Preprint

Article

Variations and Claims in International Construction Projects in the MENA Region from Last Decade

Altmetrics

Downloads

82

Views

31

Comments

0

A peer-reviewed article of this preprint also exists.

supplementary.pdf (165.32KB )

Submitted:

16 July 2024

Posted:

17 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Alerts

Abstract

This study delves into the dynamics of 'Variations' and 'Claims' within construction projects, specifically under the FIDIC-Red Book 1999 framework. The study aims to identify, categorize, and devise mitigation strategies for key types of variations and claims aligning with the FIDIC conditions of contract. The research is drawing on inputs from construction industry professionals including contract administrators and project managers, focusing on the MENA region. This choice is driven by the region's extensive adoption of FIDIC standards and its rapidly growing construction sector. Data collection encompassed a questionnaire distributed to 80 industry experts predominantly through interviews that focused on countries like Saudi Arabia, UAE, Kuwait, and Egypt. These locations were chosen to reflect diverse construction practices and the involvement of international firms. Utilizing SPSS-V.25 for statistical analysis, the study uncovers the most prevalent and impactful causes of variations and claims, highlighting the critical need for managerial intervention. A key feature is the integration of scientometric analysis for a quantitative finding. A significant addition to the methodology is the implementation of a k-means clustering analysis. The survey had high internal consistency with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.97, and respondents reported frequent and significant claims like delayed drawings, ambiguous documents, and client changes. The results showed that effective claims management requires clear communication and balanced contracts, while poor design and contract documentation cause variations and claims. Spearman's correlation showed strong positive relationships between certain claim types and causes, emphasizing the importance of dealing with these factors to reduce claims. Most respondents said the survey could predict and reduce claims.

Keywords:

Subject: Engineering - Architecture, Building and Construction

1. Introduction

The construction industry plays a crucial role in gauging the economic health of a country; its success fosters development and stability, while its failure can negatively impact the economy [1,2,3]. According to market research conducted until 2020 for the “construction industry” worldwide, the study focuses on global construction forecasts up to the year 2020 and the evolution of the “construction industry” in all major countries. According to the CIC’s (Construction Intelligence Center) Global 50s (2010-2020), this encompasses over 50 of the world’s biggest and most significant markets. This is largely due to the significant investments made in infrastructure and buildings in these regions, despite fluctuations in oil prices and their vulnerability to economic growth [1]. The report also confirmed that the Asia-Pacific region accounts for a growing portion of the global construction industry, rising from 40% in 2010 to nearly 49% in 2020. “Variations” and “claims” are common in the construction industry due to requirements and needs, as well as the growing complexity of construction processes. However, construction industry contracts with huge funding values undergo many “variations” during the project’s, design, contracting, and construction stages [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. The primary objectives of this study are to identify and characterize contractual variants and raised claims, in compliance with the employer’s FIDIC-Red Book 1999 [9]. Additionally, we aim to identify the significant causes of these variations and claims and provide suggestions for their resolution.

Much research on construction project management has yet to address “variations” and “claims.” Abdelalim et al. [1,2,3,5,6] have improved risk management, quality control, and productivity. Still, there needs to be more focused research on systematically identifying and characterizing significant variations and claims under FIDIC contracts for construction conditions [9]. Existing studies [4,7,8] focus on risk factors rather than contractual issues, making it difficult to determine the causes of these variations and claims. Last, while some studies [9,10,11] suggest strategic management and risk mitigation, there is a clear need for targeted recommendations and practical solutions that directly address and prevent construction project variations and claims. This gap highlights the need for a more integrated and focused approach to studying variations and claims, aligned with contractual frameworks like FIDIC, to develop construction industry strategies. Based on feedback from construction professionals’ experience, clients, consultants, contractors, and experts advocate for the use of survey questionnaires. Other research has tried to find “variations” and “claims” in the terms of the contract for the construction of buildings and engineering works that have already been planned [9]. This study aims to find and describe the main types of “variations” and “claims” in construction projects by looking at the terms of construction contracts [9]. Therefore, the study develops the research objectives:

- identification and characterization of the significant types of “variations” and “claims” in construction projects by the terms of the conditions of construction contracts [9].

- Study the significant causes of the “variations” and “claims” in construction projects.

- Suggest recommendations and proposed solutions to benefit from the study’s results and avoid the causes of “variations” and “claims.”

- Investigate the causes of claims and variations in the MENA region, which recently has a booming construction market with the involvement of international AEC firms with tremendous budgets.

- Extending the investigation to the last decade will be an advantage, as most current research concentrated on COVID-19 after 2019 and neglected other causes that had been started before the pandemic, which may have more significant effects on the construction industry.

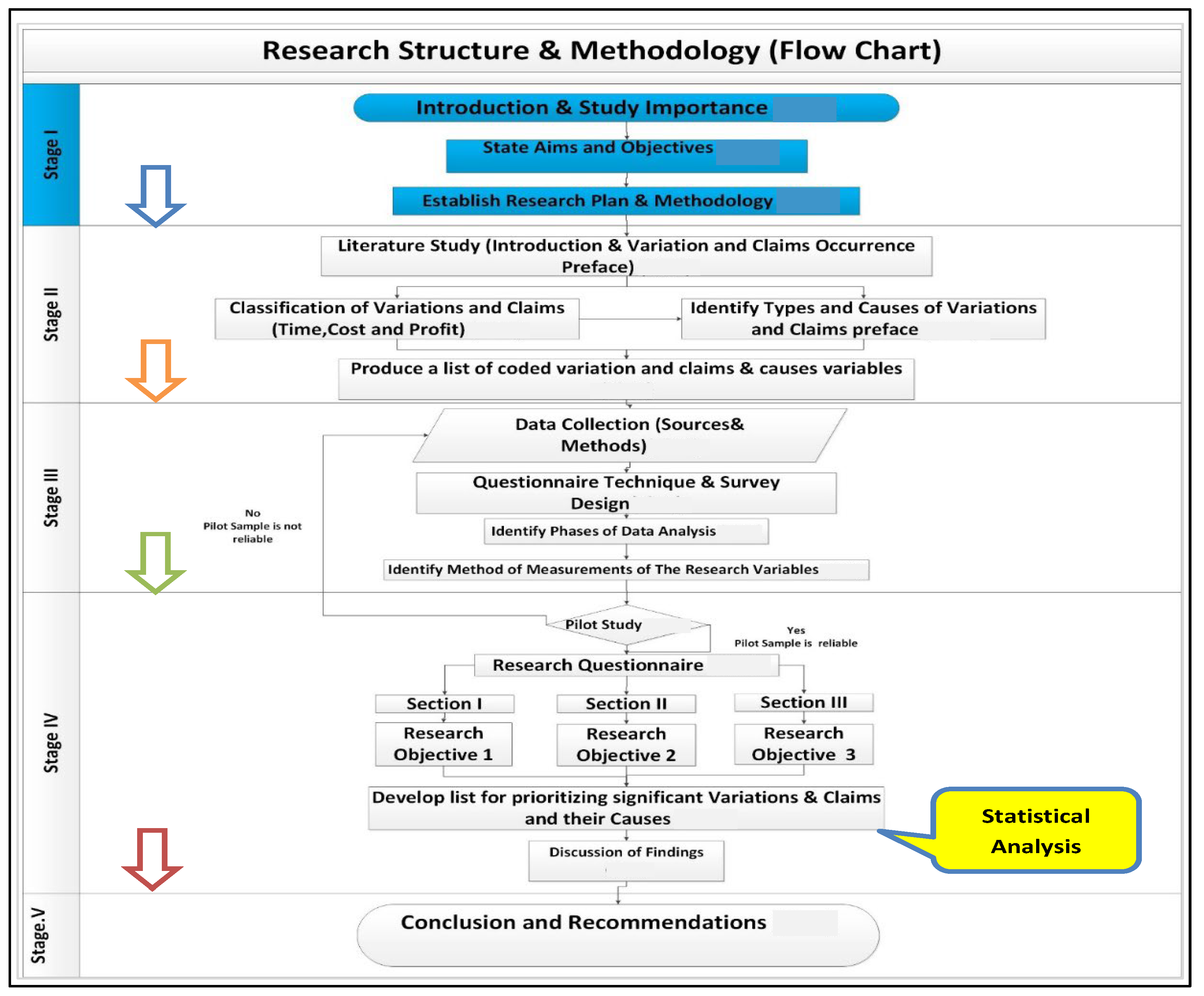

2. Research Methodology

The research methodology adopts a multi-faceted approach, essential for comprehensively addressing the intricacies of Variations and Claims in International Contracts, specifically under FIDIC guidelines. The methodology is structured into distinct but interrelated stages, each contributing uniquely towards achieving our research objectives, as shown in Figure 1.

Scientometric Analysis

In the scientometric analysis phase of this research, a thorough and systematic examination of the existing scholarly literature on variations and claims in international contracts, with a specific focus on those under the Fédération Internationale Des Ingénieurs-Conseils (FIDIC) framework in the MENA region for such period, is carried out. This examination is pivotal for pinpointing the dominant themes, trends, and notable gaps within this academic field. The research delves into a carefully curated collection of academic journals, conference papers, and industry reports using advanced data analysis tools.

To initiate this analysis, Scopus and Web of Science, a database known for its wide array of scientific publications and rapid indexing, was selected as the primary source for data retrieval. This choice enhances the likelihood of accessing relevant and recent literature in this field. In December 2023, a specific search query was employed to gather data. The query, formulated as “(TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Construction” AND “FIDIC” AND “Claim”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Construction” AND “FIDIC” AND “Variation”) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “English”) AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE) OR LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “ar”),” is designed to capture publications that focus on ‘Construction,’ ‘FIDIC,’ along with either ‘Claim’ or ‘Variation.’

Recognizing the enduring significance of ‘construction claims’ as a research topic in the construction sector, the authors decided against setting a time restriction for the publications. Initially, 62 articles are retrieved through this process. Inclusion and exclusion criteria ensure the review’s quality and relevance. Either articles not in English and those not categorized as ‘journal articles’ or ‘conference articles’ were excluded. This refining process narrows down the selection to 49 manuscripts, which are then downloaded and meticulously reviewed.

3. Literature Review

Variations and claims generally arise between the employer and the contractor due to their respective rights and obligations under the contract clauses or due to some events or circumstances.

The FIDIC Conditions of Contract tried to ensure the balanced rights of all parties, even when the employers, engineers, and contractors were exposed to claims, the following sections exhibit classification and causes of variations and claims.

3.1. Classification of Variations and Claims

3.2. Causes of Variations and Claims

3.3. Significance and Avoidability

Significance and avoidability are two critical issues addressed in a real strategy for reducing variations and claims. Avoidability concerns the precautions and preventive procedures that can reduce the consequences of variations and claims. Both are essential in studying the causes of claims and recommended responses.

Avoidability as procedures that reduce the negative impacts of claims and variations can be considered as risk mitigation strategy for construction projects.

4. Results

For deeper analysis, visualization of similarities (VOS), an open-source tool acclaimed for its capability to construct and visualize bibliometric networks, is utilized. This software applies the VOS-viewer technique [10] for this analysis. The process includes examining all keywords in the selected publications, with a predetermined threshold set to include those appearing at least twice. Among 324 keywords, 54 meet this criterion, revealing six main thematic clusters in the analysis, as shown in Figure 2.

