Preprint

Article

Michelangelo Effect in Cognitive Rehabilitation: Using Art in a Digital Visuospatial Memory Task

Altmetrics

Downloads

85

Views

28

Comments

0

A peer-reviewed article of this preprint also exists.

This version is not peer-reviewed

Submitted:

16 April 2024

Posted:

16 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Alerts

Abstract

Previous studies reported a reduction of the perceived effort and an improvement of the perfor-mances of healthy subjects and patients when a motor task was combined with artistic images with respect to non-artistic images. This phenomenon, called Michelangelo effect, could contribute to the efficacy of art therapy in neurorehabilitation. In this study, the possible occurrence of this effect was tested in a cognitive task by asking to 15 healthy subjects and 17 patients with stroke to solve a digital version of the classical memory card game. Three different types of images were used in a randomized order: French cards, artistic portraits, and photos of famous people (to compensate the possible effects of face recognition). Healthy subjects were involved to test the usability and the load demanding of the developed system, reporting no statistically significant differences among the three sessions (p > 0.05). Conversely, patients had a better performance in terms of time (p = 0.014) and number of trials (p = 0.007) needed to complete the task in presence of artistic stimuli, accompanied by a reduction of the perceived effort (p = 0.033). Furthermore, artistic stimuli, with respect to the other two types of images, seemed more associated to visuo-spatial control than to linguistic functions.

Keywords:

Subject: Public Health and Healthcare - Physical Therapy, Sports Therapy and Rehabilitation

1. Introduction

Since the beginning of the 21st century, there has been a major increase in research into the effects of the arts on health and well-being. The World Health Organization reported scientific evidences from a wide variety of studies using diverse methodologies about the potential impact of art on both mental and physical health [1]. This is mainly due to the aesthetic, cognitive, sensorial, perceptive and emotive engagement that art could evocate in a person [1]. Some studies showed a wide brain arousal, even involving motor cortex, during the observation of an artistic painting [2,3,4]. These activations during the observation of an artistic masterpiece could be exploited by the art therapy. Art therapy has two conventional approaches: based on art fruition (such as viewing of paintings, listening to music, usually using masterpieces) or based on art production (such as painting or playing an instrument, despite the products cannot be properly defined as art) [1]. However, thanks to new technologies the patient could be asked to actively produce an art product having the illusion to have generated a masterpiece. This is the case of a study in which the movements of the hand of patients with stroke were sonificated transforming the kinematics in sound [5]. If the movements were physiologically harmonious the acoustic feedback was a pleasant music, conversely, a dystonic movement produced a distorted sound. The virtual reality was used in a protocol of art therapy based on paintings in which the patient had the illusion of being able to replicate an artistic masterpiece such as the Creation of Adam of Michelangelo or the Birth of Venus of Botticelli [6]. In this study it was found that, during virtual painting, patients perceived less fatigue and had a better kinematic performance when they had the illusion to generate an artistic painting in respect to when they simply painted a virtual canvas: this outcome was called “Michelangelo Effect”. In a follow-up study, it was proven that the effect was mainly related to the replication of the painting than to the beauty of the stimulus [7]. In a randomized controlled trial, patients with stroke benefitted more of this virtual painting protocol based on Michelangelo Effect than of conventional physical therapy [8].

Despite in these studies it was hypothesized that at the basis of the Michelangelo effect there was a cognitive engagement of patients that increased their motivation, this effect was exploited more in neuromotor rehabilitation than on cognitive rehabilitation. Cognitive rehabilitation in stroke is often focused on the recovery of memory, attention, executive functions [9] and the many recent protocols use technological devices such as tablets and computers with specifically developed apps or software utilizing a gamified approach with serious exergame [10]. One of the most utilized and simple serious game is the “memory card”, in which the patient should remember the positions of cards to make pairs with the aim of a visuospatial memory training [9,11,12]. Digital memory card game was used also for rehabilitation in cerebral palsy [13]. Real or virtual cards could be used, usually French-suited cards with the four signs: hearts, clubs, diamonds and spades. For children, cards often report the images of animals or cartoons.

The aim of this study was to test the usability of a memory card game in patients with stroke based on the Michelangelo effect, in which conventional cards have been compared to images of artistic masterpieces and also to pictures of quite famous tv people. The last group of images was chosen to compensate the possible effects of familiarity (of famous paintings) and of (painted) face recognition that activates other brain circuits with respect to abstract signs of the French-suited cards [7,14,15].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Memory Serious Exergame

