Preprint

Article

Impact of Plastic Pollution on Marine Biodiversity in Italy

Altmetrics

Downloads

139

Views

100

Comments

0

A peer-reviewed article of this preprint also exists.

This version is not peer-reviewed

Submitted:

21 November 2023

Posted:

22 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Alerts

Abstract

Abandoned, lost, or otherwise discarded fishing gear (ALDFG) is a primary contributor to the entanglement of numerous marine species. Utilizing digital media platforms like Google, Facebook, and Instagram we conducted an assessment of the detrimental effects of ALDFG and plastic litter, on the biodiversity of Italy's marine ecosystem. Our investigation revealed that plastic litter has adverse consequences on various forms of marine life, including reptiles, mammals, birds, fish, crustaceans, and mollusks, along different Italian geographical sub-areas. Several records of interaction between plastic and endangered and vulnerable marine species have been described. Our reports even highlight the impact on marine turtles, mainly on Caretta caretta. This is the first report of entangled with fishing nets in Cetorhinus maximus, Oblada melanura, Serranus scriba, Homarus gammarus, Octopus vulgaris, and Phoenicopterus roseus. Furthermore, we identified that ghost nets have repercussions for endangered and vulnerable marine species. This update sheds light on the ongoing adverse effects of ghost nets on the Italian marine ecosystem, yet it is crucial to acknowledge that the true extent of the problem remains underestimated.

Keywords:

Subject: Biology and Life Sciences - Aquatic Science

1. Introduction

Marine litter is becoming increasingly known as a major threat to marine wildlife. Plastics can constitute most of the marine litter, and they have become ubiquitous in ocean basins [1]. Plastics are known for their durability and low recycling rates, making them a persistent and pervasive problem in marine ecosystems, with profound implications for marine biodiversity [1]. The increasing accumulation of plastic waste in our seas is posing a grave threat to this delicate ecological balance [2]. The impact of plastic debris on marine fauna is growing in marine ecosystems, with adverse effects documented on over 900 species [3,4]. Abandoned, lost, or otherwise discarded fishing gear (hereafter ALDFG) is a major threat to marine biodiversity [5]. The presence of ALDFG frequently leads to ghost fishing, and is responsible for the entanglement of various organisms, including fish, birds, turtles, and mammals [6,7,8,9]. Entanglement refers to the interaction between marine life and anthropogenic debris that entraps animals or entangles their appendages within the loops and openings of the debris [10]. Examples of such items include strapping bands, ropes, or plastic bags that may encircle or create a loop around an animal [11], resulting in lacerations, mutilations, infections, and ultimately, mortality [12]. Furthermore, fragments of fishing nets and other plastic debris can be ingested by several marine animals [4,13]. Marine animals often mistake plastic fragments for a specific prey, and they may ingest plastic pieces that align with their anatomy and foraging strategy [14], such as plastic bags are mistaken by jellyfish from marine turtles [15].

The Mediterranean Sea is considered one of the most polluted areas by plastic [16,17]. This is worrying considering that the Mediterranean Sea is a hotspot for marine biodiversity hosting 4% to 18% of the world's marine species [18]. Italy, a country of south-central Europe, occupies a peninsula that juts deep into the Mediterranean Sea. With almost 8,000 km of coasts, the Italian waters are some of the Mediterranean’s most biodiverse, and host an estimated 14,000 marine species, of which 10% are unique to the area [18]. Until now 32 marine protected areas were established in Italy, with a covered surface of 57,181 km2 (10.1%) [19]. Italian coastal marine ecosystems are currently under great pressure from marine litter. The Italian coasts are characterized by a large presence of plastic debris on the seafloor at different depths, with accumulation zones reported in many different areas [20-26], as well as in sea surface and water column [27], and on the beaches [28-31]. In the last decade, many studies on plastic ingestion by marine mammals [32], reptiles [33], fish [34-36], shellfish [37, 38], and crustaceans [39] along the coasts of Italy were reported.

In this era of huge plastic production and consumption, it is crucial to understand the multifaceted impact of plastic on marine biodiversity, as well as the urgency of taking collective action to address this pressing problem [40]. Citizen science has emerged as a potent resource for gathering data on the presence of marine litter and its effects on marine biota [9, 41]. In this context, social media has evolved into a valuable tool for investigating the consequences of various activities on biodiversity, encompassing the influence of marine litter on marine biodiversity [9]. Over the past decade, information concerning the interaction between marine litter and marine in Italy was disseminated through digital and social media. This research aims to identify the species affected by marine litter and the hotspots of interaction between these species and marine litter along the Italian coast by the collection and analysis of data coming from digital and social media.

2. Materials and Methods

For this study, we selected the predominant digital and social media platforms in Italy, namely Google, Instagram, and Facebook. The authors used these platforms as data sources to investigate the effects of marine litter on marine biodiversity along the coasts of Italy. To conduct our search, we employed a set of combined keywords, including: “marine plastic + Italy”; “ghost fishing net + Italy”; “fishing net + marine animals”; “fishing net + entangled marine animals”; “ingestion of plastic + Italy”; fishing lines + marine animals + Italy; “entanglement + plastic + Italy”; “conservation + plastic + Italy”; stranding + marine animals + plastics, findings + marine animals + plastics, entanglement + marine fish + Italy; ingestion + marine fish+ Italy; entanglement + sharks+ Italy; ingestion + sharks+ Italy; entanglement +rays+ Italy; ingestion + rays+ Italy; entanglement + marine invertebrates+ Italy; ingestion + marine invertebrates + Italy; entanglement + marine turtles+ Italy; ingestion + marine turtles+ Italy; entanglement +seabirds+ Italy; ingestion + seabirds+ Italy; entanglement + cetaceans+ Italy and finally, ingestion + cetaceans+ Italy. We employed searches on Google, Instagram, and Facebook to identify pages associated with organizations or communities dedicated to marine pollution and conservation, and to find news in local newspapers. Every report was meticulously reviewed and documented in our database (Table S1, Supplementary Material). All reported species were recognized by photos and videos. The cases in which it was not possible to trace the species or have information on the place of discovery, date, and type of incident were discarded. We classified “ingestion” as the presence of material in the digestive tract and “entanglement” as the presence of material around or within a part of the body. For each record, we documented the species, the geographic location, the litter type, and the type of litter interaction. Additional information is shown in Table S1 (Supplementary Material). The species were identified using field guides and general morphological characteristics. In case of doubt about the identity of the species, photographs were sent to scientists for confirmation. We used specific literature to assess the conservation status of the species [42].

