Preprint

Article

Human Perception of Birds in Two Brazilian Cities

Altmetrics

Downloads

119

Views

36

Comments

0

A peer-reviewed article of this preprint also exists.

This version is not peer-reviewed

Submitted:

21 December 2023

Posted:

22 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Alerts

Abstract

Understanding how humans perceive animals is important for biodiversity conservation, however, only a few studies about this issue were carried out in South America. We selected two Brazilian cities to assess people’s perceptions of birds: Bauru (São Paulo, Brazil) and Belo Horizonte (Minas Gerais, Brazil). From the bird data we gathered, we developed a questionnaire and applied it between September 2020 and June 2021. The data obtained were analyzed by simple counts, Likert scale, and percentages. Also, open questions were placed on the Free Word Cloud Generator website. Our study confirmed that most respondents are aware of the importance of birds to ecological balance and that respondents had a generally positive attitude towards most of the bird species. However, they disliked exotic species such as the Domestic Dove and the House Sparrow, which are associated with disease, dirt, and disgust. Respondents also underestimated the number of birds that can live in urban areas and the song of birds is still a sense less explored and perceived by people. The concept of environmental perception seeks to cover aspects and understanding these human–biodiversity relationships is essential to successfully guide public policies, urban planning interventions, and environmental education activities.

Keywords:

Subject: Biology and Life Sciences - Ecology, Evolution, Behavior and Systematics

1. Introduction

Wildlife has coexisted with urban environments for thousands of years [1]. Cities are unique ecosystems [2,3], where biodiversity is fundamental for the delivery of important ecosystem services such as water protection, reduction of heat island effect, floods, noises, and air pollution [4,5]. Also, nature has positive effects on human well-being and health [6,7,8,9]. Since most humans live in urban regions, cities are the prime places where people can experience nature on a daily basis [10]. However, while there is a general consensus that nature in urban areas should be increased, the way people perceive the animals that live within cities varies greatly. Human perceptions of wildlife encompass a wide spectrum of emotions, ranging from admiration and respect to fear or even hatred [11].

Animals are not all equally liked: in general, birds, mammals, and amphibians/reptiles are liked most, while the attitude towards arthropods and other invertebrates is less positive among people [10]. However, there are some exceptions: mammals such as coyotes may be perceived with either indifference or fear [12] and rats are the least appreciated mammals among people [13]. On the other hand, insects such as butterflies are also popular, different from others such as cockroaches [14]. Furthermore, increasing familiarity with animals not only increases the range of attitudes towards them, but those attitudes may become more intense, either positive or negative [10].

Perception is linked to sensations, while attitude is a cultural posture formed by a long succession of perceptions [15]. There are five senses that allow humans to perceive and experience the world: sight, smell, taste, hearing, and touch; the way we interpret and apprehend the information transmitted by our senses and sensations in the world we live in is called perception [16]. Perception can be defined as ’the way an individual observes, understands, interprets, and evaluates a referent object, action, experience, individual, policy, or outcome’ [17]. Our perception is based on our experience: there is no interior perception without exterior perception: “all external perception is immediately synonymous with a certain perception of my body, just as all perception of my body is made explicit in the language of external perception” [16]. However, perceptions are also a myriad of other factors related to collective attributes (e.g., gender, race), values, norms, beliefs, preferences, and knowledge [18]. Therefore, understanding local people’s perceptions and attitudes toward urban wildlife is imperative for successful human-wildlife co-existence.

Considering research on this issue, there are very few studies analyzing people’s perceptions of urban wildlife, and the list of animals investigated is still very limited [10,13,14]. A systematic review identified several knowledge gaps: more than 80% of the studies about urban wildlife involved mammals (only three studies) and the lowest frequency of these studies was in South America [11]. Among birds, only one study was conducted about people’s perception of them [11]. Birds are of vital importance for ecological balance: they are responsible for seed dispersal and pollination, the control of insect populations, and assist in the balance of the food chain as predators and prey [19,20,21,22]. Even though birds are essential to ecological balance, how do people perceive them?

In this study, we aim to identify how people perceive birds in two Brazilian cities: Bauru (São Paulo State, Brazil) and Belo Horizonte (Minas Gerais, Brazil). Understanding how humans perceive animals plays a significant role in comprehending the contemporary human-nature relationship. Filling this knowledge is essential for planning environments where humans and animals interact and to garner broad support for biodiversity conservation in urban areas [2,10,11]. Several studies report that more intimate contact with nature can increase peoples’ tolerance towards biodiversity and the willingness to protect it [14,23].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study areas and bird data

We assessed people's perception about birds in two Brazilian cities, Bauru (São Paulo State, Brazil) and Belo Horizonte (Minas Gerais, Brazil). We gathered bird data for Bauru across streets and parks of the city (see below). For Belo Horizonte, we used information from a published study about birds in the streets [24]. Thus, it would be possible to assess how people perceive bird species they may encounter on a daily basis based on data on the bird communities that occupy each city. Furthermore, both cities present specificities that may influence how people perceive urban bird communities.

Bauru is a medium-sized city in the central-west region of the state of São Paulo (22°18'55'' S, 49°3'41'' W) with about 379.146 inhabitants and 567.85 hab/km2 [25]. The city is located in the transition zone between the Atlantic Forest and Brazilian Savanna (Cerrado) - two biodiversity hotspots – presenting 296 bird species; its urban landscape presents high heterogeneity, with streams, rivers, forest fragments and important urban parks [26]. Belo Horizonte (W 19° 55' 37", S 43° 56' 34") is the capital of the state of Minas Gerais and is one of the first planned cities in Brazil. It is the fourth richest city, contributing 1.46% to the national GDP, trailing only behind São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and Brasília, respectively. The city is also located in the transition zone between the Atlantic Forest and the Brazilian Savanna, and presents 370 bird species [26,27]. According to the last census, the population is 2,315,560 inhabitants and its population density is 6.988,18 hab/km2.