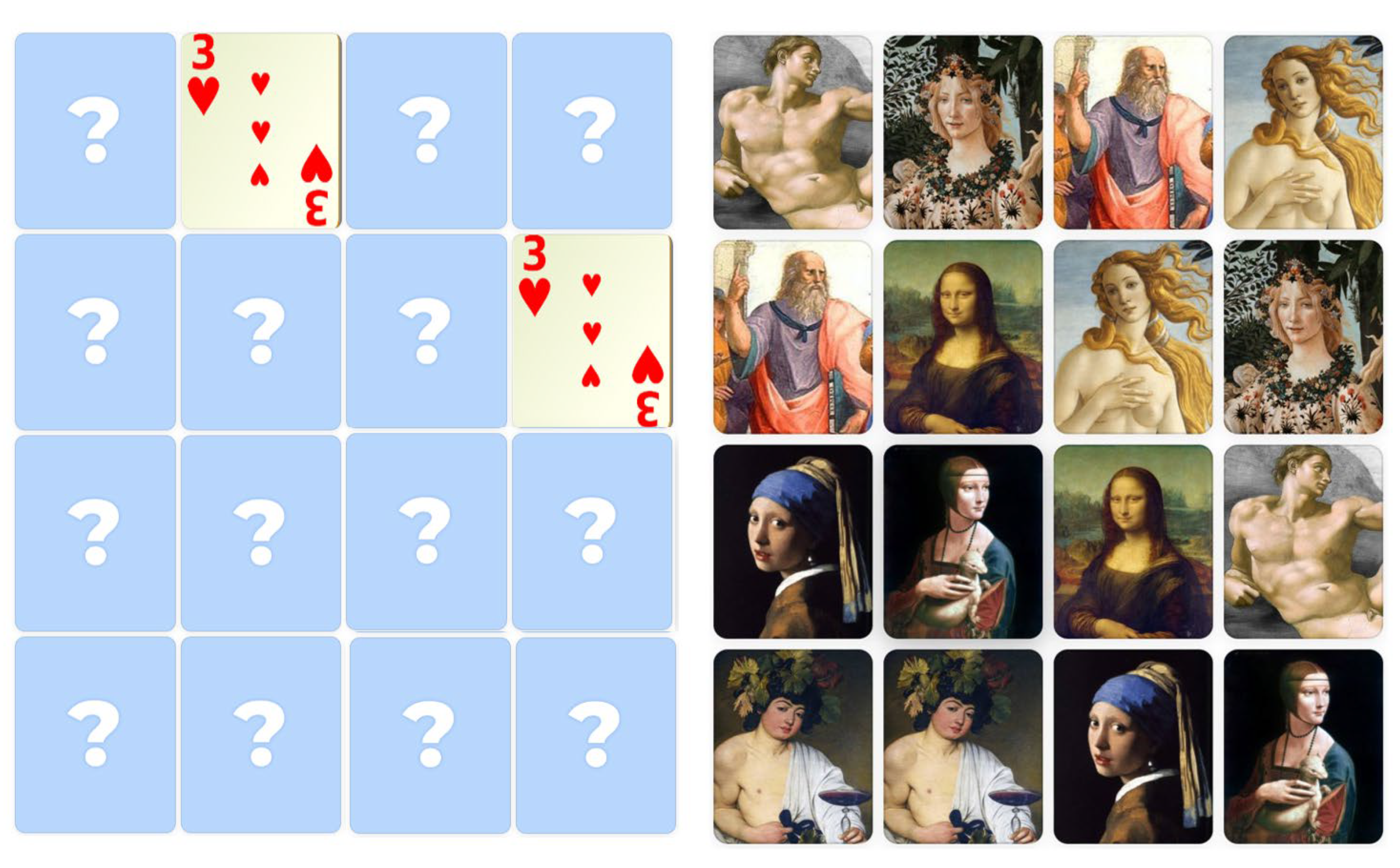

We developed a digital version of the “memory card” game to be performed on a touchscreen tablet (9.7 inches, resolution 2048*1536) similar to previous versions of digital memory card games [10,13]. Sixteen cards were used for each session placed on 4 rows and 4 columns. The game started with all the cards faced down and the player was instructed to turn over two cards by clicking on them. If the two cards showed the same picture, then the cards remained turned over, otherwise the cards returned faced down. The system recorded the time and the number of trials needed to complete the task, which consisted of pairing all the couples of cards. The three different versions of cards, (each presented in separated sessions) consisted of French cards, pictures of famous tv-news journalists of national channels, and portraits of characters from famous paintings. More specifically, portraits represented: Adam from the Creation of Adam (Michelangelo), Plato from the School of Athens (Raffaello), Venus from the Birth of Venus (Botticelli), Flora from the Primavera (Botticelli), Mona Lisa (Leonardo), the lady with an ermine (Leonardo) the girl with a pearl earring (Vermeer), and Bacchus (Caravaggio). The position of the images in each session was randomized.

2.2. Experiment 1: Usability of the System

Fifteen healthy adults (mean age: 27±6 years, 9 females) without neurological, cognitive, or orthopaedic diseases have been enrolled in this first experiment. They were asked to complete the task with their preferred hand and using their glassess if needed.

They performed three sessions (session order was counterbalanced across subjects) of the digital game: french cards, photos of famous people (television giornalists), and images of artistics paintings related to the Renaissance (Figure 1).

Similarly to previous studies on computerized serious games developed for rehabilitation [6,16,17,18,19], User Satisfaction Evaluation Questionnaire (USEQ) and Nasa Task Load Index (NASA-TLX) were administered to subjects after the completion of each session. Both scales test six domains of the self-perception concerning the usability and the perceived load demand of the tool. In particular, USEQ has six questions (for example: “Did you enjoy your experience with the system?”) and responses can be provided using a five-point Likert Scale, from 1 to 5. The six items test the experienced enjoyment, perceived successful use, ability to control, clarity of information, discomfort, and self-perceived utility about the performed exercise for rehabilitation. NASA-TLX has six questions with a ten point numerical rating scale for each one of the item (for example: “How physically demanding was the task?”). It tests the self-perceived mental demand, physical demand, time pressure, perceived success, fatigue, and stress.