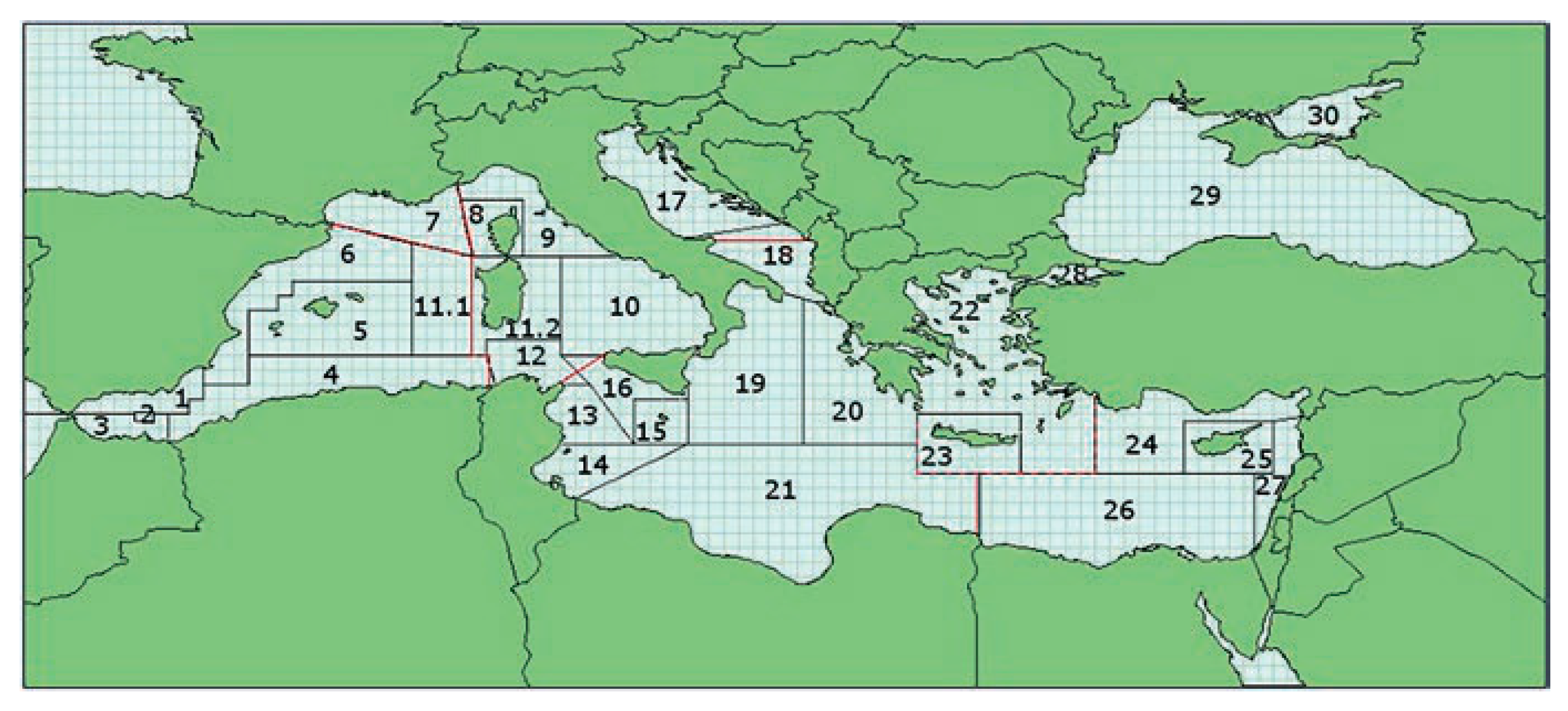

Additionally, data were analyzed considering the geographical subareas (GSAs) in which the report fell. The Italian GSAs recognized within the General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean framework are seven, namely GSA 9 – Ligurian and Northern Tyrrhenian Sea, 10 – Central and Southern Tyrrhenian Sea, GSA 11 – Sardinia, GSA 16 – Southern Sicily, GSA 17 - Northern Adriatic Sea, GSA 18 – Southern Adriatic Sea, GSA 19 – Western Ionian Sea (Figure 1). The Spearman test was applied to evaluate temporal trend of entanglement cases.

3. Results

The study conducted during the last fifteen years (2009 - 2023), showed that the major information source was Google (52%), followed by Facebook (32%), and Instagram (16%). A total of 127 cases involving interactions between marine species and marine litter were documented along the Italian coasts. A significant positive trend (rs= 0.88, p < 0.01) was observed starting from 1% in 2009 and reaching 24% by 2021 (Figure 2). Most of the cases were reported in autumn (38%), followed by summer (26%), spring (23%), and winter (13%).

Out of these recorded cases of interaction with marine litter, 16 distinct species were identified (the species are listed in Table S1 supplementary material). Our results showed that 61% of cases were entanglement and 39% of plastic ingestion. Additionally, a single record of concurrent entanglement and ingestion was observed. Marine turtles (78%) were the most affected marine animals, followed by cetaceans (9%), seabirds (5%), elasmobranchs (4%), teleost (2%), and invertebrates (2%) (Figure 3).

Marine turtles, Caretta caretta, Chelonia mydas, and Dermochelys coriacea, were the most impacted by plastics (Table S1). Among the three species reported, C. caretta was the most frequently recorded (94 records) (Figure 4).

