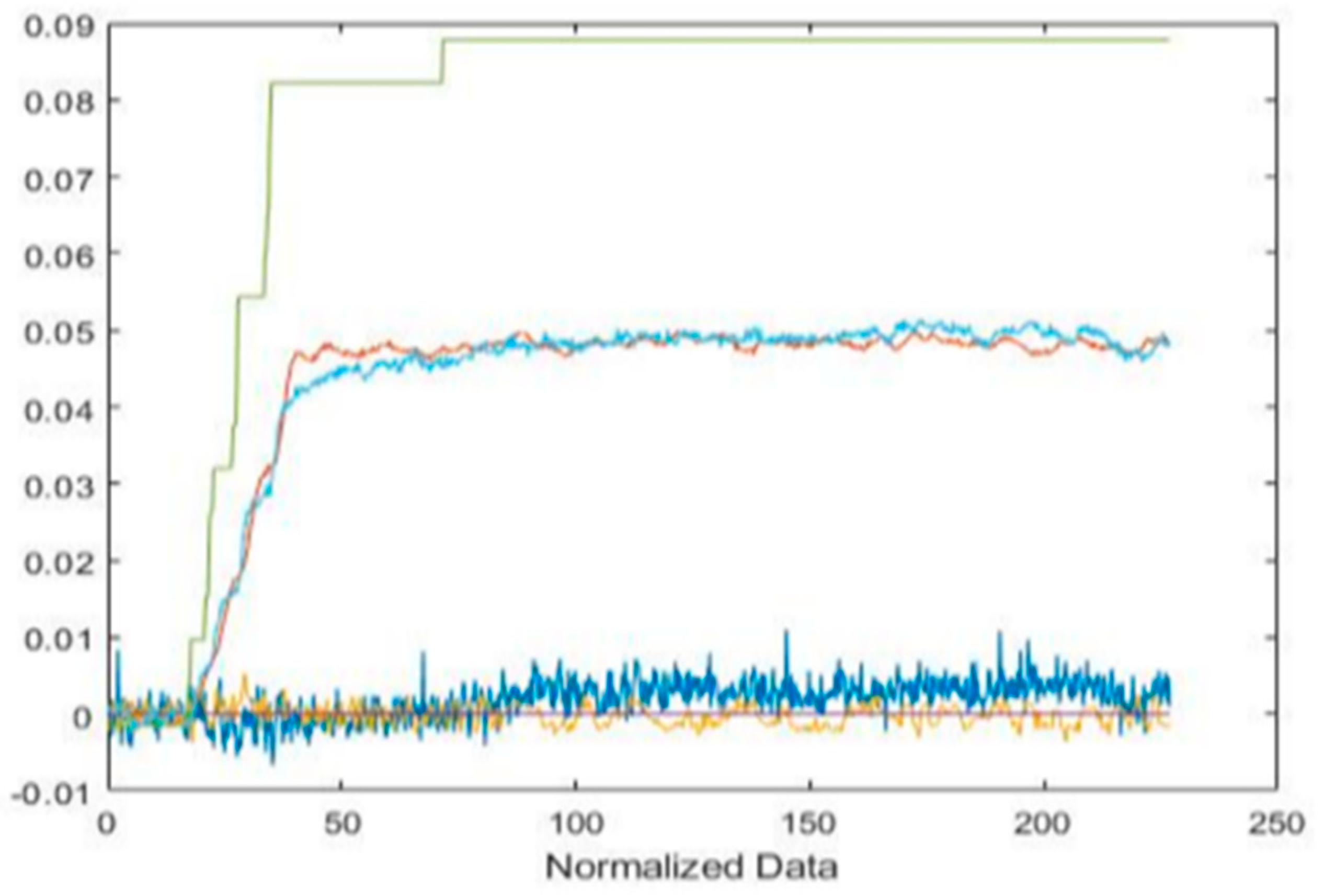

Figure 7 shows the two responses of the shaft speed in the top diagram; the blue line represents the original actual speed response , and the red line represents the estimated shaft speed (k) in the progress of the adaptive learning using the recursive least squares algorithm in Eq. (34). This has clearly demonstrated the desired adaptive learning effect as these two variables are very close to each other. In this case, the estimated shaft speed was calculated from the following model.