In Bauru, we did bird observations using 10 minute point counts during the mornings with favorable weather [28,29], between December 2018 and March 2019 (summer season in Brazil) and from September to December 2019 (spring season). This period coincides with the breeding period of most species in southeastern Brazil, including migratory species [20]. Sites were visited six times, three during the summer and three during the spring, totaling 108 field observations.

For Belo Horizonte, we used bird data previously published in the literature [24,30]. These studies carried out a bird survey in 60 sample locations, distributed in streets through the southern region of Belo Horizonte. Site selection aimed to represent the variation of the influences of the streets and arboreal and herbaceous vegetation within the study; the point samples were at least 200 meters away from each other [24]. They conducted the fieldwork during the first three hours of daylight on days with favorable weather (sunny and non-windy days), only on working days – to avoid great variation in people and vehicles in circulation. The bird survey was between September 2014 and January 2015, period that also coincides with birds’ breeding season [24].

2.2. Assessing human perception on urban birds

From the bird data we gathered (Supplementary Material Table S1), we developed a questionnaire for each city (Text.S2) to analyze how the human population perceives the local avifauna. We carried out an opinion survey between September 2020 and June in 2021, with the use of an online questionnaire created by Google Forms tool [10]. Questionnaires were prepared with open and choice structured questions: open responses are those in which the respondent answers in their own words, while choice structured questions are structured in the form of a choice of some answer alternatives [31]. Questionnaires are considered an appropriate method because they limit the range of answers a participant can give and allow for a standardization of results [10]. We sent them by e-mail and through Facebook and WhatsApp groups of Bauru and Belo Horizonte residents.

The answers to the questionnaires were anonymous, but the first part of the questionnaire asked for sociodemographic information regarding gender, age, education, and family income. These data are important to understand the social context that was achieved. In the second part, we addressed the following open and choice structured questions:

Open questions:

- Describe in one word how you feel about urban birds

- What do you believe is a benefit of birds in cities?

- Do you believe that there is a harm caused by birds in cities?

Choice structured questions:

- 4.

- How many different birds do you think you have seen within the urban area of Bauru?

- 5.

- 371 bird species have already been recorded within the entire territory of Belo Horizonte (which includes forested, rural and urban areas)/ 276 bird species have already been recorded within the entire territory of Bauru (which includes forested, rural and urban areas). How many do you believe are capable of living in the urban area?

We also used a Likert scale [10,32,33,34], one of the most popular methods for conducting opinion surveys, in which, from a self-descriptive statement, the respondent chooses as a response option a scale of points with verbal descriptions that include extremes – such as “strongly agree” and “strongly disagree” [35]. Statements were created regarding the contribution of birds in ecological processes such as seed dispersal, pollination, and pest control. Thus, the respondents should express their degree of agreement with each sentence. We used 5 points of scale from “strongly agree” and “strongly disagree”. We addressed the following statements:

- Birds contribute to seed dispersal

- Birds contribute to plant pollination

- Birds contribute to the control of pests, insects and other animals.

- Birds contribute to the prevention of the incidence of diseases

Finally, we presented images of 20 birds (the 15 most frequent and the 5 most rare at each city) and songs of the six most frequent species at each city. For these questions, respondents would need to mark which species they had seen and/or which sounds they had heard across the city.

2.3. Analyzing peoples’ perceptions towards birds

First we analyzed the sociodemographic information and created a table with the main characteristics of the respondents participating in our research (Table 1). Data obtained from closed and Likert scale questions were analyzed by simple counts and percentages [36]. We also analyzed if the species most commonly observed and heard by people were also the most frequently recorded species. In this context, 'frequency' (f) refers to the number of times each species was recorded during the survey. In Bauru, we established 36 sampling points (24 on streets and 12 in parks) and conducted six visits to each, resulting in a total of 216 bird records. In Belo Horizonte, the bird survey was conducted during the breeding season from September 2014 to January 2015, with observations taken at 60 sampling sites across streets, each with 3 replications, totaling 180 bird observations."

In the case of open questions, we carried out two different approaches: to analyze the answers for question “describe in one word how you feel about urban birds”, the words were placed in the Free Word Cloud Generator website (https://www.freewordcloudgenerator.com/), which is a tool that creates a “cloud” of words, highlighting those that appear most frequently. This website also points how many times each word was mentioned in each city. To analyze open questions 2 and 3, we grouped answers according to harm or benefit mentioned and carried out simple counts and percentages to find out the main kinds of harm or benefit that were pointed by respondents.

3. Results

In Bauru, 112 responses were obtained, with 63.4% self-reported that they were female and 36.6% reported that they were male. Regarding to education, 97.3% of respondents had undergraduate degrees, in which 41.0% also had postgraduate degrees. Regarding income, 32.1% of respondents have low income, 25.9% have medium income, 22.3% have upper-middle income and 14.3% have high income. In Belo Horizonte, 123 responses were obtained, with 53.7% self-reported that they were female, 44.7% reported that they were male, and 1.6% declared their selves as non-binary gender. Regarding to education, 93.6% of respondents had undergraduate degree, of which 51.0% also had a postgraduate degree. Regarding income, 14.6% of respondents have low income, 16.3% have medium income, 25.2% have upper-middle income and 38.2% have high income (Table 1).