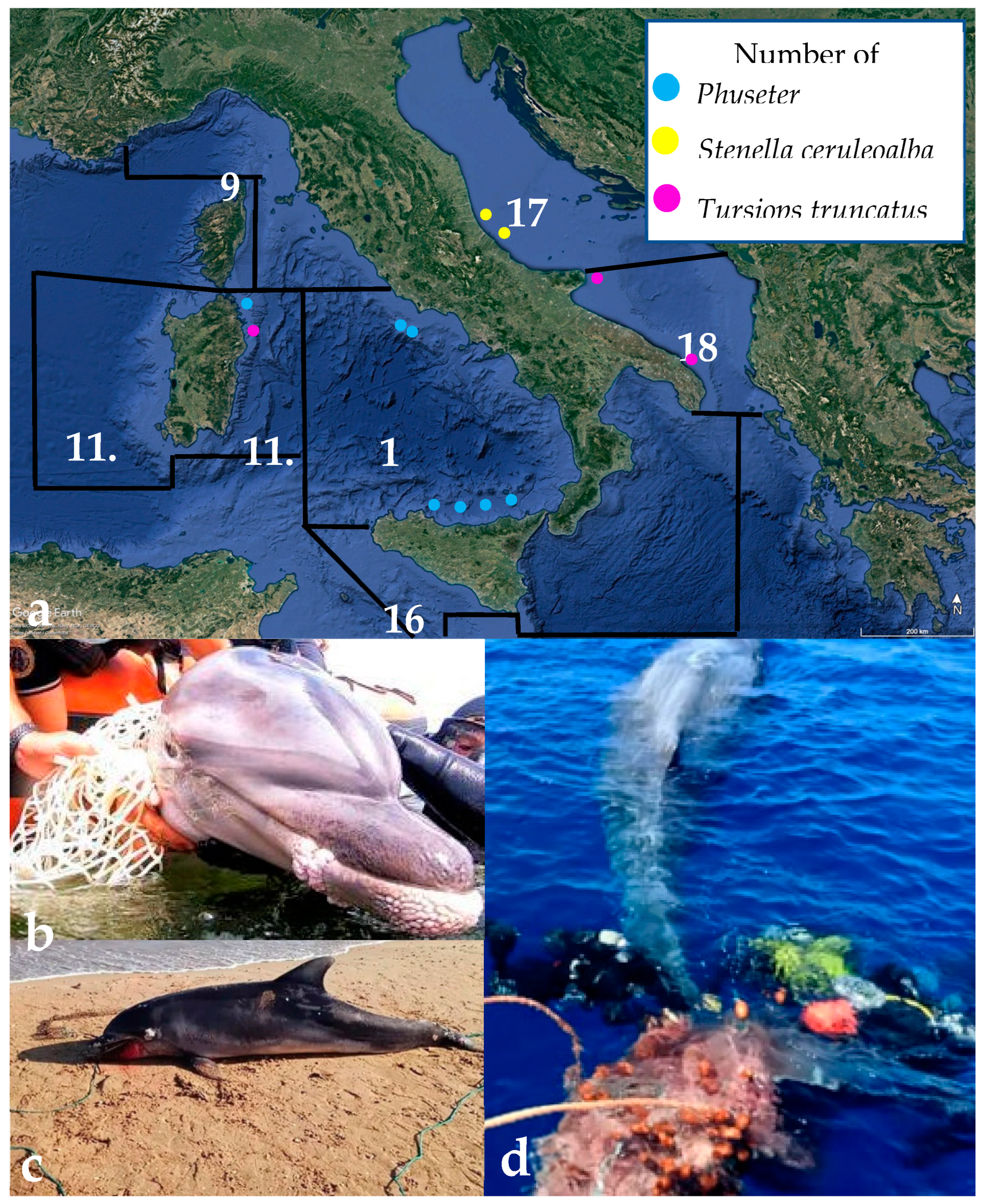

The cetaceans constituted the largest second group found in this study (Figure 5a). Most of the records regarded Physeter macrocephalus (4 ingestion and 3 entanglements), followed by Tursiops truncatus (1 ingestion and 2 entanglements) and Stenella coeruleoalba (1 ingestion and 1 entanglement) (Table S1, Figure 5b,c,d).

For what concerns seabirds, 3 different species (Larus michahellis, Phoenicopterus roseus, and Puffinus yelkouan) were recorded. L. michahellis (4 specimens) and Phoenicopterus roseus (1) were found entangled in fishing lines and P. yelkouan (1) was found with its legs trapped in a surgical mask (Table S1, Figure 6).

Regarding elasmobranchs, a specimen of Cetorhinus maximus was entangled with a fishing net, and two specimens of Dasyatis pastinaca were entangled with plastic bags and fishing lines. Two blue sharks, Prionace glauca, were entangled with a plastic ring, the first one, a juvenile specimen, was found dead with the ring around its snout, while the second was an adult specimen with a plastic ring around its body (Figure 6).

Two fish species, that is Oblada melanura and Serranus scriba, were found entrapped in a ghost net (pot). The crustacean, Homarus gammarus, and the mollusk Octopus vulgaris were entangled in a ghost net and in a plastic bottle, respectively (Table S1).

As regards the records found in the various GSAs, GSA 10 emerged as the area with the highest number of cases (34.6%), followed by GSA 11 (15%), GSA 9 (11.8%), GSA 16 (11%), GSA 17 and 19 (9.4%), and GSA 18 (8.7%) (Figure 7).

Sicily and Sardinia were the regions where the highest number of cases were recorded, with 40% and 15%, respectively. Moreover, when focusing on Sicily, it was observed that most cases were found on the smaller islands. Specifically, the Aeolian Islands with 27 cases, the Egadi Islands with 5 cases, and the Pelagie Islands with 2 cases.

When focusing exclusively on entanglement cases, the predominant litter type was fishing nets, accounting for 46% of the cases, followed by fishing lines at 23%, and plastic debris (15%, consisted essentially of plastic floats, plastic bottles, plastic sheets, and plastic rings) (Figure 8A). As regard the records of macroplastic ingestion, the dominant category of plastic litter consisted of 75% of plastic debris, which included items such as cups, bottles, filters, food packages, balloons, and balloon strings (Figure 8B).

Regarding the health status of the species, 74% of marine animals survived the impact with plastic waste, 24% died, while the health condition of 2% marine animals could not be confirmed. As regards the environment in which marine animals were found, 72% of cases were found in the sea, while the remaining 28% were on the beach. Among the total dead animals, 16% was found on the beach, and 9% in the sea.

As regards the surviving animals, 12% was found on the beach and 62% in the sea. Finally, there was 1% of animals for which their fate remained unknown. In Figure 9 the percentage of the type of litter in the studied cases is shown. Fishing nets appear to be the main source of entanglement for cetaceans and teleosts, fishing lines are the main source of entanglement in seabirds.

4. Discussion

The worldwide problem of marine litter, primarily consisting of plastic, poses a significant environmental concern, leading to adverse effects on marine biodiversity and ecosystems. This study was performed using social media and local Italian newspapers to establish a comprehensive database of observations and incidents related to marine animals interacting with plastic, especially ALDFGs. Despite the limitations of this study, as the publication of entanglement cases depends on the ethical standards and motivations of media users, it is possible that many cases are not reported in social media, a snapshot of interaction between plastic litter and marine species along the coasts of Italy can be drawn.

Regarding the chronological distribution of case, our study identified the earliest documented case dated back to 2009. The positive temporal trend of records, with a peak in findings in 2021, suggested that there was an increase of the number of interactions and/or in posting on social media.

