Preprint

Case Report

IgA Nephropathy with Hepatitis B Infection: A Rare Case of Infection and Autoimmunity

Altmetrics

Downloads

121

Views

88

Comments

0

This version is not peer-reviewed

Submitted:

12 April 2024

Posted:

15 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Alerts

Abstract

Presenting a case report on the occurrence of IgA nephropathy with hepatitis B infection in a 32-year-old male patient with main complaints of generalized weakness, easy fatigue, and bilateral swelling of the lower extremities. IgA nephropathy (IgAN), or Berger’s disease, is the most common primary glomerulonephritis worldwide. It is characterized by the formation of IgA1-containing circulating immune complexes and their deposition in the glomerular mesangium. Its etiology remains multifactorial and often idiopathic. IgA nephropathy alone does not have an infectious etiology; instead, it usually develops in conjunction with an infectious condition that triggers a dysregulated immune response. There is no proof that any particular infectious agent is the secondary cause of IgA nephropathy. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is an infectious agent associated with renal complications, including IgA nephropathy. Symptoms include gross haematuria and mild proteinuria indicative of renal involvement. Laboratory investigations and serological tests are followed by imaging studies such as ultrasound and renal biopsy to confirm the diagnosis. The challenges encountered during the diagnostic process included overlapping symptoms and limitations of available diagnostic tests, highlighting the need for comprehensive diagnostic evaluation and multidisciplinary management approaches in similar cases. This case underscores the importance of recognizing and managing both conditions simultaneously to prevent long-term complications such as end-stage renal disease.

Keywords:

Subject: Medicine and Pharmacology - Immunology and Allergy

Introduction:

IgA nephropathy (IgAN), or Berger’s disease, is the most common primary glomerulonephritis worldwide. It is characterized by the formation of IgA1-containing circulating immune complexes and their deposition in the glomerular mesangium. Although the disease is more common in some nations than others, the pathogenic pathways are still mostly unknown [1,2].

Elevated levels of galactose-deficient Gd-IgA1 act as autoantigens and trigger the production of specific glycan autoantibodies, resulting in the formation of immune complexes containing IgA1 (IgA1-IC), some of which deposit in the kidneys, particularly in the glomerular mesangium. So, Gd-IgA1 (1st hit), endogenous anti-glycan antibodies (2nd hit), and subsequent formation of immune complexes (3rd hit) and glomerular depositions (4th hit [3]. These complexes then induce glomerular injury through pro-inflammatory cytokine release, chemokines, and migration of macrophages into the kidney.

Although its etiology remains multifactorial and often idiopathic, associations with various infections have been documented. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is an infectious agent associated with renal complications, including IgA nephropathy. Furthermore, genetic predispositions and environmental factors can influence the development and progression of IgA nephropathy in the context of HBV infection, further complicating the pathophysiology of the disease. Recent retrospective research revealed clinicopathological distinctions between primary IgAN without HBV infection and IgAN positive for the surface antigen for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) [4]. An independent risk factor for the progression of IgAN is hepatitis B infection [5].

The presented case report highlights the clinical complexity of IgA nephropathy with concurrent HBV infection, highlighting the importance of early recognition and comprehensive management. Clinically, patients may present with a spectrum of renal manifestations, ranging from asymptomatic microscopic hematuria to overt nephrotic syndrome and rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis. Therefore, a high index of suspicion of underlying HBV infection should be maintained in patients with IgA nephropathy, especially in endemic regions or individuals at increased risk of viral exposure.

Case presentation:

A 32-year-old man from a lower socioeconomic class was presented in the outpatient department with his wife with the principal complaints of generalized weakness, easy fatigue, and bilateral swelling of the lower extremities for 15-20 days. The patient was relatively asymptomatic before 20 days, after which he noticed swelling around both ankles that was progressive. It was associated with easy fatigability in his daily chores. It was not associated with micturition pain or facial puffiness, and there was no increase or decrease in urinary frequency. There was no history of fever, headache, dizziness, vomiting, or breathlessness.

There was no history of sore throat, joint pain, rashes, weight loss, or any recent illness.

Past history:

No history of any respiratory disease, GI disease, hypertension, or thyroid disease. No history of palpitation, syncope, difficulty breathing with or without exertion, or chest pain.

Physical examination:

Physical examination showed a normal temperature, pulse rate of 78/min, blood pressure of 170/100mmHg, SpO2 99% in room air, and RBS of 110 mg/dl. The respiratory examination showed a respiratory rate of 16/min and an equal air entry bilateral was present. S1S2 was present on the cardiovascular examination.

