Preprint

Article

Maternal Diabetes Mellitus and Neonatal Outcomes in Bisha: A Retrospective Cohort Study.

Altmetrics

Downloads

151

Views

77

Comments

0

A peer-reviewed article of this preprint also exists.

This version is not peer-reviewed

Submitted:

23 February 2024

Posted:

23 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Alerts

Abstract

Background: Maternal diabetes mellitus (MDM) is associated with increased risks for adverse neonatal outcomes. However, the impact of MDM on neonatal outcomes in Bisha, a city in Saudi Arabia, is not well-documented. This study aims to investigate the impact of MDM on neonatal outcomes in the Maternity and Children’s Hospital (MCH), Bisha, Saudi Arabia. Methods: A retrospective cohort study was conducted on 181 pregnant women with diabetes and their neonates diagnosed at Maternity and Children’s Hospital (MCH), Bisha, Saudi Arabia, between October 5, 2020, and November 5, 2022. The primary outcome was a composite of adverse neonatal outcomes, including stillbirth, neonatal death, macrosomia, preterm birth, respiratory distress syndrome, hypoglycemia, and congenital anomalies. Logistic regression analyses were used to adjust for potential confounders. Results: The total sample size was 181. The average age of patients was 34 years (SD=6.45). The majority of the patients were diagnosed with GDM, 147 (81.2%), and pre-GDM, 34 (18.8%). Neonates born to mothers with MDM had a higher risk of adverse neonatal outcomes compared to those born to mothers without MDM (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 1.46, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.25-1.70). The risks of macrosomia (aOR = 1.74, 95% CI: 1.38-2.19), LBW (aOR = 1.32, 95% CI: 1.06-1.66), and RDS (aOR = 1.57, 95% CI: 1.28-1.93) were significantly higher among neonates born to mothers with MDM. Types of DM were statistically significant with some neonatal outcomes: hypoglycemia (p-value = 0.017), macrosomia (p-value = 0.050), and neonatal death (p-value = 0.017). Conclusion: MDM is associated with an increased risk of adverse neonatal outcomes in Bisha. Early identification and management of MDM may improve neonatal outcomes and reduce the burden of neonatal morbidity and mortality in this population.

Keywords:

Subject: Medicine and Pharmacology - Endocrinology and Metabolism

1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a metabolic disorder characterized by chronic hyperglycemia or elevated blood glucose levels beyond the normal range [1]. During pregnancy, diabetes is classified as pregestational (pre-GDM) or gestational diabetes (GDM). Pre-GDM occurs when women are diagnosed with type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus before pregnancy. Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) is caused by an autoimmune reaction leading to the destruction of β cells in the pancreas, resulting in insulin deficiency, whereas type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is caused by inadequate insulin production from β cells in the pancreas and insulin resistance in peripheral tissues [2,3]. GDM is a carbohydrate metabolism impairment or carbohydrate intolerance that is often diagnosed in the second or third trimester of pregnancy and is strongly associated with type 2 diabetes after pregnancy [2,3,4].

The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) reports that the global prevalence of diabetes among adults (20-79 years) was 10.5% in 2021 and is expected to reach 11.3% by 2030 [1]. In Saudi Arabia, diabetes mellitus affects 30% of the population [5], while the prevalence of diabetes in pregnancy was found to be approximately 16.7% in 2021 [1]. Of the maternal diabetes cases, 85% were GDM, and 15% were pre-GDM [6]. In Saudi Arabia, the prevalence of GDM is higher than in other countries, affecting 19.6% of pregnant women [7]. In Riyadh, the prevalence of diabetes among all pregnancies ranges from 4.3% to 24.3%, including pre-GDM and GDM. Out of 9723 women, 24.2% had GDM and 4.3% had pre-GDM [8]. GDM prevalence varies widely due to obesity, diabetes epidemics, and advanced maternal age during pregnancy, and these conditions continue to worsen globally [4].

Pregnant women with well-controlled diabetes through a healthy diet, exercise, and appropriate body weight generally have healthy neonates. However, uncontrolled maternal diabetes is strongly associated with cesarean deliveries and operative vaginal deliveries [6,9]. Uncontrolled maternal diabetes can adversely affect neonatal health, leading to metabolic and hematologic disorders, respiratory distress, cardiac disorders, and neurologic impairment due to perinatal asphyxia and birth trauma [10]. Both pre-GDM and GDM are strongly linked to unfavorable pregnancy outcomes [11]. Diabetes during pregnancy is associated with significant short- and long-term effects, such as an increased risk of obesity and diabetes development in both mothers and children, as well as extremely high healthcare costs [4,12].

