Preprint

Article

Second Victims among Austrian Nurses (SeViD-A2 Study)

Altmetrics

Downloads

188

Views

131

Comments

0

A peer-reviewed article of this preprint also exists.

This version is not peer-reviewed

Submitted:

26 August 2024

Posted:

28 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Alerts

Abstract

Background: The Second Victim Phenomenon (SVP) significantly impacts the well-being of healthcare professionals and patient safety. While SVP has been explored in various healthcare settings, there is limited data on its prevalence and associated factors among nurses in Austria. This study investigates the prevalence, symptomatology, and preferred support measures for SVP among Austrian nurses. Methods: A nationwide, cross-sectional, anonymous online survey was conducted using the SeViD questionnaire (Second Victims in German-speaking Countries), which includes the Big Five Inventory-10 (BFI-10). Statistical analyses included binary logistic regression and multiple linear regression using the bootstrapping, bias-corrected and accelerated (BCa) method based on 5000 bootstrap samples. Results: 928 participants responded to the questionnaire. Among the respondents, 81.58% (744/912) identified as Second Victims (SVs). The primary cause of becoming a SV was aggressive behavior from patients or relatives. Females reported a higher symptom load than males, and higher agreeableness was linked to increased symptom severity. Notably, 92.47% of SVs who sought help preferred support from colleagues, and the most pronounced desire among participants was to process the event for better understanding. Conclusions: The prevalence of SVP among Austrian nurses is alarmingly high, with aggressive behavior identified as a significant trigger. The findings emphasize the necessity for tailored support strategies, including peer support and systematic organizational interventions to mitigate the impact of SVP on nurses and to improve overall patient care. Further research should focus on developing and implementing effective prevention and intervention programs for healthcare professionals in similar settings.

Keywords:

Subject: Public Health and Healthcare - Public Health and Health Services

1. Introduction

The healthcare sector is fraught with substantial risks, affecting both patients and healthcare practitioners [1]. As societal evolution outpaces the adaptability of healthcare systems, technological advancements exacerbate the industry's inefficiencies [2,3]. The European Commission's inquiry into the costs of unsafe care highlights the frequent occurrence of complications among hospitalized patients, many of which are preventable [4]. These complications not only deteriorate patients' quality of life but also erode trust in healthcare institutions [5].

Therefore, these events harm patients as well as subject healthcare professionals to distress and trauma, possibly making them Second Victims (SVs) [6]. Coined by Albert Wu in 2000, the Second Victim Phenomenon (SVP) initially focused on physicians traumatized by medical mishaps, identifying them as SVs and the patients and their families as First Victims [7]. Scott et al. later expanded this concept to include the trauma experienced by all healthcare workers following adverse events [8].

The European Researcher Network Working on Second Victims (ERNST) recently provided a comprehensive definition of SVs, encompassing any healthcare worker affected by unforeseen adverse patient events or inadvertent errors [9]. The psychological ramifications of such events range from guilt and anxiety to diminished confidence and even contemplation of self-harm. Importantly, SVP not only affects the well-being of SVs but also undermines the quality of care provided to subsequent patients.

Global efforts have examined the prevalence of SVP [10,11], with significant studies conducted in Germany and Austria [12,13,14]. A survey of German nurses revealed a substantial proportion experiencing SVP, often with prolonged recovery periods [15]. Similarly, a recent nationwide survey among Austrian pediatricians uncovered a significant prevalence of self-reported SVs, particularly among outpatient pediatricians [16].

Furthermore, a cross-sectional analysis across Belgian hospitals compared the responses of physicians, midwives, and nurses following adverse events, revealing varied reactions across professions [17]. Nurses, who constitute the largest group among healthcare professionals, play a pivotal role in patient care and often face physical and emotional repercussions following adverse occurrences.

Research suggests that nurses may be reluctant to seek professional support after an incident, due to limited awareness of SVP and inherent barriers [18,19,20,21]. Organizational support mechanisms are crucial in preventing adverse outcomes, such as exacerbation of harm and employee attrition [22,23].