2.3. Experiment 2: Tests on Patients

Seventeen patients with stroke (mean age: 65±15 years, 9 females, time from acute event: 23±18 days, 11 ischemic stroke, 11 stroke on the right hemisphere) have been enrolled in the second experiment of this study according to the following inclusion criteria: age ranging between 18 and 85, clinical diagnosis of stroke confirmed by computerized axial tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, a cognitive level adequate to understand the required instructions (Mini-Mental State Examination > 24), absence of unitaleral spatial neglect, absence of visual impairments that could be not corrected with glasses. They were asked to complete the task with the less affected hand and using their glasses if needed. Before the experiment with the tablet, patients were assessed using the tests of the Oxford Cognitive Screen [20]. The Italian version and the data interpretation reported by Iosa and colleagues [21] were used.

2.4. Ethical Approval and Informed Consent

The study was approved by Independent Local Ethical Committee and all the healthy subjects and the patients signed the informed consent.

2.5. Statistical Analyses

Data are reported in terms of mean ± standard deviation. Repeated measures analysis of variance (RM-Anova) was used to compare within-group the measured variables among paintings, photos and cards. Greenhouse-Geisser correction was used to compensate any possible violations of the RM-Anova assumptions, and Tukey correction was applied to p-values for post-hoc tests. The correlation coefficient R was used to compute the association between variables. For patients the correlation was also tested with the following clinical variables: items 3 and 5 of the MMSE, related to working memory and short-term memory (word repetition and word recall), and the tests of OCS covering the following tasks (domains): picture naming (memory), picture pointing (visuospatiol control), spatio-temporal location (orientation), sentence reading (language and arithmetics), number calculation (language and arithmetics), sentence recalling (memory), figure recall (memory). The alpha level of statistical significance associated to the rejection of the null hypothesis was fixed at 0.05 for all tests.

3. Results

3.1. Experiment 1: Usability of the System

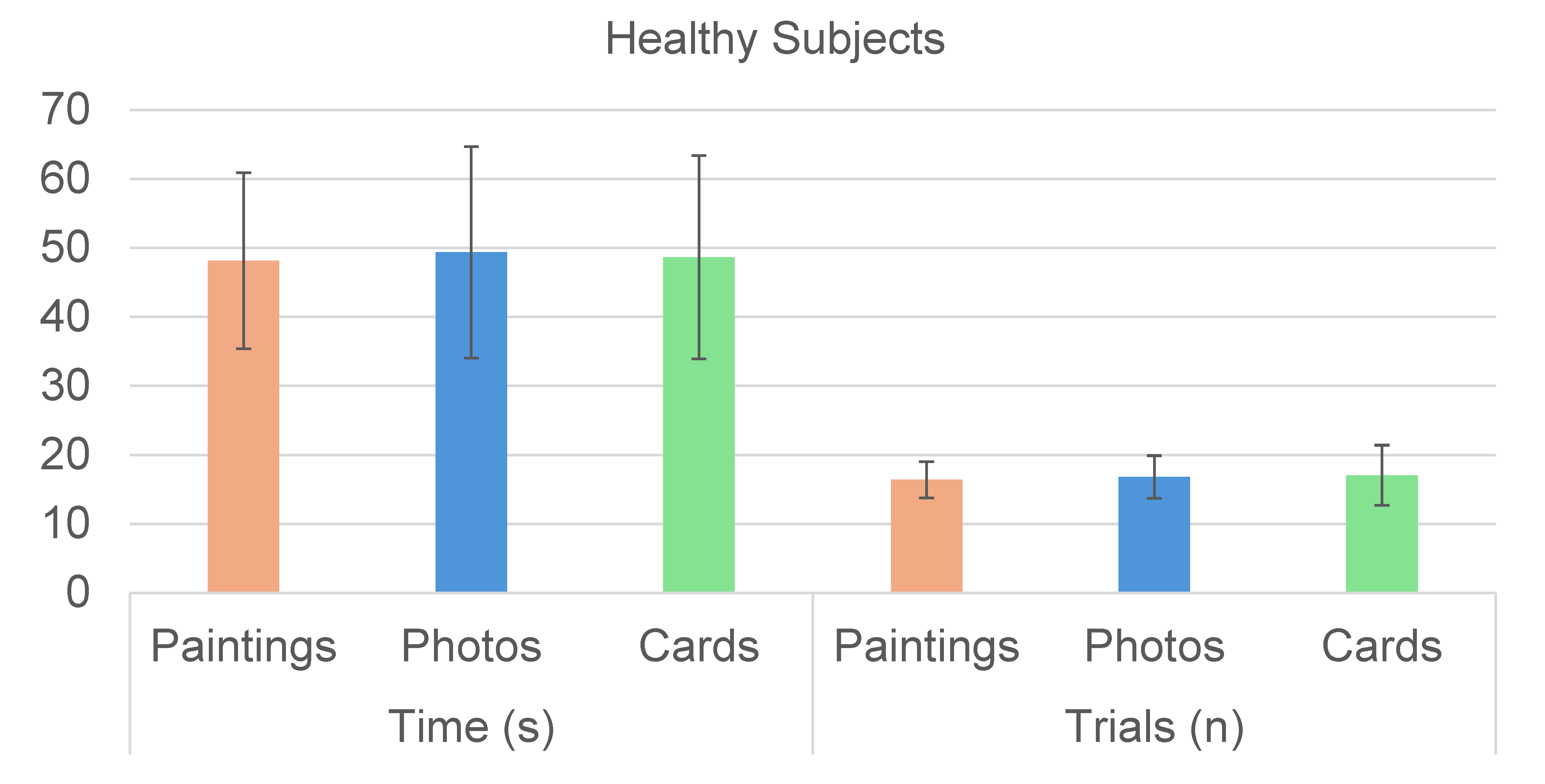

Figure 2 shows the time spent and the trials needed to complete each sessions of the memory task for healthy subjects. Neither time (F(2,14) = 0.04, p = 0.926, η p 2 = 0.003) nor number of trials (F(2,14) = 0.23, p = 0.789, η p 2 = 0.016) significantly varies among sessions.

