Preprint

Article

Is Frequency of Practice of Different Types of Physical Activity Associated with Health and a Healthy Lifestyle at Different Ages?

Altmetrics

Downloads

97

Views

31

Comments

0

A peer-reviewed article of this preprint also exists.

This version is not peer-reviewed

Submitted:

30 October 2023

Posted:

31 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Alerts

Abstract

Several studies have shown that physical activity (PA) is related to physical and mental health. Yet, there are few studies on the frequency of PA as it relates to health and a healthy lifestyle. The purpose of this study was to investigate the relationship between the frequency of practicing different types of physical activities (dependent variables), living a healthy lifestyle (BMI, smoking and alcohol consumption), physical health (sum of all doctor visits except psychiatrists) and mental health (a sum of visits to psychiatrists) at different ages (independent variables). We fo-cused on three types of PA: (1) medium to high-intensity aerobic exercises; (2) low to medium intensity relaxing and stretching exercises, (3) outdoor leisure PA. 9,617 participants (ages: 19 -81) were included in the study (with health registries over a period of 10 years prior to a cross-sectional survey). Descriptive statistics and multinomial logistic regression on frequencies of three types of PA and factors related to health and healthy lifestyles, as well as age and sex, were performed in this study. The results indicate that a higher frequency of practicing PA had a higher probability of association with the following factors: lower BMI, less or non-smoking behavior (types 1 & 3); higher education (types 1 & 2); higher age (types 2 & 3) and better physical health (type 1). Occasional (practicing sometimes) PA, type 2, was positively associated with poorer mental health (higher number of psychiatrist visits). Women were more likely to practice PA type 2, and men – PA types 3 & 1. Conclusion: In general, a higher frequency of PA is related with better health and healthy life styles; with the exception of PA type 2 that is related to poorer mental health.

Keywords:

Subject: Public Health and Healthcare - Physical Therapy, Sports Therapy and Rehabilitation

1. Introduction

Physical activity (PA) is a vague term that can refer to a broad range of activities with varying levels of intensity and frequency. In the most general sense it is defined as an increase of energy expenditure by moving one’s body [1,2]. Some researchers have mentioned the importance of covering different domains of physical activity instead of referring only to sport and exercise. These domains are walking, cycling, leisure time, housework, transportation, and occupational physical activity [3,4,5,6,7,8]. The World Health Organization states that globally, one in four adults do not meet the global recommended levels of physical activity [9]. Regular physical activity has been proven to help prevent and manage non-communicable diseases such as heart disease, stroke, diabetes, several cancers, hypertension; aid the maintenance of a healthy body weight (normal BMI – body mass index); and can improve mental health, quality of life and well-being [9,10,11,12,13,14]. It was reported as effective as an adjuvant treatment in major depressive disorder [15], helping improve functioning parameters in depressed patients and lowering depression symptoms. Aerobic exercises were found effective in reducing depression symptoms [16]. Adding high-intensity exercise to aerobic training was found efficacious in improving mood and depression levels [17]. Yoga-type, stretching and resistance training exercises were reported as effective coping strategies for reducing levels of anxiety [18]. They also help maintain cognitive function [6,19,20]. Adequate levels of physical activity have been shown to result in emotional well-being and increased energy [7].

In different papers physical activity is classified into different levels, most often high (e.g. jogging, swimming, training at a gym, tennis), moderate (e.g. daily walking for at least 1 hour ) and low [4,5]. In their position statement on physical activity and exercise intensity terminology, Norton, Norton, and Sadgrove [10] offered a more distinct designation of physical activity: sedentary, light, moderate, vigorous and high [10]. The Youth Compendium [3] provided a list of 196 physical activities categorized by activity types, specific activities, and metabolic costs. For the purpose of our study, we focused on several levels and types of physical activity: (1) medium to high-intensity exercises (running, aerobics, swimming) (PA type 1), (2) low to medium intensity, stretching exercises (e.g. yoga, Tai-Chi, stretching, Pilates, etc.) (PA type 2), and (3) outdoor leisure group sport and other PAs (gardening) (PA type 3). These physical activities were categorized according to the first original article [21], the aim of which was to explore the emotional state of participants and if different types of PA could play moderate emotional state, for example, PA type 1 could reduce depressive states [16]; PA type 2 reduced anxiety [18]; and PA type 3, could do both and also increase life satisfaction [22].

Several studies have demonstrated the positive impact of high-intensity and medium-intensity sports activity on physical and mental health outcomes [23,24,25,26,27]. High-intensity interval training (HIIT) in adolescents (n = 65; mean age = 15.8 ± 0.6 years) for 8 weeks showed improved mean feeling state scores and psychological well-being (in the aerobic group there were small improvements in executive function (mean change (95% CI) -6.69 (-22.03, 8.64), d = -0.32) and psychological well-being (mean change (95% CI) 2.81 (-2.06, 7.68), d = 0.34)) [23], can reduce ill-being in children and adolescents, and may also enhance self-efficacy (22 studies, small to moderate effects were found for executive function (standardized mean difference [SMD], 0.50, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.03-0.98; P = 0.038) and affect (SMD, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.05-0.62; P = 0.020), respectively) [24], and can help reduce anxiety and depression [25]. HIIT improved cardiorespiratory fitness, anthropometric measures, blood glucose and glycaemic control, arterial compliance and vascular function, cardiac function, heart rate, exercise capacity, increased muscle mass, and reduced inflammatory markers compared to non-active controls [25]. Both aerobic training and strength/flexibility training appear equally effective for treating depressive and anxiety symptoms [27]. Light to moderate physical activity that is performed regularly seems to be associated with a more favorable mental health pattern compared with physical inactivity (n=177, 49% male, mean age - 39) [28].

This type of activity (medium-to high intensity) has also been shown to have positive effects on the BMI reduction (25 articles, single-component (84%) or a hybrid-type, multi-component (16%) HIIT protocol and involving 930 participants) [26]. For high-intensity sports, the reviewed studies suggest that participation in sport is associated with higher levels of alcohol consumption, but lower levels of cigarette smoking and illegal drug use (based on 34 peer-reviewed studies) [29].

Several studies have also showed the positive role of low-to-moderate-intensity physical activity (e.g. yoga, Tai-Chi, stretching, Pilates, etc.) for physical [30] and mental health [31] outcomes. In a study involving participants with chronic major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder, the inclusion of 11 weeks of hatha yoga classes in their therapy showed a significant reduction in depression and anxiety scales (n=14, median depression scales decreased by 38% and median anxiety scales decreased by 50%) [32]. Additionally, the positive effects of this type of activity, specifically Thai Yoga, have been demonstrated in overweight/obese older women [33].