To date, no research has been conducted on the impact of maternal diabetes on neonatal outcomes in Bisha. Therefore, investigating the effects of maternal diabetes on neonatal health in Bisha, Saudi Arabia, is essential. This study aims to determine the impact of maternal diabetes on neonatal outcomes at the Maternal and Child Health (MCH) Center in Bisha.

2. Materials and Methods

The study utilized a retrospective cohort design to examine 181 pregnant women with diabetes and their neonates who were diagnosed at Maternity and Children’s Hospital (MCH) in Bisha, Saudi Arabia. The study took place in the Bisha province, southwest of Saudi Arabia, which has a population of approximately 398,256. Maternity and Children Hospital (MCH), Bisha, was the primary location for the study with a bed capacity of 100 and 41 groups.

The study population included all pregnant women with diabetes and their neonates who had complete medical records between October 5, 2020, and November 5, 2022. The study included all pregnant women with diabetes and their neonates who had complete medical records. The study excluded women under 18, those planning to give birth at a different hospital, those without diabetes, those not currently pregnant, and those with incomplete medical records.

After obtaining permission from MCH, Bisha, the study collected antenatal, perinatal, and postnatal data from patient medical records, including demographic data and clinical information on pregnancy and delivery characteristics. Data on neonatal morbidity and mortality, including birth weight, respiratory distress syndrome (RDS), low birth weight (LBW), neonatal hypoglycemia, neonatal death, admission to neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), cardiac disorders, neurologic impairment due to perinatal asphyxia, and birth traumas were also collected. The neonate's status was followed up after birth.

Data were entered into Microsoft Office Excel 2019 and analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) 23 version. The analysis involved providing a complete description of the dataset using numbers, frequencies, and percentages of the variables in the study. Bivariate analysis or cross-tab procedures were used to test the dependent variables against each predictor variable. Any p-value of ≤0.05 was considered significant.

The study defined T1DM, T2DM, GDM, neonatal macrosomia, and LBW. The study received ethical clearance from the University of Bisha College of Medicine (UBCOM) ethical committee with the registration number (H-06-BH-087), and permission from MCH, Bisha, was obtained. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

3. Results

The Maternity and Children’s Hospital (MCH) in Bisha, Saudi Arabia, was the site of a study involving 181 pregnant women with diabetes and their neonates. The study revealed a connection between maternal diabetes mellitus and unfavorable neonatal outcomes in Bisha. The results underscore the significance of timely diagnosis and effective management of diabetes during pregnancy as a means of enhancing neonatal outcomes in the region.

3.1. Maternal age

The average of patients age is around 34 years (SD=6.45) as shown in Figure 1.

3.2. Maternal characteristics

Table 1 represents the maternal characteristics of the participants: The majority of the patients were Saudi, 168 (92.8%), and from urban areas, 148 (81.8%). Most of the patients had a family history of diabetes, 40 (22.1%). The majority of the patients were diagnosed with diabetes mellitus during pregnancy (GDM), 147 (81.2%). Most of the patients had 3 babies or more, 115 (63.5%). Most of the patients were delivered by C-section, 172 (95%). The patients had a history of neonatal death, 12 (6.6%). Birth weight was found as less than 2.5kg (low birth weight) in 21 (11.6%) neonates and more than 4 kg (macrosomia) in 32 (17.7%) neonates. Types of diabetes were statistically significant with some maternal characteristics: time-diagnosed DM (p-value = 0.010) and types of delivery (p-value = 0.049) as shown in Table 1.

3.3. Neonatal outcome

Table 2 represents the neonatal outcomes. The majority of the neonate presented normal accented, 87 (48.1%); congenital heart disease, 39 (21.5%); macrosomia, 28 (15.5%); LBW, 21 (11.6%); RDS, 16 (8.8%); sepsis, 12 (6.6%); DM, 3 (1.7%); development and growth disorder, 2 (1.1%); hypoglycemia, 1 (0.6%); prematurity, 1 (0.6%); and neonatal death, 1 (0.6%). Most neonates after birth were cured, 106 (59.6%) or improved from their condition, 66 (36.5%), while some neonates developed complications, 8 (4.4%), and died, 1 (0.6%). NICU admission among neonates was 65 (35.9%). Types of diabetes were statistically significant with some neonatal outcomes: hypoglycemia (p-value = 0.017) as well as macrosomia (p-value = 0.050) and neonatal death (p-value = 0.017) as shown in Table 2.