Table 1 reports the scores of USEQ and NASA-TLX for healthy subjects. No significant differences were observed among the three sessions (p > 0.28 for all the items of USEQ and p > 0.14 for all the items of NASA-TLX). For all the three types of sessions the tasks resulted more mentally than physically demanding (p < 0.005).

3.2. Experiment 2: Tests on Patients

Also patients reported higher levels of usability assessed by USEQ with a low discomfort. No significant differences were noted among the three sessions. In terms of NASA-TLX, despite as expected patients required more time and trials to complete the task, their USEQ scores were similar to those of healthy subjects, and the differences were not statistically significant for any of these scores. In terms of NASA-TLX, a statistically significant difference was observed in terms of the effort reported by patients, with less fatigue associated to complete the task with paitings compared to that reported for cards or photos of famous people (F(2,14) = 3.98, p = 0.033, η p 2 = 0.199).

This difference reflected that measured among the three performances and shown in Figure 3. Patients required less time (F(2,14) = 4.93, p = 0.014, η p 2 = 0.236) and less number of trials (F(2,14) = 7.86, p = 0.007, η p 2 = 0.329) to complete the task with artistic pictures. Post-hoc tests highlighted that these results were mainly due to a difference in time between paintings and cards (p = 0.025, where no difference was observed between photos and cards: p = 0.410), and in trials of both paintings and photos with respect to cards (p = 0.025 and p = 0.023, respectively).

Table 2.

Mean ± standard deviation of the items of USEQ and of NASA-TLX for patients, with F-values (and relevant degrees of freedom), p-values and partial eta squared (η p 2) as results of the RM-Anova.

Table 2.

Mean ± standard deviation of the items of USEQ and of NASA-TLX for patients, with F-values (and relevant degrees of freedom), p-values and partial eta squared (η p 2) as results of the RM-Anova.

| Patients | Paintings | Photos | Cards | F(2,14) | p-value | η p 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USEQ | Experienced enjoyment | 4.8± 0.6 | 4.6± 0.6 | 4.6±0.6 | 2.55 | 0.108 | 0.137 |

| Successful use | 4.3±1.0 | 4.4±1.1 | 4.3±1.2 | 0.08 | 0.794 | 0.005 | |

| Ability to control | 4.6±0.8 | 4.5±0.9 | 4.5±0.9 | 2.13 | 0.135 | 0.118 | |

| Clarity of information | 4.9± 0.2 | 4.9±0.2 | 4.9±0.2 | 0.01 | 0.999 | 0.001 | |

| Discomfort | 1.0±0.2 | 1.1±0.3 | 1.2±0.4 | 2.55 | 0.108 | 0.137 | |

| Perceived utility | 4.7±0.6 | 4.6±0.6 | 4.6±0.6 | 2.13 | 0.135 | 0.118 | |

| NASA- TLX | Mental demand | 22.8±23.7 | 19±25.5 | 25.3±28.7 | 0.50 | 0.580 | 0.030 |

| Physical demand | 4.3±16.9 | 0.2±0.4 | 0.2±0.4 | 1.00 | 0.379 | 0.059 | |

| Temporal Demand | 5.4±12.6 | 3.2±6.5 | 2.5±5.5 | 0.67 | 0.438 | 0.040 | |

| Satisfaction | 74.4±27.8 | 74.7±28.1 | 71.3±29.5 | 0.56 | 0.536 | 0.034 | |

| Effort | 6.9±16.9 | 17.5±24.3 | 15.4±22.8 | 3.98 | 0.033 | 0.199 | |

| Frustration | 0.8±2.4 | 2.0±5.2 | 4.2±8.1 | 2.21 | 0.150 | 0.121 | |

3.3. Experiment 2: Correlations

During the French card session, patients showed a strong significant correlation between time spent to complete the task and the relevant number of trials (R = 0.826, p < 0.001). Both these performance parameters were significantly correlated also with episodic memory (p < 0.05; R = -0.755, R = -0.524, respectively), number calculation (R = -0.638, R = -0.599), and sentence reading (R = -0.574, R = -0.653). Then, time to complete the task (but not number of trials) correlated with picture naming (R = -0.688), and number of trials (but not time) with recall and recognition (R = -0.518). Finally, the perceived effort measured by NASA-TLX correlated with the memory item of MMSE (R = -0.636, p = 0.006).

When artistic pictures were used instead of French cards, we did not found a significant, correlation between time and number of trials needed to complete the task (R = 0.450, p = 0.070). According to this result, time (but not trials) was found correlated with picture pointing (R = -0.511) and sentence reading (R = -0.665), whereas number of trials (but not time) with recall and recognition (R = -0.602) and memory item of MMSE (R = -0.604). The perceived effort was not correlated with any of the assessed parameters.