On general examination, the patient was conscious and oriented to time, place, and person.

Examination revealed moderate bilateral pitting pedal edema up to the ankle.

Lab investigations:

Blood examination revealed a hemoglobin level of 11.7 g/dL (normal range > 12.0 g/dL) with normal leukocyte count and platelet count (Table 1). The renal function test revealed blood urea levels of 84 mg/dl (normal range < 45 mg/dl) and serum creatinine levels of 2.05 mg/dl (normal range <1.1 mg/dl) with normal serum sodium and potassium levels (Table 2). The liver function tests were in the normal range with serum albumin of 3.3 g/dl (normal range >3.4 g/dl) (Table 3). Urine examination showed albumin 2 +, blood 1 + with RBC 6-8 / hpf, and granular casts in urine (Table 4).

Further investigations showed, that urine albumin creatinine ratio: 288mg/g (normal <30 mg/g), 24-hour urine protein: 2100mg/day (normal <150 mg/day), 24-hour urine creatinine: 647 (normal: 800-2000) and eGFR; 45ml/min/1.73m2 (normal 116ml/min/1.73m2).

Radiological Investigations:

- (1)

- The USG abdomen revealed that the kidneys with increased B / L corticogenicity, with preserved corticomedullary differentiation. The liver showed normal echotexture

- (2)

- Renal Doppler revealed an increase in the acceleration index at all poles suggesting early renal parenchymal disease.

- (3)

- 2D echo revealed grade 1 diastolic dysfunction.

The examination of serum markers showed a positive surface antigen for hepatitis B with HBV DNA having 3 * 10 3 copies (in the linear range) and a negative antigen for hepatitis e (Table 5). The serum antinuclear antibody (ANA) test and the antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) test were negative.

As advised during the hospital stay, the patient underwent a kidney biopsy, revealing the presence of IgA nephropathy.

