Preprint

Article

Distinctive Deposition Patterns of Sporadic Transthyretin-Derived Amyloidosis in the Atria: A Forensic Autopsy–Based Study

Altmetrics

Downloads

129

Views

44

Comments

0

A peer-reviewed article of this preprint also exists.

supplementary.docx (43.35KB )

This version is not peer-reviewed

Submitted:

05 July 2024

Posted:

12 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Alerts

Abstract

Left-to-right differences in the histopathologic patterns of transthyretin-derived amyloid (ATTR) deposition in the atria of older adults have not yet been investigated. Hence, this study evaluated heart specimens from 325 serial autopsy subjects. The amount of ATTR deposits in the seven cardiac regions, including both sides of atria and atrial appendages, was evaluated semiquantitatively. Using digital pathology, we quantitatively evaluated the immunohistochemical deposition burden of ATTR in the myocardium. We identified 20 sporadic ATTR cardiac amyloidosis cases (9 males). All patients had ATTR deposition in the left atrial regions of the myocardium. In the semiquantitative analysis, 14 of the 20 cases showed more severe ATTR deposition on the left atrial regions than on the right side, with statistically significant differences in the pathology grading (p < 0.01 for both the atrium and atrial appendage). Quantitative analysis further supported the difference. Moreover, six had ATTR deposition in the epineurium and/or neural fibres of the atria. Cluster analysis revealed that ATTR deposition in the myocardium was significantly more severe in males than in females. The heterogeneous distribution of amyloid deposits between atria revealed in this study may impair the orderly transmission of the cardiac conduction system and induce arrhythmias, which may be further aggravated by additional neuropathy in the advanced phase. This impairment could be more severe among males. These findings emphasise that atrial evaluation is important for individuals with sporadic ATTR cardiac amyloidosis, particularly for early detection.

Keywords:

Subject: Medicine and Pharmacology - Pathology and Pathobiology

1. Introduction

Amyloidosis is classified according to the precursors of amyloid fibril proteins deposited in tissues [1]. Although various symptoms can arise from amyloid deposition, cardiac amyloidosis (CA) is the primary cause of death among patients with systemic amyloidosis [2]. CA primarily results from two forms of precursor proteins: transthyretin-derived amyloid (ATTR) and immunoglobulin light chain-derived amyloid [3]. Recently, the importance of diagnosing ATTR-CA has been exponentially recognised because of advances in diagnostic and therapeutic methods [4,5]. Especially, early diagnosis is necessary, given that the therapeutic outcome of drugs that stabilise transthyretin is more effective when treatment is administered early [6,7]. Therefore, the histopathological progression pattern in patients with ATTR-CA should be comprehensively understood to establish more effective diagnostic approaches.

In recent years, the evaluation of ATTR deposition in the atria has been given increased attention [8,9,10,11]. We previously found that ATTR deposition patterns within the atrial septum (AS) differed on each side [12]. Consequently, the distribution and severity of ATTR deposition may differ between the left and right atrial regions, including the atrium and atrial appendage. Although atrial natriuretic factor–derived amyloid (AANF) is commonly found in the atria of nearly all old-aged patients with a left-predominant deposition [13,14,15], the deposition pattern of ATTR in the left and right atrial regions remain uninvestigated. Furthermore, several studies have reported the potential colocalisation of ATTR and AANF [8,11,12,16]. However, the relationship between ATTR and AANF is yet to be elucidated.

We previously reported that patients with sporadic ATTR-CA (sATTR-CA) could be at risk for sudden cardiac death (SCD), even from an early phase [12]. Thus, apart from the severity of ATTR deposition in the myocardium, additional risk factors for SCD might be involved. ATTR deposition reportedly leads to cardiac sympathetic denervation [17,18], and sympathetic denervation could be a contributing factor to SCD in patients with Parkinson’s disease [19]. However, currently, no studies have explored this aspect.

Therefore, this study examined a series of cases of sATTR-CA identified through histopathological analysis in our laboratory. We aimed to assess whether the deposition pattern of sATTR differs between the right atrium (RA) and left atrium (LA), to evaluate the relationship between ATTR and AANF deposits and to investigate whether ATTR can accumulate in the peripheral nerves of the atria.

2. Results

2.1. Clinical Profiles and Demographics

Out of 325 cases, 20 (6.2%) were sATTR amyloidosis (18.1% in individuals aged ≥80 years [17/94 cases]). Table 1 summarises the clinical information of these patients.

Of these 20 cases, 9 were males and 11 were females (mean age: 85.6 ± 4.8 years [78–94 years] and 85.5 ± 6.0 years [79–97 years], respectively). Regarding the cause of death, 3 died from illness (with 1 related to ATTR-CA), 5 by suicide and 12 from accidental causes. Clinical history data from 19 patients revealed that 15 (79%), 5 (26%) and 3 (16%) had hypertension, hyperlipidemia and diabetes, respectively. Furthermore, 8 out of the 20 patients had a measured heart weight-to-estimated normal heart weight ratio exceeding 1.5 [26]. None of the cases had a family history of amyloidosis or had been diagnosed with ATTR-CA before death. Additionally, only 1 patient was clinically diagnosed with atrial fibrillation, 4 had coronary artery stenosis (≥75% reduction in the luminal cross-sectional area), but none had chronic heart failure prior to death.

2.2. Histopathological Findings of ATTR and AANF in the Heart

Table 2 summarises the positive deposition rates of ATTR and AANF in each anatomical area.

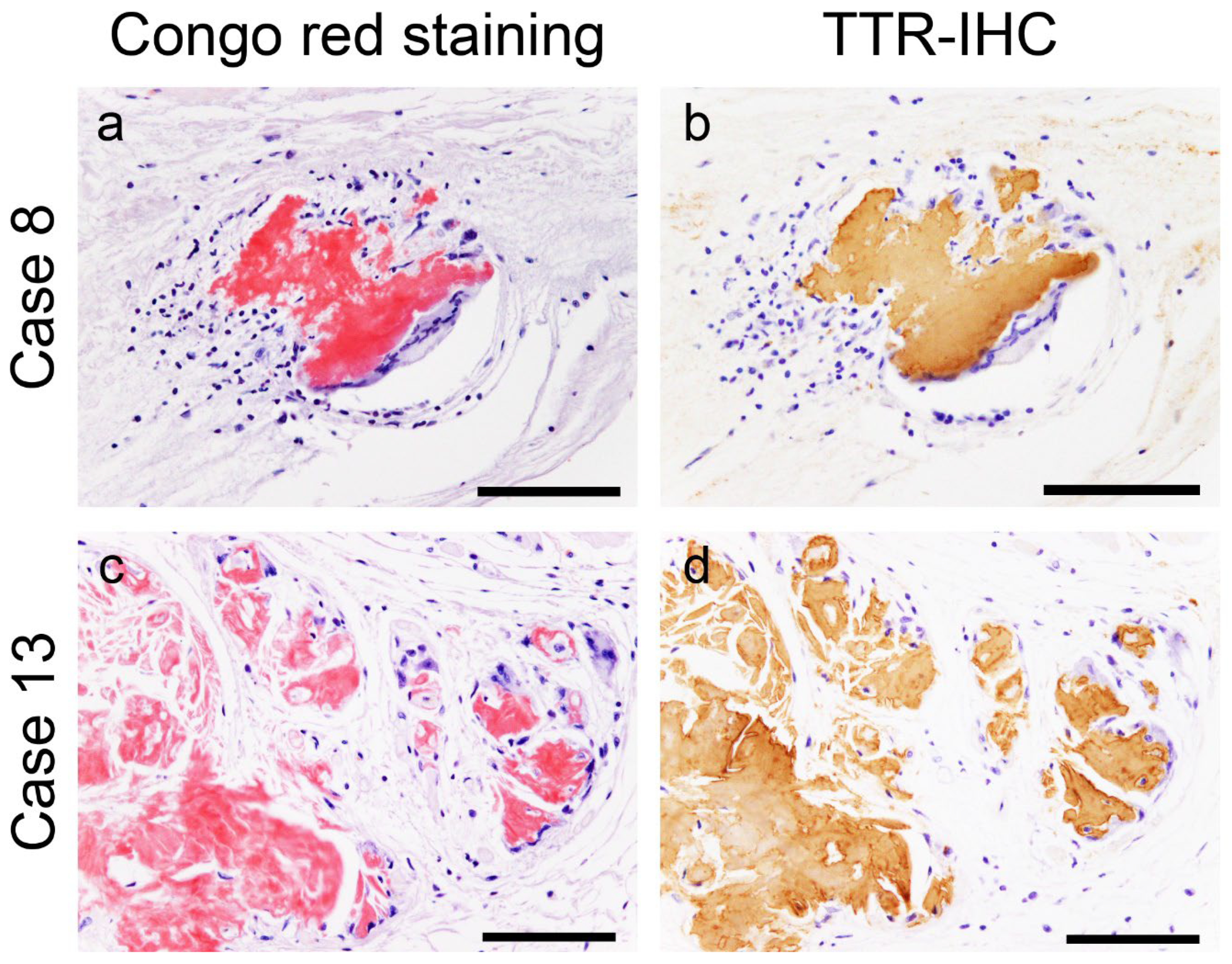

All patients had ATTR deposition in the myocardial layer in the LA and left atrial appendage (LAA), and these areas had a significantly higher deposition frequency than the RA and right atrial appendage (RAA) (p = 0.02 and p < 0.01, respectively). Interestingly, one patient showed only vascular deposition in the ventricular septum (VS). Furthermore, ATTR deposition in the endocardial interstitium was significantly more frequent on the right side of the AS than on the left side (p < 0.01). Only three patients had ATTR deposition in the sinoatrial nide (SAN), and none in the atrioventricular node (AVN). Neural/perineural involvement was observed in six patients, with two exhibiting both neural and perineural involvement. However, in most cases, the atrial peripheral nerve fibres were free of ATTR deposition. Additionally, we incidentally found multinucleated giant cells infiltrating around ATTR deposits in two patients (patients 8 and 13; Figure 1).

The frequency of AANF deposition did not significantly differ between the LA and RA regions.