These clusters were visually represented in a keyword co-occurrence network, where each cluster is color-coded, and the size of each node (keyword) indicates its frequency of occurrence. The relationships between keywords were depicted through arcs, with the thickness of each line signifying the strength of the relationship. The clusters identified were the yellow cluster representing ‘contractors,’ the red cluster for ‘construction industry and EOT,’ the green cluster signifying ‘construction project management,’ the purple cluster for ‘civil engineering,’ the blue cluster denoting ‘construction and FIDIC,’ and the sky-blue cluster for ‘construction contracts.’ The most prominent keyword, serving as the central node in this network, is ‘construction projects.’

Despite not being constrained by strict keyword thresholds, this visualization highlights a critical observation: previous studies have yet to extensively explore the causes of claims and variations within the context of FIDIC contracts. This gap in the literature underscores the necessity for this research to delve deeply into these aspects, thereby contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of Variations and Claims in construction contracts under FIDIC regulations. There were no similar scholars covering the same period (10 years) in the MENA region in particular.

4.1. Characteristics of the Survey Targeted Participants and Statistical Investigation

The sample size for the survey was determined considering the limited availability of claims & disputes experts. To ensure a statistically representative sample of the population, the following formula was used for the initial calculation:

Sample size.

This calculation is based on:

A confidence level value (z) of 1.96 indicates a 95% confidence level, and an estimated proportion (p) of 0.5 is commonly used when the exact proportion is unknown. A margin of error (ε) set at 0.05 equals 5%.

The initial sample size calculated using this formula was 384. However, a correction was applied to this initial figure due to the finite population of Claims & Disputes experts. The corrected sample size (n) was determined by the following equation, which accounts for the limited population size:

Correction for Limited Sample Population

In this equation, N represents the total population of Claims & Disputes experts. This adjustment resulted in a final sample size of approximately 80. This methodological approach is critical to ensure that the sample size adequately represents the expert population, enhancing the reliability of the survey results.

4.2. Participant Profiles and Group Classifications in the Survey

The survey categorized respondents into six distinct groups, each defined by specific criteria that captured various dimensions of their professional profiles. This categorization facilitated a detailed data analysis, allowing for nuanced insights into industry practices. The groups were as follows:

- PC01—Role of the Respondent (Identity): This classification focused on the professional role of each respondent, identifying their specific position or function within their organization.

- PC02—detailed Managerial Level: Respondents were classified based on their organization’s managerial level, offering insights into the decision-making hierarchy and leadership structure.

- PC03—years of Experience: This category evaluated the individual professional experience of respondents, highlighting the depth and range of their expertise in the industry.

- PC04—organization/Firm’s Experience (Firm’s Number of Years in Business): This group focused on the longevity and historical context of the organizations represented, providing an understanding of the firm’s experience and stability in the industry.

- PC05—Organization/Firm’s Annual Number of Projects: This classification detailed the scale and scope of operations of the respondents’ firms based on the number of projects managed or undertaken annually.

- PC06—Organization/Firm’s Number of Employees: This group provided insights into the organizations’ size and human resource capacity, highlighting the scale of their operations regarding personnel.

4.3. Evaluation of Survey Validity and Reliability

The survey underwent a rigorous evaluation for validity and reliability, focusing on types of variations and claims regarding frequency, impact, and underlying causes. The validity was quantitatively established with a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.97, indicating a high level of internal consistency since this value notably surpasses the commonly accepted threshold of 0.70. Furthermore, the lowest item-total statistic in the survey did not fall below 0.969, reinforcing the validity of the findings. Regarding reliability, the corrected item-total correlation for all dependent and independent survey factors exceeded 0.30.

4.4. Relative Importance Index Test (RII)

The survey incorporated the relative importance index (RII) to analyze participants’ perceptions of various factors. Respondents were requested to assign a rating to each factor, ranging from 1 (‘very rare’) to 5 (‘very high’). Absent responses were not assigned any weight in the RII calculation. This rating system facilitated categorizing responses into five levels of importance: extremely rare (deficient), rare (low), average, high, and very high.

4.5. Assessment of Frequency for Types of Variations and Claims

Respondents from clients, consultants, and contractors were collectively evaluated in assessing the frequency of different variations and claims, as summarized in Table 3. This analysis identified fifty-one distinct types of variations and claims, initially detailed in Table 1. Ten types emerged as the most frequently encountered in projects, consistently reported across all respondent groups. The remaining forty-one types were notably less frequent, indicating a lower occurrence rate in construction projects.

4.6. Assessment of Impact for Types of Variations and Claims

The impact assessment of variations and claims is based on the collective feedback from clients, consultants, and contractors (Table 4). This evaluation aimed to understand the severity of different types of variations and claims as experienced in the industry.

The analysis revealed that 32 variations and claims were frequently identified as significantly impacting construction projects. In contrast, 19 types were perceived to have a less severe impact, suggesting that their occurrence typically results in less disruption or fewer consequences for the projects involved.

4.7. Causes of Variations and Claims (Perceived Agreement Assessment)

Every replying group affirmed the possibility that the majority of the causes listed above could result in claims and variances in construction projects. With varying degrees of agreement, each group concurred that 31 possible causes could lead to these construction variations and claims.

This illustrates the disparities in agreement as each group perceived it. The assessment of the cause by the different responding groups (i.e., clients, consultants, and contractors) was compared using Table 5. The generation of different construction variations and claims can be attributed to these thirty-one proposed causes. However, this bias is not unexpected; others have already noted [11].

4.8. Causes of Variations and Claims (Perceived Significance Assessment)

The responses for the cause’s significant assessment from the viewpoint of all respondents for the first ten categories of variations and claims are shown in Table 6.

4.9. Causes of Variations and Claims (Perceived Avoidability Assessment)

Analysis was done on the responses from the different groups about the avoidability of factors that can lead to or “trigger” the kinds of variations and claims.

5. Discussion

In this study, various statistical analysis methods were pivotal for comprehensively understanding the intricate dynamics of Variations and Claims in FIDIC contracts in the MENA region. Each method contributed uniquely to unraveling different facets of the data, starting with descriptive and inferential statistics. This allowed for establishing a foundational understanding of the data distribution and relationships among variables.

Advancing to more complex analyses like the relative importance index (RII) and Spearman’s correlation obtained more profound insights into the significance and interconnectedness of factors influencing variations and claims.

5.1. Analysis of the Findings (Statistical Hypothesis- Kruskal Wallis Test)

According to the null hypothesis, each population median is equal. A significance threshold 0.05 (represented as α or alpha) is typically adequate. A 5% chance of determining that a difference exists when there is not one is indicated by a significance level of 0.05. P-value < α indicates statistical significance in the discrepancies between some medians. The null hypothesis is true if the p-value is less than or equal to the significance level.

Most of the 6 group respondents to this statistical test said that except T12, which is statistically significant about personal experience (PC03) with a p-value of less than 0.05. The differences between the medians are not statistically significant. As a result, not all group medians are equal, and the null hypothesis was rejected. Furthermore, T14’s relationship to the organization/firm’s experience (PC04) was statistically significant with a p-value of 0.01. The null hypothesis was rejected, indicating that not all item medians are identical, and T16 was also statistically significant about organization/firm’s experience (PC04), with a p-value of =0.009 (lower than 0.05). T39 showed statistical significance about the organization’s or firm’s annual number of projects (PC05) with p-value =0.007. Regarding frequency, it is evident that most variations and claims have no statistically significant disparities between the medians; refer to Appendix B.

5.2. Kruskal Wallis Test (Types of Variations and Claims – Impact)

For this statistical test, most of the group respondents (PC01, PC02, PC03, PC04, PC05, PC06) responded that the differences between the medians are not statistically significant except for the PC01 group we find that T11, T49, T02, T21, T45, T27, T38 and T43 with p-value of 0.002,0.005,0.007,0.035,0.040,0.041,0.042 and 0.049 respectively. In addition, for the Managerial level PC02 group, it was found that T32, T29, T22, and T25 are statistically significant with p-value = 0.026, 0.028, 0.038, and 0.046, respectively. In addition, for the PC03 group, note that only one type, T49, is statistically significant with p-value =0.0.044. For the PC04 group, the T02 and T11 types are statistically significant, with p-values =0.012 and 0.021, respectively. For the PC05 group, the T16 and T39 types are statistically significant, with p-values =0.009 and 0.013, respectively. Finally, the PC06 group has three types, T16, T47, and T26 are statistically significant with p-value =0.032, 0.040, and 0.040.

Most variations and claims in terms of impact have no differences between the group respondents’ medians, which are not statistically significant, as shown in Appendix C.

5.3. Kruskal Wallis Test (Cause of Variations and Claims – Agreement)

For this statistical test, most of the group respondents (PC01, PC02, PC03, PC04, PC05, and PC06) responded that the differences between the medians are not statistically significant except for the PC01 group; it was found that one cause, C31 with a p-value of 0.029. In addition, in the PC02 group, no causes are statistically significant. However, for the PC03 group, note that only one type, C12, C11, C19, C20, C30, C14, and C10, are statistically significant with p-values equals 0.006, 0.009, 0.021, 0.024, 0.026, 0.026, and 0.027 respectively. For PC04 group C04, C06, C08, C10, C14, C07, C12, C29, C11, C17, C20, C25, C13, C28, C24, C03, C27 and C2 are statistically significant with p-value =0.00, 0.00, 0.001, 0.003, 0.005, 0.005, 0.005, 0.010, 0.011, 0.019, 0.021, 0.027, 0.027, 0.039, 0.041, 0.044, 0.048, 0.050 respectively. Too, PC05 group C06, C05, C12, C03, C11, C25, C09, and C29 are statistically significant with p-values =0.002, 0.003, 0.004, 0.011, 0.015, 0.023, 0.025 and 0.042 respectively. Finally, PC06 group C27, C24, C29, C25, C17, C14, C13, C03, C06, C16, C02, C20, C28, C18, C11, C09, C30, C19 are statistically significant with p-value lower than 0.05.

Most of the causes of variations and claims in terms of agreement have no differences between the group respondents’ medians that were not statistically significant, as shown in Appendix D.

5.4. Kruskal Wallis Test (Cause of Variations and Claims – Significance)

Similarly, most of the group respondents (PC01, PC02, PC03, PC04, PC05, PC06) responded that the differences between the medians are not statistically significant except for PC01 group we found that causes C29, C20, C12, C03, C01, C07, C23, C15, C28, C05, C11, C18 and C09 with p-value of 0.001, 0.004, 0.009, 0.011, 0.012, 0.012, 0.019, 0.025, 0.031, 0.0310, 035, 0.037 and 0.046 respectively. In addition, the PC02 group has no statistically significant causes. Although the PC03 group has three types, C04, C10, and C20 are statistically significant with p-values =0.025, 0.039, and 0.043, respectively. Also, The PC04 group has three causes: C04, C11, and C18, which are statistically significant with p-values =0.014, 0.020, and 0.039, respectively. Too, PC05 group C20, C15, C21, C10, C05, C01, C29, C16, and C29 are statistically significant with p-values =0.003, 0.006, 0.009, 0.009, 0.012, 0.013, 0.027, 0.027 and 0.048 respectively. Finally, for PC06 group; C17, C15, C05, C07, C10, C19, C21, C16, C08, C24, C13, C06 and C29 are statistically significant with p-value lower than 0.05.