In our study, PA type 3 is related to outdoor leisure group sport and other PA (gardening). It is generally noted that low-intensity physical activity is more common among older adults [34,35]. In the work of Takiguchi et al. [34] a relationship was shown between leisure activities and reduction of depression when resilience played role as a mediator (n=300, Japanese participants). In a study by Sala et al (n=809, age – 72-74, Japanese), engaging in leisure activities was positively associated with all three indicators of successful aging: preservation of cognitive function, physical function, and mental health [35]. Several studies have shown a positive correlation between leisure activities and various aspects of mental health and well-being. Ponde & Santana (n=552, Brazil) [36] demonstrated that participation in leisure activities may help maintain mental health under adverse life conditions. In a study by Müllersdor et al. (n=39 995, Swedish participants) [37], a positive correlation was shown between pet ownership and leisure activities (interest in nature and gardening), pet owners also showed better overall health than those without pets. However, these individuals were more likely to suffer from mental disorders than non-pet owners. An inverse relationship between leisure activity and general practitioner (GP) visits was demonstrated in a study by Martin et al. (n = 1000, 75.32 +/- 6.72 years old) [38]. Several studies have shown that more active older adults demonstrate better health outcomes and are less likely to visit doctors [39,40,41]. Fisher et al. [39] examined the relationship between leisure time physical activity and health services utilization (n=56 652, Canadian, 48% male; mean age 63.5 ± 10.2 years). They showed that active 50-65-year-old individuals were 27% less likely to report any GP consultations (ORadj = 0.73; P < 0.001) and had 8% fewer GP consultations annually (IRRadj = 0.92; P < 0.01) than their inactive peers.

Several studies have demonstrated the role of time spent outdoors and physical activity in promoting mental health [42,43,44,45,46]. Such physical activity impacted self-esteem, self-motivation, willpower, and readiness to solve complex tasks [47,48,49]. In a study by Jackson et al. (N = 624, ages 10–18, United States) [50], it was shown that adolescents who engaged in outdoor activity more frequently reported less decline in subjective well-being during the COVID-19 Pandemic, indicating the important role of being outdoors in increasing resilience to stress.

In a study by Johnson et al [51], a six-week intervention involving outdoor exercise resulted in average decreases in body weight (-1.08%) and fat percentage (-7.58%) compared to baseline measures. In a cohort study by Cleland et al, adolescents who spent more time outdoors had 27-41% lower rates of obesity. Similarly, Deforche et al [52] also demonstrated the positive role of physical activity in reducing obesity among adolescents.

Smoking alone is related to a range of health problems, including mood and anxiety disorders [1], earlier aging and death [6]. Along with physical activity it is seen as one of the most important lifestyle factors in terms of preventing chronic diseases [6,9]. The interdependence of smoking and physical activity is controversial.

Martinez-Gonzalez et al. [53] showed that higher levels of education were positively associated with a greater tendency to increase leisure-time physical activity for both men and women. The authors also revealed an inverse relationship between body mass index and low-intensity physical activity. Kim et al [54] revealed that higher life satisfaction was associated with fewer doctor’s visits, and that factors such as physical activity may influence increased life satisfaction. A positive association between physical activity and fewer visits to doctors was also confirmed in Kim et al. [54].

A face-to-face interview of 16,230 respondents was conducted by Eurobarometer in 2002 [53] to access physical activity in the 15 member states of the European Union. It was revealed that different European countries differ greatly in the level and nature of physical activity. Finland was the most active (92%), while Portugal was the least active (41%). Belgium occupied a middle position (62%) [53]. European countries also differed greatly in other indicators, such as days of vigorous and moderate physical activity, days of walking, and metabolic equivalence estimates [55]. Hence, it is more fitting to scrutinize epidemiological data that pertains to a specific country, rather than relying on a broad European sample. This study, for instance, focuses on analyzing the epidemiological data of the Belgian population.

This study's main strengths were having a large representative sample from the general population and simple categories defining physical activity, making them easier for the public to identify. Our findings add experimental evidence in support of extant research [56] to suggest a positive influence of physical activity on reducing the frequency of doctor’s visits. This data is needed to better tailor further interventions. It is important to know more about the association between healthy lifestyle behaviors and physical activity in order to better formulate public health strategies. The novelty of this study is in the investigation of the relationships of frequency of different types of physical activities with public health (physical and mental). The preliminary results of this study were presented at the ISEE (International Society for Environmental Epidemiology) conference [57].

1.1. General aim of this study:

To investigate if the frequency of practicing three different types of physical activity (PA) (dependent variables) is associated with healthy life styles, consumption habits (smoking and alcohol), BMI, level of study, age, sex and the number of visits of all doctors (except of psychiatrists) and psychiatrists (physical and mental health indicators), obtained retrospectively from the health registries of the 10 years preceding the rest of data collection (independent variables).

1.2. Main hypotheses:

A higher frequency PA type 1 (H1), type 2 (H2) and type 3 (H3) is positively associated with:

1.2.1. Health indicators:

a) better physical health (namely with a lower number visits to all doctors except psychiatrists);

b) better mental health (with less visits to psychiatrists);

1.2.2. Healthy life style:

c) lower BMI;

d) higher alcohol consumption, and

e) less tobacco consumption.

Additionally, we would like to explore the associations of the frequency of engaging in the three types of PA with age and sex due to contradictory data in the literature.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and original data collections

This is a study with cross-sectional design, though we did use some dataset from health registries collected longitudinally (records of numbers of all doctor’s visits and visits to psychiatrists were summed over the 10 years preceding the study) [21]. This study was based on the general Belgian population with 10,661 participants (see Annex I for the flow chart of the samples from the original and current studies). The final dataset for analysis consisted of 9,617 (aged from 19 to 81 years old; M=56.5, SD=14, 59% female) after merging those who replied on the Survey (PA and healthy life style) with the available health records.

The study [21] received approval from the Ethical Committee of the Psychological Science Department and from the collaborative entity Mutualité Chrétienne-Christelijke Mutualiteit (MC-CM), the law service of the Mutual Benefity Society and their financial and organizational help. All respondents received detailed information about the study and the data processing and provided separate written consent for the questionnaire study and the coupling of their answers with their medical records in possession of the MC-CM. Only people who provided written consent for both parts were included in the study. The realization of this study (planning of the hypothesis and data analysis) was supported by the MC-CM, by the 2012 Belgian-American Education Foundation (BAEF) alumni award granted to M.M. The MC-CM helped with data collection by providing us with the email address of their members and by providing us with the health records of people with whose consent we coupled their answers with their health records. None of funding providers had any role in the data analyses and interpretation, nor had they any right to approve or disapprove the writing and publication of the manuscript. The previous publicaitons on this study cover the main research question [21], and complementary research was performed in 2017 and presented in the international conference in 2018 [57].

2.2. Study design and variables

The demographic data (age, sex, level of studies) and epidemiological data such as indicators of physical (the sum of numbers (N) of visits to GPs and all doctors except psychiatrists) and mental health (the sum of numbers (N) of visits of psychiatrists) over the 10 years preceding the original study [21]. Other health and healthy life style factors such as BMI, smoking and alcohol consumption habits were collected together with the questionnaire about doing the three types of physical activities: 1 - sport – medium to high intensity exercises as aerobics, running, biking, swimming, Nordic walking, etc.; 2 – stretching exercises of yoga type – yoga, Tai-Chi, Pilates, etc. and 3 – outdoor leisure group sports and other PAs (gardening) (see Annex 2 & 3 for more details).