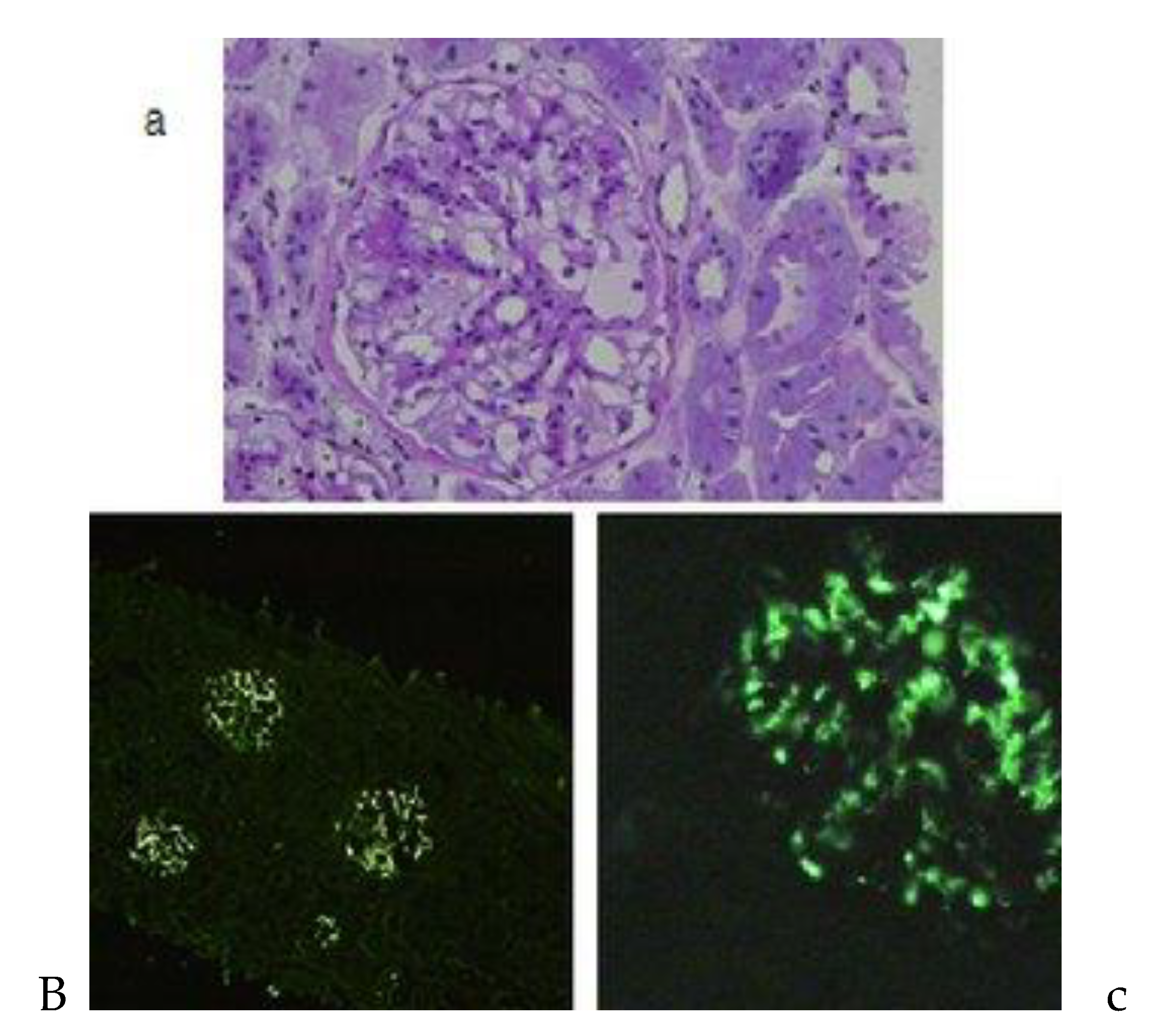

Histopathology of IgA nephropathy: (a) Light microscopy showing a glomerulus with increased segmental in the mesangial matrix and mild hypercellularity. (b) Immunofluorescent microscopy showing diffuse IgA deposits in all glomeruli. (c) Immunofluorescent microscopy showing generalized mesangial IgA deposits within the entire surface/volume of the glomerulus [6].

Management:

The patient was treated with angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) and calcium channel blocker (CCB). ARB included a tablet of losartan 50 mg once a day and CBB included a tablet of clonidine 10 mg once a day for 10 days during the hospital stay of the patient. A tablet of calcium, vitamin D3, and sodium bicarbonate (500 mg once a day) was administered for supportive management. The patient was advised to restrict sodium in their diet, quit smoking, control weight, and exercise. The patient's condition gradually improved after 10 days and was discharged thereafter. ARBs, CCBS, calcium, and vitamin D3 supplements continued even after discharge. In our case, the viral load of HBV was low, and therefore no active treatment was considered.

Follow-up:

This patient was followed up after 20 days and there has been no recurrence or increase in blood pressure or general condition.

Diagnosis:

The patient was diagnosed with IgA nephropathy with hepatitis B infection based on the clinical presentation, imaging results, and response to antihypertensive therapy.

Discussion:

IgA nephropathy (IgAN), also known as Berger’s disease, is the most common primary glomerulonephritis in many parts of the world. While most people experience a relatively benign course of the disease, throughout 30 to 40 years, up to 40% of patients develop end-stage renal disease (ESRD) [7]. It is now generally acknowledged that multiple sequential but distinct pathogenic "hits" lead to the development of IgAN rather than a single pathogenic "hit." These "hits" primarily include increased levels of poorly O-galactosylated IgA1 glycoforms, the production of O-glycan-specific antibodies, and the formation of immune complexes containing IgA1. Glomerular damage is the result of the subsequent deposition of immune complexes containing IgA1 in the glomerular mesangium, which promotes cell proliferation and excessive synthesis of cytokines, chemokines, and extracellular matrix. The "multihit" hypothesis is the name given to the current theory of the pathophysiology of IgAN [3].

Its pathogenesis is still complex and sometimes idiopathic, but there is evidence of connections with several infections. The surface antigen for hepatitis B (HBsAg) is more common in IgAN in endemic areas, according to some authors, indicating that HBsAg is important in the pathophysiology of IgAN [8]. In contrast, several researchers have noted that the pathophysiology of IgAN is not related to HBs antigenemia and that there is no elevated prevalence of HBs antigenemia in patients with IgAN [9]. IgA nephropathy associated with hepatitis B surface antigen (HBs-IgAN) is thought to be initiated by mesangial and subendothelial entrapment of circulating immune complexes and subendothelial deposits, according to researchers who propose a substantial correlation between IgAN and HBs antigenemia[10,11,12] Why some chronic HBsAg carriers develop membranous glomerulonephritis (MGN) or mesangiocapillary glomerulonephritis (MCGN) while others get IgAN is still a mystery[13]. The size and charge characteristics of HBV antigens and their antibodies, as well as the status of HBV antigens, are all closely tied to this [1].

IgAN most commonly manifests itself as persistent asymptomatic microscopic hematuria or repeated episodes of macroscopic hematuria during or immediately after a URTI. Associated symptoms such as B / L pitting pedal edema, fatigue, and general weakness may be present.