Most of the causes of variations and claims in terms of significance have no differences between the group respondents’ medians that are not statistically significant (see Appendix E).

5.5. Kruskal Wallis Test (Cause of Variations and Claims – Avoid-Ability)

Similarly, most of the group respondents (PC01, PC02, PC03, PC04, PC05, and PC06) responded that the differences between the medians are not statistically significant except for the PC01 group; it was found that three causes, C06, C08, and C21 with a p-value of 0.011, 0.017 and 0.034 respectively. In addition, the PC02 group has no causes statistically significant. However, the PC03 group has three types, C09, C30, and C10 are statistically significant with p-values =0.010, 0.036, and 0.044, respectively. The PC04 group has three causes; C06, C13, and C02 are statistically significant with p-values =0.020, 0.029, and 0.032, respectively. However, the PC05 group has no statistically significant causes. Finally, the PC06 group has one statistically significant cause, C13, with a p-value lower than 0.05, which = 0.008.

Most causes of variations and claims regarding avoid-ability have no differences between the group respondents’ medians that were not statistically significant (see Appendix F).

5.6. Spearman’s Correlation Test

It is known that the relationship appears in 3 phases; the first phase was (- r < 0), meaning a negative relationship exists between the two variables. The second phase is that (+ r > 0), which means a positive relationship between the two variables. The third phase is (r = 0), meaning there is no relationship between the two variables.

To understand the Spearman correlation coefficient, if the correlation coefficient value (r) = 0, there is no relationship between variables. While the correlation coefficient value (0.0 < r < 0.25) indicated a weak positive relationship. The correlation coefficient value (0.25 ≤ r < 0.75) indicated an average positive relationship. However, there was a strong positive relationship if the correlation coefficient value (0.75 ≤ r < 1). The relationship is entirely positive if the correlation coefficient value equals 1 (r = 1).

Regarding the correlation hypothesis, if r = 0, there is no relation between the two variables and accepting the zero hypothesis (H0), but if r is not equal to 0, there is a relation between the two variables and rejecting the zero hypothesis (H0) and accept the alternative hypothesis (H1). While if sig. > 0.05, accept the zero hypothesis (H0), but if sig. < 0.05 the zero hypothesis (H0) will be refused.

5.6.1. Spearman’s Correlation Test (Types-Frequency) & (Causes-Significance)

It appears that there was a highly positive correlation, denoted by red color, related to the p-value (see Appendix G). Moreover, those denoted by green revealed the correlation between significant causes: C21, C10, C05, and frequent types T16, T23, T38, and T31. While it was lower than 0.05, the H0 hypothesis was not accepted, and the H1 hypothesis was accepted alternatively. Similarly, for significant causes, C15, C16, and C17 correlated with frequented types T16, T23, and T31. Also, a significant cause of C19 is the correlation between frequent types T16, T23, T45, and T31. In addition, the significant cause of C20 correlated with frequent types T16, T23, T38, and T31.

The same is true for significant cause C01, which correlated with frequent types T16, T38, T31, T07, and T09.Finally, significant cause C06 had a correlation relationship with frequent types T16, T23, T38, T31, T34 and T10. For the correlation hypothesis, while the significance is lower than 0.05, reject the H0 zero hypotheses and accept the H1 alternative hypothesis in Appendix G.

5.6.2. Spearman Correlation Test (Types-Impact) & (Causes -Significance)

There appears to be a highly positive correlation for the mentioned correlation coefficient by red color, related to the p-value. The green color reveals that there was a correlation relationship between significant causes C21, C16, C17, C20, and C01 and Impacted types T39, T47, T16, T41, T27, T38, T33, T23, T26, while it is lower than 0.05. Therefore, the H0 was rejected, and the H1 hypothesis was accepted alternatively. Similarly, for significant cause C10 that had a correlation relationship with Impacted types T39, T47, T16, T41, T27, T38, T33 and T26.

In addition, significant causes C05, C15 have a correlation relationship with impacted types T39, T47, T16, T41, T27, T38, T33, T23, T26 and T48. In addition, the significant cause C19 had a correlation relationship with Impacted types T39, T47, T16, T41, T27, T38, T33, T26, and T48.Finally for significant cause C06 has a correlation relationship with Impacted types T39, T47, T16, T41, T27, T38, T33 and T26. For the correlation hypothesis, while the significance was lower than 0.05, we will not accept the H0 zero hypothesis and accept the H1 alternative hypothesis in Appendix H

5.6.3. Spearman Correlation Test (Types-Frequency) & (Causes –Avoid-Ability)

Similarly, there was a highly positive correlation for the mentioned correlation coefficients by red color, related to p-value (significant), which had green color revealing a correlation relationship between avoidable cause C10 and frequent types T23, T38. Also, for avoidable causes, C13 correlated with frequented types T38, T45, and T31. Also, avoidable cause C06 correlated with frequented types T16, T23, T38, and T31. In addition, the avoidable cause C05 correlated with frequented types T16, T31, and T09. Moreover, for avoidable causes, C01, C04, and C09 correlate with frequented type T09. On the other hand, the avoidable cause C05 correlated with frequent types T38 and T09. However, the avoidable cause C02 correlated with frequented types T38, T07, T09, and T10. Meanwhile, the avoidable cause C07 did not correlate with any frequent types.

Finally, the avoidable cause C08 correlated with frequent T38, T09, T45, and T10 types. For the correlation hypothesis, the significance was lower than 0.05 to exclude the H0 zero hypotheses and accept the H1 alternative hypothesis in Appendix I.

5.6.4. Spearman Correlation Test (Types-Impact) & (Causes –Avoid-Ability)

The correlation between the most impacted types and the most avoidable causes was investigated using Spearman’s test (see Appendix J). It appears that there was a highly positive correlation denoted by red color, related to p-value, which has green color reveals that there is a correlation relationship between avoidable cause C10 and impacted types T47, T16, T41, T27 while significant was lower than 0.05, so we will not accept the H0 and accept the H1 alternative hypothesis. For avoidable causes, C13 correlated with impacted types T47, T41, T27, and T38. In addition, avoidable cause C06 had a correlation with impacted types T39, T47, T18, T41, T27, T38, T33 and T26. In addition, avoidable cause C05 had a correlation with impact types T39, T47, T16, T27, T38, T33 and T26.

Moreover, for avoidable causes, C01 and C01 correlated with impacted types T47 and T33.On the other hand, the avoidable cause C24 correlated with impacted types T47, T27, T38, T33, T23, T26, and T48. However, the avoidable cause C02 correlated with impacted types T41, T27, T38, T33 and T26.In contrast, the avoidable causes C04 and C09 do not correlate with any impacted types. Moreover, the avoidable cause C08 had a correlation with impacted types T47, T16, T27, T38, T33, T26 and T48. Finally, the avoidable cause C07 correlated with impacted type T33.

5.7. Overall, the Questionnaire Participant’s Assessment

Respondents were asked to score the questionnaire’s overall coverage in this area and the variables under each section. Additionally, they provided any other remarks on the parts of the variable and any related issues.

Table 8 presents respondents’ responses regarding the types of variations and claims and their significance, where 94.1 % of the clients think that the common types of variations and claims are significant, for the consultants, 88.4 % think that it was significant, and 93.8% for the contractors.

Table 9 presents respondents’ responses regarding the causes of variations and claims and their significance, where 88.2 % of the clients think that the common types of variations and claims are significant, for the consultants, 95.3 % think that it was significant; finally, for the contractors, 93.8 think that it was significant.

Table 10 presents respondents’ responses and questions to help managers predict the significance of types and causes of variations and claims. 94.1 % of the clients think that the survey questions will help managers predict the significance of types and causes of variations and claims; 83.7% of the consultants think that it will help, and 93.8% of the contractors think it will help positively.

The questionnaire responses, shown in Table 11 below, will assist managers in forecasting and suggesting tactics to prevent or lessen variations and claims. Meanwhile, 76.5% of clients believe managers can anticipate and provide ways to prevent or lessen variations and claims. 79% of consultants believe it would be helpful, and eighty-seven percent of contractors believe it will be beneficial.

5.8. K-Means Analysis

This section delves into the K-means clustering algorithm, a pivotal tool in data analytics renowned for its simplicity and efficiency. This method is particularly valuable for the study as it complements the previously discussed Spearman’s Correlation and Kruskal Wallis tests, offering a unique perspective on understanding the dynamics of factors influencing variations and claims in construction contracts. K-means clustering is a widely embraced and substantiated technique in clustering [12].

To determine the appropriate number of clusters (k), various methodologies such as the Hubert statistic, Davies Bouldin index, Dunn index, score function, elbow plot, and silhouette plot have been devised [13]. In this study, the elbow plot method, known for its reliability [14], [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23], was employed for cluster count determination.