2.3. Data analysis

The descriptive statistics and multinomial logistic regression analysis were performed using STATA v.14. The outcome variables were the frequencies of practicing the three types of PA and the independent variables were the indicators health and healthy life style such BMI, consumption habits and the sum of the number of visits to all doctors (except of psychiatrists) as an indicator of physical health, and visits to psychiatrists as an indicator of mental health), and socio-demographic variables (age, sex and level of studies). The frequencies of practicing the three types of PA, substance consumption and level of studies were categorized before data collection (Annex 2.1.). For the variables that were not categorized during the data collection as per the designed Survey, such as age, BMI, and the sum of visits to psychiatrists we used the categories represented in Annex 2.2 and Table 1. For the variable for physical health indicator - the sum of all doctor’s visits (except psychiatrists), we used a 25% quartile distribution (Table 1).

3. Results

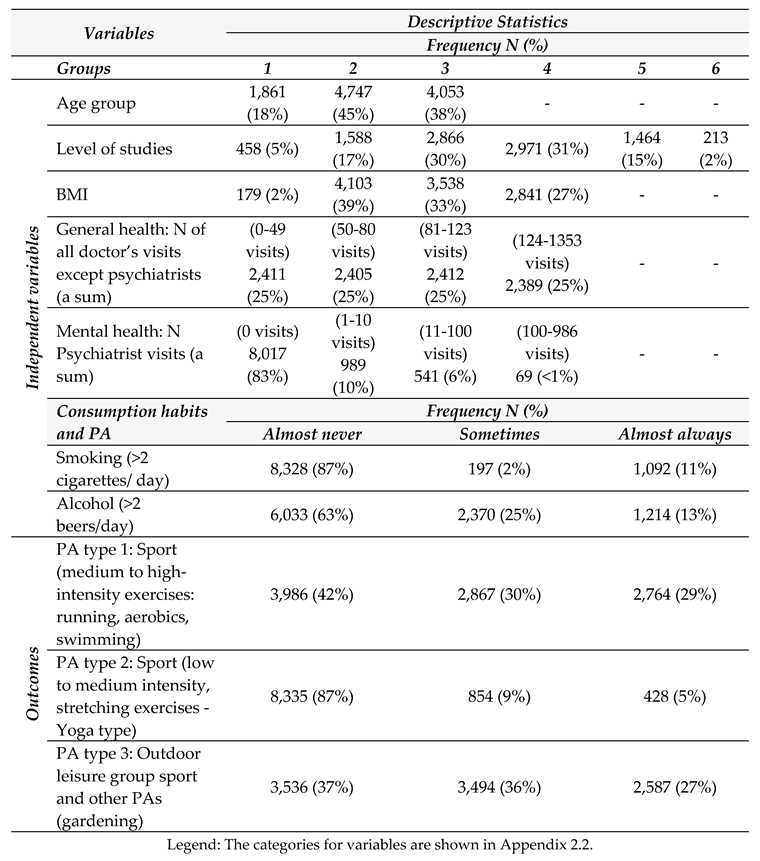

The descriptive statistics of the study variables are presented in Table 1.

The descriptive statistics for sex subgroups are represented in Annex 3 (Table A3.1 for women, Table A3.2 for men). All study variables differed for both sex subgroups at a statistically significant level p<.001 (except PA type 1 -intensive to medium sport exercises-, where the p-value was .015, but also significant) measured as per bivariate analysis (chi-square).

Multinomial logistic regression analysis was performed in order to observe where (and in which magnitude) a significant relationship between the three types of physical activities and observed variables of a healthy life style (BMI, health indicators and substance consumption habits – smoking and alcohol) exists. For general (physical) health indicators, the sum of the number of all doctor’s visits, except psychiatrists and for mental health, the sum of number of visits to psychiatrists from the clinical histories were used as proxies. The results, expressed in terms of Relative Risk Ratios (RRR) and 95% confident intervals (CI), are shown for the total group, and for women and men analyses for each type of physical activity: PA type 1 – Table 2; PA type 2 – Table 3; and PA type 3 – Table 4.

Additional regression analysis also showed that the physical health indicators of the participants of this study have a statistically significant (p<.05) direct relationship with their age and an inverse relationship with the level of education. In contrast, mental health indicators have a statistically significant (p<.05) inverse relationship with the age of the participants and a direct relationship with the level of education.

Age was directly associated at the statistically significant level with practicing PA type 1 only in women (Table 2), meaning that with increasing age, more frequent engagement in such physical activities was reported by the study participants. Men were more prone to practice such sport activities at the “almost always” level compared to women due to direct relationship between variable sex (men were coded with a higher number, see Annex 2) compared to women (Table 2). BMI was reversely associated with practicing PA type 1 (more frequent practicing– lower BMI) (Table 2).

Level of study played a significant relationship with PA type 1, indicating the direct relationship between level of study and the frequency of practicing PA type 1 (Table 2).

A higher frequency of all doctors’ visits except psychiatrists (indicator of physical health) was significantly associated with less frequent practice of PA type 1. A weaker and inverse relationship was shown with the frequency of psychiatrist visits (indicator of mental health) with this PA. In the reverse direction, higher frequency of РА type 1 was associated with higher physical health indicators (i.e., fewer visits to doctors except psychiatrists) and higher mental health scores (i.e., fewer visits to psychiatrists), but only at the level of group values if compare “almost always” with a baseline – “almost never” (p=.046) (Table 2).

As for consumption habits, more frequent smoking was associated with less frequent PA type 1; whereas no significant relationship was observed with alcohol consumption, on the exception of a weak direct relationship (more frequent alcohol consumption was associated with more frequent practicing PA type 1) observed in women (RRR=1.12; p=.045) (Table 2).

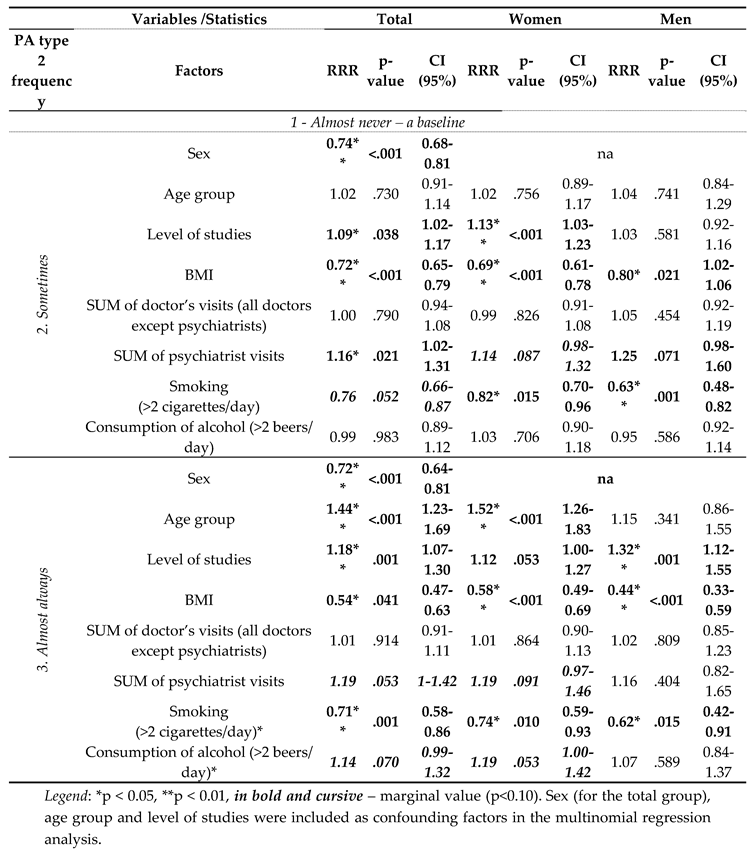

Similar to the PA type 1 results, the trends in BMI (reverse); age, and educational level (direct) were observed in the relationship with physical activity type 2 -Sport (stretching exercises, low to medium intensity - Yoga type) (Table 3). The sex variable showed the inverse to the frequency of PA type 1 association, indicating more frequent practice in women compared to men (Table 3).