In our study, some entangled species were of particular importance due to their status on the IUCN red list [42], two endangered species, namely C. maximus and C. mydas and five vulnerable species: C. caretta, D. coriacea, D. pastinaca, P. macrocephalus, and P. yelkouan. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of entangled with fishing net in C. maximus, O. melanura, S. scriba, H. gammarus, O. vulgaris, and P. roseus.

The marine turtles, C. caretta, C. mydas, D. coriacea, were the most impacted (78%) both for entanglement and plastic ingestion (56% and 44%, respectively). Among the three species reported, the loggerhead sea turtle was the most frequently recorded. The cetaceans constituted the largest second group found, exhibiting both plastic ingestion and entanglements. The entanglement of some groups of organisms like marine turtles and cetaceans was often reported in the scientific literature [41, 43-50]. However, entanglement events of crustaceans and mollusks were less investigated [51].

Among the categories of marine animals entangled, we found a limited number of cases involving teleost and elasmobranchs. The entanglement of these groups of organisms was reported in the scientific literature [52-55]. Specifically, entanglements of sharks in circular plastic debris was reported for several species (Galeocerdo cuvier, Isurus oxyrinchus, Prionace glauca, Carcharhinus galapagensis) [56,57]. The source of these circular materials appears to be primarily linked to fisheries, derived from plastic straps from bait boxes employed by longliners [58], or components of plastic barrels commonly used in industrial fishery [56], or detachable sections of bottle lids likely discarded by fishing or recreational boats [59]. Our findings indicated that 77% of the documented entanglements were associated with fishing, with the remaining 23% linked to other human activities.

In a study conducted in the Mediterranean Sea, Savels et al. [60] emphasized that, despite the limited and inconsistent availability of data on ALDFG, it was recognized as an issue of major concern. The synthetic polymers in fishing nets constitute the largest proportion of total litter pollution [61]. Moreover, research conducted in various regions of the Mediterranean Sea highlighted that fishing gear constituted the predominant source of documented marine litter, reaching levels as high as 89% [62,63].

Several studies worldwide observed a high percentage of entanglements in litter associated with fishing activity [5,8,41,55,56,64,65]. In line with our observations, Mghili et al. [41] highlighted that fishing-related litter constituted the majority (89%) of entanglements documented in the Moroccan Mediterranean.

Within the cases of ingestion, plastic debris originating from other human activities predominated, accounting for 78%, while fishing-related material constituted 22%. Cups, bottles, filters, food packages, balloons, and balloon strings have been found frequently involved. A surgical mask was responsible for the second case of entanglement of a specimen of P. yelkouan, related to the COVID-19 pandemic, as already reported by Karris et al. [66]. The ingestion of plastic debris is common from loggerhead turtle in the Mediterranean Sea [67-71]. Mrosovsky et al. [72] and Schuyler et al. [73] reported that plastic bags were often mistaken for gelatinous prey by several species of marine turtles. The study suggests that Italy is potentially a hotspot for interaction between marine litter and marine wildlife. In particular, the western GSAs seem to experience more significant impacts compared to the eastern ones. GSA 10 emerges as the most severely affected area, with a high number of reports, especially in the Aeolian Islands. Previous records of entanglement regard P. macrocephalus [74] and marine turtles [43].

5. Conclusions

Examining digital media can offer valuable insights for assessing impacts and devising strategies to mitigate the issue of ghost fishing. This study highlights the need for more research on the effects of ghost nets on wildlife, particularly on endangered animals. Our results underscore the critical importance of reducing the disposal of such waste. Additional research is necessary to understand the extent of this issue across Italy, with the help of citizen science. The current study represents a preliminary step toward establishing databases that document instances of ingestion and entanglement, which can be useful for conservation measures to be adopted in the Mediterranean GSAs.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Plastic interactions and marine species found in Italy an according to digital media.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.B.; funding acquisition T.B. and M.M.; data analysis T.B.; review and editing, T.B., B.M., M.M.; Investigation, M.M.; writing—original draft, T.B., M.M.; formal analysis, K.G., M.M.; project administration, T.B., M.M.; data and writing curation, B.M., K.G.; formal analysis, supervision, K.G, M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study has been funded by the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4 Component 2 Investment 1.4—Call for tender No. 3138 of 16 December 2021, rectified by Decree n.3175 of 18 December 2021 of the Italian Ministry of University and Research funded by the European Union—Next Generation EU. Award Number: Project code CN_00000033, Concession Decree No. 1034 of 17 June 2022 adopted by the Italian Ministry of University and Re-search, Project title “National Biodiversity Future Center—NBFC”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Original data are available as Supplementary Material.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Nicola Zizzo that help us in the species identification.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Barnes, D.K.A.; Galgani, F.; Thompson, R.C.; Barlaz, M. Accumulation and fragmentation of plastic debris in global environments. Phil. Trans. Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 1985-1998. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, R.C., Olsen, Y.; Mitchell, R.P.; Davis, A.; Rowland, S.J.; John, A.W.G.; McGonigle, D.; Russell, A.E. Lost at sea: where is all the plastic? Science, 2004, 304, 838. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gall, S.C.; Thompson, R.C. The impact of debris on marine life. Mar. Pollut. Bull., 2015 92, 170-179. [CrossRef]

- Kühn, S.; van Franeker, J.A. Quantitative overview of marine debris ingested by marine megafauna. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 151, 110858. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, E.M.; Botterell, Z.L.R.; Broderick, A.C.; Galloway, T.S.; Lindeque, P.K., Nuno, A.; Godley, B.J. A global review of marine turtle entanglement in anthropogenic debris: A baseline for further action. Endanger. Species Res. 2017, 34, 431 - 448. [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.J.B.; Bellini, C.; Bortolon, L.F.; Coluchi, R. Ghost nets haunt the olive ridley turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea) near the Brazilian islands of Fernando de Noronha and Atol das Rocas. Herpetol. Rev. 2012, 43, 245–246.

- Adelir-Alves, J.; Rocha, G.R.A.; Souza, T.F.; Pinheiro, P.C.; Freire, K.M.F. Abandoned, lost, or otherwise discarded fishing gears in rocky reefs of Southern Brazil. Braz. J. Oceanogr., 2016, 64 (4), 427–434. [CrossRef]

- Stelfox, M.; Hudgins, J.; Sweet, M. A review of ghost gear entanglement amongst marine mammals, reptiles and elasmobranchs. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 111, (1-2), 6–17.