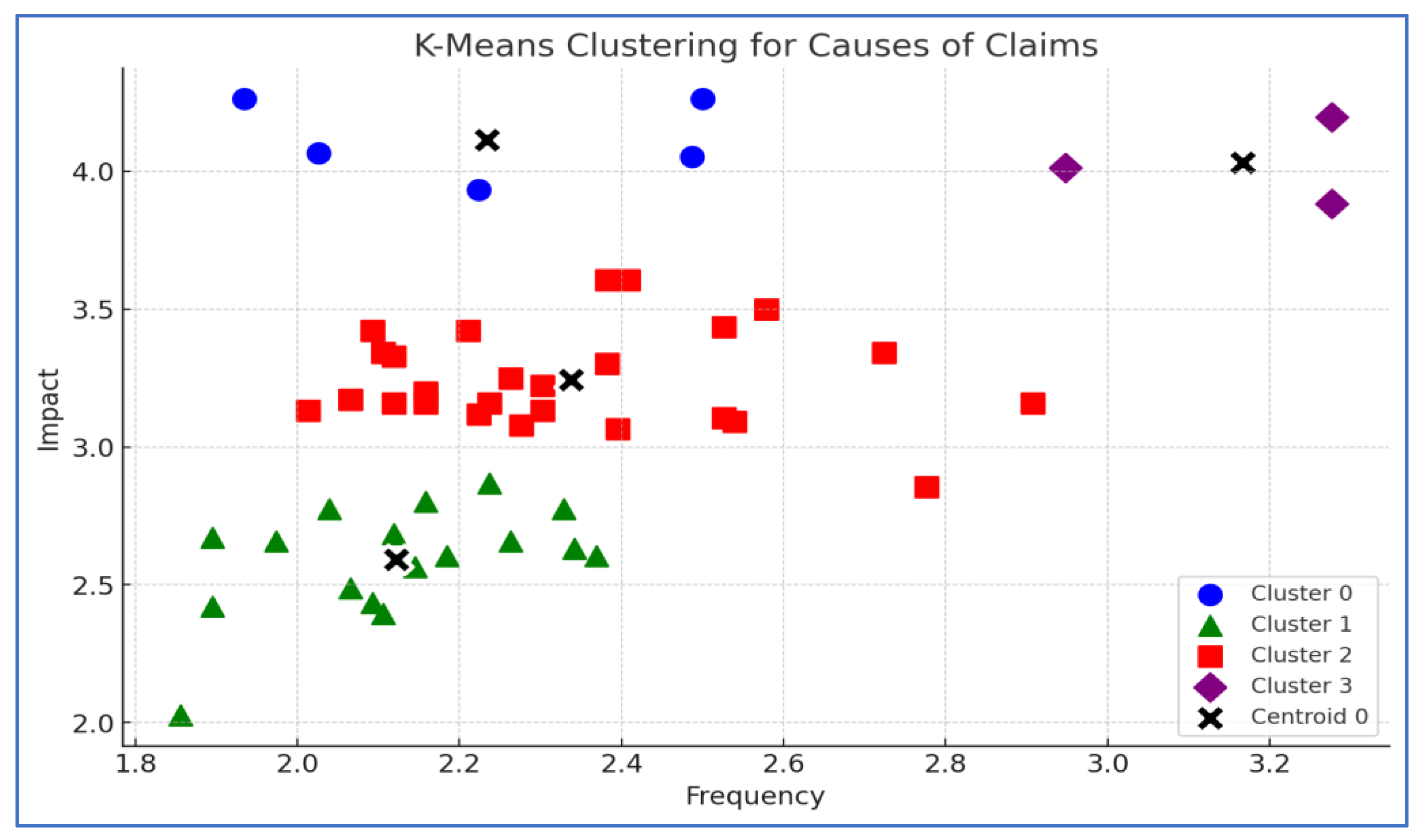

The primary aim of the k-means algorithm is to minimize cluster inertia or the within-cluster sum-of-squares criterion, as delineated by Equation 3, wherein represents samples and stands for the mean of samples within each cluster. The determination of the suitable number of clusters is validated through the elbow plot, displaying distortion scores for a selected number of clusters as per Equation 3. The “elbow” point designates the cluster count at which further additions do not significantly reduce WCSS. Notably, in this analysis, the optimal number of clusters was identified as four, evident in Figure 5.

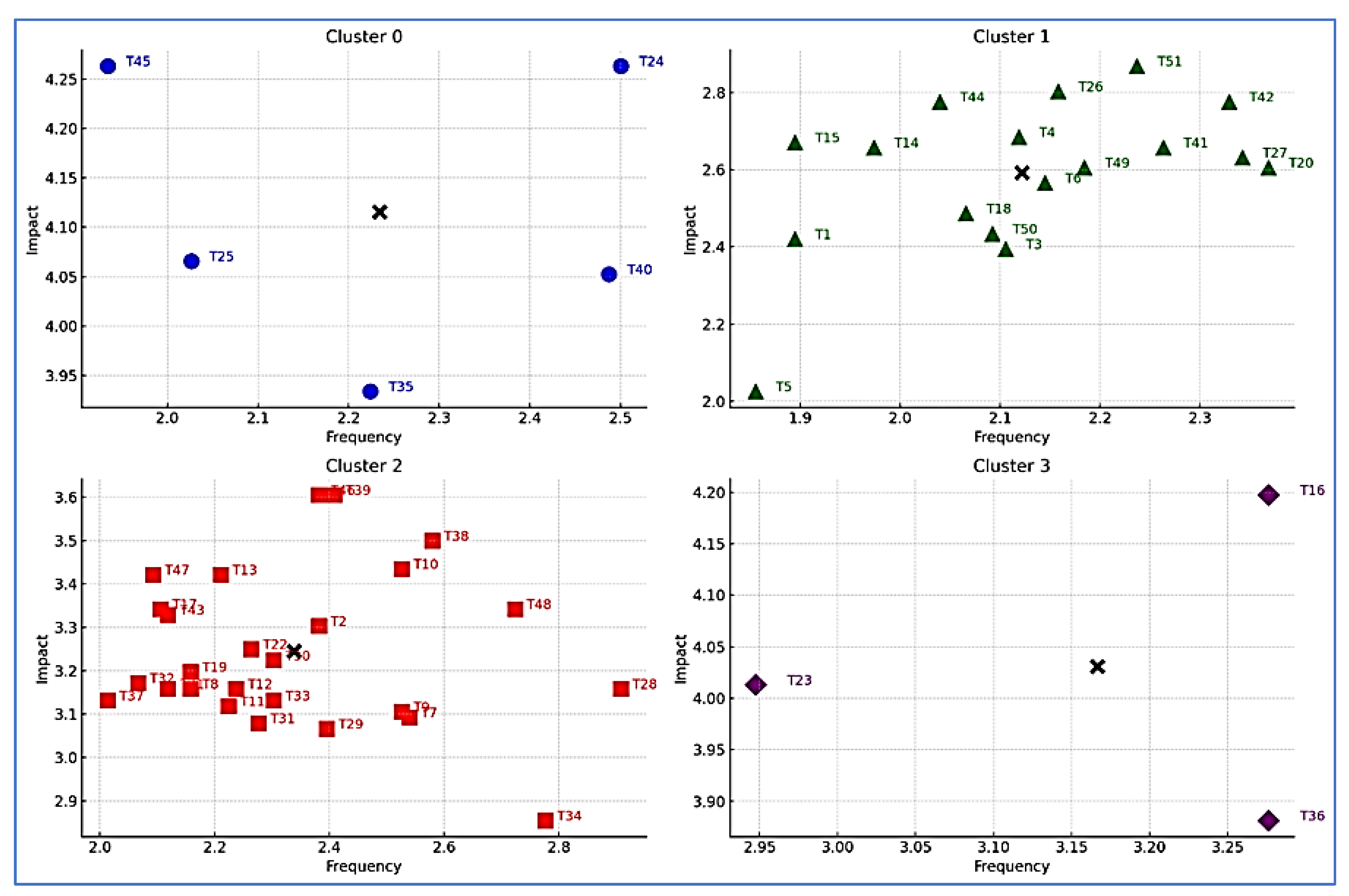

Cluster 0—selective high-impact causes: This cluster includes causes T45, T40, T35, T25, and T24. It is characterized by a significant impact with fewer occurrences and demands focused attention due to its potential substantial effect on projects.

Cluster 1—diverse low-impact causes: With 17 causes (T1, T49, T44, T42, T41, T27, T50, T20, T18, T26, T51, T6, T5, T4, T3, T15, T14), this cluster represents varied and numerous issues of lower individual impact but requiring broad management strategies due to their collective presence.

Cluster 2 - frequent mid-impact causes: The largest cluster with 26 causes (T47, T48, T34, T2, T7, T39, T38, T37, T8, T46, T43, T33, T31, T17, T19, T13, T21, T22, T32, T12, T10, T9, T28, T29, T30, T11), posing a consistent challenge and requiring regular monitoring.

Cluster 3—critical high impact and high-frequency cause: Comprising T23, T36, and T16, these issues are high in impact and frequency, pivotal in the project lifecycle, and necessitating strategic management. Figure 7 visually supports this analysis by showing the network model colored by cluster and detailing the causes of claims within each cluster. Table 12 illustrates these findings, providing a granular view of each cluster’s characteristics.

Figure 6.

K-Means Clustering for Causes of Claims.

Figure 7.

Assigned Causes of Claims for the Four Analyzed K-Means Clusters.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Frequent Types of Variations and Claims

Using the types and causes, RII was applied to construction industry workers in this research. Fifty-one types of variations and claims have been identified in section 1-part two based on a questionnaire survey of 80 respondents. These 51 significant types have been ranked according to respondents’ perceptions, and the top ten are frequent and severe types.

Thus, these types require managerial attention and focus to avoid their frequencies, consequently providing positive benefits in managing construction projects, Table 13.

6.2. Concluding Remarks

Based on the presented results, it is recommended that contract clauses dealing with such issues be given special consideration. The best way to cope with the risk of construction variations and claims is to reduce or avoid them altogether.

Certain fundamental ways and methods can reduce the number of encountered variations and claims (see Appendix A).

6.3. Comparative analysis and correlations summary

The Kruskal-Wallis test in Appendix B shows that project-related issues vary by respondent characteristics. For example, “a failure to rectify defects” has a significant variation based on personal experience (PC03) with a p-value of 0.030, suggesting that people with different experience levels perceive this issue differently. The firm’s experience (PC04) and number of employees (PC06) also significantly affect “termination initiated by the contractor” (p-values of 0.039 and 0.004, respectively). These findings emphasize the importance of personal and organizational experience in addressing frequent project failures and contractor actions. Appendix C examines ways causes affect project outcomes. The Kruskal-Wallis test finds several significant results. For example, “failure to pay the agreed amount due” differs by respondents’ role (PC01) and firm experience (PC04), with p-values of 0.007 and 0.012, respectively. Additionally, “delayed drawings or instructions” significantly affect the firm’s number of projects (PC05) and employees (PC06), with p-values of 0.009 and 0.032. These findings suggest that financial issues and communication delays can significantly affect project performance, highlighting managerial improvement opportunities. The agreement analysis in Appendix D uses the Kruskal-Wallis test to identify significant causes of project issues. “Inadequate design” and “inadequate brief,” with p-values of 0.008 and 0.007, respectively, significantly affect employee numbers (PC06). With a 0.000 p-value, “unclear and inadequate specifications” are significant for the firm’s experience (PC04).

The significance analysis in Appendix E shows how causes affect project outcomes. With p-values of 0.012 and 0.001, “inadequate/inaccurate design” and “inappropriate contract type” affect the firm’s number of projects (PC05) and employees (PC06). With a p-value of 0.002, “inadequate contract administration” negatively impacts project outcomes, particularly employee numbers (PC06). These findings emphasize the importance of accurate design information and contract management for project success and problem mitigation. The Kruskal-Wallis test in Appendix F shows factors related to project issue avoidability. With a p-value of 0.032, “inadequate design” affects the firm’s experience (PC04), suggesting that better design processes could prevent related issues. “Inappropriate contact form” significantly affects respondents (PC01) and personal experience (PC03), with p-values of 0.011 and 0.223.

Appendix G examines variation/claim frequency and cause relationships using Spearman’s correlation. Strong correlations exist between “changes by the client” and “delayed drawings or instructions” (r =.397, p < 0.001) and “inappropriate contractor selection” and “delayed payments” (r =.411, p < 0.001). The interconnectedness of project variations and their causes suggests that addressing root causes could reduce related claims. Appendix H uses Spearman’s correlation to examine variations/claims and their causes. Significant correlations link “changes by the client” to “loss or damage to the works caused by employer’s risks” (r =.447, p < 0.001) and “inappropriate contractor selection” to “client breach of contract” (r =.417, p < 0.001). These findings demonstrate the importance of strategic risk management because specific causes can significantly affect project outcomes. Appendix I examines project issue avoidability and variation/claim correlations. Significant correlations include “inappropriate payment method” and “acceleration of works” (r =.334, p = 0.003) and “inadequate site investigation” and “ambiguous documents” (r =.250, p = 0.029). These correlations suggest better payment methods and site investigations could prevent related project issues. Appendix J compares impactful variations/claims to avoidability causes. Significant correlations exist between “inappropriate contractor selection” and “client’s breach of contract” (r =.307, p = 0.007) and “inadequate contract documentation” and “loss or damage to the works caused by employer’s risks” (r =.310, p).