For photos of TV journalists, time and number of trials were significantly correlated (R = 0.792), and both these variables were correlated with number calculation (R = -0.495, R = -0.506, respectively). Number of trials was correlated also with recall and recognition (R = -0.483). The perceived effort was correlated with the second item of MMSE (R = -0.512).

4. Discussion

First of all, both healthy subjects and patients judged as highly usable the digital version of memory card. They also reported a low discomfort. These results were independent by the type of stimuli presented: French cards, photos of people or artistic portraits. Positive judgments were given also in terms of NASA-TLX scores. Interestingly, only patients showed a significant difference among the three sessions in the perceived effort.

The reduction of the perceived effort, accompanied by a better performance in presence of artistic stimuli was previously defined as Michelangelo effect [6], and used in rehabilitation protocols for subjects with stroke [8]. The results of the present study did not show a “Michelangelo effect” for healthy subjects. In fact, their performance and their perceived effort were not significantly different among the three conditions. Previous studies reported this effect also in healthy subjects during virtual paintings [6] and virtual sculpturing [16]. This difference could be explained by the fact that the digital memory game task proposed in this study was easier than the tasks tested in virtual reality. The easiness of this task may have implied a “ceiling effect” on the judgments of the perceived effort. This interpretation is based on a previous study showing that too simple memory tasks for healthy adults are often affected by ceiling effect [22]. In that study, this ceiling effect was less present in patients with cortical degenerative condition [22].

Similarly, also for the patients with stroke enrolled in our study, the memory task was not so simple and time needed to complete the task, as well as the number of trials, were obviously longer than those recorded for healthy subjects. Interestingly, these two parameters were significantly lower when patients turned artistic images than when they performed the same task with French cards. Furthermore, they reported a lower perceived effort in presence of artistic stimuli. These results are perfectly in line with the presence of a “Michelangelo effect” for patients with stroke [6].

Correlations with clinical parameters revealed interesting results. For both the sessions with French cards and with photos of famous people, the time and the number of trials needed to complete the task were significantly correlated each other, and the perceived effort was related to the patient’s memory assessed by the recall item of MMSE. These correlations were not statistically significant in presence of artistic stimuli. The absence of the correlation between time and trial could be related to a less systematic approach by patients in presence of paintings. As reported in the studies about the Michelangelo effect, in presence of artistic images the patients performed less kinematic errors [6]. Then, the perceived effort was not significantly correlated with patient’s memory, suggesting that the Michelangelo effect was generalized independently by the patient’s mnemonic capacity. On the other hand, this effect was observed for virtual paintings [6], virtual sculpturing [16] and now for memory card gaming, suggesting that it could be present in very different tasks.

About the assessed cognitive functions, we expected to find a significant correlation between the performance and the items related to memory.

The OCS-recall and recognition item resulted correlated with trials for all the three times of images, suggesting that it was the most important cognitive function involved into this task. Since this OCS-item is related to a verbal recall and recognition [20,23], although the task of the memory game was not verbal, it is possible that patients needed a verbalization in their mind.

The OCS-episodic memory item resulted correlated with time and trials only for cards. The score of the recall item of MMSE, related to episodic memory, was found correlated with the perceived effort assessed by NASA-TLX during the task performed with the cards and the photos, but not for paintings, for which the correlation of this item was with number of trials.

About the other cognitive functions, the score recorded for the number calculation item resulted correlated with time and trials for cards and photos, but not for paintings. It should be noted that number calculation is assessed by OCS with the purpose of checking for preserved mathematical basic abilities (such as the recognition of the number reported on the cards, or counting the remaining cards to turn) and not to detect higher level math deficits [20]. Significant correlation with OCS-item of picture naming was found for cards and photos, but not for paintings. The OCS-item related to language, and in particular sentence reading, was found correlated with time and trials for cards, and with time for paintings.

Finally, the OCS-item picture pointing was found correlated with the time needed to complete the task only for paintings. This item was classified as related to semantic cognitive function and hence to language domain in the original [20] and following versions [24,25,26] of OCS, although a recent study suggested to reclassify it as related to visuomotor control [21].

All these results seem to suggest the presence of the Michelangelo effect with artistic stimuli for patients with stroke, with an improvement of their performance and a reduction of their perceived effort when they interact with artistic stimuli. The recall of positions of paintings seemed to be associated to different cognitive functions with respect to the other two types of stimuli. In fact, despite for all the types of images the memory recall and recognition functions were important, the performance of patients in the sessions with cards and photos seemed to be related to the language and arithmetic domain. Language and numbers were two different domains of the original version of OCS [20], but a recent principal component analysis revealed that they could be classified as a single domain [21]. The importance of this domain seemed to be limited to artistic stimuli, for which the visuomotor control seemed to be crucial. This result could be interpreted as an involvement of linguistic and logical intelligence [27,28] for sessions with cards and photos, probably for the need to verbalize the name of cards (number and sign) or the name or description of famous people reported in pictures. Conversely, visual processing and hence visual and kinesthetic intelligence [27,28] could be more involved in artistic stimuli.

The different involvement of cognitive domains, together with the possible engagement elicited by artistic stimuli reported in previous studies [1,29,30] could be at the basis of the observed Michelangelo effect in patients with stroke during this memory task.

The results of this study should be carefully considered at the light of its limits. The first is the reduced sample size, especially for patients with stroke, also given the possible heterogeneity of the cognitive deficits of this population [31]. Another limit is that we have assessed a restricted part of the involved cognitive functions. For example, we did not assess the executive functions, that play a fundamental role in the rehabilitation of patients with stroke [32]. Finally, this study has a cross-over design, and a randomized controlled trial could be conducted to investigate the efficacy of cognitive neurorehabilitation designed to exploit the Michelangelo effect for artistic stimuli, as done for motor neurorehabilitation [8].