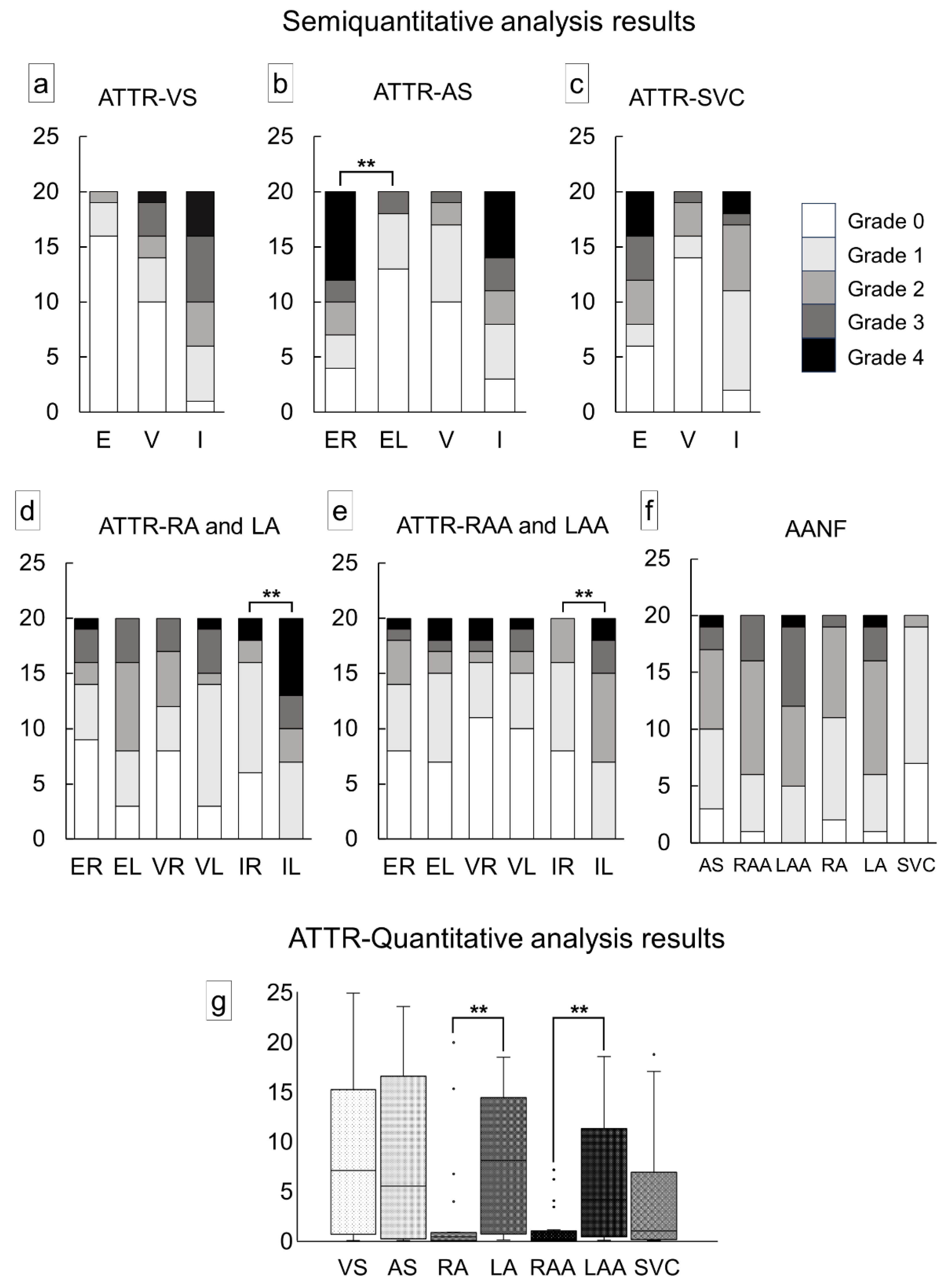

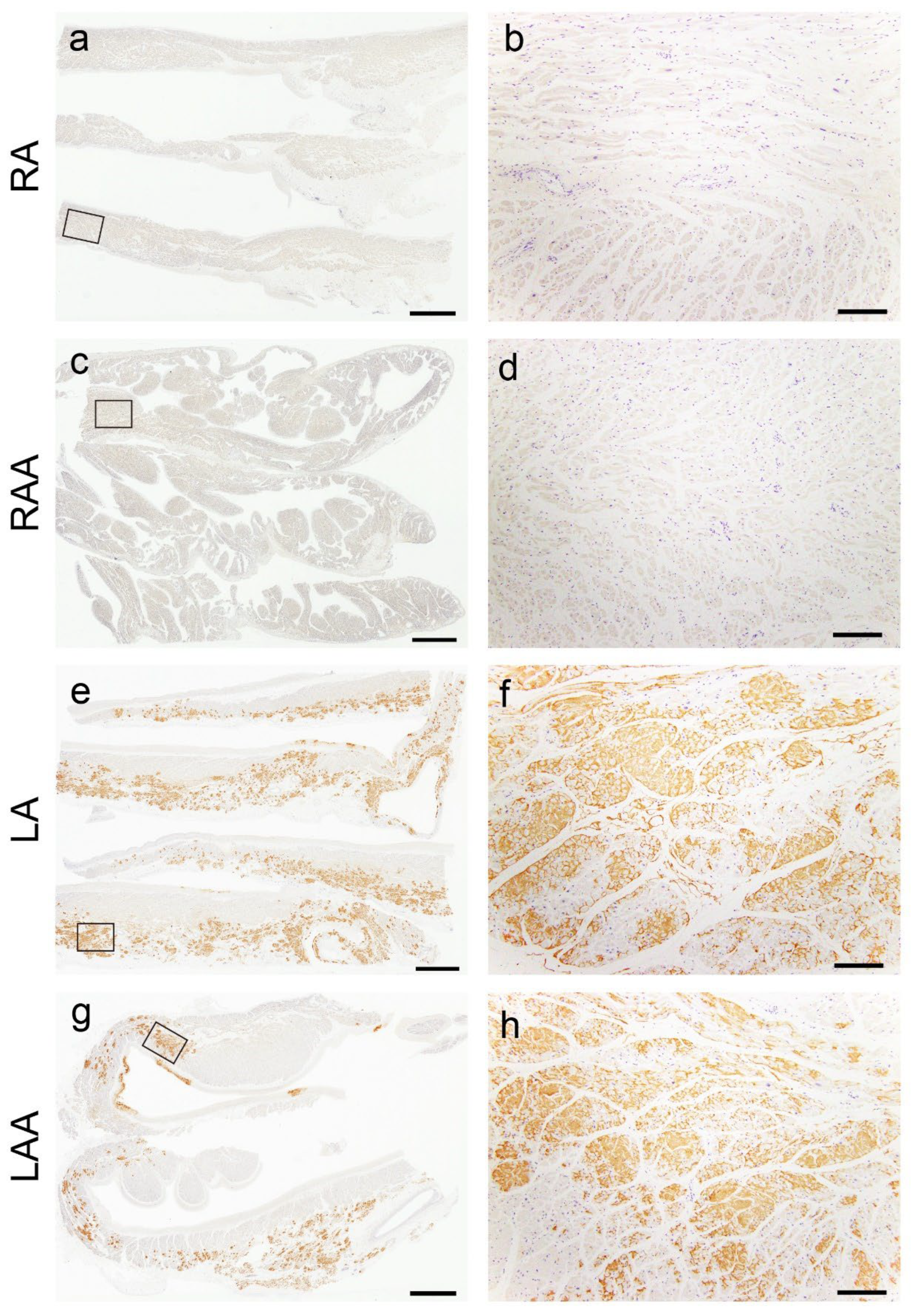

Figure 2 illustrates the semiquantitative and quantitative pathological evaluation results (all analysis results are provided in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2, with a summary in Supplementary Table S3), and Figure 3 shows representative pathological microphotographs of ATTR deposition in both sides of the atrial regions.

In the VS, ATTR deposition in the myocardial interstitium was severe, whereas that in the endocardial interstitium was mild (Figure 2a). Conversely, in the AS, deposition was observed in both the myocardial and endocardial interstitium in many cases, with the latter being significantly more severe on the right side (Figure 2b). ATTR deposition severity in the superior vena cava (SVC) was similar to that in the AS (Figure 2c). In the semiquantitative analysis, 14 out of 20 cases showed significantly more severe ATTR deposition on the LA regions than on the RA regions (Figure 2d,e). Our quantitative analysis further supported the left-side predominant ATTR deposition in the myocardium (Figure 2g). Meanwhile, although AANF deposition was generally more severe on the LA regions than the RA regions, difference was not statistically significant (Figure 2f). Hence, this left-side predominant deposition pattern was considered characteristic of ATTR (Figure 3).

2.3. Evaluation of the Colocalisation of ATTR and AANF Using Single and Double IHC

Figure 4 provides representative microphotographs for this evaluation.

In the single immunohistochemistry (IHC), some amyloid nodules consisted of both ATTR and AANF deposits; however, the positive areas of ATTR and AANF were observed separately, with no clear colocalisation (Figure 4a–d). Thus, to elucidate whether ATTR and AANF are colocalised, we conducted double IHC on patients who showed severe ATTR deposition (grade 4) in the LA on the semiquantitative analysis. However, specimens stained with double IHC showed no clear colocalisation of ATTR and AANF (Figure 4e,f).