The SeViD-A2 study, conducted in Austria by the Austrian Second Victim Association and the Wiesbaden Institute for Healthcare Economics and Patient Safety (WiHelP), in collaboration with the Austrian Nurses Association (ÖGKV), builds on previous research. It aims to evaluate the prevalence and symptomatology of SVP among Austrian nurses. Additionally, the study also examined preferred support measures as a secondary outcome. The study also seeks to identify demographic, workplace-related, and personality trait determinants associated with the likelihood and severity of SVP. It is well-known that an individual's reaction to stress is influenced not only by personal capacities, such as personality traits and available resources [24,25], but also by the specific characteristics of the stressful situation [26]. Our objective is to gain a deeper understanding of how different factors contribute to stress responses, particularly in the context of adverse events. By analyzing the specific elements and circumstances surrounding these events, we can potentially identify key areas where targeted interventions could be most effective. Such tailored approaches could lead to more effective support mechanisms and improved well-being and resilience among individuals facing similar challenges.

In summary, this study seeks to investigate the multifaceted nature of the Second Victim Phenomenon among Austrian nurses, with the goal of informing supportive interventions and organizational protocols to mitigate its adverse consequences.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Conduction of the SeViD-A2 Survey

This nationwide cross-sectional study was conducted among Austrian nurses utilizing the SeViD questionnaire (Second Victims in German-speaking Countries). The detailed development and validation of the questionnaire are outlined in another publication [27] and referenced in the SeViD-I [12], -II [15], and -III [14] as well as SeViD-A1 [16] publications. The questionnaire, comprising 25 questions across seven dimensions, addressed basic demographics, knowledge and exposure to SVP, the adverse event leading to it, recovery processes, reactions, and support measures. The 10-item short-version of the Big Five Inventory (BFI-10) assessed personality traits (openness, neuroticism, agreeableness, extraversion, and conscientiousness) [28]. Two additional questions were incorporated, one regarding the association of the adverse event leading to SVP with the COVID pandemic, and the other inquiring whether those affected feared legal consequences.

2.2. Survey Methodology

Employing adaptive questioning, only participants identifying as SVs received questions related to the events leading to SVP or their symptoms. Respondents were required to answer all questions before progressing to the next item, but they had the flexibility to revise and change their previous responses if necessary. Additionally, participants were given the opportunity to provide comments or suggestions at the end of the survey.

2.3. Survey Distribution and Data Collection

The survey was distributed via email to members of the Austrian Nurses Association (ÖGKV), totaling approximately 6.000 members. The invitation letter provided a brief overview of the study's objectives, an introduction to SVP, and a link along with a QR code directing participants to the online survey hosted on the SurveyMonkey platform. Data collection was conducted anonymously, with no retention of tokens, cookies, or IP addresses. The study spanned three months, from September 15th to December 12th, 2023.

2.4. Preparation and Re-Coding of Variables for Statistical Analysis

The procedure for preparing and re-coding variables for statistical analysis followed the same methodology as in the SeViD-A1 study, allowing for direct comparisons. The item "SV-status" was dichotomized participants who had experienced SVP once or multiple times were coded as 1, and those who had not as 0. The educational status of the nurses was dichotomized as follows: Bachelor, Master, PhD, and Diploma in Healthcare and Nursing (DGKP - 'Diplom Gesundheits und Krankenpflege') were assigned a value of 1, while qualified nursing assistants, nursing assistants, and persons without job training were assigned a value of 0. Working hours were categorized as follows: full-time was assigned a value of 1, and part-time was assigned a value of 0. Nurses with a leading function were assigned a value of 1, and the others were assigned a value of 0. According to the SeViD-II study, which took place among nursing staff in Germany, we dichotomized nurses working in critical care (e.g., operating theater, intensive care unit, or emergency department) as 1, and all others as 0. To evaluate symptom load, we calculated sum scores for 18 symptoms potentially caused by SVP, based on prior research (see Table 3) [19]. Our goal was to capture the overall symptom burden, rather than focusing on individual symptoms. We used positive scoring items for symptom load, with values assigned as follows: "strongly pronounced" = 1, "weakly pronounced" = 0.5, and both "not at all" and "I don’t know" = 0.