In conclusion, this study reports evidence for a Michelangelo effect with patients with stroke also with cognitive task, particularly memory task, in presence of artistic stimuli. As reported by the World Health Organization, art therapy may induce benefits through the modulation of neurotransmitters such as serotonin, the reductions in stress hormones such as cortisol and decreases in inflammatory immune responses, and contributing to enhancing emotional (e.g. self-expression, positive mood induction and diversion), and cognitive aspects (e.g. stimulation of memory) [1,33]. Finally, our results may provide a first insight about a possible cognitive interpretation of the Michelangelo effect in accordance with the efficacy of art-therapy protocols reported in literature for cognitive treatments [1,34,35].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.I., S.P., G.A.; methodology, C.S., C.C.; software development: C.C.; statistical analysis, M.I.; clinical assessment of patients and enrollment: D.D.A., P.C., V.V., A.S.; psychological assessment of patients: C.S.; experiments: C.S., C.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.I., and C.S.; writing—review and editing, S.P., G.A., F.M. and F.B.; supervision, S.P., G.A., F.M. and F.B.; project administration, M.I.; funding acquisition, M.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Sapienza University of Rome, grant number RM122181675BD4-FF, grant name: Project Michelangelo.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Independent Local Ethics Committee of Santa Lucia Foundation (CE/PROG.795, date of approval 2 December 2019) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymous data are available on request to send to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Authors would thank Camilla Vallebella, Tommaso D’Amico and Tommaso Mastropietro for their help in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fancourt, D.; Finn, S. What is the Evidence on the Role of the Arts in Improving Health and Well-Being? A Scoping Review; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019.

- Adolphs, R., Damasio, H., Tranel, D., Cooper, G., and Damasio, A. R. (2000). A role for somatosensory cortices in the visual recognition of emotion as revealed by three-dimensional lesion mapping. J. Neurosci. 20, 2683–2690.

- Di Dio, C., Ardizzi, M., Massaro, D., Di Cesare, G., Gilli, G., Marchetti, A., et al. (2016). Human, nature, dynamism: the effects of content and movement perception on brain activations during the aesthetic judgment of representational paintings. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 9:705. [CrossRef]

- Freedberg, D., and Gallese, V. (2007). Motion, emotion and empathy in esthetic experience. Trends Cogn. Sci. 11, 197–203.

- Raglio, A., Panigazzi, M., Colombo, R., Tramontano, M., Iosa, M., Mastrogiacomo, S., Baiardi, P., Molteni, D., Baldissarro, E., Imbriani, C., Imarisio, C., Eretti, L., Hamedani, M., Pistarini, C., Imbriani, M., Mancardi, G. L., Caltagirone, C. (2021). Hand rehabilitation with sonification techniques in the subacute stage of stroke. Scientific reports, 11(1), 7237.

- Iosa, M., Aydin, M., Candelise, C., Coda, N., Morone, G., Antonucci, G., Marinozzi, F., Bini, F., Paolucci, S., Tieri, G. (2021). The Michelangelo Effect: Art Improves the Performance in a Virtual Reality Task Developed for Upper Limb Neurorehabilitation. Frontiers in psychology, 11, 611956.

- Iosa, M., Bini, F., Marinozzi, F., Antonucci, G., Pascucci, S., Baghini, G., Guarino, V., Paolucci, S., Morone, G., Tieri, G. (2022). Inside the Michelangelo effect: The role of art and aesthetic attractiveness on perceived fatigue and hand kinematics in virtual painting. PsyCh journal, 11(5), 748–754.

- De Giorgi, R., Fortini, A., Aghilarre, F., Gentili, F., Morone, G., Antonucci, G., Vetrano, M., Tieri, G., Iosa, M. (2023). Virtual Art Therapy: Application of Michelangelo Effect to Neurorehabilitation of Patients with Stroke. Journal of clinical medicine, 12(7), 2590.

- Gibson, E., Koh, C. L., Eames, S., Bennett, S., Scott, A. M., Hoffmann, T. C. (2022). Occupational therapy for cognitive impairment in stroke patients. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews, 3(3), CD006430.

- Maggio, M. G., De Bartolo, D., Calabrò, R. S., Ciancarelli, I., Cerasa, A., Tonin, P., Di Iulio, F., Paolucci, S., Antonucci, G., Morone, G., Iosa, M. (2023). Computer-assisted cognitive rehabilitation in neurological patients: state-of-art and future perspectives. Frontiers in neurology, 14, 1255319.

- Zucchella, C., Capone, A., Codella, V., Vecchione, C., Buccino, G., Sandrini, G., Pierelli, F., Bartolo, M. (2014). Assessing and restoring cognitive functions early after stroke. Functional neurology, 29(4), 255–262.

- Prokopenko, S.V., Bezdenezhnykh, A.F., Mozheyko, E.Y. et al. (2019) Effectiveness of Computerized Cognitive Training in Patients with Poststroke Cognitive Impairments. Neurosci Behav Physi 49, 539–543.