2.4. Subgroups Classified by Cluster Analysis

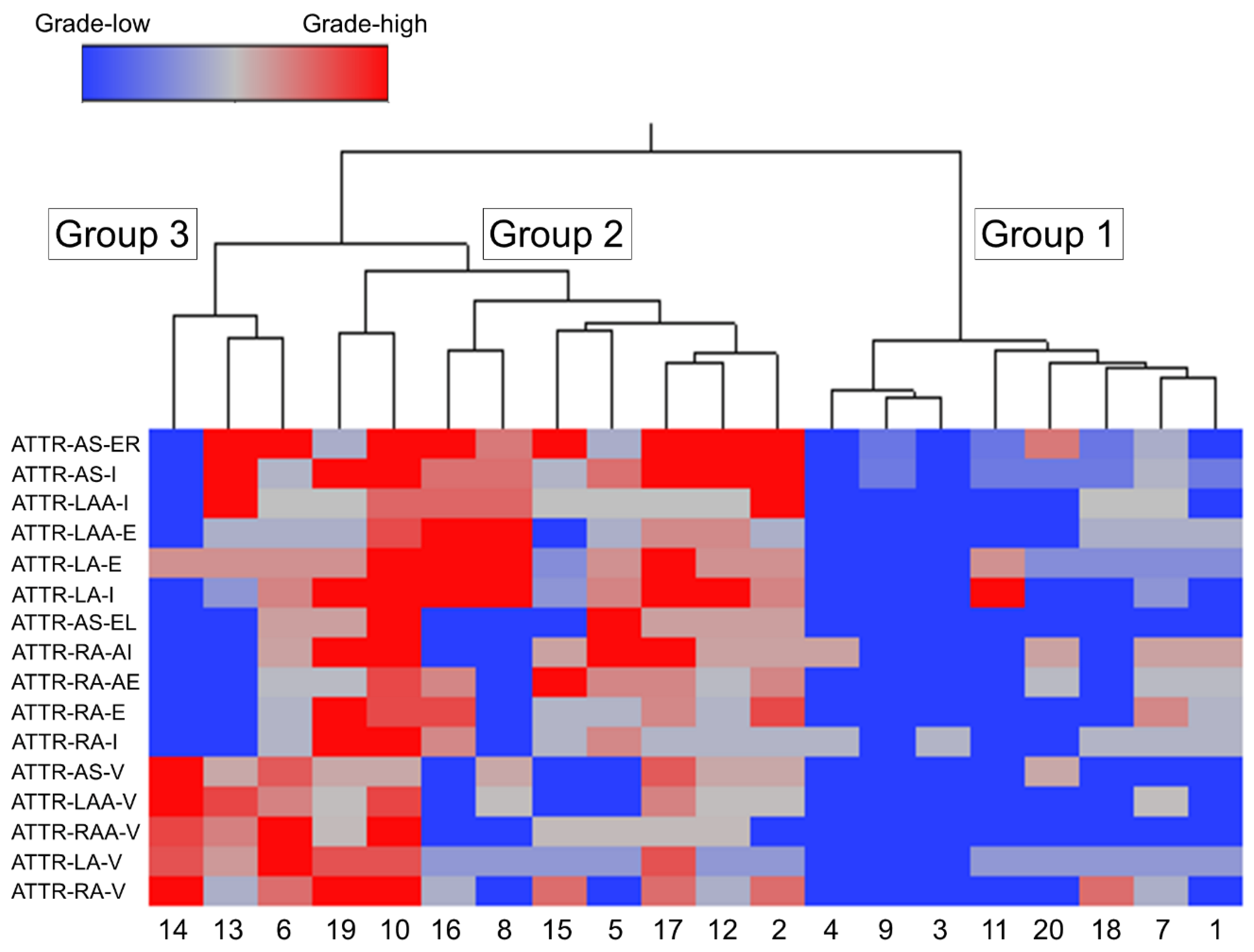

We used cluster analysis to classify all cases into three groups according to the severity of ATTR deposition in the AS, RA, LA, RAA and LAA (Figure 5).

Table 3 lists the clinicopathological features of each group.

Among the three groups, Group 1 (eight cases) had the mildest ATTR deposition severity, thereby considered as the ‘mild ATTR deposition group’. Interestingly, seven of the eight cases in this group were female; this number was significantly higher than that in Group 2.

Group 2 (nine cases) showed the most severe interstitial ATTR deposition, thereby regarded as the‘severe interstitial ATTR deposition group’. In contrast to Group 1, seven out of nine cases were male; thus, ATTR deposition in the myocardium may be more severe in males.

In Group 3 (three cases), the severity of ATTR deposition in the interstitium was not significantly different from Group 1, but it had the most severe vascular deposition. Thus, Group 3 was considered as the ‘vessel-predominant ATTR deposition group’.

Compared with ATTR deposition, AANF deposition severity did not significantly differ among the three groups.

2.5. Comparison of ATTR and AANF Deposition Severity between Males and Females

Table 4 summarises the results of the semiquantitative and quantitative analyses for females and males.

As shown by the cluster analysis, males were more severely affected than females in almost all measures of ATTR deposition, with statistically significant differences observed in the semiquantitative analysis of the VS interstitium and the quantitative analysis of the LA interstitium. Regarding AANF deposition severity, we noted no differences between the sexes.

3. Discussion

This study showed that sATTR-CA predominantly involves the LA regions. LA function evaluation has been widely reported to be useful for discriminating CA from other diseases with LV hypertrophy and predicting prognosis in patients with CA [11,21,22,23,24]. Thus, our study results provide histopathological support for these clinical observations. To our knowledge, this research is the first autopsy–based study demonstrating the left-predominant ATTR deposition patterns in the atria. Additionally, two patients (patients 10 and 19) exhibiting severe ATTR deposition in the RA also had severe ATTR deposition in the VS and LA; hence, RA involvement may be the most advanced phase in sATTR-CA. Consistent with this finding, Singulane et al. reported that abnormalities in RA size and strain are associated with a worse prognosis in patients with CA [9]. By comparing the amount of deposition in the LA and RA regions, ATTR-CA may be early detected. Differences in ATTR-CA in both atria are currently unreported and require further investigation.

Our previous study using the proximity ligation assay demonstrated the colocalisation of ANF and TTR in amyloid deposits in the AS [12]. Furthermore, Bandera et al. found ANF in the atrial ATTR deposits in three of five patients through a proteomic analysis [11]. In addition, AANF deposition is reportedly more severe in the LA than in the RA regions [13,14,15]. Taken together, the varying severity of ATTR deposition in the left and right sides of the AS and atria might be explained by the presence of synergistic effects between AANF and ATTR; however, we could not demonstrate this hypothesis through IHC methods. Regarding AANF, immunoreactivity tended to weaken as congophilia became stronger, making the evaluation through IHC difficult. This limitation is probably caused by the fact that the epitope recognised by the antibody used in this study was hidden as amyloid fibril formation progressed [25]; the same phenomenon may have prevented the detection of AANF deposits when combined with ATTR deposits. In histopathology specimens, proving whether AANF is codeposited with ATTR or whether non–amyloid-forming ANF is merely present in the ATTR deposits is difficult. Verifying the existence of cross-seeding is also nearly impossible. Thus, drawing conclusions from morphological studies alone is challenging, and in vitro investigations to evaluate cross-seeding activity are necessary to clarify the relationship between the two [26].

In addition to the presence of a synergetic interaction between ATTR and AANF, we have three other hypotheses for the cause of the left-side predominant ATTR deposition pattern in the atria. The first hypothesis is mechanical stimulation. Repetitive mechanical stimulus could favour ATTR fibrogenesis and/or tissue infiltration [27,28]. Given that the mean pressure is higher in the LA than in the RA, the former might have stronger mechanical stress than the latter, resulting in left-predominant ATTR deposition. Second, RA has resistance to ATTR deposition. As shown in our study, ATTR deposition is less likely to occur in conduction system tissues [12]. Therefore, ATTR deposition is less likely to occur in the RA, where the cardiac conduction system is concentrated, than in the LA, where it is absent. Third, a mechanism that can remove ATTR deposition exists. Some amyloid deposits cause granulomatous inflammation with multinucleated cells, probably as a result of an immune response to them [29,30]. Regarding ATTR deposits, we have recently reported that granulomas associated with sarcoidosis break ATTR deposits, indicating that this inflammation type is necessary for amyloid removal [31]. Moreover, Fontana et al. have reported three cases of antibody-induced reversal of ATTR amyloidosis–related cardiomyopathy, one of which underwent myocardial biopsy and showed multinucleated giant cell infiltration around ATTR deposits [32]. The present study found two cases exhibiting similar findings. In these cases, the RA region had no interstitial ATTR deposition, whereas the LA region had grade 2 or higher interstitial ATTR deposition, suggesting that the right side is more capable of removing deposits. This resistance to amyloid deposition in the RA system may also be associated with the left-predominant AANF deposition [13,14,15]. These hypotheses, if proven, could contribute to the development of not only therapeutic but also preventive strategies against ATTR-CA and should be explored in the future.

Our cluster analysis revealed that the burden of ATTR deposition in the myocardium, especially in the VS and LA, is significantly more severe in males than in females. As previously reported, sex differences appear to be closely related to ATTR-CA severity [12,33,34,35]. Sex hormone involvement has been suggested as one of the causes of this difference [33,36]. Interestingly, an association with sex hormones has also been noted for amyloid-beta [37,38], one of the common age-related amyloid deposits in older adults [39]. Thus, the role of sex hormones in the pathogenesis of age-related amyloidosis should be given more attention.

Sensory neuropathy reportedly occurs in 28.4% of patients with wild-type ATTR amyloidosis, suggesting that it can cause peripheral nervous system damage [40,41]. Consistent with this finding, our study showed that sATTR amyloidosis can extend into the epineurium and nerve fibres of peripheral nerves of the heart. To our knowledge, this study is the first to histopathologically demonstrate that ATTR deposition can extend to atrial peripheral nerves, suggesting that it can be one of the causes of SCD in sATTR-CA cases. However, epineurium/neural involvement was found only in cases showing grade 3 or higher myocardial interstitial infiltration and only to a very mild degree. In line with this finding, Gimelli et al. reported that in patients with wild-type ATTR, cardiac sympathetic denervation tended to worsen in parallel with the amyloid burden, although their correlation did not achieve statistical significance [17]. Taken together, myocardial denervation in sATTR-CA may not occur until at an advanced stage, and it could be milder than that in hereditary ATTR amyloidosis [18]. The significance of peripheral neuropathy in sATTR amyloidosis, including wild-type ATTR amyloidosis, needs further investigation.

In addition to a certain level of bias in our study population, this study was limited by clinical information, including the presence or absence of carpal tunnel syndrome or spinal stenosis, in some patients, mainly because of the lack of severe clinical symptoms or low cardiologist consultation rates. Moreover, we could not test TTR gene and exclude cases of geriatric onset of hereditary ATTR amyloidosis [42]. Thus, we described the cases as ‘sporadic ATTR’ instead of ‘wild-type ATTR’.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated a left-dominant deposition pattern of ATTR in the atrial regions. Together with the presence of a group of cases showing atrial predominance of deposition [12], ATTR deposition might occur irregularly in the heart between both atria and between atria and ventricles. Regarding AANF deposition, it might occur in the atria separately from ATTR deposition, accentuating the irregularity of atrial amyloid deposition. Thus, these deposits could induce arrhythmias by irregularly disrupting the stimulatory conduction system within the atria and from the atria to the ventricles. Moreover, this disruption might be further aggravated in the advanced stages by cardiac innervation impairment. These findings underscore the importance of atrial evaluation in sATTR-CA cases to early detect and differentiate from other conditions that cause cardiac hypertrophy.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Subjects

In our department, we retrospectively examined autopsy records documented from July 2019 to July 2021, during which samples from the LA, RA, LAA and RAA were routinely collected. Using these records, we evaluated heart specimens from 325 serial autopsy subjects in whom all organs, including the brain, could be sampled. Patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics (including the cause of death) were retrieved from the medical records of police examinations and contributions from family members or from the primary physician if a record indicated clinic visits. This study obtained approval from the Ethical Committee of Toyama University (I2020006) and conformed to the ethical standards outlined in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its 2008 amendment.