Two additional items in relation to symptoms were assessed but excluded from the sum score: “desire for support,” “desire to process the event”. These two items were considered support desires rather than symptoms. Frequency distributions also for these as well as all other symptoms are reported in the results section. Recovery time from the critical event was measured on a nominal scale: 1 ("less than a day"), 2 ("within a week"), 3 ("within a month"), 4 ("within a year"), 5 ("more than a year"), and 6 ("I have not fully recovered"). It is notable that the item referring to the time from a critical event to full recovery was treated as a nominal variable, indicating that the assigned values do not necessarily reflect the order or ranking. This is because the response option “I did not fully recover until now” could theoretically represent a shorter duration than other response options, considering the time elapsed since the critical event occurred.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis methods also replicated those used in the SeViD-A1 study to ensure comparability.

Descriptive statistics of demographical variables and applied instruments were reported using means (M) with standard deviations (SD) for interval-scaled and numbers (n) with percentages (%) for nominal and ordinal scaled variables independent of the distributional characteristics [29]. All percentage values refer to the denominator of respondents who answered the specific question. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics Version 29 (IBM, New York, NY, USA). A p-value lower than 0.05 was considered significant.

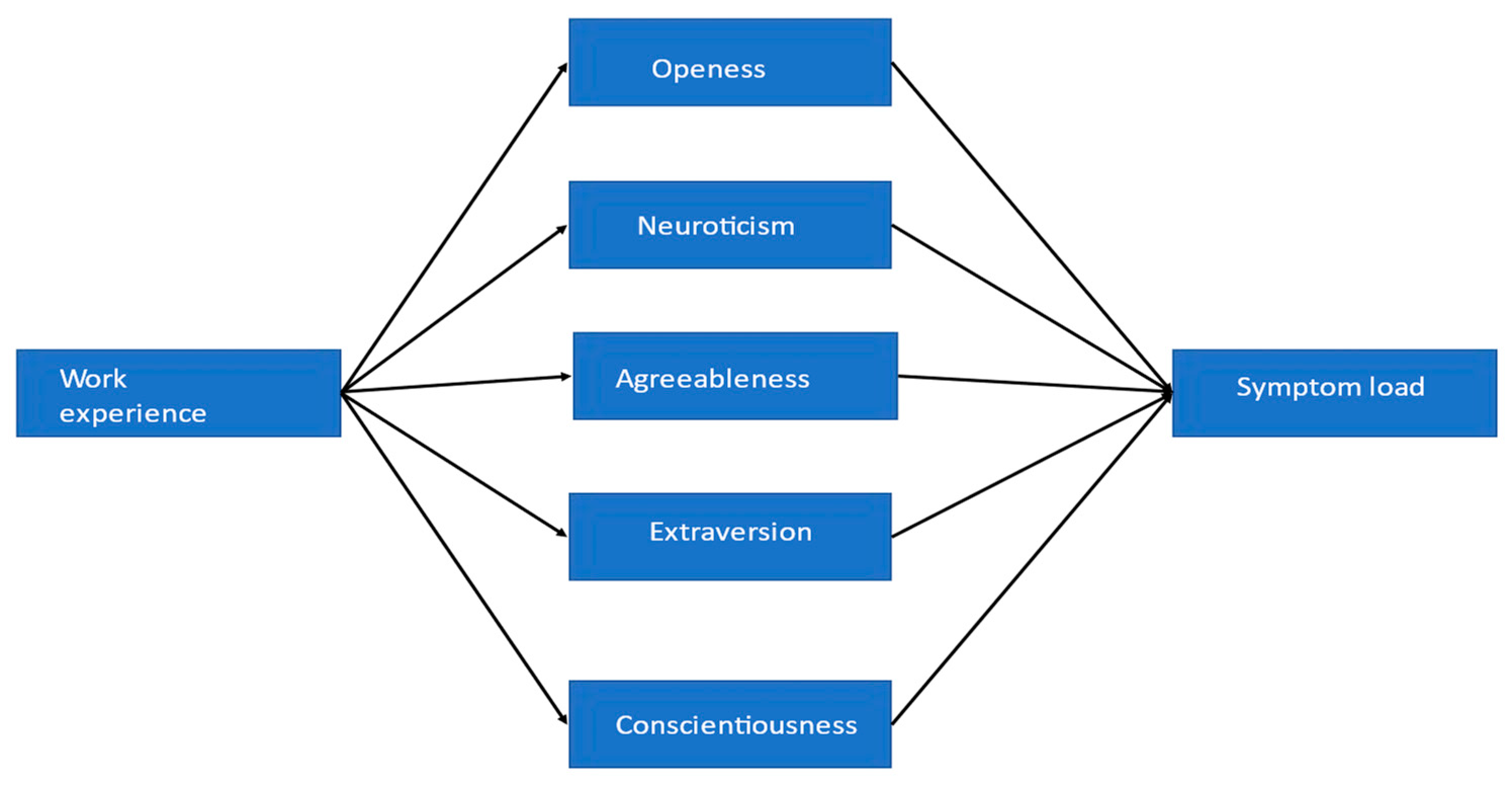

The potential correlation between predictors such as gender, age, length of professional experience, workplace (acute care vs. others), and the five personality dimensions (openness, neuroticism, agreeableness, extraversion, and conscientiousness) on the dichotomous dependent variable (SV experienced at least once: yes vs. no) was assessed using binary logistic regression with bootstrapping (BCa method, 5000 samples). In addition, we also included the types of adverse events as predictors in a multiple linear regression with symptom load as the outcome in the next step. Multiple linear regression with bootstrapping (BCa method, 5000 samples) examined if the independent variables significantly explained symptom load variance. Multicollinearity was checked using the bivariate correlation matrix, tolerance, and variance-inflation factor (VIF). If detected, predictor variables were centered. Based on previous findings, this study tested the indirect effects of work experience on symptom load via five personality traits using model 4 for parallel mediators from the PROCESS macro for SPSS v4. Bootstrapping with a 95% confidence interval based on 5000 samples estimated direct, indirect, and total effects, as shown in Figure 1.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Baseline Analysis