3.4. Diagnosis of DM in pregnancy

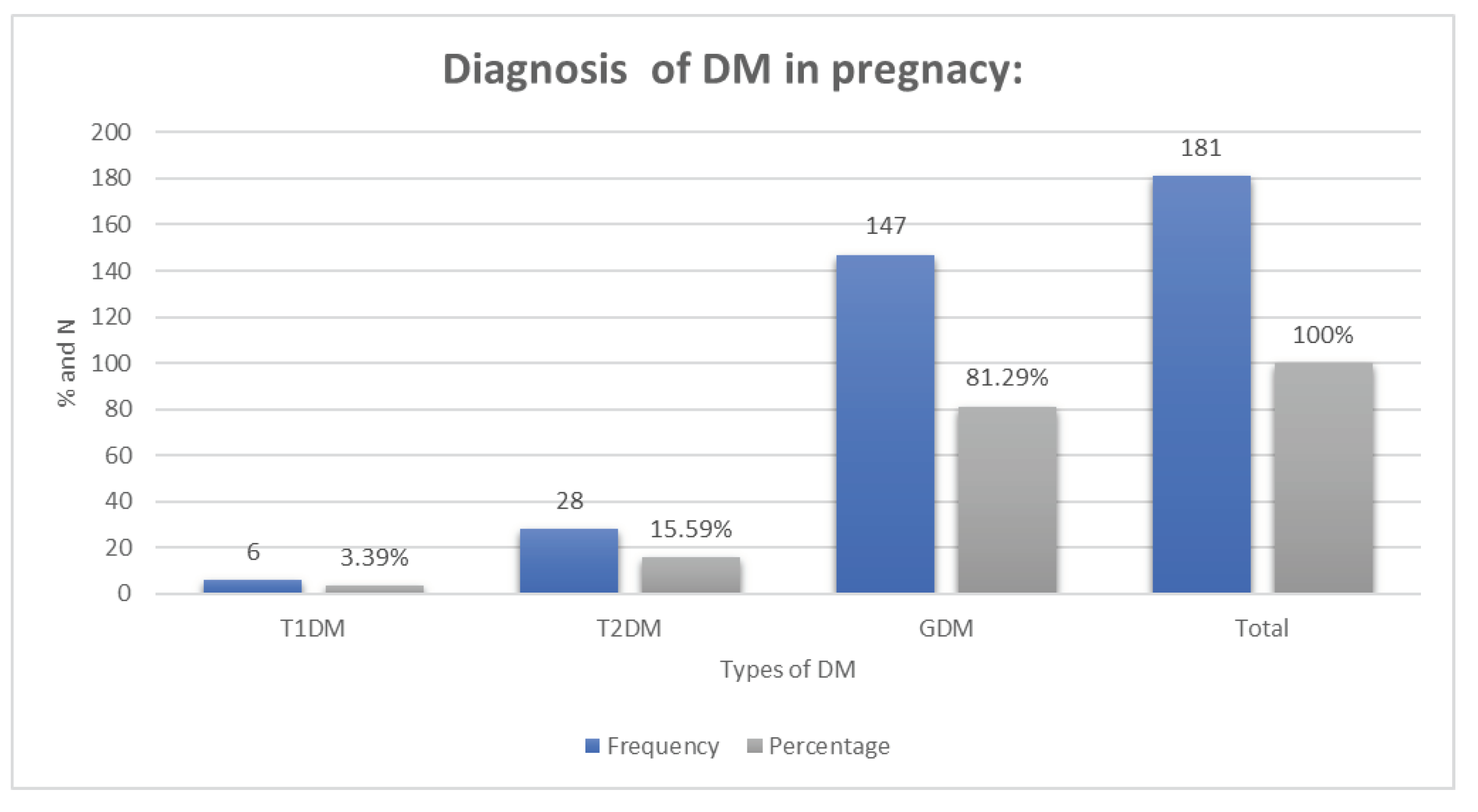

The frequency and percentage of the types of DM are described in Figure 2.