Eq. (37) shows the learned model, and the modeling error for the shaft speed is thus defined as:

This modeling error is different from the residual signal in the adaptive learning algorithm Eq. (34) because is different in the two equations. The model uses the same guide vane opening as presented in Figure 4. In Figure 7, the bottom diagram provides the actual system input—the guide vane opening in its normalized incremental values.

Figure 8 shows the modeling error reflected by the calculation in Eq. (37-3) when the adaptive learning phase in Eq. (34) is progressing. As shown in Figure 8, the modeling error was less than 1% in general. The maximum absolute modeling error was 0.84%. On the other hand, for the water head, the learned model is given by:

Accordingly, Figure 9 and Figure 10 show the responses of the actual and estimated water flow rate and water head with blue colored curve for the real-data and red colored curve as the model outputs. The figures also confirm that the desired learning effect was obtained.

At the end of the run for tests 1 and 2, the estimated has the following value:

Therefore, since for Tests 1 and 2, the discretized model for the shaft speed and the guide vane open is given by:

Similarly, after the test runs and adaptive learning application, the estimated parameters for the water head model are given by , which indicates that the model for the water head is:

Since the water starting constant is at a constant 0.0415 in the NTNU test rig, Eq. (40) becomes:

For Test 5, the actual system responses are shown in Figure 11, all in the normalized incremental sense.

Again, using the adaptive learning algorithm in Eqs. (34) and (36), the estimated values of the shaft speed, water flow rate, and pressure were obtained. The estimated variables were calculated using Eq. (39), which resulted in the responses in Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14.

Again, all the actual and estimated system responses were very close to each other, demonstrated the desired learning and estimation effects. These responses can be regarded as a side-by-side simulation when the DT is linked in parallel to the actual hydropower turbine unit in a synchronous time manner. In this case, the DT must generate the synchronized close-to-actual system responses to ensure that it can accurately learn the dynamics of the system.

3.2. Direct Estimate of the Six Coefficients

Since for the NTNU hydropower testing rig the mechanical-torque and the water flow rate can be directly measured together with the shaft speed, water head, and guide vane opening, we can also use Eq. (2) to obtain the least squares estimate of the six coefficients [21] at the operating point defined by:

In this context, the matrix-form of the least squares method for calculating these six coefficients through the batched data is shown in Eq. (42) as follows.

where is the column of the normalized incremental values of the turbine speed, is the column of the normalized incremental values of the water head, is the column of the normalized incremental values of the guide vane opening, is the column of the normalized incremental values of the turbine mechanical torque, and finally is the column of the normalized values of the water flow rate.

Thus, for test runs 1 and 2 the six-coefficient {, , , , , } is estimated using Eq. (42) to be as {−0.1438, 0.1513, 0.1178, −0.0222, 0.0646, 0.0026}.

6. Conclusions

In this study, an adaptive learning model was developed for hydropower turbines using the recursive least squares approach as the learning strategy for the initial development of a DT for hydropower systems. Under the assumption that the system operates near a fixed operating point defined by the shaft speed, water flow rate, water head, and guide vane opening, a set of linearized models was formulated in the state space and input and output forms using six-coefficient modeling in hydropower turbine modeling. The recursive least squares learning was then established to estimate the model parameters of the input and output models for the shaft speed and water head. The desired modeling results were obtained through a set of experiments on a Francis turbine in the Waterpower Laboratory test rig at NTNU. The model outputs closely tracked the actual system outputs effectively with very small tracking error, demonstrating the potential of using the developed adaptive learning for the DT development in the near future. Moreover, since the NTNU test rig can directly measure the mechanical torque and water flow rate, a direct estimation of the six coefficients was also made using the least squares algorithm.