Unfortunately, the responses collected did not represent the population of these cities because these questionnaires only reached the group of people who were willing to respond online. Because the present research was carried out during the pandemic, it was difficult to access different sociodemographic groups. Since we largely depended on social media, our approach ended up selecting a specific group according to the affinities and algorithms of each user.

Regarding the responses, in Bauru, 91.1% of respondents strongly agree that birds have a fundamental role in seed dispersal, 77.7% that birds contribute to plant pollination, and 83% that birds contribute to the control of pests, insects, and other animals (Figure 1). In Belo Horizonte, 94.3% of respondents strongly agree that birds have a fundamental role on seed dispersal, 86.2% that birds contribute to plant pollination, and 86.2% that birds contribute to the control of pests, insects, and other animals (Figure 1).

In the case of open questions, when people were asked if they believed there were damages caused by birds in cities, most said yes (Bauru: 66% and Belo Horizonte: 70%). When asked which damages, most people mentioned disgust and worry for the diseases that domestic pigeons (Columba livia) can transmit. Other problems/discomfort mentioned by people were electrical wiring damages, noise, dirt, and worry concerning the ecological imbalance, in a situation of uncontrolled population of pigeons and the presence of other exotic birds (Figure 2).

When people were asked which benefits they attribute to birds in cities, most respondents mentioned seed dispersal (Bauru: 36; Belo Horizonte: 29), biological control, and life, joy, and well-being (Bauru: 24; Belo Horizonte: 35), joy and well-being (Bauru: 24; Belo Horizonte: 26. The category “other” represents all different benefits that were mentioned only a few times such as: hope (1), environmental indicators (2), environmental education (2), spiritual connection (3), and biodiversity (5). (Figure 3).