A weak relationship with the indicator of mental health (sum of number of visits to psychiatrists) was observed at the whole group level when comparing “sometimes” practicing PA type 2 to baseline or “almost never”. When split by sex subgroups this relationship was shown at marginal p-levels (p<.10) (Table 3). More frequent smoking was associated with less frequent practicing of stretching and relaxation exercises in both men and women (Table 3).

Finally, for PA type 3 - Outdoor leisure group sport and other physical activities (gardening) showed similar trends to PA type 1 in the relationship with sex (men were more prone to practice it more frequently); age and educational level (direct: with higher age, more frequent practice and reverse relationships with BMI and smoking (Table 4).

Both proxies of general and mental health indicators are associated with higher frequencies of practicing PA type 3 since a reverse relationship is observed between N of doctors’ visits and frequency of practice for the whole group, as well as separately for men and women (Tables 4).

As per the factors role association in our study, we found that a higher frequency of practicing PA type 1 was primarily linked to lower BMI (a protective factor; 47% probability of occurrence if practicing “almost always” and 24% for “sometimes” compared to the baseline – “almost never” practicing) and less or non-smoking behavior (a protective factor; 41% probability of occurrence with practicing “almost always” and 29% for “sometimes” compared to the baseline – “almost never”). Other important factors included having a higher level of education (a protective factor; 14% and 7% probability of occurrence with practicing “almost always” and “sometimes” respectively), and better physical health (measured by the number of all doctor’s visits, excluding psychiatrists) (a risk factor, 13% and 9% of occurrence for the categories with practicing PA 1 “almost always” and “sometimes”); mental health, expressed inversely by the sum of the number of visits to psychiatrists (a risk factor, 9% of occurrence of having more visits and only significant with practicing PA type 1 “almost always vs. the baseline “almost never”); higher alcohol consumption (7% occurrence, but it had a marginal association (p<0.10) for the whole group and practicing “almost always“, and was significant only in the women subgroup for the “almost always” category) (Table 2).

A higher frequency of type 3 PA was also found to be associated with similar factors, firstly, a greater likelihood of a lower BMI, the second most significant factor was older age, the 3rd most significant factor was non-smoking behavior, and the fourth most significant factor was physical and mental health (Table 4).

Frequency of PA type 2 was not found to be associated with physical health, but positively correlated with poor mental health (Table 3). Moreover, while men showed a greater preference for practicing PA type 3 and 1 more than women, women showed a greater trend to practice PA type 2 more frequently (Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4).

4. Discussion

4.1. General Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first large scale study reporting the frequency of practicing of three different types of PA at population level linked to healthy life styles (BMI, smoking and alcohol consumption habits), indicators of physical health (the number visits of all doctors except psychiatrists) and mental health (visits to psychiatrists) taking into account age and level of studies and with a split analysis by sex groups. The majority of previous studies reported only on statistically significant associations of changes in increasing PA related to increasing only physical health [58]. Since our study had a transversal design, the observed associations do not represent the casual relationship between outcomes and independent factors. Thus it there could be inverse or bidirectional possible cause-effects relationships and the results should be interpreted carefully. For example, if people have very poor physical and/or mental health, it might be more difficult for them to practice any type of physical activity at all.

Our study both confirms and expands upon the existing literature, while also highlighting some discrepancies that require further investigation. Specifically, our findings support the notion that moderate to high intensity physical activity is associated with lower BMI, non-smoking behavior, higher education, and better physical and mental health, consistent with previous research [16,23,24,25,26,29,33,53,59]. However, no statistically significant associations were found for alcohol (only at a marginal level), this contradicts the literature data [29].

Additionally, our results suggested that men may have a greater preference for PA type 1 than women, which aligns with previous studies indicating higher rates of regular physical activity among men [60]. Furthermore, our study highlights potential sex differences in motivational factors for exercise, with men focusing more on intrinsic factors (strength, competition, and challenge) and women on extrinsic factors (weight management and appearance) [61] and mental health, as shown by our study results. Men, with higher intrinsic motivation, are more likely to maintain regular physical activity throughout their lives, while women tend to engage in physical activity more regularly as they age, which may be accompanied by gradual weight gain [62]. This could explain why as women get older, they become more conscious of their health and the importance of maintaining a healthy lifestyle, which is also reflected in their regular engagement in physical activity.

As per our study results, a higher frequency of PA2 is associated with more psychiatrist visits that could be related to the fact that healthcare professionals endorse this type of exercise to maintain or prevent problems with mental health. These findings contradict existing literature that demonstrates a direct association between this type of physical activity and both physical [30] and mental health [31] outcomes. Previous studies have shown that yoga can reduce the symptoms of depression and anxiety [32]. Hence, psychiatrists may recommend engaging in this activity to enhance psychological well-being. If the health becomes poorer and requires more attention to maintain it, doctors might prescribe more exercise due to the scientific evidence found on improving mental health (specifically, depression) by doing mild exercise [10,15,27,63,64,65]. And this fact could be one of the possible explanations of the positive relationship we observed in our study between practicing mild to medium intensity stretching and relaxation activities (PA type 2 - Yoga, Pilatus and Tai-chi) “sometimes” compared to the baseline “almost never” with poorer mental health (higher numbers of visits of psychiatrists). It would not mean in this case the opposite: that practicing these types of sport would increase the number of visit of doctors in the general population but indicates that in our study we had participants who practiced this type of PA (type 2) with poorer mental health and did it possibly to improve or to maintain their mental health. They were either prescribed by doctors to practice it or they themselves decided to practice since the level of education was also found as an important factor related to higher frequency of practicing all PAs.

The frequency of engaging in PA type 1 and PA type 3 had an inverse relationship with physical health indicators (number of visits to doctors, excluding psychiatrists) and mental health indicators (visits to psychiatrists) - individuals who practiced these types of physical activity more frequently tended to have fewer doctor visits. This finding aligns with the existing literature.

Age is more related with frequency of practicing PA type 1 & 3 in women as shown by the results of our study. Men only showed significance to age when practicing PA type 3 in the category “almost always”. This is probably due to a more conscious approach to training and maintaining a healthy lifestyle. According to the literature data, the opposite trend is usually noted - a decrease in the overall level of physical activity with age [60]. For both sexes the relationship between higher age and PA was observed only for regular PA type 3 (leisure outdoor activities) that also could be related to retiring and having more time for it.