The work reported here focused on adaptive learning models for hydropower turbine alone. Future efforts will be needed to include a synchronous generator in the modeling so that an adaptive learning modeling for the whole hydropower generating unit can be obtained. In addition, considering the large variation of dynamics, nonlinear system modeling using integrated physical modeling and data driven approaches (such as neural networks) are needed as well to capture the nonlinearities of the system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.W.; methodology, H.W.; software, S.O.; validation, H.W., and S.O.; formal analysis, H.W., and S.O.; investigation, H.W., and S.O.; resources, P.S., O.D., H.S., and I.V.; data curation, P.S., and O.G.; writing—original draft preparation, H.W., and S.O.; writing—review and editing, H.W., and S.O.; visualization, H.W., and S.O.; supervision, H.W.; project administration, H.W.; funding acquisition, H.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the DOE’s Water Power Technologies Office and used resources at the National Transportation Research Center at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, a User Facility of DOE’s Office Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript has been authored by UT-Battelle, LLC, under contract DE-AC05-00OR22725 with the US Department of Energy (DOE). The US government retains and the publisher, by accepting the article for publication, acknowledges that the US government retains a nonexclusive, paid-up, irrevocable, worldwide license to publish or reproduce the published form of this manuscript, or allow others to do so, for US government purposes. DOE will provide public access to these results of federally sponsored research in accordance with theDOE Public Access Plan (http://energy.gov/downloads/doepublic-access-plan).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- ARUP Digital Twin: Towards A Meaningful Framework; London, United Kingdom, 2019.

- Parrott, A.; Warshaw, L. Industry 4.0 And The Digital Twin: Manufacturing Meets Its Match; Olathe, Kansas, 2017.

- Tao, F.; Zhang, H.; Liu, A.; Nee, A.Y.C. Digital Twin in Industry: State-of-the-Art. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informatics 2019, 15, 2405–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vachálek, J.; Bartalský, L.; Rovný, O.; Šišmišová, D.; Morháč, M.; Lokšík, M. The digital twin of an industrial production line within the industry 4.0 concept. In Proceedings of the 2017 21st International Conference on Process Control (PC); 2017; pp. 258–262.

- Knapp, G.L.; Mukherjee, T.; Zuback, J.S.; Wei, H.L.; Palmer, T.A.; De, A.; DebRoy, T. Building blocks for a digital twin of additive manufacturing. Acta Mater. 2017, 135, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, K.; Omale, G. Gartner Survey Reveals Digital Twins Are Entering Mainstream Use. Available online: https://www.gartner.com/en/newsroom/press-releases/2019-02-20-gartner-survey-reveals-digital-twins-are-entering-mai (accessed on 13 October 2022).

- Goasduff, L. Confront Key Challenges to Boost Digital Twin Success. Available online: https://www.gartner.com/smarterwithgartner/confront-key-challenges-to-boost-digital-twin-success (accessed on 13 October 2022).

- Kosan, L. Digital Twin Technology: Where Are We Now? Available online: https://www.iotworldtoday.com/2019/05/08/digital-twin-technology-where-are-we-now/ (accessed on 13 October 2022).

- Martynova, O. Digital Twin Technology: A Guide for Innovative Technology. Available online: https://intellias.com/digital-twin-technology-guide/ (accessed on 13 October 2022).

- Lund, A.M.; Mochel, K.; Lin, J.-W.; Onetto, R.; Srinivasan, J.; Gregg, P.; Bergman, J.E.; Hartling, K.D.; Ahmed, J.A.; Chotai, S. Digital Wind Farm System 2016.

- Water Power Technologies Office Water Power Technologies Office Releases First Multi-Year Program Plan; Washington, DC United States, 2022.