4.2. Tissue Samples

We sampled one block (containing 2–4 pieces of tissue) from each atrium and atrial appendage. The amount of amyloid deposition was evaluated in both atrial regions, AS, basilar VS at the AVN level and SVC at the SAN level. Specimens were fixed in 20% buffered formalin and routinely embedded in paraffin. Then, they were sectioned at 4 μm thick, followed by hematoxylin and eosin staining, elastica–Masson staining or IHC. We also prepared 6 μm-thick sections for phenol Congo red (pCR) staining [43].

4.3. Semiquantitative Grading System for ATTR and AANF Deposition

CA was screened according to a previously described method in our department [12]. Following confirmation of ATTR and AANF deposition by pCR staining and IHC, the severity of ATTR and AANF deposition in the myocardial interstitium, vessels and endocardial interstitium was assessed semiquantitatively. For this evaluation, we used a 5-point scoring system, taking into account the deposition patterns described in the existing literature [3,13,44] as follows:

ATTR interstitial grading:

Grade 0: None.

Grade 1: Focal and mild deposition in the perimyocyte area, without nodular lesions.

Grade 2: Multifocal deposition in the perimyocyte area, with minimal nodular lesions replacing the normal tissue.

Grade 3: Multifocal deposition, with some nodular lesions.

Grade 4: Diffuse deposition, with some nodular lesions.

ATTR vascular grading:

Grade 0: None.

Grade 1: Focal deposition.

Grade 2: Multifocal deposition with minimal involvement of the full thickness of the wall.

Grade 3: Multifocal deposition, with some occupying the full thickness of the wall.

Grade 4: Multifocal deposition, exhibiting an obstructive change (≥75% reduction in the luminal cross-sectional area).

ATTR endocardium grading:

Grade 0: None.

Grade 1: Focal and mild deposition in the subendocardial fibrous tissue.

Grade 2: Multifocal deposition with minimal massive deposits.

Grade 3: Multifocal deposition with some massive deposits.

Grade 4: Multifocal deposition with several massive deposits, with some occupying the full thickness of the endocardial fibrous tissue.

AANF deposition grading:

Grade 0: None.

Grade 1: Focal and mild deposition in the interstitium and/or vessels.

Grade 2: Multifocal deposition in the interstitium and vessels, with some surrounding the entire cardiomyocyte circumference.

Grade 3: Diffuse deposition surrounding the entire cardiomyocyte circumference.

Grade 4: Diffuse deposition with some nodular deposits.

Figure 6 shows representative microphotographs illustrating the deposition patterns of this grading system, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9 provide representative microphotographs of AANF deposition in the atrium and AS.

ANF immunoreactivity was detected not only in AANF deposits but also in the cytoplasm of cardiomyocytes, vessels and endocardium, sometimes exhibiting a disparity with pCR staining intensity (Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9). Consequently, the assessment of AANF deposition severity focused solely on the deposition pattern around cardiomyocytes in pCR-stained specimens, utilising AANF IHC to exclude ATTR deposition. All histopathological gradings were determined at the site with the most amyloid deposits observed under 100× magnification. Additionally, we assessed whether AVN, SAN, neural and perineural (epineurium) involvement existed in the atrial peripheral nerves.

4.4. Quantitative Analysis of ATTR Deposition Burden

We quantitatively assessed the amount of ATTR deposition burden in the myocardium in the VS, AS, both atria and atrial appendages, by using Image J/Fiji (version 1.54f) [45] as previously described [46,47]. Using a bright field microscope under 100× magnification (area per image: 1.68 × 1.32 mm), we photographed one location with the most severe ATTR deposition and then calculated the ATTR burden value. The microphotographs were acquired using a BX51 microscope (Olympus) equipped with a DP27 microscope camera and CellSens Standard imaging software (version 3.1, Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). All microphotographs were separately imported to Photoshop (Adobe Inc., CA, USA) and preprocessed by adjusting the contrast to clearly recognise small deposits and reduce the background noise of nonspecific immunoreactivity [48]. To improve measurement accuracy, we only assessed regions of 100 pixels or larger in area, considering the tendency to erroneously recognise lipofuscin in myocytes in patients with low ATTR deposition. In the quantitative analysis, cases of negative deposition in the myocardial interstitium in the semiquantitative analysis were counted as 0.

4.5. Single and Double IHC

Single IHC was performed using primary antibodies against prealbumin (transthyretin) (rabbit, clone EPR3219, 1:2000, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and ANF (mouse, clone 23/1, 1:20000; GeneTex, Irvine, CA). Antigens were retrieved using 98% formic acid for 1 min. In this IHC, we used the Leica Bond-MAX automation system and Leica Refine detection kits (Leica Biosystems, IL, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All sections were counterstained with hematoxylin.

In double IHC, the same antibodies mentioned above were used to assess whether ATTR and AANF were colocalised. First, IHC for AANF was conducted using the same procedure as that for single IHC. After the initial IHC, sections were incubated with 0.3% H2O2 for 10 min, followed by primary antibodies against transthyretin (overnight at 4 °C). Signal development was achieved using the immunoenzyme polymer method (Histofine Simple Stain MAX PO Multi; Nichirei Biosciences, Tokyo, Japan) with the Vina Green Chromogen Kit (BioCore Medical Technologies, MD, USA) for 5 min. We counterstained all sections with hematoxylin.

4.6. Statistical Analysis

Data were analysed using IBM SPSS statistics version 29 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), with the threshold for statistical significance set at p < 0.05. Ward’s hierarchical cluster analysis was conducted according to the semiquantitative results of ATTR deposition grading with JMP Pro (version 11.2.0; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Shojiro Ichimata; Data curation, Shojiro Ichimata; Formal analysis, Shojiro Ichimata; Funding acquisition, Shojiro Ichimata; Investigation, Shojiro Ichimata and Koji Yoshida; Methodology, Koji Yoshida and Keiichi Hirono; Project administration, Shojiro Ichimata; Resources, Yukiko Hata and Naoki Nishida; Supervision, Naoki Nishida; Validation, Naoki Nishida; Visualization, Shojiro Ichimata; Writing—original draft, Shojiro Ichimata; Writing—review & editing, Yukiko Hata, Koji Yoshida, Keiichi Hirono and Naoki Nishida.

Funding

This study was supported in part by a JSPS KAKENHI grant awarded to Shojiro Ichimata (grant number JP20K18979).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Toyama University (I2020006) and followed the ethical standards established in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and updated in 2008.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the nature of forensic autopsy. However, to address ethical considerations as thoroughly as possible, we obtained approval from the University of Toyama Ethics Committee (I2020006) and posted an opt-out statement regarding the research on our department’s website (http://www.med.u-toyama.ac.jp/legal/for_family.html).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms. Miyuki Maekawa for her technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

AANF, amyloid atrial natriuretic factor; AS, atrial septum; ATTR, amyloid transthyretin; AVN, atrioventricular node; CA, cardiac amyloidosis; IHC, immunohistochemistry; LA, left atrium; LAA, left atrial appendage; pCR, phenol Congo red; RA, right atrium; RAA, right atrial appendage; SAN, sinoatrial node; SCD, sudden cardiac death; VS, ventricular septum