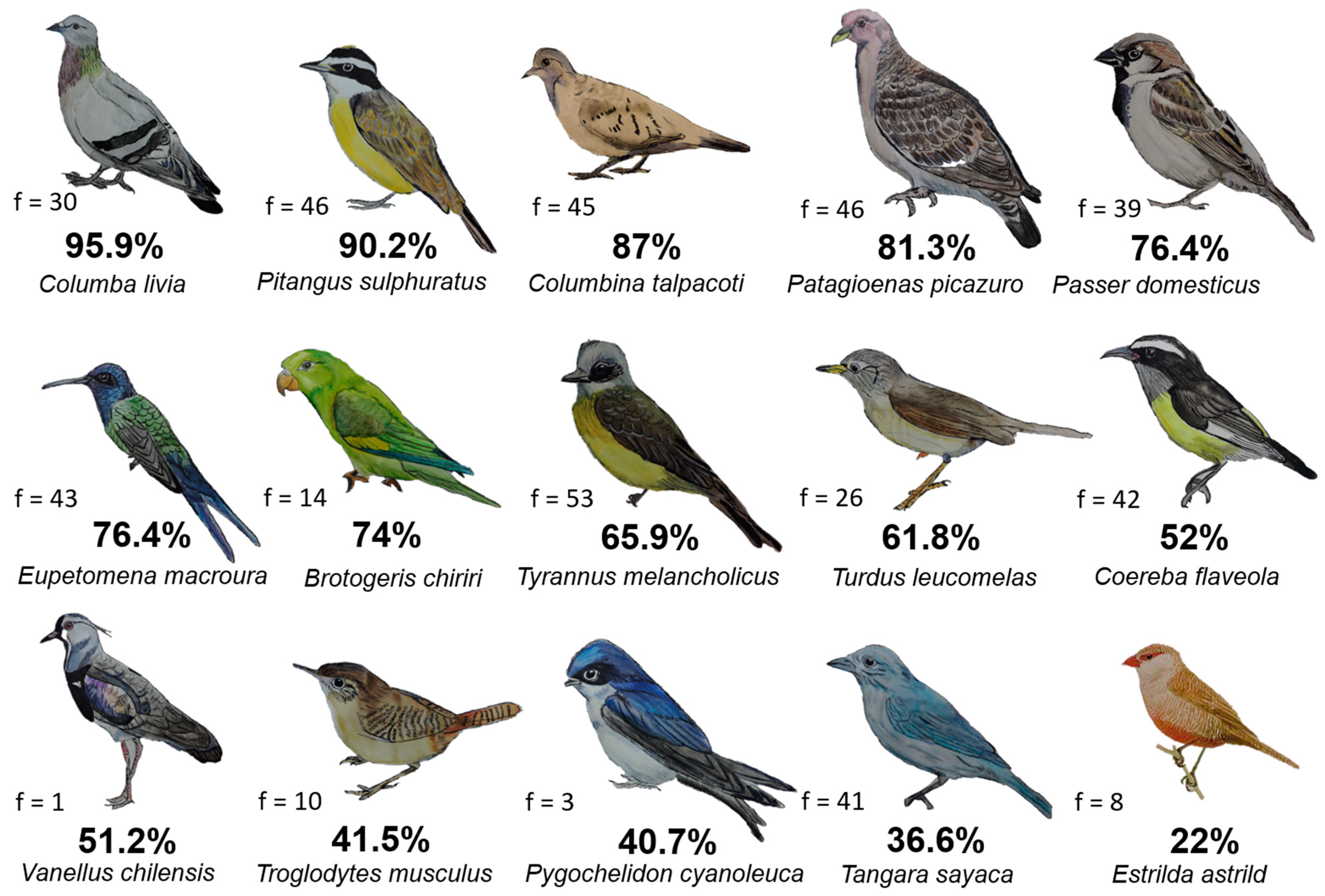

In Bauru, the birds most seen were the Eared Dove (Zenaida auriculate), Domestic pigeon (Columba livia), Great Kiskadee (Pitangus sulphuratus), House Sparrow (Passer domesticus), and White-eyed Parakeet (Psittacara leucophthalmus). Four of those species are also the ones most frequently observed across the city (Pitangus sulphuratus, 149 records; Zenaida auriculata, 141; Psittacara leucophthalmus, 139; Passer domesticus, 136; Figure 4). In Belo Horizonte, the birds most seen by people were the Domestic pigeon (Columba livia), Great Kiskadee (Pitangus sulphuratus), Ruddy Ground-Dove (Columbina talpacoti), Picazuro Pigeon (Patagioenas picazuro) and House Sparrow (Passer domesticus). These species are exactly the most frequent in Belo Horizonte according with the published literature [24]: Columbina talpacoti, 594 records; Columba livia, 490; Patagioenas picazuro, 386; Passer domesticus, 350; Pitangus sulphuratus, 345; Figure 5).

The results also confirmed that, in both cities, the rarest species of each city according to our bird data are also the ones that people saw the least (Figure 6 and Figure 7).

Considering bird songs, most respondents had already heard at least some of the most frequent ones among those presented in the questionnaire (Bauru: 88.4%; Belo Horizonte: 91.9%). Only few people have declared that they did not hear any song (Bauru: 11.6% and Belo Horizonte: 8.1%). In both cities, Great Kiskadee (Pitangus sulphuratus) was the most heard and one of the most seen bird species. Picazuro Pigeon (Patagioenas picazuro) and House Sparrow (Passer domesticus) appear at second and third place of the most heard bird species, depending on the city (Figure 8 and Figure 9).

Regarding birds that live in urban areas, most respondents (68.7% in Bauru and 49.6% in Belo Horizonte) believed that only less than 35% of species are able to live in urban areas. However, this percentage is higher: in Bauru we observed in our bird survey 36% of the species that occur in the municipality, which includes natural and agricultural areas (according to Wikiaves records). Belo Horizonte 41.24% of birds observed in the municipality occur across the streets [24]. This result showed that people have a low perception of the number of bird species that may live near them. In fact, only 16.1% of respondents in Bauru and 19.5% in Belo Horizonte got the correct percentages.

Finally, the word cloud analysis showed the main feelings that respondents associated with urban birds. In Bauru, the most frequent words were admiration (7), happiness (7), beauty (5), life (5), wonderful (4), depends (3), peace (3), freedom (3), tranquility (3), worry (3; Figure 10). In Belo Horizonte they were admiration (13), happiness (10), beauty (8), love (4), important (4) and peace (3; Figure 11). The interesting thing to note is that the first three most cited words were the same in both cities (Figure 10 and Figure 11). Another point that we noticed is the feelings towards birds are mostly, and only a few people also mentioned feelings like disgust, worry, and illness.

4. Discussion

Our study confirmed that most respondents are aware of the importance of birds to ecological balance. When people were asked which benefits they attribute to birds in cities, most respondents mentioned seed dispersal and biological control in both cities. Birds play vital roles as seed dispersers in human-altered landscapes, helping to maintain and restore plant communities [19,21,22]. Flower pollination and ecological balance were also two benefits frequently mentioned by people, confirming that most people with higher education backgrounds perceive and understand the importance of birds.

We also found that respondents had a generally positive attitude towards most of the bird species. Considering social aspects, most birds within cities provide to humans connection with nature, life, joy, beauty, and well-being. Many people in Bauru and Belo Horizonte mentioned these as the main benefits provided by birds. Other studies also found that most people have positive attitudes towards birds [37]. Research in the field of environmental psychology has shown that people’s exposure to natural systems positively affects human well-being and health [9,38,39]. However, there is a clear difference in human attitude and perception according to species. While the majority of people associated most bird species with positive words – such as admiration, happiness, and beauty – they also disliked exotic species such as the Domestic Pigeon and the House Sparrow. These species are associated to disease, dirt, disgust, and ecological imbalance, according to respondents. This result is similar with other research, in which they observed that some particular species are more appreciated (e.g. squirrels) than others (e.g. mosquitoes and cockroaches) [10].

Overall, our study provides evidence that people with higher education background perceive and are able to recognize the bird species most frequent in cities. Most of the species presented in our questionnaire are common in urban environments in southeast Brazil and respondents were familiar with a high number of them. In Bauru, four out of five birds most seen by respondents were also the ones most frequently observed through our bird survey. In Belo Horizonte, the birds most seen by respondents were exactly the most frequent [24]. This is an interesting result because the research was conducted across streets, thus people probably have more contact with these species on a daily basis, which may explain the greater coincidence with the results [24].

However, we observed that respondents underestimated the number of birds that can live in urban areas. Also, the song of birds is still a sense less explored and perceived by people. Probably, this could happen because of the noise pollution (mainly traffic noise) and the highly dynamic urban life that makes it difficult for some people to hear or notice bird songs within cities. Despite most respondents were able to recognize them, when comparing to vision, people less explore the hearing sense. This shows the need to expand environmental education initiatives. Environmental education in early childhood provides many opportunities to sensitize children to interact with nature, promoting new generations to be environmentally aware of the importance of nature [6]. Moreover, it is necessary to conciliate birds and people relationship, through the implementation of multifunctional ecological corridors [40] and other initiatives such as birdwatching events [41].