- Wang, H.; Ahmed, O.; Smith, B.T.; Bellgraph, B. Developing a digital twin for hydropower systems - an open platform framework. Int. Water Power Dam Constr. Mag. 2021, 81. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Liu, Y.Q.; You, D.H. Application of a Nonlinear Self-tuning Controller for Regulating the Speed of a Hydraulic Turbine. J. Dyn. Syst. Meas. Control 1991, 113, 541–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giosio, D.R.; Henderson, A.D.; Walker, J.M.; Brandner, P.A. Physics-Based Hydraulic Turbine Model for System Dynamic Studies. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2017, 32, 1161–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennacchi, P.; Chatterton, S.; Vania, A. Modeling of the dynamic response of a Francis turbine. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2012, 29, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracino, R.; Hansen, V.; Goia, L.; Campo, A.; Campos, B. System Identification of a Small Hydropower Plant. In Proceedings of the 2021 14th IEEE International Conference on Industry Applications (INDUSCON); 2021; pp. 1430–1434.

- Jakobsen, S.H.; Bombois, X.; Uhlen, K. Non-intrusive identification of hydro power plants’ dynamics using control system measurements. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2020, 122, 106180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedayo, O.O.; Gbadamosi, S.L.; Ale, D.T. Neural Network Predictive Controller for Improved Operational Efficiency of Shiroro Hydropower Plant. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 2015, 6, 1454–1459. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.; Xiao, Z.; Li, H.; Liu, D.; Hu, X.; Malik, O.P. Accurate Parameter Estimation of a Hydro-Turbine Regulation System Using Adaptive Fuzzy Particle Swarm Optimization. Energies 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Zhang, L.X.; Qian, J.; Guo, Y.K.; Xu, T.M. Additional Mechanical Torque Coefficients of Hydro Turbine and Governor System. Adv. Mater. Res. 2012, 443–444, 954–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, D.; Zhang, H.; Wang, F.; Ba, D. Nonlinear modeling and dynamic analysis of a hydro-turbine governing system in the process of sudden load increase transient. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2016, 80, 414–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Shen, Z. Modeling and Simulation of Hydraulic Transients for Hydropower Plants. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE/PES Transmission & Distribution Conference & Exposition: Asia and Pacific; Dalian, China, 2005; pp. 1–4.

- Yang, W. Hydropower plants and power systems: Dynamic processes and control for stable and efficient operation, Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis: Electricity, Department of Engineering Sciences, Technology, Disciplinary Domain of Science and Technology, Uppsala University, 2017.

Figure 1.

The structure of a DT for hydropower systems.

Figure 2.

Control flow of the hydropower turbine control system.

Figure 3.

Open-loop system structure.

Figure 4.

Adaptive learning of parameters θ for elastic water flow.

Figure 5.

Structure of the hydropower generator system.

Figure 6.

Data of normalized incremental responses of shaft speed, water flow rate, water head, torque, and guide vane opening collected for Tests 1 and 2.

Figure 6.

Data of normalized incremental responses of shaft speed, water flow rate, water head, torque, and guide vane opening collected for Tests 1 and 2.

Figure 7.

Shaft speed in rmp, its estimated value , and the guide vane opening in its normalized incremental value.

Figure 7.

Shaft speed in rmp, its estimated value , and the guide vane opening in its normalized incremental value.

Figure 8.

Response of the shaft speed modeling error when the adaptive learning Eq. (34) is progressing for Tests 1 and 2.

Figure 8.

Response of the shaft speed modeling error when the adaptive learning Eq. (34) is progressing for Tests 1 and 2.

Figure 9.

Actual and estimated water flow rate in normalized incremental values.

Figure 10.

Actual and estimated water head in normalized incremental values.

Figure 11.

Actual system responses of shaft speed, water flow rate, pressure, guide vane opening, and torque all in the normalized incremental sense as in Eq. (2-1).

Figure 11.

Actual system responses of shaft speed, water flow rate, pressure, guide vane opening, and torque all in the normalized incremental sense as in Eq. (2-1).

Figure 12.

Top: Actual and estimated shaft speed in rpm, and bottom: actual guide vane opening in its normalized incremental values in the closed loop shaft speed control mode.

Figure 12.

Top: Actual and estimated shaft speed in rpm, and bottom: actual guide vane opening in its normalized incremental values in the closed loop shaft speed control mode.