In conclusion, Kruskal-Wallis’s test and Spearman’s correlation analysis across appendices reveal how respondent roles, personal and organizational experience, and project causes affect project variation and claim frequency, impact, agreement, and avoidability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Ahmed Mohammed Abdelalim; Data curation, Ahmed Mohammed Abdelalim, Mohamed Tantawy and Mohamed Ezz Al Regal; Formal analysis, Ahmed Mohammed Abdelalim and Mohamed Ezz Al Regal; Funding acquisition, Ahmed Mohammed Abdelalim, Ruqaya Al-Sabah and Salah Omar Said; Investigation, Ahmed Mohammed Abdelalim, Mohamed Salem, Mohamed Tantawy and Mohamed Ezz Al Regal; Methodology, Ahmed Mohammed Abdelalim; Project administration, Ahmed Mohammed Abdelalim; Resources, Ahmed Mohammed Abdelalim; Software, Ahmed Mohammed Abdelalim, Mohamed Tantawy and Mohamed Ezz Al Regal; Supervision, Ahmed Mohammed Abdelalim; Validation, Ahmed Mohammed Abdelalim, Mohamed Salem, Ruqaya Al-Sabah, Salah Omar Said, Mohamed Tantawy and Mohamed Ezz Al Regal; Visualization, Ahmed Mohammed Abdelalim, Mohamed Salem, Ruqaya Al-Sabah, Salah Omar Said, Mohamed Tantawy and Mohamed Ezz Al Regal; Writing – original draft, Ahmed Mohammed Abdelalim and Mohamed Ezz Al Regal; Writing – review & editing, Ahmed Mohammed Abdelalim, Mohamed Salem, Ruqaya Al-Sabah, Salah Omar Said and Mohamed Tantawy. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

There is no available funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Guidelines & Techniques to Control Significant and Avoidable Causes of Claims and Variations

| # | Avoidable Causes of Variations and Claims | Recommended Mitigation/ Response Strategy |

| 1 | Changes by Client (C21) |

|

| 2 | Inappropriate Contractor Selection (C10) |

|

| 3 |

Contract Type/ Strategy - C05 |

|

| 4 |

Inappropriate/ Unexpected Time Control (Target)-(C15) |

|

| 5 |

Inappropriate/ Unexpected Cost Control (Target)- C16 |

|

| 6 |

Lack of Information for Decision-Making; Decisiveness-(C19) |

|

| 7 |

Inappropriate /Unexpected Quality Control (Target)-(C17) |

|

| 8 | Slow Client Response- (C20) |

|

| 9 |

Inadequate/ Inaccurate Design Information- (C01) |

|

| 10 | Inappropriate Contract Form- (C06) |

|

| 11 | Inappropriate Payment Method- (C13) |

|

| 12 | Inadequate Site Investigations- (C24) |

|

| 13 | Unclear & Inadequate Specifications- (C04) |

|

| 14 | Inadequate Design Documentation- (C02) |

|

| 15 |

Inadequate Contract Documentation- (C08) |

|

| 16 | Inadequate Contract Administration-(C07) |

|

| 17 |

Incomplete Tender Information- (C09) |

|

Appendix B. Kruskal Wallis test and p-value (Types of variations and claims – in terms of Frequency)

| Code | Type | Role of the Respondents (PC01) | Managerial Level (PC02) | Personal Experience (PC03) |

Organization/ Firm’s Experience (Years) (PC04) |

Organization/ Firm’s Annual Number of Projects (PC05) | Organization/ Firm’s Number of Employees (PC06) | |||||||

|

Kruskal- Wallis H |

(P-Value) |

Kruskal- Wallis H |

(P-Value) |

Kruskal- Wallis H |

(P-Value) |

Kruskal- Wallis H |

(P-Value) |

Kruskal- Wallis H |

(P-Value) |

Kruskal- Wallis H |

(P-Value) | |||

| T12 | A failure to rectify defects | 3.757 | 0.153 | 0.880 | 0.644 | 10.716 | 0.030 | .0.27 | 0.866 | 1.495 | 0.828 | 1.233 | 0.873 | |

| T14 | Contractor’s failure to insure | 0.389 | 0.823 | 1.935 | 0.380 | 4.351 | 0.361 | 12.058 | 0.017 | 6.596 | 0.159 | 2.853 | 0.583 | |

| T16 | Delayed drawings or instructions | 0.741 | 0.690 | 2.696 | 0.260 | 1.402 | 0.844 | 13.614 | 0.009 | 6.451 | 0.168 | 1.103 | 0.894 | |

| T36 | Termination initiated by the contractor | 5.676 | 0.059 | 2.776 | 0.250 | 3.372 | 0.498 | 10.077 | 0.039 | 2.345 | 0.673 | 15.413 | 0.004 | |

| T39 | Loss or damage to the works caused Employer’s Risks | 1.232 | 0.540 | 0.949 | 0.622 | 6.340 | 0.175 | 7.578 | 0.108 | 14.220 | 0.007 | 6.147 | 0.188 | |

Appendix C. Kruskal Wallis test and p-value (Types of variations and claims – in terms of Impact)

| Code | Type | Role of the Respondents (PC01) | Managerial Level (PC02) | Personal Experience (PC03) | Firm’s Experiencein business) (PC04) | Firm’s Annual Number of Projects (PC05) | Firm’s Number of Employees (PC06) | |||||||

| Kruskal-Wallis H | (P-Value) | Kruskal-Wallis H | (P-Value) | Kruskal-Wallis H | (P-Value) | Kruskal-Wallis H | (P-Value) | Kruskal-Wallis H | (P-Value) | Kruskal-Wallis H | (P-Value) | |||

| T02 | Failure to pay agreed amount due. | 9.810 | 0.007 | 0.853 | 0.653 | 5.711 | 0.222 | 12.868 | 0.012 | 1.668 | 0.797 | 0.941 | 0.919 | |

| T11 | Failed tests on completions | 12.143 | 0.002 | 0.980 | 0.613 | 1.286 | 0.864 | 11.567 | 0.021 | 4.106 | 0.392 | 1.291 | 0.863 | |

| T16 | Delayed drawings or instructions | 4.236 | 0.120 | 1.286 | 0.526 | 6.177 | 0.186 | 5.823 | 0.213 | 13.615 | 0.009 | 10.538 | 0.032 | |

| T21 | Fossils, archaeological or geological | 6.722 | 0.035 | 0.806 | 0.668 | 0.793 | 0.939 | 7.127 | 0.129 | 1.836 | 0.766 | 4.559 | 0.336 | |

| T22 | Additional tests by the engineer | 4.437 | 0.109 | 6.532 | 0.038 | 4.671 | 0.323 | 1.841 | 0.765 | 3.470 | 0.482 | 1.201 | 0.878 | |

| T25 | Shortage of personnel or goods | 4.334 | 0.115 | 6.174 | 0.046 | 6.841 | 0.145 | 2.121 | 0.713 | 2.726 | 0.605 | 1.870 | 0.760 | |

| T26 | Employer’s delay or impediment | 2.120 | 0.346 | 4.185 | 0.123 | 0.414 | 0.981 | 1.632 | 0.803 | 2.038 | 0.729 | 10.035 | 0.040 | |

| T27 | Delays caused by authorities | 6.376 | 0.041 | 1.003 | 0.606 | 1.882 | 0.757 | 4.640 | 0.326 | 11.746 | 0.019 | 5.343 | 0.254 | |

| T29 | Employer using works partially | 0.105 | 0.949 | 7.149 | 0.028 | 3.864 | 0.425 | 4.435 | 0.350 | 5.405 | 0.248 | 2.994 | 0.559 | |

| T32 | Adopt value engineering proposal | 2.326 | 0.312 | 7.327 | 0.026 | 0.248 | 0.993 | 2.123 | 0.713 | 3.247 | 0.517 | 0.491 | 0.974 | |

| T38 | Ambiguity in Documents | 6.357 | 0.042 | 0.663 | 0.718 | 2.917 | 0.572 | 1.028 | 0.906 | 0.964 | 0.915 | 4.404 | 0.354 | |

| T39 | Loss or damage to the works caused Employer’s Risks | 3.103 | 0.212 | 2.344 | 0.310 | 5.551 | 0.235 | 3.117 | 0.538 | 12.596 | 0.013 | 9.185 | 0.057 | |

| T43 | Refusal of contractor objection to nomination | 6.020 | 0.049 | 2.210 | 0.331 | 6.101 | 0.192 | 3.929 | 0.416 | 2.498 | 0.645 | 1.374 | 0.849 | |

| T45 | Acceleration of Works | 6.446 | 0.040 | 1.929 | 0.381 | 7.492 | 0.112 | 4.239 | 0.375 | 3.131 | 0.536 | 2.153 | 0.708 | |

| T47 | Client’s Breach of Contract | 4.435 | 0.109 | 0.294 | 0.863 | 1.745 | 0.783 | 5.417 | 0.247 | 8.780 | 0.067 | 10.051 | 0.040 | |

| T49 | Currency Fluctuation | 10.413 | 0.005 | 2.801 | 0.246 | 9.776 | 0.044 | 6.154 | 0.188 | 2.455 | 0.653 | 3.481 | 0.481 | |

Appendix D. Kruskal Wallis test and p-value (Types of variations and claims – in terms of agreement)

| Code | Cause | Role of the Respondents (PC01) | Managerial Level (PC02) | Personal Experience (PC03) | Organization/ Firm’s Experience (PC04) | Organization/ Firm’s Annual Number of Projects (PC05) | Organization/ Firm’s Number of Employees (PC06) | ||||||

| Kruskal-Wallis H | .(P-Value) | Kruskal-Wallis H | (P-Value) | Kruskal-Wallis H | (P-Value) | Kruskal-Wallis H | .(P-Value) | Kruskal-Wallis H | .(P-Value) | Kruskal-Wallis H | .(P-Value) | ||

| C02 | Inadequate Design. | 1.221 | 0.543 | 2.181 | 0.336 | 5.071 | 0.280 | 4.855 | 0.303 | 6.433 | 0.169 | 13.818 | 0.008 |

| C03 | Inadequate Brief | 0.997 | 0.608 | 0.045 | 0.978 | 4.924 | 0.295 | 9.823 | 0.044 | 12.967 | 0.011 | 14.055 | 0.007 |

| C04 | Unclear & Inadequate Specs. | 4.941 | 0.085 | 1.826 | 0.401 | 2.462 | 0.651 | 21.749 | 0.000 | 5.655 | 0.226 | 5.367 | 0.252 |

| C05 | Inappropriate Contract Type | 2.773 | 0.250 | 1.178 | 0.555 | 7.109 | 0.130 | 7.520 | 0.111 | 16.349 | 0.003 | 4.917 | 0.296 |

| C06 | Inappropriate Contract Form | 2.015 | 0.365 | 2.237 | 0.327 | 6.817 | 0.146 | 20.442 | 0.000 | 17.144 | 0.002 | 14.043 | 0.007 |

| C07 | Inadequate Contract Administration | 5.267 | 0.072 | 1.334 | 0.513 | 2.020 | 0.732 | 14.674 | 0.005 | 4.553 | 0.336 | 0.854 | 0.931 |

| C08 | Inadequate Contract Documents | 2.433 | 0.296 | 2.508 | 0.285 | 8.510 | 0.075 | 18.180 | 0.001 | 8.729 | 0.068 | 9.314 | 0.054 |

| C09 | Incomplete Tender Information | 1.577 | 0.455 | 0.046 | 0.977 | 5.389 | 0.250 | 6.898 | 0.141 | 11.187 | 0.025 | 11.288 | 0.024 |