Understanding how humans perceive animals is very important for creating a conservation agenda and planning environments for successful human-wildlife co-existence [10,11,42]. In this way, it is essential to involve a mix of researchers, practitioners, policy makers, urban planners together with citizen supports to create strategies for a better management of urban wildlife [2,43]. Birds are part of the urban landscape and stimulate the human senses. They bring good sensations and feelings, increasing the connection of humans with nature in urban environments. A highly 'imaginable' city would invite our eyes and ears to have an active participation, so that the sensory domain would be expanded and deepened [44].

Nevertheless, it is important to mention that the scope of this study was limited to people who have at least an undergraduate degree. The present research was carried out during the pandemic, which reduced the access different sociodemographic groups. Because we largely depended on social media, we ended up selecting a specific group according to the affinities and algorithms of each user. Ideally, the number of questionnaires should have a sample size that represents the population and should be applied in person to reach people of different social classes, ages, and genders, following the same proportionality of the population data of each municipality, as performed in many works [45,46]. Furthermore, the choice of interviewees must be random, but based on the age and sex proportion of the original population, according to the logic of Systematic Design [47]. Despite that, our study provides interesting evidence about human perception of birds, an interesting field of study that deserves to be deepened. It would be interesting to carry out more studies like this focusing on other audiences and social groups and in other cities, regions and countries to assess if people that live under a variety of urban conditions have similar perceptions about birds. Cities are ecological and socioeconomic spaces for living and non-living things [3] and understanding how human and ecological processes coexist can help cities become more sustainable places [48].

5. Conclusions

We showed that people with undergraduate backgrounds can recognize the most frequent bird species and are aware of the ecological importance of birds for the balance of urban ecosystems. We also showed that most people associate most bird species with positive sensations and feelings such as beauty, joy, well-being, and peace. On the other hand, species such as the Domestic Dove are considered pests and generate negative sensations. The concept of environmental perception seeks to cover aspects that influence the natural, physical, and humanized environment through attitudes, values, and worldviews [15]. Thus, understanding these human–biodiversity relationships is to be aligned successfully with that of public health by policymakers and practitioners [42]. The city exists through bodily experience, which is multisensory [49] thus studying birds and perceiving them as part of the urban landscape, can be useful to stimulate the imaginability of cities and, at the same time, contribute to the conservation of a group of animals that is particularly important for the ecological balance of urban ecosystems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: title.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Gabriela Graviola, Milton Cezar Ribeiro and João Carlos Pena; Data curation, Gabriela Graviola; Formal analysis, Gabriela Graviola and Milton Cezar Ribeiro; Funding acquisition, Gabriela Graviola, Milton Cezar Ribeiro and João Carlos Pena; Investigation, Gabriela Graviola, Milton Cezar Ribeiro and João Carlos Pena; Methodology, Gabriela Graviola, Milton Cezar Ribeiro and João Carlos Pena; Project administration, Gabriela Graviola; Resources, Gabriela Graviola, Milton Cezar Ribeiro and João Carlos Pena; Software, Gabriela Graviola; Supervision, João Carlos Pena; Validation, Gabriela Graviola; Visualization, Gabriela Graviola, Milton Cezar Ribeiro and João Carlos Pena; Writing – original draft, Gabriela Graviola; Writing – review & editing, Gabriela Graviola, Milton Cezar Ribeiro and João Carlos Pena. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (CAPES), the São Paulo Research Foundation (grants #2013/50421-2; 2020/01779-5; 2021/08322-3; 2021/08534-0; 2021/10195-0; 2021/10639-5; 2022/10760-1; 2018/00107-3), and the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (grants #442147/2020-1; 440145/2022-8; 402765/2021-4; 313016/2021-6; 440145/2022-8).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Soulsbury, C.D., White, P.C.L. Human–wildlife interactions in urban areas: a review of conflicts, benefits and opportunities. Wildl. Res. 2015. 42, 541. [CrossRef]

- Collins, M.K., Magle, S.B., Gallo, T. Global trends in urban wildlife ecology and conservation. Biol. Conserv. 261, 2021. 109236. [CrossRef]

- Maddox, D.; Nagendra, H.; Elmqvist, T.; Russ A. Chapter 1: Advancing Urbanization. In: Cornell University. Urban Environmental Education. 2017. Cornell University.

- Schwarz, N.; Moretti, M.; Bugalho, M.N.; Davies, Z.G.; Haase, D.; Hack, J.; Hof, A.; Melero, Y.; Pettf, T.J. & Knappk, S. Understanding biodiversity-ecosystem service relationships in urban areas: A comprehensive literature review. Ecosystem Services, 2017. 27: 161–171. [CrossRef]

- Vailshery, L.S.; Jaganmohan, M. & Nagendra, H. Effect of street trees on microclimate and air pollution in a tropical city. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening, 2013. 12(3), 408–415. [CrossRef]

- Derr, V.; Chawla, L.; Pevec, I. Chapter 16: Early Childhood. In: Cornell University. Urban Environmental Education. 2017, Cornell University.

- Sandifer, P. A., Sutton-Grier, A. E., Ward, B. P. Exploring connections among nature, biodiversity, ecosystem services, and human health and well-being: Opportunities to enhance health and biodiversity conservation. Ecosystem Services, 2015, 12, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T., Mitchell, R., De Vries, S., Frumkin, H. Nature and Health. Annual Review of Public Health, 2014. 35(1), 207–228. [CrossRef]

- Louv, R. Last Child in the Woods: saving our children from nature-deficit disorder. Hardcover, United States, April, 2005.