References

- Buxbaum, J. N.; Dispenzieri, A.; Eisenberg, D. S.; Fandrich, M.; Merlini, G.; Saraiva, M. J. M.; Sekijima, Y.; Westermark, P. , Amyloid nomenclature 2022: update, novel proteins, and recommendations by the International Society of Amyloidosis (ISA) Nomenclature Committee. Amyloid 2022, 29(4), 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wechalekar, A. D.; Gillmore, J. D.; Hawkins, P. N. , Systemic amyloidosis. The Lancet 2016, 387(10038), 2641–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, B. T.; Mereuta, O. M.; Dasari, S.; Fayyaz, A. U.; Theis, J. D.; Vrana, J. A.; Grogan, M.; Dogan, A.; Dispenzieri, A.; Edwards, W. D.; Kurtin, P. J.; Maleszewski, J. J. , Correlation of histomorphological pattern of cardiac amyloid deposition with amyloid type: a histological and proteomic analysis of 108 cases. Histopathology 2016, 68(5), 648–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naiki, H.; Yamaguchi, A.; Sekijima, Y.; Ueda, M.; Ohashi, K.; Hatakeyama, K.; Ikeda, Y.; Hoshii, Y.; Shintani-Domoto, Y.; Miyagawa-Hayashino, A.; Tsujikawa, H.; Endo, J.; Arai, T.; Ando, Y. , Steep increase in the number of transthyretin-positive cardiac biopsy cases in Japan: evidence obtained by the nation-wide pathology consultation for the typing diagnosis of amyloidosis. Amyloid 2023, 30(3), 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, A.; Tasaki, M.; Ueda, M.; Ando, Y.; Naiki, H. , Epidemiological study of the subtype frequency of systemic amyloidosis listed in the Annual of the Pathological Autopsy Cases in Japan. Pathol. Int. 2024, 74(2), 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurer, M. S.; Schwartz, J. H.; Gundapaneni, B.; Elliott, P. M.; Merlini, G.; Waddington-Cruz, M.; Kristen, A. V.; Grogan, M.; Witteles, R.; Damy, T.; Drachman, B. M.; Shah, S. J.; Hanna, M.; Judge, D. P.; Barsdorf, A. I.; Huber, P.; Patterson, T. A.; Riley, S.; Schumacher, J.; Stewart, M.; Sultan, M. B.; Rapezzi, C.; Investigators, A.-A. S. , Tafamidis treatment for patients with transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379(11), 1007–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruberg, F. L.; Maurer, M. S. , Cardiac amyloidosis due to transthyretin protein: a review. JAMA 2024, 331(9), 778–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okada, A.; Kakuta, T.; Tadokoro, N.; Tateishi, E.; Morita, Y.; Kitai, T.; Amaki, M.; Kanzaki, H.; Ohta-Ogo, K.; Ikeda, Y.; Fukushima, S.; Fujita, T.; Kusano, K.; Noguchi, T.; Izumi, C. , Transthyretin derived amyloid deposits in the atrium and the aortic valve: insights from multimodality evaluations and mid-term follow up. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2023, 23(1), 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singulane, C. C.; Slivnick, J. A.; Addetia, K.; Asch, F. M.; Sarswat, N.; Soulat-Dufour, L.; Mor-Avi, V.; Lang, R. M. , Prevalence of right atrial impairment and association with outcomes in cardiac amyloidosis. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2022, 35(8), 829–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poterucha, T. J.; Maurer, M. S. , Too Stiff But Still Got Rhythm: Left atrial myopathy and transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2022, 15(1), 30–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandera, F.; Martone, R.; Chacko, L.; Ganesananthan, S.; Gilbertson, J. A.; Ponticos, M.; Lane, T.; Martinez-Naharro, A.; Whelan, C.; Quarta, C.; Rowczenio, D.; Patel, R.; Razvi, Y.; Lachmann, H.; Wechelakar, A.; Brown, J.; Knight, D.; Moon, J.; Petrie, A.; Cappelli, F.; Guazzi, M.; Potena, L.; Rapezzi, C.; Leone, O.; Hawkins, P. N.; Gillmore, J. D.; Fontana, M. , Clinical importance of left atrial infiltration in cardiac transthyretin amyloidosis. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2022, 15(1), 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichimata, S.; Hata, Y.; Hirono, K.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Nishida, N. , Clinicopathological features of clinically undiagnosed sporadic transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis: a forensic autopsy-based series. Amyloid 2021, 28(2), 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner, I.; Hajkova, P. , Patterns of isolated atrial amyloid: a study of 100 hearts on autopsy. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2006, 15(5), 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawamura, S.; Takahashi, M.; Ishihara, T.; Uchino, F. , Incidence and distribution of isolated atrial amyloid: histologic and immunohistochemical studies of 100 aging hearts. Pathol. Int. 1995, 45(5), 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fayyaz, A. U.; Bois, M. C.; Dasari, S.; Padmanabhan, D.; Vrana, J. A.; Stulak, J. M.; Edwards, W. D.; Kurtin, P. J.; Asirvatham, S. J.; Grogan, M.; Maleszewski, J. J. , Amyloidosis in surgically resected atrial appendages: a study of 345 consecutive cases with clinical implications. Mod. Pathol. 2020, 33(5), 764–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuyama, N.; Takashio, S.; Nakamura, K.; Nishigawa, K.; Hanatani, S.; Usuku, H.; Yamamoto, E.; Ueda, M.; Fukui, T.; Tsujita, K. , Coexisting transthyretin and atrial natriuretic peptide amyloid on left atrium in transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy. Journal of Cardiology Cases 2024, 29(6), 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gimelli, A.; Aimo, A.; Vergaro, G.; Genovesi, D.; Santonato, V.; Kusch, A.; Emdin, M.; Marzullo, P. , Cardiac sympathetic denervation in wild-type transthyretin amyloidosis. Amyloid 2020, 27(4), 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coutinho, M. C. A.; Cortez-Dias, N.; Cantinho, G.; Conceição, I.; Oliveira, A.; Bordalo e Sá, A.; Gonçalves, S.; Almeida, A. G.; de Carvalho, M.; Diogo, A. N. , Reduced myocardial 123-iodine metaiodobenzylguanidine uptake. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2013, 6(5), 627–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javanshiri, K.; Drakenberg, T.; Haglund, M.; Englund, E. , Sudden cardiac death in synucleinopathies. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2023, 82(3), 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hitosugi, M.; Takatsu, A.; Kinugasa, Y.; Takao, H. , Estimation of normal heart weight in Japanese subjects: development of a simplified normal heart weight scale. Leg. Med. (Tokyo) 1999, 1(2), 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishizawa, R. H.; Kawano, H.; Yoshimuta, T.; Eguchi, C.; Kojima, S.; Minami, T.; Sato, D.; Eguchi, M.; Okano, S.; Ikeda, S.; Ueda, M.; Maemura, K. , Effects of tafamidis on the left ventricular and left atrial strain in patients with wild-type transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2024, 25(5), 678–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rausch, K.; Scalia, G. M.; Sato, K.; Edwards, N.; Lam, A. K.; Platts, D. G.; Chan, J. , Left atrial strain imaging differentiates cardiac amyloidosis and hypertensive heart disease. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2021, 37(1), 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand, A.; Frumkin, D.; Hubscher, A.; Dreger, H.; Stangl, K.; Baldenhofer, G.; Knebel, F. , Phasic left atrial strain analysis to discriminate cardiac amyloidosis in patients with unclear thick heart pathology. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2021, 22(6), 680–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monte, I. P.; Faro, D. C.; Trimarchi, G.; de Gaetano, F.; Campisi, M.; Losi, V.; Teresi, L.; Di Bella, G.; Tamburino, C.; de Gregorio, C. , Left atrial strain imaging by speckle tracking echocardiography: The supportive diagnostic value in cardiac amyloidosis and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis 2023, 10(6), 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, S.; Brayne, C. , Do anti-amyloid beta protein antibody cross reactivities confound Alzheimer disease research? J Negat Results Biomed 2017, 16(1), 1. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson, A.; Malmstrom, S.; Westermark, P. , Signs of cross-seeding: aortic medin amyloid as a trigger for protein AA deposition. Amyloid 2011, 18(4), 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcoux, J.; Mangione, P. P.; Porcari, R.; Degiacomi, M. T.; Verona, G.; Taylor, G. W.; Giorgetti, S.; Raimondi, S.; Sanglier-Cianferani, S.; Benesch, J. L.; Cecconi, C.; Naqvi, M. M.; Gillmore, J. D.; Hawkins, P. N.; Stoppini, M.; Robinson, C. V.; Pepys, M. B.; Bellotti, V. , A novel mechano-enzymatic cleavage mechanism underlies transthyretin amyloidogenesis. EMBO Mol. Med. 2015, 7(10), 1337–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milandri, A.; Farioli, A.; Gagliardi, C.; Longhi, S.; Salvi, F.; Curti, S.; Foffi, S.; Caponetti, A. G.; Lorenzini, M.; Ferlini, A.; Rimessi, P.; Mattioli, S.; Violante, F. S.; Rapezzi, C. , Carpal tunnel syndrome in cardiac amyloidosis: implications for early diagnosis and prognostic role across the spectrum of aetiologies. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2020, 22(3), 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichimata, S.; Hata, Y.; Yoshida, K.; Nishida, N. , Autopsy of a multiple lobar hemorrhage case with amyloid-beta-related angiitis. Neuropathology 2020, 40(3), 280–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichimata, S.; Aikawa, A.; Sugishita, N.; Katoh, N.; Kametani, F.; Tagawa, H.; Handa, Y.; Yazaki, M.; Sekijima, Y.; Ehara, T.; Nishida, N.; Ishizawa, S. , Enterocolic granulomatous phlebitis associated with epidermal growth factor-containing fibulin-like extracellular matrix protein 1 deposition and focal amyloid properties: A case report. Pathol. Int. 2024, 74(3), 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichimata, S.; Hata, Y.; Nomoto, K.; Nishida, N. , Transthyretin-derived amyloid (ATTR) and sarcoidosis: Does ATTR deposition cause a granulomatous inflammatory response in older adults with sarcoidosis? Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2024, 107624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontana, M.; Gilbertson, J.; Verona, G.; Riefolo, M.; Slamova, I.; Leone, O.; Rowczenio, D.; Botcher, N.; Ioannou, A.; Patel, R. K.; Razvi, Y.; Martinez-Naharro, A.; Whelan, C. J.; Venneri, L.; Duhlin, A.; Canetti, D.; Ellmerich, S.; Moon, J. C.; Kellman, P.; Al-Shawi, R.; McCoy, L.; Simons, J. P.; Hawkins, P. N.; Gillmore, J. D. , Antibody-associated reversal of ATTR amyloidosis-related cardiomyopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388(23), 2199–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapezzi, C.; Riva, L.; Quarta, C. C.; Perugini, E.; Salvi, F.; Longhi, S.; Ciliberti, P.; Pastorelli, F.; Biagini, E.; Leone, O.; Cooke, R. M.; Bacchi-Reggiani, L.; Ferlini, A.; Cavo, M.; Merlini, G.; Perlini, S.; Pasquali, S.; Branzi, A. , Gender-related risk of myocardial involvement in systemic amyloidosis. Amyloid 2008, 15(1), 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanskanen, M.; Peuralinna, T.; Polvikoski, T.; Notkola, I. L.; Sulkava, R.; Hardy, J.; Singleton, A.; Kiuru-Enari, S.; Paetau, A.; Tienari, P. J.; Myllykangas, L. , Senile systemic amyloidosis affects 25% of the very aged and associates with genetic variation in alpha2-macroglobulin and tau: a population-based autopsy study. Ann. Med. 2008, 40(3), 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caponetti, A. G.; Rapezzi, C.; Gagliardi, C.; Milandri, A.; Dispenzieri, A.; Kristen, A. V.; Wixner, J.; Maurer, M. S.; Garcia-Pavia, P.; Tournev, I.; Plante-Bordeneuve, V.; Chapman, D.; Amass, L.; Investigators, T. , Sex-related risk of cardiac involvement in hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis: Insights from THAOS. JACC Heart Fail 2021, 9(10), 736–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, C. M.; LoRusso, S.; Dispenzieri, A.; Kristen, A. V.; Maurer, M. S.; Rapezzi, C.; Lairez, O.; Drachman, B.; Garcia-Pavia, P.; Grogan, M.; Chapman, D.; Amass, L.; investigators, T. , Sex Differences in Wild-Type Transthyretin Amyloidosis: An Analysis from the Transthyretin Amyloidosis Outcomes Survey (THAOS). Cardiol Ther 2022, 11(3), 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nebel, R. A.; Aggarwal, N. T.; Barnes, L. L.; Gallagher, A.; Goldstein, J. M.; Kantarci, K.; Mallampalli, M. P.; Mormino, E. C.; Scott, L.; Yu, W. H.; Maki, P. M.; Mielke, M. M. , Understanding the impact of sex and gender in Alzheimer’s disease: A call to action. Alzheimers Dement 2018, 14(9), 1171–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichimata, S.; Yoshida, K.; Li, J.; Rogaeva, E.; Lang, A. E.; Kovacs, G. G. , The molecular spectrum of amyloid-beta (Abeta) in neurodegenerative diseases beyond Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Pathol. 2024, 34(1), e13210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasaki, M.; Lavatelli, F.; Obici, L.; Obayashi, K.; Miyamoto, T.; Merlini, G.; Palladini, G.; Ando, Y.; Ueda, M. , Age-related amyloidosis outside the brain: A state-of-the-art review. Ageing Res Rev 2021, 70, 101388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, T.; Maurer, M. S.; Suhr, O. B. , THAOS - The transthyretin amyloidosis outcomes survey: Initial report on clinical manifestations in patients with hereditary and wild-type transthyretin amyloidosis. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2013, 29(1), 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, L.; Margeta, M.; Layzer, R. , Amyloid polyneuropathy caused by wild-type transthyretin. Muscle Nerve 2015, 52(1), 146–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashita, T.; Ueda, M.; Misumi, Y.; Masuda, T.; Nomura, T.; Tasaki, M.; Takamatsu, K.; Sasada, K.; Obayashi, K.; Matsui, H.; Ando, Y. , Genetic and clinical characteristics of hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis in endemic and non-endemic areas: experience from a single-referral center in Japan. J. Neurol. 2018, 265(1), 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishii, W.; Matsuda, M.; Nakamura, N.; Katsumata, S.; Toriumi, H.; Suzuki, A.; Ikeda, S.-i. , Phenol Congo Red Staining Enhances the Diagnostic Value of Abdominal Fat Aspiration Biopsy in Reactive AA Amyloidosis Secondary to Rheumatoid Arthritis. Intern. Med. 2003, 42(5), 400–405. [Google Scholar]