3.5. Logistics regression

Neonates born to mothers with MDM had a higher risk of adverse neonatal outcomes compared to those born to mothers without MDM (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 1.46, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.25-1.70). The risks of macrosomia (aOR = 1.74, 95% CI: 1.38-2.19), preterm birth (aOR = 1.32, 95% CI: 1.06-1.66), and respiratory distress syndrome (aOR = 1.57, 95% CI: 1.28-1.93) were significantly higher among neonates born to mothers with MDM as shown in Table 3.

4. Discussion

This study described the maternal characteristics and neonatal outcomes in 181 women. The main outcome of maternal diabetes is delivering neonates with surgical intervention. In the present study, most of the patients were delivered by CS in both GDM and pre-GDM. The outcomes of this study are supported by data gathered from other regions of the nation.

In the present study, GDM was more common than pre-GDM, and these results are supported by a study done in Saudi Arabia (SA) and India, which both showed that GDM was more common than pre-GDM [8,13]. The present study attempted to categorize pregestational diabetes into T1DM and T2DM. Pregestational T2DM was higher than T1DM, which agrees with previous reports [11] but differs from studies done in Scotland and Ireland, which showed that T1DM is more common than T2DM [14,15]. Due to the continuous elevation of GDM incidence result from the ongoing enrichment over time of risk factors of GDM such as obesity, advanced age pregnancy, or raised the number of births [16]. So, patients with pre-GDM or GDM should receive high attention from the healthcare provider to prevent the development of unfavorable outcomes.

In GDM, unexpected and different outcomes between this research and previous studies described that almost half of the patients delivered by CS and the other half delivered vaginally, but this differs from a study done in Saudi Arabia (SA) in which vaginal delivery was more common than CS [8,17,18,19]. In pre-GDM, unexpected and different outcomes between this study and previous studies described vaginal delivery as more common than CS [8,20]. It was also noted that that not all patients who undergo CS should be viewed as having unfavorable pregnancy outcomes; instead, CS is frequently suggested as a preventive measure used by healthcare professionals to reduce the risk of perinatal problems brought on by maternal diabetes [21]. So, in maternal diabetes, healthcare providers should use strategies and recommendations to prevent unfavorable outcomes.

Furthermore, in the present study, macrosomia was a more common adverse outcome associated with maternal diabetes than LBW. Additionally, macrosomia in GDM was more common than in LBW, and these results are supported by studies done in China and Qatar [22,23]. Both studies found macrosomia to be more common than LBW, but these are different from studies done in Saudi Arabia (SA) and Brazil that showed that birth weight in GDM is more common than in LBW than macrosomia [18,24]. In the present study, in pre-GDM, LBW is more common than macrosomia, which was expected, but this differs from the results of a study done in Italy that showed high association between macrosomia and pre-GDM [11]. As expected, women with all types of maternal diabetes were at risk of developing macrosomia or LBW. So, patients with pre-GDM or GDM should be careful of glycemic control, regular follow-up, and quick treatment for diabetic mothers to prevent developing macrosomia or LBW.

The present study evaluated different neonatal outcomes according to the types of maternal DM. The major neonatal outcomes of maternal DM included congenital heart disease, macrosomia, RDS, and NICU admission. The findings of this study are supported by data gathered from other studies of the nation. In the present study, in maternal diabetes, the most common neonatal finding was congenital heart disease; these results are supported by studies done in New York that showed congenital heart disease had a strong association with maternal diabetes and pre-GDM had a more significant association with congenital heart disease phenotypes and categories [25,26]. In this study, macrosomia was the most common neonatal finding related to GDM, which is supported by studies showing that GDM is associated with macrosomia [25,27]. Moreover, RDS was strongly associated with all types of maternal DM, which is supported by studies showing that GDM and pre-GDM had a greater association with RDS [26,28,29,30], and Sepsis was related to maternal diabetes, which is also supported by a study that showed greater concern between sepsis and maternal DM and hypertension [31]. In this research, association between maternal diabetes and neonatal death was found, which is supported by previous studies that had suggested an association with neonatal mortality [32] but is different from a study that showed no association between maternal diabetes and neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis, intraventricular hemorrhage, or neonatal death [33]. In the present study, admission to NICU was associated with GDM and pre-GDM, which is supported by studies showing a relation between GDM and pre-GDM and NICU admissions [18,33]. However, these results may agree or disagree with those of other studies because of variations in the patient groups investigated and advancements in neonatal care at delivery.