Laboratory findings include elevated serum creatinine levels and urinary protein consistent with impaired renal function and proteinuria. Serological testing confirms the presence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), supporting the diagnosis of hepatitis B infection, while immunological tests may reveal elevated levels of IgA antibodies that support the diagnosis of IgA nephropathy.

Imaging studies such as ultrasound or renal biopsy can further support the diagnosis by revealing structural abnormalities or evidence of glomerular inflammation in the kidneys. The expansion of the extracellular matrix and the widespread or localized proliferation of the mesangial are the most frequently observed light microscopy findings [14]. Mesangial hypercellularity and excess mesangial matrix are seen by electron microscopy. Mesangial electron-dense IgA deposits are a significant finding; however, deposits in the subepithelial and subendothelial glomerular capillary wall are only observed in a small percentage of patients, especially those with the more severe form of the disease [15]. Mesangial IgA deposits are seen as a diffuse granular pattern using immunofluorescence, which is the hallmark of the disease [2].

The diagnostic process can be challenging due to the overlap of symptoms and the limitations of available diagnostic tests. First, the presentation of IgA nephropathy and hepatitis B infection with symptoms such as hematuria, proteinuria, and fatigue posed a diagnostic challenge, as these manifestations could be attributed independently to either condition. Additionally, the limitations of available diagnostic tests added complexity to the diagnostic workup. Although serological tests confirmed the presence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and supported the diagnosis of hepatitis B infection, there were no specific serological markers available to definitively diagnose IgA nephropathy. Furthermore, renal biopsy, while valuable for confirming IgA nephropathy, carries inherent risks and may not always be feasible or conclusive. Therefore, navigating through these overlapping symptoms and relying on a combination of clinical, laboratory, and imaging findings posed significant challenges in accurately diagnosing and managing both conditions in this patient.

The mainstay of therapy is blood pressure control, as in all glomerular disorders. During IgA nephropathy, blood pressure increases. Currently, proteinuria greater than 0.75–1 g/d in IgAN patients is considered to be a high risk of progression, even after 90 days of optimal supportive treatment. Immunosuppressive medications must be reserved for patients with IgAN who continue to have a high risk of progression of the disease [16]. Initial therapy with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi) or an angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) is recommended if the patient has proteinuria greater than 0.5 grams per day. In our case, the viral load of HBV was low so no active management was considered. Cases of florid ESRD requiring dialysis are rare [17].

In conclusion, the poor prognosis of IgAN is due in part to the delayed diagnosis. Due to multifactorial pathophysiology, the clinical presentation of IgAN is variable, ranging from mild forms with minor urinary abnormalities and preserved renal function to cases that rapidly progress to end-stage renal failure. Early risk stratification and individualized therapies would be desirable for patients with IgAN. Patients usually recover without complications.

Funding

None of the authors are financially interested in any of the products, devices, or drugs mentioned in this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical Statement

Being a case report study, there were no ethical issues and the IRB was notified about the topic and the case. Still, no formal permission was required as this was a record-based case report. Permission from the patient for the article has been acquired and ensured that their information or identity is not disclosed.

References

- Y. Endo and H. Kanbayashi. Etiology of IgA nephropathy syndrome. Pathol Int, vol. 44, no. 1, pp. 1–13, Jan. 1994. [CrossRef]

- J. H. Galla. IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int vol. 47, no. 2, pp. 377–387, Feb. 1995. [CrossRef]

- H. Suzuki et al., “The Pathophysiology of IgA Nephropathy,” Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, vol. 22, no. 10, pp. 1795–1803, Oct. 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. Gao et al., “Hepatitis B Virus Status and Clinical Outcomes in IgA Nephropathy,” Kidney Int Rep, vol. 9, no. 4, pp. 1057–1066, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Wang et al., “Clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis of hepatitis B associated membranous nephropathy and idiopathic membranous nephropathy complicated with hepatitis B virus infection,” Sci Rep, vol. 11, no. 1, p. 18407, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. Berthoux and A. Kamal, “Primary IgA Nephropathy: An Update in 2011,” in An Update on Glomerulopathies - Clinical and Treatment Aspects, InTech, 2011. [CrossRef]

- S. C. Yeo, C. K. Cheung, and J. Barratt, “New insights into the pathogenesis of IgA nephropathy,” Pediatric Nephrology, vol. 33, no. 5, pp. 763–777, May 2018. [CrossRef]

- K. N. Lai, F. M. Lai, J. S. Tam, and J. Vallance-Owen, “Strong association between IgA nephropathy and hepatitis B surface antigenemia in endemic areas.,” Clin Nephrol, vol. 29, no. 5, pp. 229–34, May 1988.