Out of the 6000 participants addressed, 928 responded to the questionnaire, among these respondents, 82% successfully completed the entire survey. The mean time for participation was 9min and 25s. Table 1 shows the participants baseline characteristics.

Most participants were female (79.63%), 20.04% were male and 0.3% stated having a diverse (non-binary) gender identity. The mean age of the participants was 42.42 years (SD 10.36; range 18-65) and the mean work experience was 18.64 years (SD 11.50; range 1-45). Most participants worked full-time (61.96%) and in shifts (70.48%).

Regarding their acquaintance with the term "Second Victim", 67.54% (616) of the participants indicated to not having heard of it prior to the survey. After a brief explanation, 81.58% (744) stated that they now recognize themselves as Second Victims. A substantial majority (63.38%) reported being a SV on multiple occasions, as shown in Figure 2. Of responding participants 18.42% indicated that they did not identify as SVs. Furthermore, 59.36% (425) mentioned that they were SVs within the past twelve months.

Most participants identified aggressive behavior of patients or their relatives (37.43%) as the primary event leading to SVP, followed by the unexpected death or suicide of a patient (24.02%), as shown in Table 2. Notably, 18.58% of the key incidents leading to SVP were related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Some participants specified their key events further (similar answers were summarized):

“Medication mixed up, patient sedated”

“Missed care”

“Lifeless child at birth”

“Bullying from colleagues”

“Reports of domestic violence”

“Aggressive behavior by doctors”

“Severely injured patient”

“Stillbirths”

“Death of young patients”

“Lack of patient care with fatal outcome”

“Serious injury to a young patient due to external violence”

“Suicide attempt by a patient”

“Unjustified accusations by a relative”

“Postpartum hemorrhage”

“Colleague who died on her own ward as a patient on my shift”

“Aggressive behavior of a nurse towards a patient”

“Sexual harassment by patients”

“Number of deaths during COVID”

“Verbally aggressive behavior by middle managers”

“Expected death of a very young patient”

“Patient bled to death within 15 min”

“Dismissal of a colleague”

“Moral stress”

Over half of the participants (56.56%, 405) received help after a traumatizing adverse event; 30.73% (220) did not receive any help but had not asked for it, while 12.71% (91) stated they were denied help even though they actively asked for it. The vast majority received help from their colleagues, as shown in Table 3.