- Silva da Cunha, S.N., Travassos Junior, X.L., Guizzo, R. et al. The digital memory game: an assistive technology resource evaluated by children with cerebral palsy. Psicol. Refl. Crít. 29, 5 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Lopatina, O. L., Komleva, Y. K., Gorina, Y. V., Higashida, H., Salmina, A. B. (2018). Neurobiological Aspects of Face Recognition: The Role of Oxytocin. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience, 12, 195.

- Massaro, D., Savazzi, F., Di Dio, C., Freedberg, D., Gallese, V., Gilli, G., Marchetti, A. (2012). When art moves the eyes: a behavioral and eye-tracking study. PloS one, 7(5), e37285.

- Pascucci, S., Forte, G., Angelini, E., Marinozzi, F., Bini, F., Antonucci, G., Iosa, M., & Tieri, G. (2024). Michelangelo Effect in Virtual Sculpturing: Prospective for Motor Neurorehabilitation in the Metaverse. Journal of cognition, 7(1), 17. [CrossRef]

- Vidal, E., Castro-Gutierrez, E., Arisaca, R., Paz-Valderrama, A., & Albiol-Pérez, S. (2023). Serious Game for Fine Motor Control Rehabilitation for Children With Epileptic Encephalopathy: Development and Usability Study. JMIR formative research, 7, e50492. [CrossRef]

- Rickenbacher-Frey, S., Adam, S., Exadaktylos, A. K., Müller, M., Sauter, T. C., & Birrenbach, T. (2023). Development and evaluation of a virtual reality training for emergency treatment of shortness of breath based on frameworks for serious games. GMS journal for medical education, 40(2), Doc16. [CrossRef]

- Vidal, E., Castro-Gutierrez, E., Arisaca, R., Paz-Valderrama, A., & Albiol-Pérez, S. (2023). Serious Game for Fine Motor Control Rehabilitation for Children With Epileptic Encephalopathy: Development and Usability Study. JMIR formative research, 7, e50492. [CrossRef]

- Demeyere, N., Riddoch, M. J., Slavkova, E. D., Bickerton, W. L., & Humphreys, G. W. (2015). The Oxford Cognitive Screen (OCS): validation of a stroke-specific short cognitive screening tool. Psychological assessment, 27(3), 883–894. [CrossRef]

- Iosa, M., Demeyere, N., Abbruzzese, L., Zoccolotti, P., & Mancuso, M. (2022). Principal Component Analysis of Oxford Cognitive Screen in Patients With Stroke. Frontiers in neurology, 13, 779679. [CrossRef]

- Clegg, F., & Warrington, E. K. (1994). Four easy memory tests for older adults. Memory (Hove, England), 2(2), 167–182. [CrossRef]

- Demeyere, N., Riddoch, M. J., Slavkova, E. D., Jones, K., Reckless, I., Mathieson, P., & Humphreys, G. W. (2016). Domain-specific versus generalized cognitive screening in acute stroke. Journal of neurology, 263(2), 306–315. [CrossRef]

- Shendyapina, M., Kuzmina, E., Kazymaev, S., Petrova, A., Demeyere, N., & Weekes, B. S. (2019). The Russian version of the Oxford Cognitive Screen: Validation study on stroke survivors. Neuropsychology, 33(1), 77–92. [CrossRef]

- Robotham, R. J., Riis, J. O., & Demeyere, N. (2020). A Danish version of the Oxford cognitive screen: a stroke-specific screening test as an alternative to the MoCA. Neuropsychology, development, and cognition. Section B, Aging, neuropsychology and cognition, 27(1), 52–65. [CrossRef]

- Huygelier, H., Schraepen, B., Demeyere, N., & Gillebert, C. R. (2020). The Dutch version of the Oxford Cognitive Screen (OCS-NL): normative data and their association with age and socio-economic status. Neuropsychology, development, and cognition. Section B, Aging, neuropsychology and cognition, 27(5), 765–786. [CrossRef]

- Gardner, H. (1993). Multiple intelligences: The theory in practice. New York: Basic Books.

- Gardner, H. (2017). Taking a multiple intelligences (MI) perspective. Behav. Brain Sci. 40:e203. [CrossRef]

- Morris, J. H., Kelly, C., Toma, M., Kroll, T., Joice, S., Mead, G., Donnan, P., & Williams, B. (2014). Feasibility study of the effects of art as a creative engagement intervention during stroke rehabilitation on improvement of psychosocial outcomes: study protocol for a single blind randomized controlled trial: the ACES study. Trials, 15, 380. [CrossRef]

- Sit, J. W. H., Chan, A. W. H., So, W. K. W., Chan, C. W. H., Chan, A. W. K., Chan, H. Y. L., Fung, O. W. M., & Wong, E. M. L. (2017). Promoting Holistic Well-Being in Chronic Stroke Patients Through Leisure Art-Based Creative Engagement. Rehabilitation nursing: the official journal of the Association of Rehabilitation Nurses, 42(2), 58–66. [CrossRef]

- Jaywant, A., & Keenan, A. (2024). Pathophysiology, Assessment, and Management of Post-Stroke Cognitive Impairment, Depression, and Fatigue. Physical medicine and rehabilitation clinics of North America, 35(2), 463–478. [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, M., Iosa, M., Abbruzzese, L., Matano, A., Coccia, M., Baudo, S., Benedetti, A., Gambarelli, C., Spaccavento, S., Ambiveri, G., Megna, M., Tognetti, P., Maietti, A., Rinaldesi, M. L., Gamberini, G., Varalta, V., Morone, G., Ciancarelli, I., & CogniReMo Study Group (2023). The impact of cognitive function deficits and their recovery on functional outcome in subjects affected by ischemic subacute stroke: results from the Italian multicenter longitudinal study CogniReMo. European journal of physical and rehabilitation medicine, 59(3), 284–293. [CrossRef]