- Ueda, M.; Horibata, Y.; Shono, M.; Misumi, Y.; Oshima, T.; Su, Y.; Tasaki, M.; Shinriki, S.; Kawahara, S.; Jono, H.; Obayashi, K.; Ogawa, H.; Ando, Y. , Clinicopathological features of senile systemic amyloidosis: an ante- and post-mortem study. Mod. Pathol. 2011, 24(12), 1533–1544. [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; Tinevez, J. Y.; White, D. J.; Hartenstein, V.; Eliceiri, K.; Tomancak, P.; Cardona, A. , Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods 2012, 9(7), 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichimata, S.; Kim, A.; Nishida, N.; Kovacs, G. G. , Lack of difference between amyloid-beta burden at gyral crests and sulcal depths in diverse neurodegenerative diseases. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2023, 49(1), e12869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichimata, S.; Martinez-Valbuena, I.; Lee, S.; Li, J.; Karakani, A. M.; Kovacs, G. G. , Distinct Molecular Signatures of Amyloid-Beta and Tau in Alzheimer’s Disease Associated with Down Syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24(14), 11596. [Google Scholar]

- Milenkovic, I.; Jarc, J.; Dassler, E.; Aronica, E.; Iyer, A.; Adle-Biassette, H.; Scharrer, A.; Reischer, T.; Hainfellner, J. A.; Kovacs, G. G. , The physiological phosphorylation of tau is critically changed in fetal brains of individuals with Down syndrome. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2018, 44(3), 314–327. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Representative microphotographs of multinucleated giant cells surrounding transthyretin-derived amyloid (ATTR) deposits. (a, b) Atrial septum; (c, d) left atrial appendage. (a, c) Phenol Congo red staining; (b, d) immunohistochemistry (IHC) for transthyretin. Multinucleated giant cells with lymphocytes surround the ATTR deposits. No clear fragmentation of ATTR deposits is observed. Scale bar = 100 μm (a–d).

Figure 1.

Representative microphotographs of multinucleated giant cells surrounding transthyretin-derived amyloid (ATTR) deposits. (a, b) Atrial septum; (c, d) left atrial appendage. (a, c) Phenol Congo red staining; (b, d) immunohistochemistry (IHC) for transthyretin. Multinucleated giant cells with lymphocytes surround the ATTR deposits. No clear fragmentation of ATTR deposits is observed. Scale bar = 100 μm (a–d).

Figure 2.

Severity of cardiac involvement in each region of the heart. (a–e) Semiquantitative grading of ATTR deposition; (f) semiquantitative grading of AANF deposition; (g) quantitative grading of ATTR deposition in the myocardium. (a) Ventricular septum (VS); (b) atrial septum (AS); (c) superior vena cava (SVC); (d) right atrium (RA) and left atrium (LA); (e) right atrial appendage (RAA) and left atrial appendage (LAA); (f) AS, both atrial regions, and SVC; (g) VS, AS, both atrial regions, and SVC. Abbreviations: E, endocardium; EL, endocardium of the left side; ER, endocardium of the right side; I, interstitium; V, vessel. ** p < 0.01.

Figure 2.

Severity of cardiac involvement in each region of the heart. (a–e) Semiquantitative grading of ATTR deposition; (f) semiquantitative grading of AANF deposition; (g) quantitative grading of ATTR deposition in the myocardium. (a) Ventricular septum (VS); (b) atrial septum (AS); (c) superior vena cava (SVC); (d) right atrium (RA) and left atrium (LA); (e) right atrial appendage (RAA) and left atrial appendage (LAA); (f) AS, both atrial regions, and SVC; (g) VS, AS, both atrial regions, and SVC. Abbreviations: E, endocardium; EL, endocardium of the left side; ER, endocardium of the right side; I, interstitium; V, vessel. ** p < 0.01.

Figure 3.

Representative microphotographs of the left-side predominant deposition pattern of ATTR in the atrial regions. (a–h) Transthyretin IHC (patient 8). (a, b) Right atrium; (c, d) right atrial appendage; (e, f) left atrium; (g, h) left atrial appendage. Panels b, d, f, and h are a higher magnification view indicated with a black square in panels a, c, e, and g, respectively. ATTR is not deposited in the right atrial regions (a–d) but was severely deposited in the left atrial regions (e–h). Scale bar = 3 mm (a, c, e, g); 200 μm (b, d, f, h).

Figure 3.

Representative microphotographs of the left-side predominant deposition pattern of ATTR in the atrial regions. (a–h) Transthyretin IHC (patient 8). (a, b) Right atrium; (c, d) right atrial appendage; (e, f) left atrium; (g, h) left atrial appendage. Panels b, d, f, and h are a higher magnification view indicated with a black square in panels a, c, e, and g, respectively. ATTR is not deposited in the right atrial regions (a–d) but was severely deposited in the left atrial regions (e–h). Scale bar = 3 mm (a, c, e, g); 200 μm (b, d, f, h).

Figure 4.

Representative microphotographs of nodular deposits in the LA evaluated using double IHC for ANF and transthyretin. (a–f) Patient 10. (a, b) Phenol Congo red staining under bright field (a) and polarised light (b). Single IHC for ANF (c) and transthyretin (d). Double IHC for ANF and transthyretin (e, f). (a–d) Nodular lesions observed in the right half are positive for ANF but negative for transthyretin, whereas those observed in the left half are negative for ANF but positive for transthyretin. (e, f) Double IHC shows no clear colocalisation of the two (ANF, brown; transthyretin, green) in the myocardial layer (e) and endocardial interstitium (f). Scale bar = 100 μm (a–f).

Figure 4.

Representative microphotographs of nodular deposits in the LA evaluated using double IHC for ANF and transthyretin. (a–f) Patient 10. (a, b) Phenol Congo red staining under bright field (a) and polarised light (b). Single IHC for ANF (c) and transthyretin (d). Double IHC for ANF and transthyretin (e, f). (a–d) Nodular lesions observed in the right half are positive for ANF but negative for transthyretin, whereas those observed in the left half are negative for ANF but positive for transthyretin. (e, f) Double IHC shows no clear colocalisation of the two (ANF, brown; transthyretin, green) in the myocardial layer (e) and endocardial interstitium (f). Scale bar = 100 μm (a–f).

Figure 5.

Ward’s hierarchical cluster analysis using the semiquantitative histopathological deposition grading. Wards hierarchical cluster analysis using the semiquantitative ATTR deposition grading. Dendrogram of cluster analysis (upper panel) and amyloid deposition distribution and severity in each area (lower panel). Abbreviations: E, endocardium; EL, endocardium of the left side; ER, endocardium of the right side; I, interstitium; V, vessel.

Figure 5.

Ward’s hierarchical cluster analysis using the semiquantitative histopathological deposition grading. Wards hierarchical cluster analysis using the semiquantitative ATTR deposition grading. Dendrogram of cluster analysis (upper panel) and amyloid deposition distribution and severity in each area (lower panel). Abbreviations: E, endocardium; EL, endocardium of the left side; ER, endocardium of the right side; I, interstitium; V, vessel.

Figure 6.

Representative microphotographs of ATTR and AANF deposition grading employed in this study. (a–l) IHC for transthyretin; (m–t) pCR staining under bright field (m–p) and polarised light observation (q–t). Scale bar = 200 μm (a–t).

Figure 6.

Representative microphotographs of ATTR and AANF deposition grading employed in this study. (a–l) IHC for transthyretin; (m–t) pCR staining under bright field (m–p) and polarised light observation (q–t). Scale bar = 200 μm (a–t).

Figure 7.

Representative microphotographs of AANF deposition with nodular deposits. (a–d) Left atrium (Case 7). (a, b) pCR staining under bright field (a) and polarized light (b) observation; IHC for ANF (c) and transthyretin (d). (a) Both nodular and pericellular deposition patterns are observed. (b) Both lesions show clear apple-green birefringence under polarized light. However, although nodular deposits exhibit moderate to strong immunoreactivity for ANF, pericellular deposits show very weak immunoreactivity. (d) These deposits are negative for transthyretin. Scale bar = 200 μm (a–d).

Figure 7.

Representative microphotographs of AANF deposition with nodular deposits. (a–d) Left atrium (Case 7). (a, b) pCR staining under bright field (a) and polarized light (b) observation; IHC for ANF (c) and transthyretin (d). (a) Both nodular and pericellular deposition patterns are observed. (b) Both lesions show clear apple-green birefringence under polarized light. However, although nodular deposits exhibit moderate to strong immunoreactivity for ANF, pericellular deposits show very weak immunoreactivity. (d) These deposits are negative for transthyretin. Scale bar = 200 μm (a–d).

Figure 8.