- Sweet, F.S.T.; Noack, P.; Hauck, T.E.; Weisser, W.W. The relationship between knowing and liking for 91 urban animal species among students. Animals, 2023, 13(3), 488. [CrossRef]

- Basak, S.M.; Rostovskaya, E.; Birks, J. & Wierzbowska, I.A. Perceptions and attitudes to understand human-wildlife conflict in an urban landscape – A systematic review. Ecological Indicators, 2023 151. [CrossRef]

- Elliot, E.E., Vallance, S., Molles, L.E. Coexisting with coyotes (Canis latrans) in an urban environment. Urban Ecosyst, 2016, 19, 1335–1350. [CrossRef]

- Bjerke, T., & Østdahl, T. Animal-related attitudes and activities in an urban population. Anthrozoos, 17(2), 2004, 109– 129. [CrossRef]

- Hosaka, T., Sugimoto, K., & Numata, S. Childhood experience of nature influences the willingness to coexist with biodiversity in cities. Palgrave Communications, 2017, 3(1). [CrossRef]

- Tuan, Y. Space and Place: the perspective of experience. University of Minnesota Press, 2001.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. Phenomenology of Perception. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 1996.

- Bennett, N.J., Using perceptions as evidence to improve conservation and environmental management. Conserv Biol 2016, 30, 582–592. [CrossRef]

- Dickman, A.J. Complexities of conflict: the importance of considering social factors for effectively resolving human–wildlife conflict. Anim. Conserv. 2010, 13, 458–466. [CrossRef]

- Pejchar, L.; Pringlea, R.M.; Ranganathana, J.; Zookb, J.R.; Duranc, G.; Oviedoc, F.; Daily, G.C. Birds as agents of seed dispersal in a human-dominated landscape in southern Costa Rica. Biological Conservation, 2008, 141: p. 536-544. [CrossRef]

- Sick, H. Ornitologia Brasileira. Nova Fronteira., Rio de Janeiro, RJ, 1997.

- Wenny, D.G.; Sekercioglu, Ç.H.; Cordeiro, N.J.; Rogers, H.S. & Kelly, D. Chapter five: Seed Dispersal by Fruit-Eating Birds. In: Sekercioglu, Ç.H.; Wenny, D.G. & Whelan, C.J. Why Birds Matter - Avian Ecological Function and Ecosystem Services. University of Chicago Press, 2016.

- Whelan, C.J.; Sekercioglu, Ç.H.; Wenny, D.G. Why birds matter: from economic ornithology to ecosystem services. Journal of Ornithology, July 2015. 20 July. [CrossRef]

- Unterweger, P., Schrode, N., & Betz, O. Urban Nature: Perception and Acceptance of Alternative Green Space Management and the Change of Awareness after Provision of Environmental Information. A Chance for Biodiversity Protection. Urban Science, 2017, 1(3), 24. [CrossRef]

- Pena, J. C., Martello, F., Ribeiro, M. C., Armitage, R. A., Young, R. J., & Rodrigues, M. Street trees reduce the negative effects of urbanization on birds. PLoS ONE, 2017, 12(3), 1–19. [CrossRef]

- IBGE. Estimativas da população residente nos municípios brasileiro. 2022. ftp://ftp.ibge.go.

- SEMMA. Plano Municipal de Conservação e Recuperação da Mata Atlântica e do Cerrado., 2015. SEMMA - Secretaria Municipal do Meio Ambiente, Prefeitura de Bauru.

- Pena, J.C.C.; Magalhães, D.M.; Moura, A.C.M.; Young, R.J. & Rodrigues, M. The Green Infrastructure of a Highly Urbanized Neotropical City: the Role of the Urban Vegetation in Preserving Native Biodiversity. Revista Da Sociedade Brasileira de Arborização Urbana, 2016, 11(4), 66. [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, H.; Cahill, A.; Jones, M.; Marsden, S. Estimating Bird Densities Using Distance Sampling. In: Lloyd, M.; Jones; S. Marsden. (Eds). Bird surveys - Expedition Field Techniques, 2000, pp. 34-55.

- Gregory, R. D., Gibbons, D. W., & Donald, P. F. Bird Census And Survey Techniques. In W. J. Sutherland, I. Newton, & R. Green (Eds.), Bird Ecology and Conservation: A Handbook of Techniques, 2004, pp. 17–56. Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Pena, J.C.; Ovaskainen, O.; Macgregor-Fors, I.; Teixeira, C.P.; Ribeiro, M.C. The relationships between urbanization and bird functional traits across The streetscape. Landscape and Urban Planning, 2023, vol. 232. [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.M.R.G. Para entender a pesquisa qualitativa. Bauru: Unesp-FAAC, 2017.

- Farinha, B.S. Árvores para quem? Um estudo sobre percepção ambiental e distribuição socioeconômica da floresta urbana na cidade de São Paulo. Dissertação de Mestrado em Conservação em Ecossistemas Florestais, Escola Superior de Agricultura "Luiz de Queiroz" (ESALQ), Universidade de São Paulo (USP), Piracicaba, SP, 70p. 2022. https://www.teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/11/11150/tde-06042022-141809/publico/Barbara_Saeta_Farinha_versao_revisada.pdf.

- Mota, M.D.S.; Régis, M.D.M. & Nascimento, A.P.B. (2019). Perfil e e percepção ambiental dos frequentadores do Parque Tenente Siqueira Campos (Trianon), no Município de São Paulo/SP. Periódico Eletrônico Fórum Ambiental da Alta Paulista, 2019. v.15. n. 2, p. 95-110.