Currently, in Saudi Arabia, maternal diabetes is between 4.3% and 24.3% of all pregnancies [8]. With the growth of the public health burden of GDM and pre-GDM, clinical management must be informed by high-quality research to achieve the best possible outcomes for neonates. In this retrospective cohort, compared to GDM or no diabetes, maternal pre-GDM was linked to an increase in severe neonatal morbidity. In contrast, neonates born to mothers with pre-GDM are most at risk of severe neonatal morbidity and may still experience unfavorable outcomes, needing the greatest care throughout delivery.

The weakness of our study included its retrospective approach, while helpful in providing insights into past data, can be limited in terms of its ability to capture all relevant information. Additionally, the reliance on administrative data may not provide a complete picture of the outcomes for both mothers and neonates. The lack of information on maternal glycemic control is also a limitation as it can impact both maternal and neonatal outcomes. Without this data, it is challenging to draw any definitive conclusions on the relationship between maternal glycemic control and outcomes. Overall, it is important to consider these limitations when interpreting the results of the study and to be cautious in drawing conclusions based solely on the findings.

The strengths of our study included identifying important associations between GDM and pre-GDM with increased risk of neonatal mortality and morbidity. This provides valuable information for healthcare providers and policymakers to improve prenatal care and management of diabetes in pregnant women. Additionally, the study's large sample size and use of national administrative data provide a broad perspective on the issue and increase the generalizability of the findings.

The implication in practice is that healthcare providers should consider conducting a prospective study to evaluate diabetic women from their first visit to the time of delivery. This type of study would allow for a more comprehensive evaluation of maternal glycemic control and its relationship to both maternal and neonatal outcomes. Additionally, it would provide more accurate data on these outcomes and potentially identify interventions that could improve outcomes for mothers and neonates with GDM or pre-GDM. It is also important for healthcare providers to provide education and support to women with GDM or pre-GDM to help them manage their condition and minimize the risks associated with it.

5. Conclusions and recommendation

It is crucial for healthcare providers to identify and manage DM in pregnant women, as this can lead to improved maternal and neonatal outcomes. The findings of this study highlight the importance of closely monitoring and managing blood glucose levels in pregnant women with DM, in order to reduce the risk of adverse neonatal health outcomes such as macrosomia, NICU admission, LBW, and RDS. The study also emphasizes the need for further research to better understand the relationship between glycemic control and maternal and neonatal outcomes in women with DM during pregnancy. Overall, these findings have important implications for clinical practice and can inform the development of guidelines for the management of DM in pregnant women.

That is a very comprehensive and informative statement. Providing early and successful interventions, such as prenatal care and careful glycemic control, can greatly improve the outcomes for both the mother and the neonate. Screening every pregnant woman for pre-GDM and GDM can help identify those at risk early on and enable efforts to prevent their emergence. Educating pregnant women on the importance of maintaining adequate glycemic control and preventing the development of type 2 diabetes in GDM patients can also help reduce the impact of maternal diabetes on society. Overall, a multidisciplinary approach involving obstetricians, endocrinologists, and other healthcare professionals is necessary to improve outcomes in pregnant women with diabetes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Abdullah Alshomrany; Data curation, Abdullah Alshomrany; Formal analysis, Abdullah Alshomrany and Abdulmohsen Alshahrani; Funding acquisition, Elhadi Miskeen and Jaber Al-faifi; Investigation, Abdulmohsen Alshahrani; Methodology, Abdullah Alshomrany and Hassan Alshamrani; Project administration, Abdullah Alshomrany; Resources, Elhadi Miskeen and Hassan Alshamrani; Software, Hassan Alshamrani; Supervision, Jaber Al-faifi; Writing – original draft, Abdullah Alshomrany; Writing – review & editing, Elhadi Miskeen and Jaber Al-faifi.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval was obtained from Standing Committee for Scientific Research - University of Bisha College of Medicine (UBCOM) reviewed and approved the study, which was registered under the number (H-06-BH-087). This article does not involve any studies conducted on human participants or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the study’s findings are available from the corresponding author, [A. Alshomrany], upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to the MCH in Bisha, Saudi Arabia, for providing us with the opportunity to conduct this study. We also extend our appreciation to the medical records staff for their assistance in collecting all necessary data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cho NH, Shaw JE, Karuranga S, Huang Y, da Rocha Fernandes JD, Ohlrogge AW, Malanda BI. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. Diabetes research and clinical practice. 2018 Apr 1;138:271-81. [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes—2021. Diabetes care. 2021 Jan 1;44(Supplement_1):S15-33. [CrossRef]