- H. Iida, K. H. Iida, K. Izumino, M. Asaka, M. Fujita, M. Takata, and S. Sasayama, “IgA Nephropathy and Hepatitis B Virus,” Nephron, vol. 54, no. 1, pp. 18–20, 1990. [CrossRef]

- Y. Endo and H. Kanbayashi, “Etiology of IgA nephropathy syndrome,” Pathol Int, vol. 44, no. 1, pp. 1–13, Jan. 1994. [CrossRef]

- J. Barratt, J. Feehally, and A. C. Smith, “Pathogenesis of IgA nephropathy,” Semin Nephrol, vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 197–217, May 2004. [CrossRef]

- J. H. Galla, “IgA nephropathy,” Kidney Int, vol. 47, no. 2, pp. 377–387, Feb. 1995. [CrossRef]

- N.-S. Wang, “Existence and significance of hepatitis B virus DNA in kidneys of IgA nephropathy,” World J Gastroenterol, vol. 11, no. 5, p. 712, 2005. [CrossRef]

- J. R. Hassler, “IgA nephropathy: A brief review,” Semin Diagn Pathol, vol. 37, no. 3, pp. 143–147, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. Kusaba et al., “Significance of broad distribution of electron-dense deposits in patients with IgA nephropathy,” Med Mol Morphol, vol. 45, no. 1, pp. 29–34, Mar. 2012. [CrossRef]

- G. Gharavi et al., “IgA nephropathy, the most common cause of glomerulonephritis, is linked to 6q22–23,” Nat Genet, vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 354–357, Nov. 2000. [CrossRef]

- Z. Chen et al., “The relation between dialysis-requiring acute kidney injury and recovery from end-stage renal disease: a national study,” BMC Nephrol, vol. 20, no. 1, p. 342, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Blood Examination:.

| Test | Observed Value | Reference Range |

|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin | 11.7 g/dl | (12-18 g/dl) |

| WBC | 7.5 kU/L | (5.2-12.4 KU/L) |

| Hematocrit | 35.8% | (40-50) |

| Platelet counts | 123 kU/L | (130-400 KU/L) |

Table 2.

Renal Function Test:.

| Test | Observed Value | Reference Range |

|---|---|---|

| Blood Urea | 84.0 mg/dl | (15-45 mg/dl) |

| Creatinine serum | 2.05 mg/dl | (0.5-1.1 mg/dl) |

| Sodium serum | 135 mmol/L | (132-146 mmol/L) |

| Potassium serum | 3.8 mmol/L | (3.5-5.5 mmol/L) |

Table 3.

Lipid profile:.

| Test | Observed Value | Reference Range |

|---|---|---|

| Total cholesterol | 188 mg/dL | (<200 mg/dl) |

| LDL cholesterol | 97 mg/dL | (<130 mg/dl) |

| SGPT | 42 U/L | (0-40 U/L) |

| Serum Albumin | 3.3 g/dl | (3.4-5.4 g/dl) |

Table 4.

Urine routine:.

| Test | Observed Value | Reference Range |

|---|---|---|

| Specific gravity | 1.020 | (1.005-1.030) |

| pH | 6 | (4.6-8) |

| Urine Albumin | ++ | negative |

| Urine Blood | + | negative |

| Granular cast | + | none seen |

| Uirne RBC | 6-8/hpf | 0-2/hpf |

Table 5.

Hepatitis panel:.

| Test | Observed Value | Reference Range |

|---|---|---|

| HBsAg | Positive | Negative |

| HBeAg | Negative | Negative |

| HBV DNA | 3*10^3 copies | < = 0.0 copies |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Copyright: This open access article is published under a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license, which permit the free download, distribution, and reuse, provided that the author and preprint are cited in any reuse.

Immune Responses of Anti-HCV Antibody after Direct-Acting Antiviral Therapy Associated Allograft Injury with Acute Jaundice in Patients underwent Liver Transplantation

Shu-Hsien Lin

et al.

,

2023

IGA‐Nephropathy in Northeastern Europe: Clinical and Morphological Presentation and Outcomes

Tatyana Muzhetskaya

et al.

,

2023

Membranous Glomerulonephritis: A Retrospective Study on Prognostic Outcome

Sadiq Maifata

et al.

,

2022

MDPI Initiatives

Important Links

© 2024 MDPI (Basel, Switzerland) unless otherwise stated