There are many contradictory data on the dynamics of physical activity with age. Generally, authors have noted a general tendency for physical activity levels to decrease with age [66]. Although other authors note the presence of an indirect linear decline in physical activity with age, which closer to old age may stabilize and even improve [60]. The tendencies to greater physical activity with age in women obtained in our study are consistent with the literature data [60,66].

Our findings suggest that individuals with higher levels of education are more likely to engage in all three types of physical activity. This could be attributed to their greater knowledge and awareness of the benefits of physical and mental health, as well as their potentially more favorable socio-economic status. Conversely, those with lower SES may experience more stress and have less stress resilience, which may impact their ability to engage in physical activity [67]. These results align with a previous Eurobarometer study, which found that higher education levels were associated with increased physical activity among Europeans [68].

Our findings can be interpreted within the following framework. A higher level of education may indicate a more conscientious approach to life, including taking control of one's health and maintaining a healthy lifestyle. This is supported by the association between the frequency of practicing all three types of physical activity (PA type 1,2,3) and a higher level of education, as well as lower BMI and reduced tobacco consumption. Furthermore, the age factor plays a more prominent role in regular engagement in PA type 2 for women and PA type 3 for men. There are few studies on sex differences in the preference for different types of physical activity. Peral-Suárez et all. [69] (364, 154 male, Spanish schoolchildren) showed, that time spent in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity was significantly lower for girls compared to boys (1.44 ± 0.07 vs. 1.46 ± 0.07, p < 0.001 and 0.74 ± 0.40 h/day vs. 0.90 ± 0.45 h/day; p < 0.001, respectively). Dancing, rhythmic gymnastics, skating, and water sports were practiced more by girls, while football, wrestling sports, handball, and racket sports were practiced more by boys (p < 0.05).

Our findings revealed a negative link between the frequency of practicing different PAs and smoking behavior, providing support for hypotheses H1e, H2e, and H3e. However, no significant association was observed with alcohol consumption, thereby failing to confirm hypothesis H1d, H2d, and H3d. These results partially contradict our previous pilot study conducted on the same cohort [21,57], as well as Henchoz's findings [4], where a positive relationship between alcohol consumption and sport participation is sometimes interpreted as a factor of "socialization" with others.

Henchoz et al. [4] citing other authors mention that sport activity (incl. regular sport activity, everyday physical activities during work, leisure time, housework and travel) was shown to have a negative correlation with smoking and positive with alcohol use. They discovered a similar result: all sorts of physical activity were associated with at-risk use of alcohol, and all sorts of physical activity apart from sport and exercise are associated with at-risk use of cigarettes and cannabis [4]. In their paper Maertl et al [70] showed a positive relationship between regular light physical activity and a higher level of education, good coping behaviour, regular alcohol consumption, and being satisfied with life. The longitudinal study by Paavola et al [71] examined the associations among smoking, alcohol use, and physical activity, and aimed to assess how the health behaviors predicted changes in other health behaviors from adolescence to adulthood. The prevalence of leisure-time physical activity did not change significantly over time. Smoking and alcohol use positively correlated in each study. Smoking negatively correlated with leisure time physical activity. The best predictors for each healthy behavior were the same behaviors measured previously, but smoking had the strongest level of continuity. In our study, the age of the sample ranged from 19 to 81. Thus, the habit of smoking apparently formed earlier, during adolescence.

Some studies have found positive associations between alcohol consumption and physical activity [72]. Some analyzed the positive aspects of moderate alcohol consumption. For example, Peele & Brodsky [73] analyze the positive psychological concomitants of moderate alcohol consumption: subjective health, mood enhancement, stress reduction, sociability, social integration, mental health, long-term cognitive functioning, and work income/disability. In a systematic review by Dodge et all [74] it was shown that nearly 88% of the studies with college students and 75% of studies with nonstudent adults reported a positive relationship between physical activity and alcohol use. Physical activity is a crucial factor in promoting good health; however, numerous studies emphasize a concerning correlation between high levels of regular physical activity and escalated alcohol consumption in society. This poses a significant challenge as excessive alcohol intake poses a grave risk to public health.

Our findings, in general, do not support previous studies that have reported a direct association between high-intensity exercise and alcohol consumption [26,29] though we explored more on the frequency level practice. At the whole group level, our study did not find any significant relationship between the frequency of engaging in all three types of physical activity and alcohol consumption. In our study, the only significant positive associations were found for the female subgroup in PA type 1 only in the category “almost always”, which may be attributed to the social aspect of alcohol consumption among women who regularly engage in sports and follow a healthy lifestyle. These results indicate the need for further investigation and exploration of these associations.

4.2. Study Limitations

One of the limitations of this study is the slightly higher percentage of women in the sample (59%) that could lead to the general results being slightly biased by sex. Another study limitation consists of the transversal design for the Survey on sport activities and smoking and alcohol consumption habits that does not presume any existing causality and we report only the existing relationship between the variables of the study. To check this, longitudinal studies would help.

Another study limitation is that we used the sum of all doctor visits as a proxy indicator of physical health. This metric may not always provide an accurate reflection of an individual's overall health status, as some individuals may visit doctors frequently for preventative care. Furthermore, younger participants may be less likely to visit doctors compared to their older counterparts. An additional limitation of the study is the reliance on self-reporting for assessing indicators of physical and mental health. This subjective measurement approach may introduce potential bias, as individuals might misrepresent or inaccurately report these parameters.

Finally, since it was a secondary data analysis on data collected for the exploration of emotions and emotional intelligence behavior among the Belgian population [21], the initial classification of types of PAs was designed more in line with the initial purpose and we could not change it. Nevertheless, this classification helps to distinguish and see the differences in the relationship of frequency of practicing of PA type 2 with mental health (the sum of visits to psychiatrists) compared to other types of PAs.

4.3. Practical Implications

The results highlight the importance of promoting healthy lifestyles and physical activity across different segments of society, including those with lower levels of education. Initiatives should start during adolescence, as the literature suggests that overall physical activity levels tend to decline during this period.

Men appear to have an easier time maintaining regular (higher frequency) levels of moderate to high intensity physical activity, such as jogging or swimming, as well as engaging in leisure activities like outdoor group games. On the other hand, women tend to pay more significant attention to physical activity and healthy lifestyles as they age. Since frequency of practicing PA was related to higher age; it is important to promote and potentiate the PA engaging in earlier ages.