- Azevedo-Santos, V.M.; Marques, L.M.; Teixeira, C.R.; Giarrizzo, T.; Barreto, R.; Rodrigues-Filho, J.L. Digital media reveal negative impacts of ghost nets on Brazilian marine biodiversity. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 172, 112821. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laist, D.W. Impacts of Marine Debris: Entanglement of Marine Life in Marine Debris Including a Comprehensive List of Species with Entanglement and Ingestion Records. In: Coe, J.M., Rogers, D.B. (Eds.), Marine Debris: Sources, Impacts, and Solutions. Springer, New York, 1997, 99–139. [CrossRef]

- Law, K.L. Plastics in the Marine Environment. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2017, 9 (1), 205–229. [CrossRef]

- Dolman, S.J.; Moore, M.J. Welfare Implications of Cetacean Bycatch and Entanglements. In: Butterworth, A. (Ed.), Marine Mammal Welfare: Human Induced Change in the Marine Environment and its Impacts on Marine Mammal Welfare. Springer International Publishing, 2017, 41–65. [CrossRef]

- Azevedo-Santos, V.M.; Hughes, R.M.; Pelicice, F.M. Ghost nets: A poorly known threat to Brazilian freshwater biodiversity. An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc., 2022, 94 (1). [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, D.S.; Goodwin, M.C. Gooseneck barnacles (Lepas spp.) ingest microplastic debris in the North Pacific subtropical gyre. Peer. J. 2013, 1, e184. [CrossRef]

- Schuyler, Q.; Wilcox, C.; Townsend, K.; Hardesty, B.; Marshall N. Mistaken identity? Visual similarities of marine debris to natural prey items of sea turtles. BMC Ecol. 2014, 14 ,14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suaria, G.; Avio, C.G.; Mineo, A.; Lattin, G.L.; Magaldi, M.G.; Belmonte, G.; Moore, C.J.; Regoli, F.; Aliani, S. The Mediterranean Plastic Soup: synthetic polymers in Mediterranean surface waters. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 37551. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cózar, A.; Sanz-Martín, M.; Martí, E.; González-Gordillo, J.I.; Ubeda, B.; Gálvez, J.Á.; et al. Plastic accumulation in the Mediterranean Sea. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, 4, 0121762. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coll, M.; Piroddi, C.; Steenbeek, J.; Kaschner, K.; Ben Rais Lasram F, Aguzzi J, et al. The Biodiversity of the Mediterranean Sea: Estimates, Patterns, and Threats. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, 8, e11842. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- wwf.it 2023. https://www.wwf.it/dove-interveniamo/.

- Angiolillo, M.; di Lorenzo, B.; Farcomeni, A.; Bo, M.; Bavestrello, G.; Santangelo, G.; Cau, A; Mastascusa, V.; Cau, A.; Sacco, F. Distribution and assessment of marine debris in the deep Tyrrhenian Sea (NW Mediterranean Sea, Italy). Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2015, 92, 149–159. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasquini, G.; Ronchi, F.; Strafella, P.; Scarcella, G., Fortibuoni, T. Seabed litter composition, distribution, and sources in the northern and central Adriatic Sea (Mediterranean). Waste Management, 2016, 58, 41-51. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cau, A.; Alvito, A.; Moccia, D.; Canese, S.; Pusceddu, A.; Rita, C.; Angiolillo, M.; Follesa, M.C. Submarine canyons along the upper Sardinian slope (Central Western Mediterranean) as repositories for derelict fishing gears. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 123, 357–364. [CrossRef]

- Pierdomenico, M.; Casalbore, D.; Chiocci, F.L. Massive benthic litter funnelled to deep sea by flashflood generated hyperpycnal flows. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Spedicato, M.T.; Zupa, W.; Carbonara, P.; Fiorentino, F.; Follesa, M.; Galgani, F.; Garcia, C.; Jadaud, A.; Ioakeimidis, C.; Lazarakis, G.; et al. Spatial Distribution of Marine Macro-Litter on the Seafloor in the Northern Mediterranean Sea: The MEDITS Initiative. Sci. Mar. 2019, 83. [CrossRef]

- Garofalo, G.; Quattrocchi, F.; Bono, G.; Di Lorenzo, M.; Di Maio, F.; Falsone, F.; Gancitano, V.; Geraci, M.L.; Lauria, V.; Massi, D.; et al. What Is in Our Seas? Assessing Anthropogenic Litter on the Seafloor of the Central Mediterranean Sea. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 266, 115213. [CrossRef]

- Pierdomenico, M.; Casalbore, D.; Chiocci, F.L. The key role of canyons in funnelling litter to the deep sea: a study of the Gioia canyon (southern Tyrrhenian Sea). Anthropocene 2020, 30, 100237. [CrossRef]

- Suaria, G.; Aliani, S. Floating debris in the Mediterranean Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014, 86, 494–504. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munari, C.; Corbau, C.; Simeoni U.; Mistri, M. Marine litter on Mediterranean shores: analysis of composition, spatial distribution, and sources in north-western Adriatic beaches. Waste Manag. 2016, 49, 483-490. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlachogianni, T.; Fortibuoni, T.; Ronchi, F.; Zeri, C.; Mazziotti, C., Tutman, P.; Varezić, D.B.; Palatinus, A.; et al. Marine litter on the beaches of the Adriatic and Ionian seas: an assessment of their abundance, composition, and sources. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 131, 745–756. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancuso, M.; Genovese, G; Porcino, N.; Natale, S.; Spagnuolo, D.; Morabito, M.; Bottari, T. Psammophytes as traps for beach litter in the Strait of Messina (Mediterranean Sea). Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2023, 65, 103057. [CrossRef]

- Porcino N., Bottari T., Falco F., Natale S., Mancuso, M. Posidonia spheroids entrapping plastic litter: Implication for beach clean-ups. Sustainability, 2023, 15 (22), 15740. [CrossRef]

- Fossi, M.C.; Coppola, D.; Baini, M.; Giannetti, M.; Guerranti, C.; Marsili, L., Clò, S. Large filter feeding marine organisms as indicators of microplastic in the pelagic environment: the case studies of the Mediterranean basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus) and fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus). Mar. Environ. Res. 2014, 100, 17–24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biagi, E.; Musella, M.; Palladino, G.; Angelini, V.; Pari, S.; Roncari, C.; Candela, M. Impact of Plastic Debris on the Gut Microbiota of Caretta caretta From North-western Adriatic Sea. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 127.