- Van Lith, T., Schofield, M. J., & Fenner, P. (2013). Identifying the evidence-base for art-based practices and their potential benefit for mental health recovery: a critical review. Disability and rehabilitation, 35(16), 1309–1323. [CrossRef]

- Kongkasuwan, R., Voraakhom, K., Pisolayabutra, P., Maneechai, P., Boonin, J., & Kuptniratsaikul, V. (2016). Creative art therapy to enhance rehabilitation for stroke patients: a randomized controlled trial. Clinical rehabilitation, 30(10), 1016–1023. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S., Huang, X., Liu, Y., Yue, J., Li, Y., & Chen, L. (2024). A scoping review of the use of creative activities in stroke rehabilitation. Clinical rehabilitation, 38(4), 497–509. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Examples of the digital memory game. On the left, the version with French cards with a couple correctly found, and all the other cards faced down. On the right, the version with paintings, all of them turned over.

Figure 1.

Examples of the digital memory game. On the left, the version with French cards with a couple correctly found, and all the other cards faced down. On the right, the version with paintings, all of them turned over.

Figure 2.

Mean (columns) and standard deviation (bars) of the Time (in seconds, on the left) and the number of trials (on the right) spent to complete the task in the three sessions by healthy subjects: paintings (orange columns), photos (blue columns) and cards (green columns).

Figure 2.

Mean (columns) and standard deviation (bars) of the Time (in seconds, on the left) and the number of trials (on the right) spent to complete the task in the three sessions by healthy subjects: paintings (orange columns), photos (blue columns) and cards (green columns).

Figure 3.

Mean (columns) and standard deviation (bars) of the Time (in seconds, on the left) and the number of trials (on the right) spent to complete the task in the three sessions by patients with stroke: paintings (orange columns), photos (blue columns) and cards (green columns). Stars highlighted the statistically significant differences found by post-hoc tests.

Figure 3.

Mean (columns) and standard deviation (bars) of the Time (in seconds, on the left) and the number of trials (on the right) spent to complete the task in the three sessions by patients with stroke: paintings (orange columns), photos (blue columns) and cards (green columns). Stars highlighted the statistically significant differences found by post-hoc tests.

Table 1.

Mean ± standard deviation of the items of USEQ and of NASA-TLX for healthy subjects, with F-values (and relevant degrees of freedom), p-values and partial eta squared (η p 2) as results of the RM-Anova.

Table 1.

Mean ± standard deviation of the items of USEQ and of NASA-TLX for healthy subjects, with F-values (and relevant degrees of freedom), p-values and partial eta squared (η p 2) as results of the RM-Anova.

| Healthy Subjects | Paintings | Photos | Cards | F(2,14) | p-value | η p 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USEQ | Experienced enjoyment | 4.4±1.1 | 4.1±0.9 | 4.2±0.7 | 1.20 | 0.315 | 0.079 | |

| Successful use | 4.9±0.3 | 4.7±0.6 | 4.7±0.6 | 1.00 | 0.370 | 0.067 | ||

| Ability to control | 4.6±0.7 | 4.8±0.6 | 4.6±0.7 | 1.31 | 0.282 | 0.086 | ||

| Clarity of information | 4.9±0.3 | 4.9±0.4 | 4.7±0.8 | 0.68 | 0.440 | 0.047 | ||

| Discomfort | 1.3±0.8 | 1.3±0.8 | 1.2±0.8 | 1.00 | 0.381 | 0.067 | ||

| Perceived utility | 4.3±1.2 | 4.3±1.1 | 4.4±1.1 | 0.16 | 0.839 | 0.011 | ||

| NASA-TLX | Mental demand | 42.0±20.6 | 40.3±22.2 | 38.3±25.0 | 0.46 | 0.621 | 0.032 | |

| Physical demand | 13.5±17.7 | 15.6±20.0 | 9.9±10.5 | 1.39 | 0.263 | 0.090 | ||

| Temporal Demand | 20.1±19.2 | 27.2±23.0 | 15.3±14.8 | 2.11 | 0.148 | 0.131 | ||

| Satisfaction | 64.4±22.6 | 65.1±21.0 | 62.0±20.5 | 0.22 | 0.801 | 0.016 | ||

| Effort | 40.0±26.5 | 35.5±21.6 | 41.2±22.8 | 0.55 | 0.558 | 0.038 | ||

| Frustration | 8.3±9.5 | 8.9±10.3 | 8.5±9.7 | 0.10 | 0.853 | 0.007 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Copyright: This open access article is published under a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license, which permit the free download, distribution, and reuse, provided that the author and preprint are cited in any reuse.

Michelangelo Effect in Cognitive Rehabilitation: Using Art in a Digital Visuospatial Memory Task

Claudia Salera

et al.

,

2024

Rapid Prototyping of Virtual Reality Cognitive Exercises in a Tele–Rehabilitation Context

Damiano Perri

et al.

,

2020

Deploying Serious Games for Cognitive Rehabilitation

Damiano Perri

et al.

,

2022

MDPI Initiatives

Important Links

© 2024 MDPI (Basel, Switzerland) unless otherwise stated