| C10 | Inappropriate Contractor Selection | 2.707 | 0.258 | 3.805 | 0.149 | 10.949 | 0.027 | 15.995 | 0.003 | 7.654 | 0.105 | 6.037 | 0.196 |

| C11 | Unrealistic Tender Pricing | 2.557 | 0.278 | 3.768 | 0.152 | 13.541 | 0.009 | 13.012 | 0.011 | 12.290 | 0.015 | 11.334 | 0.023 |

| C12 | Unrealistic Client Expectations | 3.224 | 0.199 | 2.811 | 0.245 | 14.404 | 0.006 | 14.668 | 0.005 | 15.187 | 0.004 | 7.866 | 0.097 |

| C13 | Inappropriate Payment Method | 4.218 | 0.121 | 1.526 | 0.466 | 6.919 | 0.140 | 10.975 | 0.027 | 9.080 | 0.059 | 16.076 | 0.003 |

| C14 | Inappropriate Document Control | 2.581 | 0.275 | 1.700 | 0.427 | 11.051 | 0.026 | 15.091 | 0.005 | 7.038 | 0.134 | 16.094 | 0.003 |

| C16 | Inappropriate/ Unexpected Cost Control (Target) | 2.024 | 0.364 | 1.731 | 0.421 | 7.469 | 0.113 | 5.733 | 0.220 | 5.949 | 0.203 | 13.823 | 0.008 |

| C17 | Inappropriate/ Unexpected Quality Control (Target) | 4.758 | 0.093 | 0.106 | 0.948 | 8.535 | 0.074 | 11.844 | 0.019 | 9.188 | 0.057 | 19.021 | 0.001 |

| C18 | Poor Communications | 3.506 | 0.173 | 0.358 | 0.836 | 6.813 | 0.146 | 4.159 | 0.385 | 2.665 | 0.615 | 13.069 | 0.011 |

| C19 | Lack of (Decisiveness) | 1.221 | 0.543 | 0.804 | 0.669 | 11.500 | 0.021 | 7.138 | 0.129 | 7.686 | 0.104 | 10.905 | 0.028 |

| C20 | Slow Client Response | 3.472 | 0.176 | 4.648 | 0.098 | 11.252 | 0.024 | 11.589 | 0.021 | 8.602 | 0.072 | 13.742 | 0.008 |

| C21 | Changes by Client | 3.959 | 0.138 | 1.537 | 0.464 | 6.285 | 0.179 | 9.489 | 0.050 | 5.426 | 0.246 | 4.777 | 0.311 |

| C24 | Inadequate Site Investigations | 0.464 | 0.793 | 0.011 | 0.995 | 6.324 | 0.176 | 9.965 | 0.041 | 7.853 | 0.097 | 23.056 | 0.000 |

| C25 | Unrealistic Expectations ( By the Contractor) | 2.574 | 0.276 | 0.726 | 0.696 | 6.848 | 0.144 | 10.994 | 0.027 | 11.313 | 0.023 | 19.155 | 0.001 |

| C27 | Personality Clashes of Participants | 2.463 | 0.292 | 0.866 | 0.648 | 5.909 | 0.206 | 9.581 | 0.048 | 9.259 | 0.055 | 25.707 | 0.000 |

| C28 | Poor Management By Participants | 0.738 | 0.692 | 0.047 | 0.977 | 8.442 | 0.077 | 10.064 | 0.039 | 5.525 | 0.238 | 13.343 | 0.010 |

| C29 | Adversarial Cultural Affairs | 2.141 | 0.343 | 0.640 | 0.726 | 6.980 | 0.137 | 13.252 | 0.010 | 9.925 | 0.042 | 19.660 | 0.001 |

| C30 | Uncontrollable External Events | 1.213 | 0.545 | 0.857 | 0.651 | 11.095 | 0.026 | 7.143 | 0.129 | 3.248 | 0.517 | 10.913 | 0.028 |

| C31 | Exaggerated Claims | 7.108 | 0.029 | 1.228 | 0.541 | 7.047 | 0.133 | 7.527 | 0.111 | 7.732 | 0.102 | 4.664 | 0.324 |

Appendix E. Kruskal Wallis test and p-value (Types of variations and claims – in terms of significance)

| Code | Cause | Role of the Respondents (PC01) | Managerial Level (PC02) | Personal Experience (PC03) | Organization/ Firm’s Experience (Firm’s Number of Years) (PC04) | Organization/ Firm’s Annual Number of Projects (PC05) | Organization/ Firm’s Number of Employees (PC06) | |||||||

| Kruskal-Wallis H | P-Value | Kruskal-Wallis H | P-Value | Kruskal-Wallis H | P-Value | Kruskal-Wallis H | P-Value | Kruskal-Wallis H | P-Value | Kruskal-Wallis H | P-Value | |||

| C01 | Inadequate/ Inaccurate Design | 8.92 | 0.012 | 0.372 | 0.830 | 2.069 | 0.723 | 4.038 | 0.401 | 12.699 | 0.013 | 8.493 | 0.075 | |

| C03 | Inadequate Brief | 9.09 | 0.01 | 1.894 | 0.388 | 7.387 | 0.117 | 7.114 | 0.130 | 3.263 | 0.515 | 6.746 | 0.150 | |

| C04 | Unclear & Inadequate Specifications | 5.04 | 0.080 | 2.802 | 0.246 | 11.111 | 0.025 | 12.551 | 0.014 | 6.064 | 0.194 | 7.515 | 0.111 | |

| C05 | Inappropriate Contract Type | 6.95 | 0.031 | 0.702 | 0.704 | 7.852 | 0.097 | 7.395 | 0.116 | 12.882 | 0.012 | 18.944 | 0.001 | |

| C06 | Inappropriate Contract Form | 3.002 | 0.223 | 2.110 | 0.348 | 5.036 | 0.284 | 3.565 | 0.468 | 9.563 | 0.048 | 11.976 | 0.018 | |

| C07 | Inadequate Contract Administration | 8.91 | 0.012 | 0.579 | 0.749 | 3.059 | 0.548 | 4.436 | 0.350 | 7.796 | 0.099 | 17.400 | 0.002 | |

| C08 | Inadequate Contract Docs. | 1.83 | 0.400 | 2.267 | 0.322 | 4.009 | 0.405 | 4.619 | 0.329 | 4.800 | 0.308 | 12.948 | 0.012 | |

| C09 | Incomplete Tender Information | 6.14 | 0.046 | 2.411 | 0.300 | 6.970 | 0.138 | 7.981 | 0.092 | 3.713 | 0.446 | 4.670 | 0.323 | |

| C10 | Inappropriate Contractor Selection | 2.00 | 0.367 | 2.025 | 0.363 | 10.113 | 0.039 | 8.103 | 0.088 | 13.516 | 0.009 | 16.415 | 0.003 | |

| C11 | Unrealistic Tender Pricing | 6.71 | 0.035 | 0.233 | 0.890 | 8.069 | 0.089 | 11.710 | 0.020 | 2.540 | 0.637 | 8.474 | 0.076 | |

| C12 | Unrealistic Client Expectations | 9.49 | 0.009 | 1.183 | 0.554 | 1.880 | 0.758 | 5.153 | 0.272 | 5.957 | 0.202 | 9.015 | 0.061 | |

| C13 | Inappropriate Payment Method | 4.63 | 0.099 | 0.846 | 0.655 | 3.483 | 0.480 | 2.253 | 0.689 | 7.175 | 0.127 | 12.042 | 0.017 | |

| C14 | Inappropriate Document Control | 1.72 | 0.421 | 0.108 | 0.947 | 4.141 | 0.387 | 1.238 | 0.872 | 5.515 | 0.238 | 4.552 | 0.336 | |

| C15 | Inappropriate/ Unexpected Time Control (Target) | 7.34 | 0.025 | 0.011 | 0.995 | 7.869 | 0.096 | 7.247 | 0.123 | 14.352 | 0.006 | 21.28 | 0.000 | |

| C16 | Inappropriate/ Unexpected Cost Control (Target) | 4.14 | 0.126 | 1.456 | 0.483 | 5.846 | 0.211 | 5.821 | 0.213 | 10.956 | 0.027 | 13.44 | 0.009 | |

| C17 | Inappropriate/ Unexpected Quality Control (Target) | 4.85 | 0.088 | 2.925 | 0.232 | 5.286 | 0.259 | 7.227 | 0.124 | 7.661 | 0.105 | 21.705 | 0.000 | |

| C18 | Poor Communications | 6.59 | 0.037 | 1.379 | 0.502 | 3.132 | 0.536 | 10.064 | 0.039 | 3.327 | 0.505 | 2.739 | 0.602 | |

| C19 | Lack of Decisiveness | 4.63 | 0.099 | 2.345 | 0.310 | 3.896 | 0.420 | 4.594 | 0.332 | 8.482 | 0.075 | 15.25 | 0.004 | |

| C20 | Slow Client Response | 10.96 | 0.004 | 0.819 | 0.664 | 9.864 | 0.043 | 4.353 | 0.360 | 16.149 | 0.003 | 6.914 | 0.140 | |

| C21 | Changes by Client | 4.271 | 0.118 | 1.245 | 0.536 | 6.882 | 0.142 | 7.331 | 0.119 | 13.584 | 0.009 | 15.214 | 0.004 | |

| C23 | Poor Workmanship | 7.948 | 0.019 | 0.668 | 0.716 | 3.692 | 0.449 | 7.843 | 0.098 | 4.764 | 0.312 | 1.142 | 0.888 | |

| C24 | Inadequate Site Investigation | 0.837 | 0.658 | 0.320 | 0.852 | 1.904 | 0.753 | 8.113 | 0.088 | 5.419 | 0.247 | 12.387 | 0.015 | |

| C28 | Poor Management | 6.953 | 0.031 | 0.240 | 0.887 | 8.590 | 0.072 | 3.515 | 0.476 | 2.022 | 0.732 | 6.483 | 0.166 | |

| C29 | Adversarial Cultural Affairs | 15.06 | 0.001 | 0.075 | 0.963 | 4.051 | 0.399 | 7.528 | 0.110 | 10.968 | 0.027 | 10.025 | 0.040 | |