- Prakash GT, Das AK, Habeebullah S, Bhat V, Shamanna SB. Maternal and neonatal outcome in mothers with gestational diabetes mellitus. Indian journal of endocrinology and metabolism. 2017 Nov;21(6):854. [CrossRef]

- Shahbazian H, Nouhjah S, Shahbazian N, Jahanfar S, Latifi SM, Aleali A, Shahbazian N, Saadati N. Gestational diabetes mellitus in an Iranian pregnant population using IADPSG criteria: Incidence, contributing factors and outcomes. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews. 2016 Oct 1;10(4):242-6. [CrossRef]

- Alqurashi KA, Aljabri KS, Bokhari SA. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus in a Saudi community. Annals of Saudi medicine. 2011 Jan;31(1):19-23. [CrossRef]

- Gojnic M, Todorovic J, Stanisavljevic D, Jotic A, Lukic L, Milicic T, Lalic N, Lalic K, Stoiljkovic M, Stanisavljevic T, Stefanovic A. Maternal and fetal outcomes among pregnant women with diabetes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022 Mar 20;19(6):3684. [CrossRef]

- Alsaedi SA, Altalhi AA, Nabrawi MF, Aldainy AA, Wali RM. Prevalence and risk factors of gestational diabetes mellitus among pregnant patients visiting National Guard primary health care centers in Saudi Arabia. Saudi medical journal. 2020 Feb;41(2):144. [CrossRef]

- Wahabi H, Fayed A, Esmaeil S, Mamdouh H, Kotb R. Prevalence and complications of pregestational and gestational diabetes in Saudi women: analysis from Riyadh Mother and Baby cohort study (RAHMA). BioMed research international. 2017 Oct;2017. [CrossRef]

- Gasim, T. Gestational diabetes mellitus: maternal and perinatal outcomes in 220 Saudi women. Oman medical journal. 2012 Mar;27(2):140. [CrossRef]

- Mitanchez D, Yzydorczyk C, Simeoni U. What neonatal complications should the pediatrician be aware of in case of maternal gestational diabetes? World J Diabetes. 2015; 6 (5): 734–43. [CrossRef]

- Gualdani E, Di Cianni G, Seghieri M, Francesconi P, Seghieri G. Pregnancy outcomes and maternal characteristics in women with pregestational and gestational diabetes: A retrospective study on 206,917 singleton live births. Acta Diabetologica. 2021 Sep;58:1169-76. [CrossRef]

- Behboudi-Gandevani S, Amiri M, Bidhendi Yarandi R, Ramezani Tehrani F. The impact of diagnostic criteria for gestational diabetes on its prevalence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetology & metabolic syndrome. 2019 Dec;11(1):1-8. [CrossRef]

- Anjum SK, Yashodha HT. A study of neonatal outcome in infants born to diabetic mothers at a tertiary care hospital. Int J Contemp Pediatr. 2018 Mar;5(2):489-92. [CrossRef]

- Mackin ST, Nelson SM, Kerssens JJ, Wood R, Wild S, Colhoun HM, Leese GP, Philip S, Lindsay RS. Diabetes and pregnancy: national trends over a 15 year period. Diabetologia. 2018 May;61(5):1081-8. [CrossRef]

- Ali DS, Davern R, Rutter E, Coveney C, Devine H, Walsh JM, Higgins M, Hatunic M. Pre-gestational diabetes and pregnancy outcomes. Diabetes Therapy. 2020 Dec;11:2873-85. [CrossRef]

- Seghieri G, Di Cianni G, Seghieri M, Lacaria E, Corsi E, Lencioni C, Gualdani E, Voller F, Francesconi P. Risk and adverse outcomes of gestational diabetes in migrants: A population cohort study. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2020 May 1;163:108128. [CrossRef]

- Muche AA, Olayemi OO, Gete YK. Effects of gestational diabetes mellitus on risk of adverse maternal outcomes: a prospective cohort study in Northwest Ethiopia. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2020 Dec;20(1):1-3. [CrossRef]

- Alfadhli EM, Osman EN, Basri TH, Mansuri NS, Youssef MH, Assaaedi SA, Aljohani BA. Gestational diabetes among Saudi women: prevalence, risk factors and pregnancy outcomes. Annals of Saudi medicine. 2015 May;35(3):222-30. [CrossRef]

- Ovesen PG, Jensen DM, Damm P, Rasmussen S, Kesmodel US. Maternal and neonatal outcomes in pregnancies complicated by gestational diabetes. A nation-wide study. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 2015 Sep 22;28(14):1720-4. [CrossRef]