Representative microphotographs of AANF deposition in the AS. (a, c, d, f, g) pCR staining under bright field (a, c, f) and polarized light (d, g) observation; IHC for ANF (b, e, h). (a) Congo reg-positive deposition is observed predominantly in the LA side compared to the RA side. Note that AANF deposition is predominantly observed in the subendocardial myocardial layer on both the left and right sides. (b) However, in the ANF-IHC specimen, the difference is not obvious. In higher magnification view, on the RA side, AANF deposits are observed that incompletely surround the cardiomyocytes (arrowhead indicates ATTR deposits) (c–e). In contrast, on the LA side, AANF deposits are observed that completely surround the cardiomyocytes (f–h). Nevertheless, note that the immunoreactivity of ANF on the RA side (e) is equal to or slightly weaker than that on the LA side (h). Scale bar = 1 mm (a, b); 100 μm (c–h).

Figure 8.

Representative microphotographs of AANF deposition in the AS. (a, c, d, f, g) pCR staining under bright field (a, c, f) and polarized light (d, g) observation; IHC for ANF (b, e, h). (a) Congo reg-positive deposition is observed predominantly in the LA side compared to the RA side. Note that AANF deposition is predominantly observed in the subendocardial myocardial layer on both the left and right sides. (b) However, in the ANF-IHC specimen, the difference is not obvious. In higher magnification view, on the RA side, AANF deposits are observed that incompletely surround the cardiomyocytes (arrowhead indicates ATTR deposits) (c–e). In contrast, on the LA side, AANF deposits are observed that completely surround the cardiomyocytes (f–h). Nevertheless, note that the immunoreactivity of ANF on the RA side (e) is equal to or slightly weaker than that on the LA side (h). Scale bar = 1 mm (a, b); 100 μm (c–h).

Figure 9.

Representative microphotographs of AANF deposition without congophilia. (a–d) LA. (a, b) IHC for ANF; (c, d) pCR staining under bright field (c) and polarized light (d) observation. (a) The upper half of the panel (the endocardium side) shows ANF deposition around cardiomyocytes. In contrast, in the lower half, ANF immunoreactivity is observed in the cytoplasm of the cardiomyocytes. (b) Strong ANF immunoreactivity is observed around cardiomyocytes. (c, d) However, these deposits are negative for pCR staining and show no birefringence. Scale bar = 100 μm (a–d).

Figure 9.

Representative microphotographs of AANF deposition without congophilia. (a–d) LA. (a, b) IHC for ANF; (c, d) pCR staining under bright field (c) and polarized light (d) observation. (a) The upper half of the panel (the endocardium side) shows ANF deposition around cardiomyocytes. In contrast, in the lower half, ANF immunoreactivity is observed in the cytoplasm of the cardiomyocytes. (b) Strong ANF immunoreactivity is observed around cardiomyocytes. (c, d) However, these deposits are negative for pCR staining and show no birefringence. Scale bar = 100 μm (a–d).

Table 1.

Summary of the clinical and pathological features of ATTR-CA cases.

| # | Age | Sex | BH | BW | BMI | HW | NHW* | Ratio** | C/TD | HT | HL | DM | ART | CHF | CAS |

| 1 | 81 | F | 147 | 43.6 | 20.2 | 346 | 242 | 1.4 | HyT/Sui | Neg | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | Rt |

| 2 | 87 | F | 147 | 36.3 | 16.8 | 321 | 218 | 1.5 | Dro/Sui | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| 3 | 80 | F | 146 | 45.9 | 21.5 | 387 | 248 | 1.6 | HyT/Acc | Pos | Neg | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| 4 | 79 | F | 164 | 72 | 26.8 | 584 | 361 | 1.6 | Dro/Acc | Pos | Neg | Neg | Af | Neg | Neg |

| 5 | 82 | M | 160 | 53.1 | 20.7 | 556 | 317 | 1.8 | HyT/Ill | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| 6 | 90 | F | 151 | 39.1 | 17.1 | 336 | 234 | 1.4 | HyT/Acc | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| 7 | 89 | M | 158 | 40.4 | 16.2 | 330 | 265 | 1.2 | Dro/Acc | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| 8 | 78 | M | 156 | 65.3 | 26.8 | 550 | 350 | 1.6 | CA/Ill | Pos | Neg | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| 9 | 90 | F | 148 | 44.7 | 20.4 | 306 | 247 | 1.2 | Dro/Acc | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| 10 | 97 | F | 153 | 51.5 | 22.0 | 356 | 278 | 1.3 | HS/Acc | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| 11 | 79 | F | 153 | 49.8 | 21.3 | 302 | 272 | 1.1 | Burn/Acc | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| 12 | 83 | M | 158 | 41.5 | 16.6 | 383 | 269 | 1.4 | Dro/Sui | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| 13 | 85 | F | 145 | 35.2 | 16.7 | 283 | 211 | 1.3 | Burn/Acc | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Lt |

| 14 | 94 | M | 159 | 29.4 | 11.6 | 379 | 219 | 1.7 | Dro/Acc | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| 15 | 81 | M | 161 | 58.5 | 22.6 | 450 | 339 | 1.3 | Dro/Acc | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| 16 | 85 | M | 157 | 51.8 | 21.0 | 364 | 306 | 1.2 | Dro/Sui | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| 17 | 89 | M | 158 | 44.2 | 17.7 | 304 | 280 | 1.1 | HyT/Acc | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Lt |

| 18 | 80 | F | 152 | 69.6 | 30.1 | 408 | 329 | 1.2 | Dro/Acc | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| 19 | 89 | M | 159 | 37.4 | 14.8 | 435 | 254 | 1.7 | DOD/Sui | Pos | Neg | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| 20 | 93 | F | 144 | 41.8 | 20.2 | 365 | 232 | 1.6 | ACD/Ill | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | Rt, Lt |

Abbreviations: Acc, accident; ACD, acute cardiac dysfunction (excluding CA); Af, atrial fibrillation; ART, arrythmia; BH, body height (cm); BW, body weight (kg); BMI, body mass index; CAS, coronary artery stenosis (≥75%); CHF, chronic heart failure; DM, diabetes mellitus; F, female; HL, hyperlipidemia; HM, ; HT, hypertension; HW, heart weight; Ill, illness; Lt, left; M, male; NA, not available; NHW, normalised heart weight (g); Rt, right; Sui, suicide. * Values were calculated with reference to the literature [20]. ** HW/NHW.

Table 2.

Summary of the positive deposition rates of ATTR and AANF in each area.

| ATTR deposition rate (%) | Total # of cases = 20 |

| VS (E/V/I) | 4 (20)/10 (50)/19 (95) |

| AS (ER/EL/V/I) | 16 (80)**/7 (35)/10 (50)/17 (85) |

| RA (E/V/I) | 11 (55)/12 (60)/14 (70) |

| RAA (E/V/I) | 12 (60)/9 (45)/12 (60) |

| LA (E/V/I) | 17 (85)/17 (85)/20 (100)* |

| LAA (E/V/I) | 14 (70)/10 (50)/20 (100)** |

| SVC (E/V/I) | 14 (70)/6 (30)/18 (90) |

| Sinoatrial node | 3 (15) |

| Atrioventricular node | 0 |

| Neural/perineural deposition | 2 (10)/6 (30) |

| AANF deposition rate (%) | Total # of cases = 20 |

| AS | 17 (85) |

| RA | 18 (90) |

| RAA | 19 (95) |

| LA | 19 (95) |

| LAA | 20 (100) |

| SVC | 13 (65) |

Abbreviations: AS, atrial septum; E, endocardium; EL, endocardium in the left side; ER, endocardium in the right side; I, interstitium; LA, left atrium; LAA, left atrial appendage; RA, right atrium; RAA, right atrial appendage; SVC, superior vena cava; V, vessel; VS, ventricular septum. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01, right side vs. left side, compared using the Fisher’s exact test.

Table 3.

Summary of clinical and pathological data in patients with definite or possible constipation.

Table 3.

Summary of clinical and pathological data in patients with definite or possible constipation.

| Group 1 (N = 8) | Group 2 (N = 9) | Group 3 (N = 3) | p value* | ||

| Sex (F/M) | 7/1 | 2/7 | 2/1 | 0.02/0.49/0.24 | |

| Age (range) | 83.9 ± 5.4 (79–93) | 85.7 ± 5.3 (78–97) | 89.7 ± 3.7 (85–94) | 0.24 (1.00/0.28/0.67) | |