Appendix F. Kruskal Wallis test and p-value (Types of variations and claims – in terms of avoid ability)

| Code | Cause | Role of the Respondents (PC01) | Managerial Level (PC02) | Personal Experience (PC03) | Organization/ Firm’s Experience (Firm’s Number of Years) (PC04) | Organization/ Firm’s Annual Number of Projects (PC05) | Organization/ Firm’s Number of Employees (PC06) | |||||||||

| Kruskal-Wallis H | (P-Value) | Kruskal-Wallis H | (P-Value) | Kruskal-Wallis H | (P-Value) | Kruskal-Wallis H | (P-Value) | Kruskal-Wallis H | (P-Value) | Kruskal-Wallis H | (P-Value) | |||||

| C02 | Inadequate Design | 0.336 | 0.845 | 0.989 | 0.610 | 3.995 | 0.407 | 10.590 | 0.032 | 9.109 | 0.058 | 2.490 | 0.646 | |||

| C06 | Inappropriate Contract Form | 9.055 | 0.011 | 5.086 | 0.079 | 5.691 | 0.223 | 11.693 | 0.020 | 6.923 | 0.140 | 6.264 | 0.180 | |||

| C08 | Inadequate Contract Documents | 8.158 | 0.017 | 1.232 | 0.540 | 3.889 | 0.421 | 1.588 | 0.811 | 2.193 | 0.700 | 5.175 | 0.270 | |||

| C09 | Incomplete Tender Information | 2.093 | 0.351 | 2.717 | 0.257 | 13.175 | 0.010 | 4.111 | 0.391 | 1.753 | 0.781 | 2.316 | 0.678 | |||

| C10 | Inappropriate Contractor Selection | 2.769 | 0.250 | 2.121 | 0.346 | 9.798 | 0.044 | 1.463 | 0.833 | 3.212 | 0.523 | 2.881 | 0.578 | |||

| C13 | Inappropriate Payment Method | 1.031 | 0.597 | 0.153 | 0.927 | 5.576 | 0.233 | 10.797 | 0.029 | 7.427 | 0.115 | 13.673 | 0.008 | |||

| C21 | Changes by Client | 6.743 | 0.034 | 4.693 | 0.096 | 1.210 | 0.876 | 1.191 | 0.880 | 2.101 | 0.717 | 5.204 | 0.267 | |||

| C30 | Uncontrollable External Events | 0.378 | 0.828 | 1.468 | 0.480 | 10.300 | 0.036 | 2.847 | 0.584 | 2.727 | 0.604 | 3.585 | 0.465 | |||

Appendix G. Spearman coefficients and p-values between the most frequented: types of variations/claims and causes

| TYPE (Frequency) | T16 | T23 | T38 | T45 | T31 | T34 | T25 | T07 | T09 | T10 | ||

| CAUSE (SIGNIFICANCE) | Correlation (Coefficients) | Delayed drawings or instructions | A variation or significant change to the quantities | Ambiguity in Documents | Acceleration of Works | An omission of work forming | Delayed payments | Shortage of personnel or goods | Rejection of defective plant and / or materials | Revised methods of working due to slow progress | Delay damages | |

| C21 | Changes by Client | Correlation | .397** | .242* | .280* | .148 | .366** | .046 | .033 | .054 | -.025 | .114 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | .035 | .014 | .202 | .001 | .694 | .780 | .644 | .830 | .325 | ||

| C10 | Significance Inappropriate Contractor Selection | Correlation | .346** | .279* | .236* | .126 | .411** | .018 | .070 | -.002 | -.005 | .179 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .002 | .015 | .041 | .277 | .000 | .880 | .546 | .984 | .969 | .122 | ||

| C05 | Significance Inappropriate Contract Type (Strategy) | Correlation | .291* | .328** | .251* | .102 | .460** | .034 | -.038 | .066 | .049 | .140 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .011 | .004 | .028 | .382 | .000 | .768 | .742 | .574 | .674 | .227 | ||

| C15 | Significance Inappropriate/ Unexpected Time Control | Correlation | .229* | .258* | .146 | .135 | .320** | .037 | -.005 | .140 | .093 | .187 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .046 | .025 | .209 | .244 | .005 | .748 | .968 | .229 | .423 | .106 | ||

| C16 | Significance Inappropriate/ Unexpected Cost Control | Correlation | .268* | .306** | .133 | .220 | .426** | .157 | .084 | .200 | .204 | .240* |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .019 | .007 | .253 | .056 | .000 | .175 | .472 | .083 | .078 | .037 | ||

| C19 | Significance Lack of Decisiveness | Correlation | .320** | .333** | .179 | .266* | .426** | .019 | -.036 | .125 | .147 | .119 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .005 | .003 | .123 | .020 | .000 | .868 | .760 | .281 | .206 | .306 | ||

| C17 | Significance Inappropriate/ Unexpected QC (Target) | Correlation | .304** | .250* | .142 | .077 | .297** | .021 | -.085 | .051 | .039 | .096 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .008 | .029 | .223 | .507 | .009 | .855 | .463 | .662 | .736 | .408 | ||

| C20 | Significance Slow Client Response | Correlation | .389** | .321** | .334** | .099 | .457** | .211 | .132 | .142 | -.016 | .196 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .001 | .005 | .003 | .393 | .000 | .067 | .256 | .222 | .890 | .089 | ||

| C01 | Significance Inadequate/ Inaccurate Design Information | Correlation | .297** | .192 | .237* | .062 | .317** | .177 | .168 | .236* | .240* | .207 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .009 | .096 | .039 | .595 | .005 | .127 | .146 | .040 | .037 | .073 | ||

| C06 | Significance Inappropriate Contract Form | Correlation | .263* | .291* | .265* | .197 | .440** | .259* | .004 | -.015 | -.025 | .246* |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .022 | .011 | .021 | .088 | .000 | .024 | .975 | .897 | .827 | .032 | ||

Appendix H. Spearman coefficients and p-value between frequented: Types of variations/claims and causes.

| TYPE (Impact) | T39 | T47 | T16 | T41 | T27 | T38 | T33 | T23 | T26 | T48 | ||

| CAUSE (SIGNIFICANCE) | Correlation (Coefficients) | Loss or damage to the works caused Employer’s Risks | Client’s Breach of Contract | Delayed drawings or instructions | Force Majeure | Delays caused by authorities | Ambiguity in Documents | Changes in legislation | A variation or change of quantities | Employer’s delay or impediment |

Inflation / Price Escalation |

|

| C21 | Changes by Client | Correlation | .447** | .424** | .470** | .389** | .548** | .468** | .529** | .252* | .392** | .136 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | 0.000 | .000 | .001 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .028 | .000 | .240 | ||

| C10 | Inappropriate Contractor Selection | Correlation | .559** | .417** | .385** | .462** | .595** | .490** | .432** | .174 | .479** | .189 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | .000 | .001 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .133 | .000 | .102 | ||

| C05 | Inappropriate Contract Type | Correlation | .501** | .481** | .433** | .438** | .560** | .507** | .542** | .295** | .457** | .276* |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .010 | .000 | .016 | ||

| C15 | Inappropriate/ Unexpected Time Control | Correlation | .461** | .492** | .487** | .398** | .581** | .391** | .410** | .256* | .383** | .313** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .026 | .001 | .006 | ||

| C16 | Inappropriate/ Unexpected Cost Control | Correlation | .438** | .453** | .453** | .390** | .539** | .469** | .519** | .345** | .357** | .136 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .002 | .002 | .243 | ||

| C19 | Lack of Information for (Decisiveness) | Correlation | .556** | .561** | .377** | .309** | .538** | .448** | .486** | .207 | .462** | .336** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | .000 | .001 | .007 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .073 | .000 | .003 | ||

| C17 | Inappropriate/ Unexpected QC | Correlation | .447** | .413** | .489** | .412** | .455** | .457** | .474** | .287* | .404** | .098 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .012 | .000 | .402 | ||

| C20 | Slow Client Response | Correlation | .360** | .398** | .438** | .331** | .539** | .503** | .445** | .280* | .451** | .162 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .001 | .000 | .000 | .004 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .014 | .000 | .162 | ||

| C01 | Inadequate/ Inaccurate Design Information | Correlation | .402** | .473** | .312** | .420** | .486** | .355** | .418** | .273* | .417** | .224 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | .000 | .006 | .000 | .000 | .002 | .000 | .017 | .000 | .052 | ||

| C06 | Inappropriate Contract Form | Correlation | .566** | .414** | .443** | .304** | .557** | .585** | .499** | .182 | .455** | .115 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .000 | .000 | .000 | .008 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .116 | .000 | .324 | ||

Appendix I. Spearman coefficients and p-value between the most frequented: Types of variations/claims and causes

| TYPE (Frequency) | T16 | T23 | T38 | T45 | T31 | T34 | T25 | T07 | T09 | T10 | ||

| CAUSE AVOIDABILITY |

CORRELATION (Coefficients) |

Delayed drawings or instructions | A variation or significant change to the quantities | Ambiguity in Documents | Acceleration of Works | An omission of work forming | Delayed payment | Shortage of personnel or goods | Rejection of defective plant and / or materials | Revised methods of working due to poor progress | Delay damages | |

| C10 | Inappropriate Contractor Selection | Correlation | .066 | .231* | .283* | .064 | .100 | -.075 | -.034 | .141 | .127 | .114 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .570 | .045 | .013 | .584 | .390 | .521 | .772 | .225 | .273 | .325 | ||

| C13 | Inappropriate Payment Method | Correlation | .096 | .084 | .268* | .334** | .405** | -.022 | .208 | .101 | .133 | .136 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .411 | .473 | .019 | .003 | .000 | .852 | .072 | .385 | .251 | .243 | ||

| C06 | Inappropriate Contract Form | Correlation | .229* | .318** | .294** | .142 | .458** | .083 | -.010 | .082 | .173 | .286* |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .046 | .005 | .010 | .221 | .000 | .478 | .933 | .479 | .135 | .012 | ||

| C05 | Inappropriate Contract Type | Correlation | .333** | .170 | .168 | .157 | .264* | .096 | -.081 | .046 | .348** | .192 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .003 | .142 | .147 | .175 | .021 | .412 | .489 | .695 | .002 | .097 | ||

| C01 | Inadequate/ Inaccurate Design | Correlation | -.067 | .020 | .149 | .162 | .109 | .077 | .024 | .198 | .262* | .173 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .566 | .863 | .198 | .163 | .348 | .509 | .834 | .086 | .022 | .136 | ||

| C24 | Inadequate Site Investigation | Correlation | .055 | .197 | .250* | .012 | .162 | -.080 | -.076 | .214 | .259* | .212 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .635 | .088 | .029 | .920 | .161 | .494 | .513 | .064 | .024 | .066 | ||

| C04 | Unclear & Inadequate Specifications | Correlation | -.041 | .027 | .068 | .035 | -.025 | .012 | -.067 | .117 | .235* | .070 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .724 | .814 | .560 | .765 | .831 | .915 | .567 | .313 | .041 | .546 | ||

| C02 | Inadequate/ Inaccurate Design Information | Correlation | .148 | .175 | .290* | .091 | .181 | .109 | .032 | .393** | .361** | .373** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .202 | .131 | .011 | .432 | .117 | .350 | .782 | .000 | .001 | .001 | ||

| C08 | Inadequate Contract Documentation | Correlation | .139 | .162 | .227* | .276* | .176 | .170 | .008 | .211 | .397** | .335** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .230 | .163 | .048 | .016 | .129 | .141 | .945 | .068 | .000 | .003 | ||

| C07 | Inadequate Contract Administration | Correlation | .055 | -.163 | .148 | -.062 | .201 | .010 | .022 | .169 | .094 | -.032 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .639 | .158 | .203 | .597 | .082 | .930 | .852 | .145 | .421 | .782 | ||

| C09 | Incomplete Tender Information | Correlation | .101 | .216 | .051 | .192 | .180 | .022 | .056 | .164 | .329** | .167 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .387 | .060 | .664 | .096 | .120 | .851 | .629 | .156 | .004 | .150 | ||

| ** indicates the statistically highly positive correlation. | ||||||||||||

Appendix J. Spearman coefficient and p-value between the most impacted types of variations/claims and most avoid ability causes

| CAUSE AVOIDABILITY | TYPE (IMPACT) | T39 | T47 | T16 | T41 | T27 | T38 | T33 | T23 | T26 | T48 | |

| CORRELATION | Loss of works caused Employer’s Risks | Client’s Breach of Contract | Delayed drawings or instructions | Force Majeure | Delays caused by authorities | Ambiguity in Documents | Changes in legislation | A variation or significant change to the quantities | Employer’s delay or impediment | Inflation / Price Escalation | ||