Figure 13.

Actual and estimated water flow rate in the normalized incremental values – blue line stands for real data and red line for the model output.

Figure 13.

Actual and estimated water flow rate in the normalized incremental values – blue line stands for real data and red line for the model output.

Figure 14.

Actual (blue) and estimated (red) water head in its normalized incremental values.

Table 1.

Nomenclature.

| Symbol | Description |

|---|---|

| grid interface parameter | |

| turbine interface parameter | |

| damping ratio contributed by the power grid | |

| tracking error of the incremental speed control for the incremental shaft speed | |

| , , | linearized coefficients for the water flow rate () calculated at a fixed operating point O |

| , , | linearized coefficients for the turbine torque () calculated at a fixed operating point O |

| normalized incremental water head | |

| water head (time-variant) | |

| average water head | |

| equivalent inertia | |

| integral gain in the speed controller | |

| integral gain in the voltage controller | |

| proportional gain in the speed controller | |

| length of the water pipeline | |

| equivalent load when connected to the grid | |

| normalized turbine torque | |

| load torque | |

| turbine torque (time-variant) | |

| average turbine torque | |

| a selected and fixed operating point for the hydropower generation unit connected to the grid | |

| normalized incremental water flow rate | |

| water flow rate (time-variant) | |

| average water flow rate | |

| water inertia time constant | |

| guide vane opening (time-variant) | |

| average guide vane opening | |

| set point of active power, which reflects the power demand from the grid | |

| The output of the governor (speed controller) | |

| normalized incremental turbine shaft speed | |

| time interval, 0.2 s | |

| turbine shaft speed (time-variant) | |

| average turbine shaft speed | |

| normalized incremental guide vane opening angle | |

| guide vane opening angle | |

| grid interface parameter | |

| turbine interface parameter | |

| damping ratio contributed by the power grid | |

| tracking error of the incremental speed control for the incremental shaft speed | |

| , , | linearized coefficients for the water flow rate () calculated at a fixed operating point O |

| , , | linearized coefficients for the turbine torque () calculated at a fixed operating point O |

| normalized incremental water head | |

| water head (time-variant) | |

| average water head | |

| equivalent inertia | |

| integral gain in the speed controller | |

| integral gain in the voltage controller | |

| proportional gain in the speed controller | |

| length of the water pipeline | |

| equivalent load when connected to the grid | |

| normalized turbine torque | |

| load torque | |

| turbine torque (time-variant) | |

| average turbine torque | |

| a selected and fixed operating point for the hydropower generation unit connected to the grid | |

| normalized incremental water flow rate | |

| water flow rate (time-variant) | |

| average water flow rate | |

| water inertia time constant | |

| guide vane opening (time-variant) | |

| average guide vane opening | |

| set point of active power, which reflects the power demand from the grid | |

| The output of the governor (speed controller) | |

| normalized incremental turbine shaft speed | |

| time interval, 0.2 s | |

| turbine shaft speed (time-variant) | |

| average turbine shaft speed | |

| normalized incremental guide vane opening angle | |

| guide vane opening angle |

Table 2.

Experimental data summary.

| Variable | Unit | Average sampling frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Water head (H) | Pa | 5,060/s |

| Water flow rate (Q) | m3/s | 5,060/s |

| Turbine torque (M) | N·m | 5,060/s |

| Load torque (L) | N·m | 5,060/s |

| Guide vane opening angle (u) | ° | 10/s |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Copyright: This open access article is published under a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license, which permit the free download, distribution, and reuse, provided that the author and preprint are cited in any reuse.

Adaptively Learnt Modeling for a Digital Twin of Hydropower Turbines with Application to a Pilot Testing System

Hong Wang

et al.

,

2023

Predicting the Related Parameters of Vortex Bladeless Wind Turbine by Using Deep Learning Method

Mahsa Dehghan Manshadi

et al.

,

2021

MDPI Initiatives

Important Links

© 2024 MDPI (Basel, Switzerland) unless otherwise stated