Additionally, the findings indicate that even mild to moderate leisure activities, such as group sports or gardening, are associated to better health and healthy life style. These activities are comparable, and in some cases even superior, in their association with the health indicators used in this study as proxies for overall health or healthcare needs.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we examined the association between frequency of practicing three types of physical activity and indicators of a healthy lifestyle (such as BMI, smoking, and alcohol consumption), physical health (measured by the number of doctor’s visits excluding psychiatrists), and mental health (measured by the number of visits to psychiatrists) across different age groups in men and women. In sum, as per results of our study, hypothesis H1 (higher frequency of practicing PA type 1) was significantly associated with the exposure factors described in sub-hypothesis: H1a (better physical health or a lower number of visits to all doctor’s), H1b (better mental health or a lower number of visits to psychiatrists), H1c (lower BMI), and H1e (less tobacco consumption); but not for sub-hypothesis H1d (alcohol consumption) where the relationship wasn’t significant. As for H2 (higher frequency of practicing PA type 2), there was no association with H2a (physical health), a positive relationship with poorer mental health (the inverse result of the initial hypothesis H2b and results for PA type 1 and 3), and sub-hypothesis H2c (lower BMI) and H2d (alcohol consumption, only on a marginal level, with a regular practice and in women) were confirmed. As for H3 (higher frequency of practicing PA type 3, the results were similar to those for H1.

The frequency of engaging in different types of physical activity can depend on our physical and mental health conditions. On one hand having these health conditions can be related with a possibility of practicing PA more frequently (especially type 1 and 3); but having poorer health may be an obstacle, or alternatively be a start point to maintain it and protect it from worsening later. The frequency in engaging in different types of PA depends also on sex, age and level of education.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.L., S.L, A.P.; methodology, S.L. and L.L.; formal analysis, L.L., A.P.; investigation, A.P., I.P. and L.L.; resources, S.L. and A.P.; data creation, A.P., I.P. and L.L.; writing—original draft preparation, I.P. and L.L.; writing—review and editing, S.L. and L.L.; visualization, I.P.; supervision, S.L. and L.L.; project administration, L.L.; funding acquisition, S.L. and L.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was supported by the Psychological Institute of the Russian Academy of Education.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study received approval from the Ethical Committee of the Psychological Science Department Nº 08/2014 dated 15/01/2014. The ethical issues of the original dataset were revised by the law department service of the collaborative entity Mutualité Chrétienne-Christelijke Mutualiteit (MC-CM) in 2009 acoording tho the Beligum laws and considering Helsinki Declaration. The dataset used was anonymous and without any vulnerable information.

Informed Consent Statement

All respondents received detailed information about the study and the data processing and provided separate written consent for the questionnaire study and the coupling of their answers with their medical records in possession of the MC-CM. Only people who provided written consent for both parts were included in the study.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Moira Mikolajczak for her critical comments and also support with data for this study, as well as to University of Louvain and the law department of the Mutualité Chrétienne-Christelijke Mutualiteit. We are thankful to David Jappy for the English correction.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Annex 1: Flowchart illustrating the study sample (in the original and current studies).

Annex 2: Questionnaire & Groups of variables

Annex 3: Descriptive statistics by sex groups:

Table A3.1.

Descriptive statistic for the study variables for women.

|

Table A3.2.

Descriptive statistics for the study variables for men.

|

References

- Moylan, S.; Eyre, H.A.; Maes, M.; Baune, B.T.; Jacka, F.N.; Berk, M. Exercising the Worry Away: How Inflammation, Oxidative and Nitrogen Stress Mediates the Beneficial Effect of Physical Activity on Anxiety Disorder Symptoms and Behaviours. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2013, 37, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westerterp, K.R. Control of Energy Expenditure in Humans. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 71, 340–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ainsworth, B.E.; Watson, K.B.; Ridley, K.; Pfeiffer, K.A.; Herrmann, S.D.; Crouter, S.E.; McMurray, R.G.; Butte, N.F.; Bassett, D.R.; Trost, S.G.; et al. Utility of the Youth Compendium of Physical Activities. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2018, 89, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henchoz, Y.; Dupuis, M.; Deline, S.; Studer, J.; Baggio, S.; N’Goran, A.A.; Daeppen, J.-B.; Gmel, G. Associations of Physical Activity and Sport and Exercise with At-Risk Substance Use in Young Men: A Longitudinal Study. Prev. Med. 2014, 64, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katano, H.; Ohno, M.; Yamada, K. Protection by Physical Activity Against Deleterious Effect of Smoking on Carotid Intima-Media Thickness in Young Japanese. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2013, 22, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Södergren, M.; Wang, W.C.; Salmon, J.; Ball, K.; Crawford, D.; McNaughton, S.A. Predicting Healthy Lifestyle Patterns among Retirement Age Older Adults in the WELL Study: A Latent Class Analysis of Sex Differences. Maturitas 2014, 77, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinnafick, F.-E.; Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C. The Effect of the Physical Environment and Levels of Activity on Affective States. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conger, S.A.; Bassett, D.R. A Compendium of Energy Costs of Physical Activities for Individuals Who Use Manual Wheelchairs. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 2011, 28, 310–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2021). Physical Activity Fact Sheet (No. WHO/HEP/HPR/RUN/2021.2). World Health Organization.