- Kruit H, Mertsalmi S, Rahkonen L. Planned vaginal and planned cesarean delivery outcomes in pregnancies complicated with pregestational type 1 diabetes–A three-year academic tertiary hospital cohort study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2022 Mar 2;22(1):173. [CrossRef]

- Magro-Malosso ER, Saccone G, Chen M, Navathe R, Di Tommaso M, Berghella V. Induction of labour for suspected macrosomia at term in non-diabetic women: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2017 Feb;124(3):414-21. [CrossRef]

- Bayoumi MA, Masri RM, Matani N, Hendaus MA, Masri MM, Chandra P, Langtree LJ, D’Souza S, Olayiwola NO, Shahbal S, Elmalik EE. Maternal and neonatal outcomes in mothers with diabetes mellitus in Qatari population. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2021 Dec;21(1):1-1. [CrossRef]

- Li MF, Ma L, Yu TP, Zhu Y, Chen MY, Liu Y, Li LX. Adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes in pregnant women with abnormal glucose metabolism. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2020 Mar 1;161:108085. [CrossRef]

- Silva AL, Amaral AR, Oliveira DS, Martins L, Silva MR, Silva JC. Desfechos neonatais de acordo com diferentes terapêuticas do diabetes mellitus gestacional. Jornal de Pediatria. 2017 Jan;93:87-93. [CrossRef]

- Yang GR, Dye TD, Li D. Effects of pre-gestational diabetes mellitus and gestational diabetes mellitus on macrosomia and birth defects in upstate New York. Diabetes research and clinical practice. 2019 Sep 1;155:107811. [CrossRef]

- Hoang TT, Marengo LK, Mitchell LE, Canfield MA, Agopian AJ. Original findings and updated meta-analysis for the association between maternal diabetes and risk for congenital heart disease phenotypes. American journal of epidemiology. 2017 Jul 1;186(1):118-28. [CrossRef]

- He XJ, Qin FY, Hu CL, Zhu M, Tian CQ, Li L. Is gestational diabetes mellitus an independent risk factor for macrosomia: a meta-analysis?. Archives of gynecology and obstetrics. 2015 Apr;291:729-35. [CrossRef]

- Al-Qahtani, MH. Infants of diabetic mothers: 4 years analysis of neonatal care unit in a teaching hospital, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences. 2014 Sep 1;2(3):151. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Wang W, Zhang D. Maternal diabetes mellitus and risk of neonatal respiratory distress syndrome: a meta-analysis. Acta diabetologica. 2019 Jul 1;56:729-40. [CrossRef]

- Capobianco G, Gulotta A, Tupponi G, Dessole F, Virdis G, Cherchi C, De Vita D, Petrillo M, Olzai G, Antonucci R, Saderi L. Fetal Growth and Neonatal Outcomes in Pregestational Diabetes Mellitus in a Population with a High Prevalence of Diabetes. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2022 Aug 16;12(8):1320. [CrossRef]

- Birch MN, Frank Z, Caughey AB. Rates of neonatal sepsis by maternal diabetes and chronic hypertension [12D]. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2019 May 1;133:45S-4S. [CrossRef]

- Stacey T, Tennant PW, McCowan LM, Mitchell EA, Budd J, Li M, Thompson JM, Martin B, Roberts D, Heazell AE. Gestational diabetes and the risk of late stillbirth: a case–control study from England, UK. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2019 Jul;126(8):973-82. [CrossRef]

- Battarbee AN, Venkatesh KK, Aliaga S, Boggess KA. The association of pregestational and gestational diabetes with severe neonatal morbidity and mortality. Journal of Perinatology. 2020 Feb;40(2):232-9. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Histogram shows pregnant women's age with frequency.

Figure 2.

Clustered bar chart showing the frequency and percentage of the types of DM.

Table 1.