- Régis, M.D.M.; Lamano-Ferreira, A.P.N.; Ramos, H.R. Relato Técnico: percepção de frequentadores sobre espaço, estrutura e gestão do Parque da Água Branca, SP. Periódico Técnico e Científico Cidades Verdes, v. 3, n. 6, p. 43-54, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Frankenthal, R. Entenda a escala Likert e como aplicá-la em sua pesquisa, 2017. https://mindminers.com/blog/entenda-o-que-e-escala-likert/.

- Borysiak, J.; Stepniewska, M. Perception of the Vegetation Cover PatternPromoting Biodiversity in Urban Parks by Future Greenery Managers. Land, 2022, 11, 341. [CrossRef]

- Harris, E., De Crom, E., Wilson, A., Pigeons and people: mortal enemies or lifelong companions? A case study on staff perceptions of the pigeons on the University of South Africa, Muckleneuk campus. J. Public Aff. 2016, 16, 331–340. [CrossRef]

- Lovasi, G.S.; Quinn, J.W.; Neckerman, K.M.; Perzanowski, M.S. & Rundle, A. Children living in areas with more street trees have lower prevalence of asthma, Short Report, United States, 2008.

- Adams, J.D; Greenwood, D.A.; Thomashow, M.; Russ, A. (2017) Chapter 7: Sense of place. In: Cornell University. Urban Environmental Education. Cornell University, 2017.

- Graviola, G.R.; Ribeiro, M.C.; Pena, J.C. Reconciling humans and birds when designing ecological corridors and parks within urban landscapes. Ambio, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Bhakti, T.; Lodi, M.L.; Marujo, L.S.; Pena, J.C. & Rodrigues, M. Beyond birds’ conservation: Engaging communities for the conservation of urban green spaces. El Hornero 38 (1), 2023 ·. [CrossRef]

- Pett, T. J., Shwartz, A., Irvine, K. N., Dallimer, M.,; Davies, Z. G. Unpacking the people-biodiversity paradox: A conceptual framework. Bio Scienc, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Konig, H.J., Kiffner, C., Kramer-Schadt, S., Fürst, C., Keuling, O., Ford, A.T., Human–wildlife coexistence in a changing world. Conserv. Biol. 2020, 34, 786–794. [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K. A imagem da cidade. Lisboa: Edições 70, 1960.

- Rosa, G. Por uma ressignificação do Rio Tietê no Oeste Paulista: Barra Bonita e Pederneiras. Dissertação de Mestrado em Arquitetura e Urbanismo da Faculdade de Arquitetura, Artes e Comunicação (FAAC), UNESP (Universidade Estadual Paulista "Júlio de Mesquita Filho"), Bauru, SP, 212p. 2020.

- Foloni, F.M. Rios sobre o asfalto: conhecendo a paisagem para entender as enchentes, 210p. Dissertação de Mestrado em Arquitetura e Urbanismo, Universidade Estadual Paulista. Faculdade de Arquitetura, Artes e Comunicação, Bauru, 2018.

- Hurlbert, S. Pseudoreplication and the Design of Ecological Field Experiments. Ecological Monographs, Vol. 54, No. 2., pp. 187-211, 1984. [CrossRef]

- Marzluff, J.M.; Shulenberger, E.; Endlicher, W.; Simon, U.; Brunnen C. Z.; Alberti, M.; Bradley, G.; Ryan, C. An introduction to Urban Ecology as an interaction between humans and nature. In:___. (Org.) Urban Ecology: an International Perspective on the Interaction Between Humans and Nature. Springer, New York, 2008.

- Pallasmaa, J. Os Olhos da Pele: a Arquitetura e os Sentidos. Bookman, 1ed., 2011Author 1, A.; Author 2, B. Book Title, 3rd ed.; Publisher: Publisher Location, Country, 2008; pp. 154–196.

Figure 1.

Percentage of strongly agreement with the questionaries’ statements.

Figure 2.

Damages that may be caused by birds according to respondents from Belo Horizonte (Minas Gerais, Brazil) and Bauru (São Paulo, Brazil).

Figure 2.

Damages that may be caused by birds according to respondents from Belo Horizonte (Minas Gerais, Brazil) and Bauru (São Paulo, Brazil).

Figure 3.

Benefits associated with birds in cities mentioned by respondents from Belo Horizonte (Minas Gerais, Brazil) and Bauru (São Paulo, Brasil). The number means how many times each benefit was mentioned and not how much people said it, once many people mentioned more than one benefit.

Figure 3.

Benefits associated with birds in cities mentioned by respondents from Belo Horizonte (Minas Gerais, Brazil) and Bauru (São Paulo, Brasil). The number means how many times each benefit was mentioned and not how much people said it, once many people mentioned more than one benefit.

Figure 4.

Percentage of people who observed these 15 most frequent bird species in Bauru (São Paulo, Brazil) according to the bird survey we conducted across the city. The bird’s pictures are watercolors painted by Gabriela Rosa, created based on scientific illustrations from Handbook of the Birds of the World (HBW Alive), in which I am subscribed.

Figure 4.

Percentage of people who observed these 15 most frequent bird species in Bauru (São Paulo, Brazil) according to the bird survey we conducted across the city. The bird’s pictures are watercolors painted by Gabriela Rosa, created based on scientific illustrations from Handbook of the Birds of the World (HBW Alive), in which I am subscribed.

Figure 5.

Percentage of people who observed these 15 most frequent bird species in Belo Horizonte (Minas Gerais, Brazil) according to published literature (Pena et al. 2017). The bird’s pictures are watercolors painted by Gabriela Rosa, created based on scientific illustrations from Handbook of the Birds of the World (HBW Alive), in which I am subscribed.