| N/PN involvement | 1 (13) | 4 (44) | 1 (33) | 0.29/0.49/1 | |

| ATTR deposition severity | |||||

| VS | E | 0 | 0.6 ± 0.7 (0–2) | 0 | 0.06 (0.08/1/0.32) |

| V | 0.3 ± 0.4 (0–1) | 1.1 ± 1.2 (0–3) | 3.0 ± 0.8 (2–4) | 0.02 (0.50/0.01/0.18) | |

| I-SQ | 1.6 ± 0.7 (1–3) | 3.3 ± 0.7 (2–4) | 1.3 ± 1.2 (0–3) | <0.01 (<0.01/1/0.06) | |

| I-Q | 2.9 ± 3.1 (0–9.2) | 15.6 ± 7.4 (2.3–24.9) | 3.2 ± 4.5 (0–9.6) | <0.01 (<0.01/1/0.03) | |

| AS | ER | 1.0 ± 1.0 (0–3) | 3.4 ± 0.8 (2–4) | 2.7 ± 1.9 (0–4) | <0.01 (<0.01/0.34/1) |

| EL | 0 | 1.1 ± 1.1 (0–3) | 0.3 ± 0.5 (0–1) | 0.02 (0.02/1/0.77) | |

| V | 0.1 ± 0.3 (0–1) | 0.8 ± 0.6 (0–2) | 2.0 ± 0.8 (1–3) | <0.01 (0.16/<0.01/0.32) | |

| I-SQ | 0.9 ± 0.6 (0–2) | 3.4 ± 0.7 (2–4) | 2.0 ± 1.6 (0–4) | <0.01 (<0.01/0.80/0.50) | |

| I-Q | 0.6 ± 0.8 (0–2.4) | 14.7 ± 5.2 (6.1–23.5) | 8.6 ± 8.9 (0–20.8) | <0.01 (<0.01/0.65/0.68) | |

| RA | E | 0.4 ± 0.7 (0–2) | 2.0 ± 1.2 (0–4) | 0.3 ± 0.5 (0–1) | 0.02 (0.02/1/0.16) |

| V | 0.4 ± 0.7 (0–2) | 1.6 ± 1.1 (0–3) | 2.0 ± 0.8 (1–3) | 0.03 (0.09/0.09/1) | |

| I-SQ | 0.6 ± 0.5 (0–1) | 1.8 ± 1.3 (0–4) | 0.3 ± 0.5 (0–1) | 0.047 (0.15/1/0.11) | |

| I-Q | 0.2 ± 0.3 (0–0.7) | 5.3 ± 6.9 (0–19.9) | 0.2 ± 0.3 (0–0.7) | 0.04 (0.07/1/0.20) | |

| RAA | E | 0.4 ± 0.5 (0–1) | 1.9 ± 1.1 (0–4) | 0.3 ± 0.5 (0–1) | 0.01 (0.02/1/0.11) |

| V | 0 | 1.0 ± 1.2 (0–4) | 3.0 ± 0.8 (2–4) | <0.01 (0.07/<0.01/0.24) | |

| I-SQ | 0.5 ± 0.5 (0–1) | 1.2 ± 0.8 (0–2) | 0.3 ± 0.5 (0–1) | 0.10 (0.20/1/0.27) | |

| I-Q | 0.1 ± 0.1 (0–0.2) | 2.5 ± 2.6 (0–7.1) | 0.0 ± 0.1 (0–0.1) | 0.03 (0.053/1/0.18) | |

| LA | E | 0.8 ± 0.7 (0–2) | 2.3 ± 0.7 (1–3) | 2.0 ± 0.0 (2) | <0.01 (<0.01/0.18/1) |

| V | 0.6 ± 0.5 (0–1) | 1.7 ± 0.9 (1–3) | 3.0 ± 0.8 (2–4) | <0.01 (0.11/<0.01/0.34) | |

| I-SQ | 1.5 ± 1.0 (1–4) | 3.6 ± 0.7 (2–4) | 2.0 ± 0.8 (1–3) | <0.01 (<0.01/1/0.23) | |

| I-Q | 2.4 ± 4.3 (0.1–13.8) | 11.9 ± 5.9 (1.7–18.4) | 5.4 ± 3.8 (0.1–9.0) | <0.01 (<0.01/1/0.27) | |

| LAA | E | 0.4 ± 0.5 (0–1) | 2.0 ± 1.3 (0–4) | 0.7 ± 0.5 (0–1) | 0.02 (0.02/1/0.47) |

| V | 0.1 ± 0.3 (0–1) | 1.0 ± 0.9 (0–3) | 3.0 ± 0.8 (2–4) | <0.01 (0.17/<0.01/0.19) | |

| I-SQ | 1.3 ± 0.4 (1–2) | 2.6 ± 0.7 (2–4) | 2.3 ± 1.2 (1–4) | <0.01 (<0.01/0.38/1) | |

| I-Q | 1.2 ± 1.4 (0–3.6) | 9.5 ± 5.8 (1.8–18.5) | 7.4 ± 6.8 (0.1–16.5) | <0.01 (<0.01/0.44/1) | |

| SVC | E | 0.9 ± 1.1 (0–3) | 2.7 ± 1.2 (0–4) | 2.3 ± 1.7 (0–4) | 0.06 (0.06/0.50/1) |

| V | 0 | 0.6 ± 0.8 (0–2) | 2.0 ± 0.8 (1–3) | <0.01 (0.50/<0.01/0.08) | |

| I-SQ | 0.9 ± 0.3 (0–1) | 2.1 ± 1.0 (1–4) | 2.3 ± 1.7 (0–4) | 0.045 (0.053/0.34/1) | |

| I-Q | 0.3 ± 0.5 (0–1.5) | 6.5 ± 5.4 (0.5–17.0) | 8.6 ± 7.7 (0–18.7) | 0.02 (0.02/0.30/1) | |

| AANF deposition severity | |||||

| AS | 1.4 ± 1.0 (0–3) | 1.8 ± 1.0 (1–4) | 1.3 ± 0.9 (0–2) | 0.86 (1/1/1) | |

| RA | 1.5 ± 0.9 (0–3) | 1.3 ± 0.7 (0–2) | 1.3 ± 0.5 (1–2) | 0.91 (1/1/1) | |

| RAA | 2.0 ± 1.0 (0–3) | 1.7 ± 0.5 (1–2) | 2.0 ± 0.8 (1–3) | 0.53 (0.84/1/1) | |

| LA | 1.9 ± 1.1 (0–4) | 1.7 ± 0.7 (1–3) | 2.7 ± 0.5 (2–3) | 0.16 (1/0.41/0.17) | |

| LAA | 2.3 ± 0.8 (1–3) | 2.1 ± 1.0 (1–4) | 2.3 ± 0.5 (2–3) | 0.87 (1/1/1) | |

| SVC | 0.6 ± 0.7 (0–2) | 0.7 ± 0.5 (0–1) | 1.0 ± 0.0 (1) | 0.52 (1/0.76/1) | |

Boldface signifies values that are statistically significant at p < 0.05. Abbreviations: N/PN, neural/perineural; Q, quantitative analysis result; SQ, semiquantitative analysis result.

| Semiquantitative ATTR deposition grading (range) | ||||

| Region | Female | Male | p value* | |

| Ventricular septum | Endocardium | 0.1 ± 0.3 (0–1) | 0.4 ± 0.7 (0–2) | 0.37 |

| Vessel | 0.9 ± 1.2 (0–3) | 1.2 ± 1.4 (0–4) | 0.66 | |

| Interstitium | 1.8 ± 1.1 (0–4) | 3.0 ± 0.9 (1–4) | 0.04 | |

| Atrial septum | Endocardium, right | 2.0 ± 1.7 (0–4) | 2.8 ± 1.3 (0–4) | 0.37 |

| Endocardium, left | 0.5 ± 0.9 (0–3) | 0.7 ± 0.9 (0–3) | 0.55 | |

| Vessel | 0.5 ± 0.7 (0–2) | 0.9 ± 1.0 (0–3) | 0.55 | |

| Interstitium | 1.7 ± 1.5 (0–4) | 2.8 ± 1.2 (0–4) | 0.15 | |

| Right atrium | Endocardium | 0.7 ± 1.1 (0–3) | 1.6 ± 1.3 (0–4) | 0.13 |

| Vessel | 0.9 ± 1.1 (0–3) | 1.4 ± 1.1 (0–3) | 0.30 | |

| Interstitium | 0.9 ± 1.1 (0–4) | 1.3 ± 1.2 (0–4) | 0.33 | |

| Right atrial appendage | Endocardium | 0.7 ± 1.0 (0–3) | 1.4 ± 1.2 (0–4) | 0.18 |

| Vessel | 0.9 ± 1.6 (0–4) | 0.9 ± 0.9 (0–3) | 0.41 | |

| Interstitium | 0.6 ± 0.6 (0–2) | 1.0 ± 0.8 (0–4) | 0.37 | |

| Left atrium | Endocardium | 1.3 ± 1.0 (0–3) | 2.1 ± 0.7 (1–3) | 0.08 |

| Vessel | 1.3 ± 1.2 (0–4) | 1.7 ± 0.9 (1–3) | 0.37 | |

| Interstitium | 2.0 ± 1.2 (1–4) | 3.1 ± 1.1 (1–4) | 0.07 | |

| Left atrial appendage | Endocardium | 0.7 ± 0.9 (0–3) | 1.7 ± 1.4 (0–4) | 0.13 |

| Vessel | 0.8 ± 1.2 (0–3) | 1.1 ± 1.2 (0–4) | 0.46 | |

| Interstitium | 1.9 ± 1.2 (1–4) | 2.1 ± 0.6 (1–3) | 0.37 | |

| Superior vena cava | Endocardium | 1.5 ± 1.5 (0–4) | 2.3 ± 1.4 (0–4) | 0.30 |

| Vessel | 0.5 ± 0.8 (0–2) | 0.7 ± 1.1 (0–3) | 0.77 | |

| Interstitium | 1.7 ± 1.2 (0–4) | 1.6 ± 1.1 (0–4) | 0.94 | |

| Semiquantitative AANF deposition grading (range) | ||||

| Region | Female | Male | p value | |

| Atrial septum | Interstitium | 1.5 ± 1.2 (0–4) | 1.7 ± 0.8 (1–3) | 0.71 |

| Right atrium | Interstitium | 1.5 ± 0.7 (0–2) | 1.3 ± 0.8 (0–3) | 0.30 |

| Right atrial appendage | Interstitium | 2.0 ± 0.9 (0–3) | 1.7 ± 0.7 (1–3) | 0.33 |

| Left atrium | Interstitium | 1.8 ± 0.7 (0–3) | 2.0 ± 1.1 (1–4) | 0.60 |

| Left atrial appendage | Interstitium | 2.4 ± 0.8 (1–3) | 2.0 ± 0.9 (1–4) | 1.00 |

| Superior vena cava | Interstitium | 0.6 ± 0.5 (0–1) | 0.8 ± 0.6 (0–2) | 0.71 |

| Quantitative ATTR deposition burden (%) | ||||

| Region | Female | Male | p value | |

| Ventricular septum | Interstitium | 5.3 ± 6.9 (0–24.0) | 12.8 ± 8.2 (0–24.9) | 0.056 |

| Atrial septum | Interstitium | 5.5 ± 7.7 (0–20.8) | 11.4 ± 7.5 (0–23.5) | 0.10 |

| Right atrium | Interstitium | 1.6 ± 4.3 (0–15.2) | 3.6 ± 6.1 (0–19.9) | 0.20 |

| Right atrial appendage | Interstitium | 0.4 ± 1.1 (0–4.0) | 2.1 ± 2.6 (0–7.1) | 0.20 |

| Left atrium | Interstitium | 4.3 ± 4.7 (0.1–13.8) | 10.6 ± 7.1 (0.1–18.4) | 0.04 |

| Left atrial appendage | Interstitium | 5.4 ± 6.8 (0–18.5) | 6.3 ± 4.3 (0.1–14.0) | 0.37 |

| Superior vena cava | Interstitium | 4.5 ± 6.3 (0–18.7) | 4.1 ± 5.0 (0–17.0) | 0.50 |

Boldface signifies that values are statistically significant at p < 0.05. * Female vs. male, compared using the Mann–Whitney U test.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Copyright: This open access article is published under a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license, which permit the free download, distribution, and reuse, provided that the author and preprint are cited in any reuse.

Current Challenges of Cardiac Amyloidosis Awareness Among Romanian Cardiologists

Robert Adam

et al.

,

2021

Autopsy for Medical Diagnostics of Sudden Unexpected Death: Cardiac Conduction System Findings

Giulia Ottaviani

et al.

,

2023

MDPI Initiatives

Important Links

© 2024 MDPI (Basel, Switzerland) unless otherwise stated