- Biddle, S.J.H.; Asare, M. Physical Activity and Mental Health in Children and Adolescents: A Review of Reviews. Br. J. Sports Med. 2011, 45, 886–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuzum, H.; Stickel, A.; Corona, M.; Zeller, M.; Melrose, R.J.; Wilkins, S.S. Potential Benefits of Physical Activity in MCI and Dementia. Behav. Neurol. 2020, 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morres, I.D.; Hatzigeorgiadis, A.; Stathi, A.; Comoutos, N.; Arpin-Cribbie, C.; Krommidas, C.; Theodorakis, Y. Aerobic Exercise for Adult Patients with Major Depressive Disorder in Mental Health Services: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Depress. Anxiety 2019, 36, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, C.; O’ Sullivan, R.; Caserotti, P.; Tully, M.A. Consequences of Physical Inactivity in Older Adults: A Systematic Review of Reviews and Meta-analyses. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2020, 30, 816–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.-C.; Chao, C.-L.; Huang, M.-N. Psychological Effects of Physical Activity: A Quasi-Experiment in an Indigenous Community. Tzu Chi Med. J. 2014, 26, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota-Pereira, J.; Silverio, J.; Carvalho, S.; Ribeiro, J.C.; Fonte, D.; Ramos, J. Moderate Exercise Improves Depression Parameters in Treatment-Resistant Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2011, 45, 1005–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krogh, J.; Videbech, P.; Thomsen, C.; Gluud, C.; Nordentoft, M. DEMO-II Trial. Aerobic Exercise versus Stretching Exercise in Patients with Major Depression—A Randomised Clinical Trial. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e48316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinas, P.C.; Koutedakis, Y.; Flouris, A.D. Effects of Exercise and Physical Activity on Depression. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2011, 180, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero-Marín, J.; Asún, S.; Estrada-Marcén, N.; Romero, R.; Asún, R. Efectividad de un programa de estiramientos sobre los niveles de ansiedad de los trabajadores de una plataforma logística: un estudio controlado aleatorizado. Aten. Primaria 2013, 45, 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, G.W.; Silverman, D.H.S.; Siddarth, P.; Ercoli, L.M.; Miller, K.J.; Lavretsky, H.; Wright, B.C.; Bookheimer, S.Y.; Barrio, J.R.; Phelps, M.E. Effects of a 14-Day Healthy Longevity Lifestyle Program on Cognition and Brain Function. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2006, 14, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, J.; Gray, T.; Truong, S.; Sahlberg, P.; Bentsen, P.; Passy, R.; Ho, S.; Ward, K.; Cowper, R. A Systematic Review Protocol to Identify the Key Benefits and Efficacy of Nature-Based Learning in Outdoor Educational Settings. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikolajczak, M.; Avalosse, H.; Vancorenland, S.; Verniest, R.; Callens, M.; Van Broeck, N.; Fantini-Hauwel, C.; Mierop, A. A Nationally Representative Study of Emotional Competence and Health. Emotion 2015, 15, 653–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siefken, K.; Junge, A.; Laemmle, L. How Does Sport Affect Mental Health? An Investigation into the Relationship of Leisure-Time Physical Activity with Depression and Anxiety. Hum. Mov. 2019, 20, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costigan, S.A.; Eather, N.; Plotnikoff, R.C.; Hillman, C.H.; Lubans, D.R. High-Intensity Interval Training for Cognitive and Mental Health in Adolescents. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2016, 48, 1985–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leahy, A.A.; Mavilidi, M.F.; Smith, J.J.; Hillman, C.H.; Eather, N.; Barker, D.; Lubans, D.R. Review of High-Intensity Interval Training for Cognitive and Mental Health in Youth. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2020, 52, 2224–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martland, R.; Mondelli, V.; Gaughran, F.; Stubbs, B. Can High-Intensity Interval Training Improve Physical and Mental Health Outcomes? A Meta-Review of 33 Systematic Reviews across the Lifespan. J. Sports Sci. 2020, 38, 430–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batrakoulis, A.; Fatouros, I.G. Psychological Adaptations to High-Intensity Interval Training in Overweight and Obese Adults: A Topical Review. Sports 2022, 10, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paluska, S.A.; Schwenk, T.L. Physical Activity and Mental Health. Sports Med 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindwall, M.; Ljung, T.; Hadžibajramović, E.; Jonsdottir, I.H. Self-Reported Physical Activity and Aerobic Fitness Are Differently Related to Mental Health. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2012, 5, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisha, N.E.; Sussman, S. Relationship of High School and College Sports Participation with Alcohol, Tobacco, and Illicit Drug Use: A Review. Addict. Behav. 2010, 35, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanly, S.L.; Maniazhagu, D. Individual and Combined Interventions of Tai Chi, Pilates and Yogic Practices on Cardio Respiratory Endurance of b.Ed. Trainees. Int. J. Phys. Educ. Sports Manag. Yogic Sci. 2020, 10, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Liu, W.; Gao, S. Effects of Mind-Body Exercises on Cognitive Impairment in People with Parkinson’s Disease: A Mini-Review. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 931460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.J.; Remick, R.A.; Davis, J.C.; Vazirian, S.; Khan, K.M. Exercise as Medicine—the Use of Group Medical Visits to Promote Physical Activity and Treat Chronic Moderate Depression: A Preliminary 14-Week Pre–Post Study. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2015, 1, e000036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widjaja, W.; Wongwattanapong, T.; Laskin, J.J.; Ajjimaporn, A. Benefits of Thai Yoga on Physical Mobility and Lower Limb Muscle Strength in Overweight/Obese Older Women: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Trial. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2021, 43, 101345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takiguchi, Y.; Matsui, M.; Kikutani, M.; Ebina, K. The Relationship between Leisure Activities and Mental Health: The Impact of Resilience and COVID-19. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2023, 15, 133–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, G.; Jopp, D.; Gobet, F.; Ogawa, M.; Ishioka, Y.; Masui, Y.; Inagaki, H.; Nakagawa, T.; Yasumoto, S.; Ishizaki, T.; et al. The Impact of Leisure Activities on Older Adults’ Cognitive Function, Physical Function, and Mental Health. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0225006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pondé, M.P.; Santana, V.S. Participation in Leisure Activities: Is It a Protective Factor for Women’s Mental Health? J. Leis. Res. 2000, 32, 457–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müllersdorf, M.; Granström, F.; Sahlqvist, L.; Tillgren, P. Aspects of Health, Physical/Leisure Activities, Work and Socio-Demographics Associated with Pet Ownership in Sweden. Scand. J. Public Health 2010, 38, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.Y.; Powell, M.P.; Peel, C.; Zhu, S.; Allman, R. Leisure-Time Physical Activity and Health-Care Utilization in Older Adults. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2006, 14, 392–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, K.L.; Harrison, E.L.; Reeder, B.A.; Sari, N.; Chad, K.E. Is Self-Reported Physical Activity Participation Associated with Lower Health Services Utilization among Older Adults? Cross-Sectional Evidence from the Canadian Community Health Survey. J. Aging Res. 2015, 2015, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J.M.; Rottenberg, Y.; Cohen, A.; Stessman, J. Physical Activity and Health Service Utilization Among Older People. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2013, 14, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musich, S.; Wang, S.S.; Hawkins, K.; Greame, C. The Frequency and Health Benefits of Physical Activity for Older Adults. Popul. Health Manag. 2017, 20, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarta, S.; Levante, A.; García-Conesa, M.-T.; Lecciso, F.; Scoditti, E.; Carluccio, M.A.; Calabriso, N.; Damiano, F.; Santarpino, G.; Verri, T.; et al. Assessment of Subjective Well-Being in a Cohort of University Students and Staff Members: Association with Physical Activity and Outdoor Leisure Time during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 4787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashper, K.; King, J. The Outdoors as a Contested Leisure Terrain. Ann. Leis. Res. 2022, 25, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andre, E.K.; Williams, N.; Schwartz, F.; Bullard, C. Benefits of Campus Outdoor Recreation Programs: A Review of the Literature. J. Outdoor Recreat. Educ. Leadersh. 2017, 9, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandford, R.A.; Duncombe, R.; Armour, K.M. The Role of Physical Activity/Sport in Tackling Youth Disaffection and Anti-social Behaviour. Educ. Rev. 2008, 60, 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henstock, M.; Barker, K.; Knijnik, J. 2, 6, Heave! Sail Training’s Influence on the Development of Self-Concept and Social Networks and Their Impact on Engagement with Learning and Education. A Pilot Study. J. Outdoor Environ. Educ. 2013, 17, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornienko, D.S.; Rudnova, N.A. Exploring the Associations between Happiness, Lifesatisfaction, Anxiety, and Emotional Regulation among Adults during the Early Stage of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Russia. Psychol. Russ. State Art 2023, 16, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morosanova, V.I.; Bondarenko, I.N.; Fomina, T.G. Conscious Self-Regulation, Motivational Factors, and Personality Traits as Predictors of Students’ Academic Performance: A Linear Empirical Model. Psychol. Russ. State Art 2022, 170–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khlomov, K.D.; Bochaver, A.A.; Korneev, A.A. Well-Being and Coping with Stress Among Russian Adolescents in Different Educational Environments. Psychol. Russ. State Art 2021, 14, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.B.; Stevenson, K.T.; Larson, L.R.; Peterson, M.N.; Seekamp, E. Outdoor Activity Participation Improves Adolescents’ Mental Health and Well-Being during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halmstad University, Center of Research on Welfare, Health and Sport, Halmstad, Sweden; Johnson, U. ; Ivarsson, A.; Halmstad University, Center of Research on Welfare, Health and Sport, Halmstad, Sweden; Parker, J.; Halmstad University, Center of Research on Welfare, Health and Sport, Halmstad, Sweden; Andersen, M.B.; Halmstad University, Center of Research on Welfare, Health and Sport, Halmstad, Sweden; Svetoft, I.; Halmstad University, School of Business, Engineering and Science, Halmstad, Sweden Connection in the Fresh Air: A Study on the Benefits of Participation in an Electronic Tracking Outdoor Gym Exercise Programme. Montenegrin J. Sports Sci. Med. 2019, 8, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deforche, B.; Lefevre, J.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Hills, A.P.; Duquet, W.; Bouckaert, J. Physical Fitness and Physical Activity in Obese and Nonobese Flemish Youth. Obes. Res. 2003, 11, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angel Mart??Nez-Gonz??Lez, M.; Javier Varo, J.; Luis Santos, J.; De Irala, J.; Gibney, M.; Kearney, J.; Alfredo Mart??Nez, J. Prevalence of Physical Activity during Leisure Time in the European Union: Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2001, 1142–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.S.; Park, N.; Sun, J.K.; Smith, J.; Peterson, C. Life Satisfaction and Frequency of Doctor Visits. Psychosom. Med. 2014, 76, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Omar, K.; Rütten, A. Relation of Leisure Time, Occupational, Domestic, and Commuting Physical Activity to Health Indicators in Europe. Prev. Med. 2008, 47, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, D.E.; Mainous, A.G.; Carnemolla, M.; Everett, C.J. Adherence to Healthy Lifestyle Habits in US Adults, 1988-2006. Am. J. Med. 2009, 122, 528–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liutsko, L.; Mikolajczak, M.; Veraksa, A.; Leonov, S. OP VIII – 4 Type of Physical Activity, Diet, Bmi and Tobacco/Alcohol Consumption Relationship: Which of Them Affect More Our Health? In Proceedings of the Green, physical activity, mobility; BMJ Publishing Group Ltd, March 2018; p. A16.1-A16. [Google Scholar]