- Bottari, T.; Mancuso, M.; Pedà, C.; De Domenico, F.; Laface, F.; Schirinzi, G.F.; Battaglia, P.; Consoli, P.; Spanò, N.; Greco, S.; Romeo, T. Microplastics in the bogue, Boops boops: a snapshot of the past from the southern Tyrrhenian Sea. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 424, 127669. [CrossRef]

- Zitouni, N.; Cappello, T.; Missawi, O.; et al Metabolomic disorders unveil hepatotoxicity of environmental microplastics in wild fish Serranus scriba (Linnaeus 1758). Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 155872. [CrossRef]

- Santonicola, S.; Volgare, M.; Di Pace, E.; Mercogliano, R.; Cocca, M.; Raimo, G.; Colavita, G. Research and characterization of fibrous microplastics and natural microfibers in pelagic and benthic fish species of commercial interest. Ital. J. Food Safety 2023, 8, 12(1), 11032. [CrossRef]

- Quaglia, N.C.; Capuozzo, F.; Ceci, E.; Cometa, S.; Di Pinto, A.; Mottola, A.; Piredda, R.; Dambrosio, A. Preliminary survey on the occurrence of microplastics in bivalve mollusks marketed in Apulian fish markets. Italian Journal of Food Safety, 2023, 8, 12(2), 10906. [CrossRef]

- D’ambrosio, A.; Cometa, S.; Capuozzo, F.; Ceci, E.; Derosa, M.; Quaglia, N.G. Occurrence and Characterization of Microplastics in Commercial Mussels (Mytilus galloprovincialis) from Apulia Region (Italy). Foods 2023, 12, 1495. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cau, A.; Avio, C.G.; Dessì, C.; Follesa, M.C.; Moccia, D.; Regoli, F.; Pusceddu, A. Microplastics in the crustaceans Nephrops norvegicus and Aristeus antennatus: Flagship species for deep-sea environments? Environ. Pollut. 2019, 255. 113107. [CrossRef]

- Roman, L.; Schuyler, Q.; Wilcox, C.; Hardesty, B.D. Plastic pollution is killing marine megafauna, but how do we prioritize policies to reduce mortality? Conserv. Lett. 2021, 14, 2, e12781. [CrossRef]

- Mghili, B.; Keznine, M.; Analla, M.; Aksissou, M. The impacts of abandoned, discarded, and lost fishing gear on marine biodiversity in Morocco. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2023, 239, 106593. [CrossRef]

- IUCN, 2022. The IUCN red list of threatened species. Version 2022–2. https://www. iucnredlist.org. (accessed on 30 October 2023).

- Russo, G.; Di Bella, C.; Loria, G.R.; Insacco, G.; Palazzo, P.; Violani, C.; Zava, B. Notes on the influence of human activities on sea chelonians in Sicilian waters. J. Mt. Ecol. 2003, 7, 37-41.

- Jacobsen, J.K.; Massey, L.; Gulland, F. Fatal ingestion of floating net debris by two sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus) Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2010, 60(5), 765-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barreiros, J.P.; Raykov, V.S. Lethal lesions and amputation caused by plastic debris and fishing gear on the loggerhead turtle Caretta caretta (Linnaeus, 1758). Three case reports from Terceira Island, Azores (NE Atlantic), Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014, 86, 518-522. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benhardouze, W.; Aksissou, M.; Tiwari, M. Analysis of digestive tract contents from loggerhead sea turtles Caretta caretta (Linnaeus, 1758) stranded along the Northwest coast of Morocco. Cah. Biol. Mar. 2021, 62 (3), 205–215. [CrossRef]

- Orós, J.; Camacho, M; Calabuig, P.; Rial-Berriel, C.; Montesdeoca, N.; Déniz, S.; Luzardo, O.P. Postmortem investigations on leatherback sea turtles (Dermochelys coriacea) stranded in the Canary Islands (Spain) (1998–2017): Evidence of anthropogenic impacts. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 167. 112340. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, Y.; Vandeperre, F.; Santos, M.R.; Herrera, L.; Parra, H.; Deshpande, A.; Bjordal, K.A.; Pham, C.K.; Litter ingestion and entanglement in green turtles: An analysis of two decades of stranding events in the NE Atlantic. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 298. 118796. [CrossRef]

- Solomando, A.; Pujoil, F.; Sureda, A.; Pinya, S. Evaluating the Presence of Marine Litter in Cetaceans Stranded in the Balearic Islands (Western Mediterranean Sea). Biology 2022, 11(10), 1468. [CrossRef]

- Mghili, B.; Benhardouze, W.; Aksissou, M.; Tiwari, M. Sea turtle strandings along the Northwestern Moroccan coast: Spatio-temporal distribution and main threats. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2023, 237, 106539. [CrossRef]

- Lavers, J.L.; Sharp P.B.; Stuckenbrock, S.; Bond A.L. Entrapment in plastic debris endangers hermit crabs. J. Hazard. Mat. 2020, 387. 121703. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parton, K.J.; Galloway, T.S.; Godley, B.J. Global review of shark and ray entanglement in anthropogenic marine debris. Endang. Species Res. 2019, 39, 173–190. [CrossRef]

- Wegner, N.C.; Cartamil, D.P. Effects of prolonged entanglement in discarded fishing gear with substantive biofouling on the health and behavior of an adult shortfin mako shark, Isurus oxyrinchus. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2012, 64, 391–394. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mucientes, G.; Queiroz, N. Presence of plastic debris and retained fishing hooks in oceanic sharks. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 143, 6-11. [CrossRef]

- Perroca, J.F.; Giarrizzo, T.; Azzurro, E.; Luiz Rodrigues-Filho, J.L.; Silva, C.V.; Arcifa, M. S.; Azevedo-Santos, V.M. Negative Effects of Ghost Nets on Mediterranean Biodiversity. Aquatic Ecology, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Thiel, M.; Luna-Jorquera, G.; Alvarez-Varas, R.; Gallardo, C.; Hinojosa, I.A.; Luna, N.; Miranda-Urbina, D.; Morales, N.; Ory, N.; Pacheco, A.S.; Portflitt-Toro, M.; Zavalaga, C. Impacts of marine plastic pollution from continental coasts to subtropical gyres—fish, seabirds, and other vertebrates in the SE pacific. Front. Mar. Sci., 2018, 5, 238. [CrossRef]

- Afonso, S.; Fidelis, L. The fate of plastic-wearing sharks: Entanglement of an iconic top predator in marine debris. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 194, 115326. [CrossRef]

- Barreto, R., Bornatowski, H., Fiedler, F.N., Pontalti, M., da Costa, K.J., Nascimento, C., Kotas, J.E., 2019. Macro-debris ingestion and entanglement by blue sharks (Prionace glauca Linnaeus, 1758) in the temperate South Atlantic Ocean. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 145, 214–218. [CrossRef]

- Sazima, I., Gadig, O.B.F., Namora, R.C., Motta, F.S. Plastic debris collars on juvenile carcharhinid sharks (Rhizoprionodon lalandii) in Southwest Atlantic. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2002, 44, 1147–1149. [CrossRef]

- Savels, R.; Raes, L.; Papageorgiou, M.; Speelman, S. Economic assessment of abandoned, lost and otherwise discarded fishing gear (ALDFG) in the fishery sector of the Republic of Cyprus. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. 2022, 38.