| C10 | Inappropriate Contractor Selection | Correlation Coefficient | .222 | .307** | .305** | .244* | .308** | .185 | .359** | .227* | .179 | .294** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .054 | .007 | .007 | .034 | .007 | .109 | .001 | .048 | .121 | .010 | ||

| C13 | Inappropriate Payment Method | Correlation Coefficient | .143 | .370** | .206 | .240* | .271* | .360** | .226* | .205 | .190 | .042 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .216 | .001 | .074 | .037 | .018 | .001 | .050 | .076 | .099 | .717 | ||

| C06 | Inappropriate Contract Form | Correlation Coefficient | .301** | .354** | .330** | .237* | .510** | .520** | .434** | .186 | .459** | .150 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .008 | .002 | .004 | .039 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .109 | .000 | .195 | ||

| C05 | Inappropriate Contract Type (Strategy) | Correlation | .251* | .275* | .295** | .183 | .388** | .298** | .352** | .145 | .258* | .198 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .029 | .016 | .010 | .113 | .001 | .009 | .002 | .212 | .025 | .087 | ||

| C01 | Inadequate/ Inaccurate Design Information | Correlation | .070 | .295** | .055 | .066 | .073 | .176 | .299** | .132 | .165 | .088 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .548 | .010 | .635 | .572 | .533 | .128 | .009 | .256 | .153 | .449 | ||

| C24 | Inadequate Site Investigation | Correlation | .164 | .266* | .222 | .184 | .302** | .254* | .306** | .303** | .248* | .241* |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .156 | .020 | .054 | .111 | .008 | .027 | .007 | .008 | .030 | .036 | ||

| C04 | Unclear & Inadequate Specifications | Correlation | .043 | .166 | .006 | -.008 | .073 | .064 | .160 | .210 | .063 | .104 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .712 | .151 | .957 | .949 | .531 | .580 | .169 | .069 | .590 | .369 | ||

| C02 | Inadequate/ Inaccurate Design Information | Correlation | .178 | .183 | .142 | .325** | .381** | .229* | .415** | .145 | .344** | .116 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .125 | .115 | .221 | .004 | .001 | .046 | .000 | .212 | .002 | .318 | ||

| C08 | Inadequate Contract Documentation | Correlation | .219 | .310** | .227* | .191 | .434** | .278* | .483** | .193 | .305** | .342** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .058 | .006 | .048 | .099 | .000 | .015 | .000 | .094 | .007 | .003 | ||

| C07 | Inadequate Contract Administration | Correlation | .016 | .190 | .086 | .048 | .152 | .127 | .277* | .071 | .171 | .183 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .893 | .099 | .458 | .679 | .190 | .276 | .015 | .540 | .140 | .113 | ||

| C09 | Incomplete Tender Information | Correlation | .097 | .095 | .062 | .176 | .116 | -.033 | .164 | .214 | .135 | .115 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | .403 | .414 | .592 | .128 | .317 | .779 | .157 | .063 | .247 | .322 | ||

| ** indicates the statistically highly positive correlation. | ||||||||||||

References

- Amin Sherif, Abdelalim, A.M., 2023, “Delay Analysis Techniques and Claim Assessment in Construction Projects,” International Journal of Engineering, Management, and Humanities (IJEMH), Vol.10, Issue.2, 316-325. [CrossRef]

- Kumaraswamy, M.M. Conflicts, Claims and Disputes in Construction Engineering. Constr. Archit. Manag. 1997, 4, 95–111.

- Abdelalim, A.M. Risks Affecting the Delivery of Construction Projects in Egypt: Identifying, Assessing and Response. In Project Management and BIM for Sustainable Modern Cities; Springer International Publishing: Basel, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 125–154. [CrossRef]

- FIDIC. Conditions of Contract for Construction for Building and Engineering Works Designed by the Employer. 1999; ISBN 2-88432-022-9.

- Abdelalim, A.M.; El Nawawy, O.A.; Bassiony, M.S. Decision Supporting System for Risk Assessment in Construction Projects: AHP-Simulation Based. IPASJ Int. J. Comput. Sci. 2016, 4, 22–36. [CrossRef]

- Khedr, R.; Abdelalim, A.M. Predictors for the Success and Survival of Construction Firms in Egypt. Int. J. Manag. Commer. Innov. 2021, 9, 192–201.

- Abdelalim, A.M.; Abo. Elsaud, Y. Integrating BIM-Based Simulation Technique for Sustainable Building Design. In Project Management and BIM for Sustainable Modern Cities; Springer International Publishing: Basel, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 209–238. [CrossRef]

- Hassanen, M. A. H., & Abdelalim, A. M., 2022, A Proposed Approach for a Balanced Construction Contract for Mega Industrial Projects in Egypt, International Journal of Management and Commerce Innovations ISSN 2348-7585, Vol.10, Issue.1, pp: 217-229. [CrossRef]

- Abdelalim, A.M.; Said, S.O.M. Dynamic Labour Tracking System in Construction Project Using BIM Technology. Int. J. Civ. Struct. Eng. Res. 2021, 9, 10–20.

- Van Eck, N.; Waltman, L. Software Survey: VOS-viewer, a Computer Program for Bibliometric Mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538.

- Abdelalim, A.M.; Eldesouky, M.A. Evaluating Contracting Companies According to Quality Management System Requirements in Construction Projects. Int. J. Eng. Manag. Hum. 2021, 2, 158–169.

- Ostrovsky, R.; Rabani, Y.; Schulman, L.J.; Swamy, C. The Effectiveness of Lloyd-Type Methods for the K-Means Problem. J. ACM 2013, 59, 1–22.

- Pai, S.G.; Sanayei, M.; Smith, I.F. Model-Class Selection Using Clustering and Classification for Structural Identification and Prediction. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2021, 35, 04020051.

- Yuan, C.; Yang, H. Research on K-Value Selection Method of K-Means Clustering Algorithm. J. 2019, 2, 226–235.

- Yousri, E.; Sayed, A.E.B.; Farag, M.A.M.; Abdelalim, A.M. Risk Identification of Building Construction Projects in Egypt. Buildings 2023, 13, 1084. Available online: https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13041084 (accessed on [Date of Access]).

- Sherif, A.; Abdelalim, A.M. Delay Analysis Techniques and Claim Assessment in Construction Projects. Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Younis, R.E.A.; Abdelkhalek, H.; Abdelalim, A.M. Project Risk Management During Construction Stage According to International Contract (FIDIC). Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Abdelalim, A.M.; Elbeltagi, E.; Mekky, A.A. Factors Affecting Productivity and Improvement in Building Construction Sites. Int. J. Prod. Qual. Manag. 2019, 27, 464–494. [CrossRef]

- Abdelalim, A.M.; Khalil, E.B.; Saif, A.A. The Effect of Using the Value Engineering Approach in Enhancing the Role of Consulting Firms in the Construction Industry in Egypt. Int. J. Adv. Res. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2021, 8, 16531–16539.

- Khedr, R.; Abdelalim, A.M. The Impact of Strategic Management on Project Performance of Construction Firms in Egypt. Int. J. Manag. Commer. Innov. 2021, 9, 202–211.

- Hassanen, M. A. H., & Abdelalim, A. M. (2022). Risk Identification and Assessment of Mega Industrial Projects in Egypt. International Journal of Management and Commerce Innovation (IJMCI), 10(1), 187-199. [CrossRef]

- Medhat, W., Abdelkhalek, H., & Abdelalim, A. M. (2023). A Comparative Study of the International Construction Contract (FIDIC Red Book 1999) and the Domestic Contract in Egypt (the Administrative Law 182 for 2018). [CrossRef]

- Abdelalim, A.M.; Sherif, A.; Abdelalkhaleq, H. Criteria of selecting appropriate Delay Analysis Methods (DAM) for mega construction projects. J. Eng. Manag. Competitiveness 2023, 13, 79–93. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Research Methodology.

Figure 2.

Co-occurrence of the top keywords.

Figure 3.

Respondent’s Profile (Groups PC01, PC02, PC03).

Figure 4.

Respondent’s Profile (Groups PC04, PC05, PC06).

Figure 5.

Elbow plot for the distortion score for the number of clusters.

Table 1.

Classification of Claims according to FIDIC 1999.

| No. | FIDIC Sub-Clause | Claim Description | Claim Party | Sort of Claim (Additional) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Employer (E) |

Contractor (C) |

Cost (C) |

Profit (P) |

Time (T) |

|||

| 1 | 4.2.a | Failure to extend validity of the performance security | E | C | |||

| 2 | 4.2.b | Failure to pay agreed amount due. | E | C | |||

| 3 | 4.14 | Avoidance of Interference | E | C | |||

| 4 | 4.16 | Damages, losses and expenses resulting from Transport | E | C | |||

| 5 | 4.19 | Payment of electricity, water or gas | E | C | |||

| 6 | 4.2 | Employer’s equipment or free-issue materials | E | C | |||

| 7 | 7.5 | Rejection of defective plant and / or materials | E | C | |||

| 8 | 7.6 | Contractor’s failure to remedy defects | E | C | |||

| 9 | 8.6 | Revised methods of working due to poor rate of progress | E | C | |||

| 10 | 8.7 | Delay damages | E | C | |||

| 11 | 9.4 | Failed tests on completion | E | C | |||

| 12 | 11.4 | A failure to rectify defects | E | C | |||

| 13 | 15.4 | Termination by employer | E | C | |||

| 14 | 18.1 | Contractor’s failure to insure | E | C | |||

| 15 | 18.2 | Contractor’s inability to insure | E | C | |||

| 16 | 1.9 | Delayed drawings or instructions | C | C | P | T | |

| 17 | 2.1 | Right of access to, or possession of the site | C | C | P | T | |

| 18 | 4.2 | Delay of performance security payment after performance certificate issuing | C | C | P | T | |

| 19 | 4.7 | Errors in setting out information | C | C | P | T | |

| 20 | 4.12 | Unforeseen physical conditions | C | C | T | ||

| 21 | 4.24 | Fossils, ancient artefacts, archaeological or geological items | C | C | T | ||

| 22 | 7.4 | Additional tests instructed by the engineer | C | C | P | T | |

| 23 | 8.4.a | A variation or significant change to the quantities | C | T | |||

| 24 | 8.4.c | Unusual bad weather | C | T | |||

| 25 | 8.4.d | Shortage of personnel or goods | C | T | |||

| 26 | 8.4.e | Employer’s delay or impediment | C | T | |||

| 27 | 8.5 | Delays caused by authorities | C | T | |||

| 28 | 8.9 | Suspension and/or resuming work after suspension | C | C | T | ||

| 29 | 10.2 | The Employer using part of the works | C | C | P | ||

| 30 | 10.3 | Prevention from undertaking tests on completion | C | C | P | T | |

| 31 | 12.4 | An omission of works | C | C | T | ||

| 32 | 13.2 | An adopted value engineering proposal | C | C | P | ||

| 33 | 13.7 | Changes in legislation | C | C | T | ||

| 34 | 14.8 | Delayed payment | C | C | |||

| 35 | 16.1 | Suspension initiated by the contractor | C | C | P | T | |