Figure 5.

Percentage of people who observed these 15 most frequent bird species in Belo Horizonte (Minas Gerais, Brazil) according to published literature (Pena et al. 2017). The bird’s pictures are watercolors painted by Gabriela Rosa, created based on scientific illustrations from Handbook of the Birds of the World (HBW Alive), in which I am subscribed.

Figure 6.

Percentage of people who have seen these 5 least frequent bird species (f = 1 for all of them) in Bauru (São Paulo). The bird’s pictures are watercolors painted by Gabriela Rosa, created based on scientific illustrations from Handbook of the Birds of the World (HBW Alive), in which I am subscribed.

Figure 6.

Percentage of people who have seen these 5 least frequent bird species (f = 1 for all of them) in Bauru (São Paulo). The bird’s pictures are watercolors painted by Gabriela Rosa, created based on scientific illustrations from Handbook of the Birds of the World (HBW Alive), in which I am subscribed.

Figure 7.

Percentage of people who have seen these 5 least frequent bird species in Belo Horizonte (Minas Gerais), Brazil. The bird’s pictures are watercolors painted by Gabriela Rosa, created based on scientific illustrations from Handbook of the Birds of the World (HBW Alive), in which I am subscribed.

Figure 7.

Percentage of people who have seen these 5 least frequent bird species in Belo Horizonte (Minas Gerais), Brazil. The bird’s pictures are watercolors painted by Gabriela Rosa, created based on scientific illustrations from Handbook of the Birds of the World (HBW Alive), in which I am subscribed.

Figure 8.

Percentage of people who have heard the song of these bird species in Bauru (São Paulo, Brazil). The bird’s pictures are watercolors painted by Gabriela Rosa, created based on scientific illustrations from Handbook of the Birds of the World (HBW Alive), in which I am subscribed.

Figure 8.

Percentage of people who have heard the song of these bird species in Bauru (São Paulo, Brazil). The bird’s pictures are watercolors painted by Gabriela Rosa, created based on scientific illustrations from Handbook of the Birds of the World (HBW Alive), in which I am subscribed.

Figure 9.

Percentage of people who have heard the song of these bird species in Belo Horizonte (Minas Gerais, Brazil). The bird’s pictures are watercolors painted by Gabriela Rosa, created based on scientific illustrations from Handbook of the Birds of the World (HBW Alive), in which I am subscribed.

Figure 9.

Percentage of people who have heard the song of these bird species in Belo Horizonte (Minas Gerais, Brazil). The bird’s pictures are watercolors painted by Gabriela Rosa, created based on scientific illustrations from Handbook of the Birds of the World (HBW Alive), in which I am subscribed.

Figure 10.

cloud analysis of the main feelings that respondents associate about urban birds in Bauru (São Paulo, Brazil).

Figure 10.

cloud analysis of the main feelings that respondents associate about urban birds in Bauru (São Paulo, Brazil).

Figure 11.

cloud analysis of the main feelings that respondents associate about urban birds in Belo Horizonte (Minas Gerais, Brazil).

Figure 11.

cloud analysis of the main feelings that respondents associate about urban birds in Belo Horizonte (Minas Gerais, Brazil).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the respondents participating in research.

| Variable | Cities | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Bauru | Belo Horizonte | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 41 (36.6%) | 55 (44.7%) | |

| Female | 71 (63.4%) | 66 (53.7%) | |

| Other | 0 (0%) | 2 (1.6%) | |

| Age | |||

| Until 25 years | 33 (29.5%) | 16 (13.0%) | |

| 26 to 35 years | 36 (32.1%) | 44 (35.8%) | |

| 36 to 45 years | 12 (10.7%) | 32 (26%) | |

| 46 to 60 years | 22 (19.6%) | 17 (13.8%) | |

| 61 to 74 years | 8 (7.1%) | 14 (11.4%) | |

| More than 75 years | 1 (0.9%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Education | |||

| Elementary and middle school | 2 (1.8%) | 0 (0%) | |

| High school | 9 (8.0%) | 4 (3.3%) | |

| Bachelor study incomplete | 29 (25.9) | 12 (9.8%) | |

| Bachelor study complete | 24 (21.4%) | 36 (29.3%) | |

| Master ans doctarate degree | 47 (42.0%) | 71 (57.6%) | |

| Post-doctoral degree | 1 (0.9%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Family Income | |||

| Untill 1000 reais | 2 (1.8%) | 1 (0.8%) | |

| 1001 to 3000 reais | 36 (32.1%) | 18 (14.6%) | |

| 3001 to 5000 reais | 29 (25.9%) | 20 (16.3%) | |

| 5001 to 10000 reais | 25 (22.3%) | 31 (25.2%) | |

| More than 10000 reais | 16 (14.3%) | 47 (38.2%) | |

| No anwser | 4 (3.6%) | 6 (4.9%) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Copyright: This open access article is published under a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license, which permit the free download, distribution, and reuse, provided that the author and preprint are cited in any reuse.

Human Perception of Birds in Two Brazilian Cities

Gabriela Rosa Graviola

et al.

,

2023

An Exploratory Attitude and Belief Analysis of Ecotourists’ Destination Image Assessments and Behavioral Intentions

Rich Harrill

et al.

,

2023

In the Lap of Gods: Sacred Bonds and Socio-Economic Dynamics in Resolving Human- Bonnet Macaque Conflicts for Harmonious Coexistence

Chaithra Bhagavathi Parambu

et al.

,

2024

MDPI Initiatives

Important Links

© 2024 MDPI (Basel, Switzerland) unless otherwise stated