The recovery time of the SVs varied: 29.91% (198) recovered within one month, 27.95% (185) within one week. 12.99% (86) stated that they had not yet fully recovered. In relation to their reactions to the adverse event, participants were presented with possible symptoms and asked to rate them according to how severe they were. The most pronounced symptoms were insomnia or excessive need for sleep, reliving the situation in similar professional situations and psychosomatic reactions like head- or backaches as shown in Table 4. Desire to receive support from others was strongly pronounced in 39.43% (261) participants. However, the most expressed feeling was the desire to process the event for better understanding, it being strongly pronounced in 46.22% (306) of the respondents.

When asked about the fear of legal consequences, the majority (83.83%, 555) of respondents stated that it was weakly or not pronounced at all. Only 14.5% (96) stated that the fear of legal consequences was strongly pronounced.

Participants were also asked to rate possible supporting measures. Support measures were scored on a five-point descending Likert scale ranging from one, “very helpful”, to five, “not helpful at all” (“not helpful at all” = 5, “rather not helpful” = 4, “neutral” = 3, “rather helpful” = 2 and “very helpful” = 1) and is shown in Table 5.

Overall, support measures are viewed positively, indicating moderate to high helpfulness. Non-SVs find professional counseling more helpful than SVs, while SVs place greater importance on discussing emotional and ethical thoughts and receiving formal emotional support. SVs also prefer quick crisis intervention, finding it more helpful than Non-SVs. Both groups equally value clear and timely information, support for work continuation, and effective communication with patients and relatives. SVs consider guidelines during serious events and secure reporting for future prevention more helpful, whereas Non-SVs rate legal counseling as more beneficial.

3.2. Factors Associated with the Likelihood of Becoming a Second Victim

The results of the binary logistic regression analysis showed that being female was correlated with a higher likelihood of becoming a SV (regression Coefficient B = -0.53, BCa 95% CI [-0.99, -0.13]). The odds ratio (OR) was 0.59, with a 95% CI [0.38, 0.91]. Other healthcare worker-centered and work environment-related predictors were not correlated with a higher or lower chance of becoming a SV as shown in Table 6.

3.3. Factors Associated with the Symptom Load after the SV Experience

We conducted a multiple linear regression analysis to examine the correlation between demographic factors, healthcare worker-related characteristics, workplace-related factors, and personality traits and the symptom load experienced after a SV experience. The outcome variable was the sum and severity of symptoms suffered following an SV experience (Table 7).

The analysis indicates that among the variables tested, gender and agreeableness were significantly correlated to the symptom load experienced after a SV experience. Females reported a higher symptom load compared to males, whereas higher agreeableness was linked to a higher symptom load. Other factors, including age, professional experience, education, job status, management role, specific workplace, openness, extraversion, and neuroticism, were not significant predictors of symptom load.

In the next step, we included the types of adverse events in the regression equation as shown in Table 8.

The results show that no demographic, workplace-related, or personality trait factor was significant in predicting symptom load after including the types of adverse events in the regression equation. Interestingly, all types of incidents involving patient harm, unexpected death or suicide of a patient, unexpected death or suicide of a colleague, and aggressive behavior by patients or relatives were more strongly correlated with higher symptom load than events without patient harm.

3.4. Testing the Mediational Model

Based on previously published studies, we tested a mediational model with personality traits as a mediator in the relationship between years of professional experience and symptom load after the SV experience using SPSS Process macro, Model 4 for parallel mediators.

The results revealed neither significant direct (unstandardized regression coefficient (B = −0.004, bootstrapped 95%CI [−0.03, 0.002]) nor indirect effects of professional experience on symptom load (see Table 9). The total effect was also not significant (B=−0.008 bootstrapped 95%CI [−0.04, 0.002]). The whole model with predictor and mediator predicted 11 % of the symptom load variance, F(6,756)=1.64, p=0.13.