- www.unep.org/unepmap/fr/node/4260?%2Fnode%2F4260, 2015. 4260.

- Bo, M.; Bava, S.; Canese, S.; Angiolillo, M.; Cattaneo-Vietti, R.; Bavestrello, G. Fishing impact on deep Mediterranean rocky habitats as revealed by ROV investigation. Biological Conservation, 2014, 171: 167–176.

- Tubau, X.; Canals, M; Lastras, G; Rayo, X.; Rivera, J.; Amblas, D. Marine litter on the floor of deep submarine canyons of the Northwestern Mediterranean Sea: The role of hydrodynamic processes. Progress in Oceanography, 2015, 134: 379–403.

- Woods, J.S.; Verones, F.; Jolliet, O.; V ́azquez-Rowe, I.; Boulay, A.M. A frameworkfor the assessment of marine litter impacts in life cycle impact assessment. Ecol. Ind. 2021, 129, 107918. [CrossRef]

- Høiberg, M.A.; Woods, J.S.; Verones, F. Global distribution of potential impact hotspots for marine plastic debris entanglement. Ecol. Ind. 2022, 135, 108509. [CrossRef]

- Karris, G.; Savva, I.; Kakalis, E.; Bairaktaridou, K.; Espinosa, C.; Smith, M. S.; Botsidou, P.; Moschous, S.; Voulgaris, M.D.: Peppa, E.; Panayides, P.; Hadjistyllis, H.; Iosifides, M. First sighting of a pelagic seabird entangled in a disposable COVID-19 facemask in the Mediterranean Sea. Medit. Mar. Sci. 2023, 24 (1): 50 - 55. [CrossRef]

- Gramentz, D. Involvement of loggerhead turtle with plastic, metal, and hydrocarbon pollution in the central Mediterranean. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 1988, 19, 11–13. [CrossRef]

- Tomás, J.; Guitart, R.; Mateo, R.; Raga, J.A. Marine debris ingestion in loggerhead sea turtles, Caretta caretta, from the Western Mediterranean. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2002, 44, 211–216. [CrossRef]

- Casale, P.; Abbate, G.; Freggi, D.; Conte, N.; Oliviero, M.; Argano, R. Foraging ecology of loggerhead sea turtle Caretta caretta in the central Mediterranean Sea: evidence for a relaxed life history model. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 2008, 372, 265– 276. [CrossRef]

- azar, B.; Gracan, R. Ingestion of marine debris by loggerhead sea turtles, Caretta caretta, in the Adriatic Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2011, 62, 43–47. [CrossRef]

- Campani, T.; Baini, M.; Giannetti, M.; Cancelli, F.; Mancusi, C.; Serena, F.; Marsili, L.; Casini, S.; Fossi, M.C. Presence of plastic debris in loggerhead turtle stranded along the Tuscany coasts of the Pelagos Sanctuary for Mediterranean Marine Mammals (Italy). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2013, 74, 225–230. [CrossRef]

- Mrosovsky,N.; Ryan, G.D. ; James, M.C. Leatherback turtles: the menace of plastic. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2009, 58, 287-289. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuyler, Q.; Hardesty, B.D.; Wilcox, C.; Townsend, K. Global analysis of anthropogenic debris ingestion by sea turtles. Conserv. Biol. 2014, 28: 129–139. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pace, D.S; Miragliuolo, A.; Mussi, B. Behaviour of a social unit of sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus) entangled in a driftnet off Capo Palinuro (Southern Tyrrhenian Sea, Italy). J. Cetacean Res. Manag. 2008, 10(2), 131-135. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Mediterranean Geographical Sub-Areas (GSAs) – FAO- Res. GFCM/33/2009/2 on the establishment of geographical subareas in the GFCM area of application. www.fao.org/gfcm/data/gsas/en/ .

Figure 1.

Mediterranean Geographical Sub-Areas (GSAs) – FAO- Res. GFCM/33/2009/2 on the establishment of geographical subareas in the GFCM area of application. www.fao.org/gfcm/data/gsas/en/ .

Figure 2.

Temporal trend of the number of entanglement and ingestion records reported by digital media between 2009 -2023 in Italy.

Figure 2.

Temporal trend of the number of entanglement and ingestion records reported by digital media between 2009 -2023 in Italy.

Figure 3.

Percentage of records in marine animals.

Figure 4.

Map of records in marine turtles (a). Caretta caretta and Dermochelys coriacea entangled in fishing nets (b,c); C. caretta entangled in plastic packaging (d); C. caretta entangled in fishing net and ropes (e); C. caretta entangled in a plastic sheet (f); C. caretta with fishing line and hook within the digestive tract (g). https://www.ilgolfo24.it/salvata-una-tartaruga-intrappolata-in-una-rete/; https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=836762696444440&id=814078758712834&sfnsn=scwspmo; https://www.ansa.it/canale_ambiente/notizie/animali/2017/06/12/salvata-tartaruga-charlie-quasi-uccisa-dalla-plastica_46d5dd4d-dc28-4aec-b335-7cfe123b68e1.html; https://www.ilgolfo24.it/salvata-una-tartaruga-intrappolata-in-una-rete/; https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=836762696444440&id=814078758712834&sfnsn=scwspmo; https://www.ansa.it/canale_ambiente/notizie/animali/2017/06/12/salvata-tartaruga-charlie-quasi-uccisa-dalla-plastica_46d5dd4d-dc28-4aec-b335-7cfe123b68e1.html; https://www.instagram.com/p/CJ1sxhmF9gc/?igshid=MTc4MmM1YmI2Ng%3D%3D;https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=300158085684564&set=pb.100070711249928.-2207520000&type=3;https://www.instagram.com/p/CESMRPODrnr/?igshid=MTc4MmM1YmI2Ng%3D%3D.