Maternal characteristics of the three groups.

| Maternal characteristics: | T1DM | T2DM | GDM | Total | p- Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nationality | Saudi | 6 | 26 | 136 | 168 (92.8%) | 0.056 |

| Non-Saudi | 0 | 2 | 11 | 13 (7.2%) | ||

| Region: | City (urban) | 5 | 24 | 119 | 148 (81.8%) | |

| Village (rural) | 1 | 1 | 24 | 26 (14.4%) | 0.076 | |

| Outside the region | 0 | 3 | 4 | 7 (3.9%) | ||

| Family history of diabetes | Yes | 0 | 7 | 33 | 40 (22.1%) |

0.061 |

| No | 6 | 21 | 114 | 141 (77.9%) | ||

| Time diagnosed DM | Before pregnancy (pre-GDM) | 6 | 28 | 0 | 34 (18.8%) |

0.010* |

| During pregnancy (GDM) | 0 | 0 | 147 | 147 (81.2%) | ||

| Number of pregnancies | 1-2 | 4 | 6 | 56 | 66 (36.5%) | |

| 3-4 | 2 | 13 | 61 | 76 (42%) | 0.074 | |

| More than 5 | 0 | 9 | 30 | 39 (21.5%) | ||

| Types of delivery | Vaginal | 0 | 1 | 8 | 9 (5%) | 0.049* |

| CS | 6 | 27 | 139 | 172 (95%) | ||

| History of neonatal death | Yes | 1 | 3 | 8 | 12 (6.6%) | 0.096 |

| No | 5 | 25 | 139 | 169 (93.4%) | ||

| Birth weight | <2.5 LBW | 5 | 5 | 11 | 21 (11.6%) | |

| 2.5-3.99 Normal | 1 | 20 | 107 | 128 (70.7%) | 0.078 | |

| ≥4 more than 4 kg (Macrosomia) | 0 | 3 | 29 | 32 (17.7%) |

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM); type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM); gestational diabetes malleus (GDM); Cesarean section (CS); low birth weight (LBW).

Table 2.

Neonatal outcomes of the three groups:.

| Neonatal outcome: | T1DM | T2DM | GDM | Total | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RDS | 2 | 3 | 11 | 16 (8.8%) | 0.102 | |

| Prematurity | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.6%) | 0.128 | |

| Hypoglycemia | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.6%) | 0.017* | |

| Congenital heart disease | 0 | 13 | 26 | 39 (21.5%) | 0.076 | |

| Development and Growth disorder | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 (1.1%) | 0.062 | |

| DM | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 (1.7%) | 0.073 | |

| LBW | 5 | 5 | 11 | 21 (11.6%) | 0.106 | |

| More than 4 kg (Macrosomia) | 0 | 3 | 25 | 28 (15.5%) | 0.050* | |

| Sepsis | 2 | 1 | 9 | 12 (6.6%) | 0.111 | |

| Neonatal death | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.6%) | 0.017* | |

| Normal | 1 | 9 | 77 | 87 (48.06%) | 0.066 | |

| Neonatal outcomes | Cure | 3 | 11 | 92 | 106 (59.6%) | |

| Died | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.6%) | 0.080 | |

| Developed complications then improve | 2 | 15 | 49 | 66 (36.5%) | ||

| Developed complication | 1 | 2 | 5 | 8 (4.4%) | ||

| NICU admission | 3 | 13 | 49 | 65 (35.9%) | 0.077 |

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM); type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM); gestational diabetes malleus (GDM); respiratory distress syndrome (RDS); diabetes mellitus (DM); low birth weight (LBW); neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).

Table 3.

Neonatal outcomes in MDM mothers and their prediction by logistic regression.

| Neonatal outcomes in MDM mothers: | Odd ratio (OR), 95% Confidence interval (CI) |

|---|---|

| Macrosomia | OR = 1.74, 95% CI: 1.38-2.19 |

| LBW | OR = 1.32, 95% CI: 1.06-1.66 |

| RDS | OR = 1.57, 95% CI: 1.28-1.93 |

Odd ratio (OR), 95% Confidence interval (CI), low birth weight (LBW), respiratory distress syndrome (RDS).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Copyright: This open access article is published under a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license, which permit the free download, distribution, and reuse, provided that the author and preprint are cited in any reuse.

Maternal Diabetes Mellitus and Neonatal Outcomes in Bisha: A Retrospective Cohort Study.

Abdullah Alshomrany

et al.

,

2024

Fetal Macrosomia and Associated Factors to Perinatal Adverse Outcomes, in Yaounde, Cameroon : A Case Control Study

Anne Esther Njom Nlend

et al.

,

2022

Fetal Macrosomia and Associated Factors to Perinatal Adverse Outcomes, in Yaounde, Cameroon : A Case Control Study

Anne Esther Njom Nlend

et al.

,

2022

MDPI Initiatives

Important Links

© 2024 MDPI (Basel, Switzerland) unless otherwise stated