- Holstila, A.; Mänty, M.; Rahkonen, O.; Lahelma, E.; Lahti, J. Changes in Leisure-Time Physical Activity and Physical and Mental Health Functioning: A Follow-up Study. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2017, 27, 1785–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guddal, M.H.; Stensland, S.Ø.; Småstuen, M.C.; Johnsen, M.B.; Zwart, J.-A.; Storheim, K. Physical Activity and Sport Participation among Adolescents: Associations with Mental Health in Different Age Groups. Results from the Young-HUNT Study: A Cross-Sectional Survey. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e028555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, M.; Stull, T.; Claussen, M.C. Prevention and Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders through Physical Activity, Exercise, and Sport. Sports Psychiatry 2022, 1, 85–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancassiani, F.; Machado, S.; Preti, A. Physical Activity, Exercise and Sport Programs as Effective Therapeutic Tools in Psychosocial Rehabilitation. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2018, 14, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspersen, C. J. , Pereira, M. A., & Curran, K. M. Changes in Physical Activity Patterns in the United States, by Sex and Cross-Sectional Age. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 2000, 32, 1601–1609. [Google Scholar]

- Egli, T.; Bland, H.W.; Melton, B.F.; Czech, D.R. Influence of Age, Sex, and Race on College Students’ Exercise Motivation of Physical Activity. J. Am. Coll. Health 2011, 59, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, I.-M. Physical Activity and Weight Gain Prevention. JAMA 2010, 303, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallo, L.C.; Matthews, K.A. Understanding the Association between Socioeconomic Status and Physical Health: Do Negative Emotions Play a Role? Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 10–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerovasili, V.; Agaku, I.T.; Vardavas, C.I.; Filippidis, F.T. Levels of Physical Activity among Adults 18–64 Years Old in 28 European Countries. Prev. Med. 2015, 81, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maertl, T.; De Bock, F.; Huebl, L.; Oberhauser, C.; Coenen, M.; Jung-Sievers, C. ; on behalf of the COSMO Study Team Physical Activity during COVID-19 in German Adults: Analyses in the COVID-19 Snapshot Monitoring Study (COSMO). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paavola, M.; Vartiainen, E.; Haukkala, A. Smoking, Alcohol Use, and Physical Activity: A 13-Year Longitudinal Study Ranging from Adolescence into Adulthood. J. Adolesc. Health 2004, 35, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piazza-Gardner, A.K.; Barry, A.E. Examining Physical Activity Levels and Alcohol Consumption: Are People Who Drink More Active? Am. J. Health Promot. 2012, 26, e95–e104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peele, S.; Brodsky, A. Exploring Psychological Benefits Associated with Moderate Alcohol Use: A Necessary Corrective to Assessments of Drinking Outcomes? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000, 60, 221–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodge, T.; Clarke, P.; Dwan, R. The Relationship Between Physical Activity and Alcohol Use Among Adults in the United States: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Am. J. Health Promot. 2017, 31, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J. F. Age-Related Decline in Physical Activity: A Synthesis of Human and Animal Studies. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 2000, 32, 1598–1600. [Google Scholar]

- Peral-Suárez, Á.; Cuadrado-Soto, E.; Perea, J.M.; Navia, B.; López-Sobaler, A.M.; Ortega, R.M. Physical Activity Practice and Sports Preferences in a Group of Spanish Schoolchildren Depending on Sex and Parental Care: A Gender Perspective. BMC Pediatr. 2020, 20, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for the study variables.

|

Table 2.

Multinomial logistic regression analysis (RRR – relative risk ratios): PA type 1 (Sport of medium to high intensity: running, aerobics, swimming) with the study factors.

Table 2.

Multinomial logistic regression analysis (RRR – relative risk ratios): PA type 1 (Sport of medium to high intensity: running, aerobics, swimming) with the study factors.

|

Table 3.

Multinomial logistic regression analysis (RRR – relative risk ratios): PA type 2 (Stretching exercises, low to medium intensity - Yoga type) with the study factors.

Table 3.

Multinomial logistic regression analysis (RRR – relative risk ratios): PA type 2 (Stretching exercises, low to medium intensity - Yoga type) with the study factors.

|

Table 4.

Multinomial logistic regression analysis (RRR – relative risk ratios): PA type 3 (Outdoor leisure group sport and other physical activities (gardening)) with the study factors.

Table 4.

Multinomial logistic regression analysis (RRR – relative risk ratios): PA type 3 (Outdoor leisure group sport and other physical activities (gardening)) with the study factors.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Copyright: This open access article is published under a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license, which permit the free download, distribution, and reuse, provided that the author and preprint are cited in any reuse.

Is Frequency of Practice of Different Types of Physical Activity Associated with Health and a Healthy Lifestyle at Different Ages?

Liudmila Liutsko

et al.

,

2023

MDPI Initiatives

Important Links

© 2024 MDPI (Basel, Switzerland) unless otherwise stated