Figure 4.

Map of records in marine turtles (a). Caretta caretta and Dermochelys coriacea entangled in fishing nets (b,c); C. caretta entangled in plastic packaging (d); C. caretta entangled in fishing net and ropes (e); C. caretta entangled in a plastic sheet (f); C. caretta with fishing line and hook within the digestive tract (g). https://www.ilgolfo24.it/salvata-una-tartaruga-intrappolata-in-una-rete/; https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=836762696444440&id=814078758712834&sfnsn=scwspmo; https://www.ansa.it/canale_ambiente/notizie/animali/2017/06/12/salvata-tartaruga-charlie-quasi-uccisa-dalla-plastica_46d5dd4d-dc28-4aec-b335-7cfe123b68e1.html; https://www.ilgolfo24.it/salvata-una-tartaruga-intrappolata-in-una-rete/; https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=836762696444440&id=814078758712834&sfnsn=scwspmo; https://www.ansa.it/canale_ambiente/notizie/animali/2017/06/12/salvata-tartaruga-charlie-quasi-uccisa-dalla-plastica_46d5dd4d-dc28-4aec-b335-7cfe123b68e1.html; https://www.instagram.com/p/CJ1sxhmF9gc/?igshid=MTc4MmM1YmI2Ng%3D%3D;https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=300158085684564&set=pb.100070711249928.-2207520000&type=3;https://www.instagram.com/p/CESMRPODrnr/?igshid=MTc4MmM1YmI2Ng%3D%3D.

Figure 5.

Map of records in cetaceans in the Italian GSAs (a). Examples of plastic entanglement of cetaceans in fishing nets: Tursiops truncatus (b); Stenella coeruleoalba (c); Physeter macrocephalus (d). https://www.terremarsicane.it/spiaggiato-sulla-costa-abruzzese-un-delfino-senza-vita-ucciso-da-reti-da-pesca-perse-o-abbandonate/; https://www.primopianomolise.it/citta/termoli/126668/plastica-in-mare-delfino-spiaggiato-a-rio-vivo/;

https://scienze.fanpage.it/le-reti-fantasma-che-hanno-intrappolato-il-capodoglio-furia-uccidono-ogni-anno-300mila-cetacei/.

Figure 5.

Map of records in cetaceans in the Italian GSAs (a). Examples of plastic entanglement of cetaceans in fishing nets: Tursiops truncatus (b); Stenella coeruleoalba (c); Physeter macrocephalus (d). https://www.terremarsicane.it/spiaggiato-sulla-costa-abruzzese-un-delfino-senza-vita-ucciso-da-reti-da-pesca-perse-o-abbandonate/; https://www.primopianomolise.it/citta/termoli/126668/plastica-in-mare-delfino-spiaggiato-a-rio-vivo/;

https://scienze.fanpage.it/le-reti-fantasma-che-hanno-intrappolato-il-capodoglio-furia-uccidono-ogni-anno-300mila-cetacei/.

Figure 6.

Map of records in seabirds and fish (a). Larus michahellis entrapped in fishing lines (b); Puffinus yelkouan entrapped in a surgical mask (c); Prionace glauca entangled by a plastic ring (d); Dasyatis pastinaca entangled by fishing lines and plastic bag (e). https://www.ivg.it/2019/09/finale-ligure-gabbiano-reale-impigliato-in-una-lenza-soccorso-dai-volontari-enpa/?amp;https://www.ohga.it/una-mascherina-chirurgica-rischia-di-strozzarla-due-pescatori-siciliani-salvano-una-berta-minore; https://napoli.repubblica.it/cronaca/2020/09/20/foto/ascea_il_ministro_costa_libera_un_pesce_trigone_intrappolato_in_una_busta_di_plastica-267964345/1/#:~:text=Home-,Ascea%2C%20il%20ministro%20Costa%20libera%20un%20pesce%20trigone%20intrappolato%20in,nel%20Parco%20nazionale%20del%20Cilento; https://www.ilmessaggero.it/AMP/societa/squalo_ucciso_plastica_mare-4001532.html.

Figure 6.

Map of records in seabirds and fish (a). Larus michahellis entrapped in fishing lines (b); Puffinus yelkouan entrapped in a surgical mask (c); Prionace glauca entangled by a plastic ring (d); Dasyatis pastinaca entangled by fishing lines and plastic bag (e). https://www.ivg.it/2019/09/finale-ligure-gabbiano-reale-impigliato-in-una-lenza-soccorso-dai-volontari-enpa/?amp;https://www.ohga.it/una-mascherina-chirurgica-rischia-di-strozzarla-due-pescatori-siciliani-salvano-una-berta-minore; https://napoli.repubblica.it/cronaca/2020/09/20/foto/ascea_il_ministro_costa_libera_un_pesce_trigone_intrappolato_in_una_busta_di_plastica-267964345/1/#:~:text=Home-,Ascea%2C%20il%20ministro%20Costa%20libera%20un%20pesce%20trigone%20intrappolato%20in,nel%20Parco%20nazionale%20del%20Cilento; https://www.ilmessaggero.it/AMP/societa/squalo_ucciso_plastica_mare-4001532.html.

Figure 7.

Percentage of records found in different Italian GSAs.

Figure 8.

Percentage of observed entanglements (A) and ingestion (B) cases by litter type in Italy.

Figure 9.

Percentage of the type of litter in cetaceans, seabirds, marine turtles, teleost, elasmobranchs, and invertebrates between 2009 and 2023.

Figure 9.

Percentage of the type of litter in cetaceans, seabirds, marine turtles, teleost, elasmobranchs, and invertebrates between 2009 and 2023.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Copyright: This open access article is published under a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license, which permit the free download, distribution, and reuse, provided that the author and preprint are cited in any reuse.

Impact of Plastic Pollution on Marine Biodiversity in Italy

Teresa Bottari

et al.

,

2023

Ghost Gears in the Gulf of Gabès: Alarming Situation and Sustainable Solution Perspectives

Hana Ghaouar

et al.

,

2024

Plastic Litter from Shotgun Ammunition in Marine Ecosystems – Problems and Solutions

Niels Kanstrup

et al.

,

2021

MDPI Initiatives

Important Links

© 2024 MDPI (Basel, Switzerland) unless otherwise stated