4. Discussion

The present study reveals several critical insights into the Second Victim Phenomenon (SVP) among Austrian nurses. A striking 82% of the nurses surveyed identified themselves as Second Victims, underscoring the pervasive nature of SVP in this group. The most common type of event leading to SVP was aggressive behavior from patients or relatives, reported by 37.43% of participants. In terms of symptoms, insomnia or excessive need for sleep, reliving the situation in similar professional contexts, and psychosomatic reactions such as headaches and backaches were the most frequently reported. The desire to process the event for better understanding and the need for support from others were also strongly pronounced among respondents. Colleagues emerged as the most favored source of support, with 92.47% of participants seeking help from their peers, highlighting the critical role of peer support in coping with SVP.

The notable decrease in participants over the age of 60 compared to SeViD-A1 [16], despite similar levels of experience, introduces a critical demographic shift. This younger sample, with higher neuroticism and symptom load, suggests that age and personality traits play a significant role in how healthcare professionals experience and cope with serious events. Younger professionals, possibly less experienced in managing high-stress situations, may exhibit heightened vulnerability, leading to more pronounced emotional and psychological symptoms [30]. This demographic shift underscores the need for tailored interventions that consider the unique stress responses and coping mechanisms of younger healthcare workers.

The study's finding of no significant correlation between most personality traits and SV status, except for agreeableness in relation to event type, points to a complex interaction between individual differences and the impact of serious events. The restricted variance in personality traits within the sample might obscure potential relationships, suggesting that personality may influence second victimization in more nuanced ways than previously understood. Interestingly, the study's higher observed levels of neuroticism among nurses may be influenced by recent research indicating that younger professionals report higher neuroticism compared to older cohorts, potentially affecting their responses to adverse events [31].

The persistent finding that women are at a higher risk of becoming SVs aligns with some previous research [12] but stays in contrast to a previous survey among German nurses [15]. It raises questions about underlying causes. The gender disparity in SVP risk may be influenced by specific work environments and roles predominantly occupied by men and women, suggesting that job-specific factors and gender-specific personality traits both play significant roles in susceptibility to SVP [32,33].

The study's failure to identify significant mediation effects could be attributed to restricted data variance and a younger sample. Ceiling effects may limit the ability to observe meaningful correlations, indicating that data variability is crucial for detecting mediation effects. Future studies should employ longitudinal approaches and seek to include a broader range of data points.

The study emphasizes the type of event as a primary determinant of SV, highlighting the importance of event severity and nature in shaping the impact on healthcare workers. Violence against nurses is a well-documented issue, with significant negative impacts on their personal and professional well-being. This includes verbal abuse, physical violence, and sexual harassment, leading to increased job stress, low morale, and higher turnover rates [34,35,36,37,38]. The high prevalence of workplace violence in Austria could partly explain the elevated rate of SVP among nurses in this study. This finding underscores the need for robust systems to address various types of events, particularly through targeted prevention strategies like de-escalation training and communication [39,40].

The study reveals a divergence in support needs, with SVs prioritizing emotional support and non-second victims valuing legal consultation. If healthcare workers do not identify themselves as SVs, they may even still exhibit symptoms after an adverse event as first demonstrated in the SeViD-IX study among German general practitioners [41]. Implementing support strategies that address these specific needs can enhance the overall effectiveness of interventions and ensure that all affected healthcare professionals receive appropriate and comprehensive support.

The higher prevalence of SVP among Austrian nurses (82%) may be influenced by missed nursing care (MNC), which is defined as any required patient care that is omitted or delayed [42]. The MISS-Care Austria 2022 study found that 84.4% of nurses reported omitting at least one nursing intervention in the preceding two weeks. Factors contributing to MNC include multitasking, staff shortages, and personal exhaustion. This high rate of MNC could lead to SVP, particularly in environments where mistakes are made due to resource limitations [43].

Previous studies suggest that nurses may make more external attributions following serious errors, potentially hindering constructive responses and learning from mistakes. This tendency may be linked to the strong professional ethos among nurses, which emphasizes personal responsibility. Addressing this issue requires careful management to encourage reflective practice and positive behavior change following errors [44].

Regardless of the type or severity of the adverse event, nurses report significant physical and emotional manifestations, underscoring the need for appropriate support. However, many do not proactively seek help, possibly due to limited awareness of SVP or perceived barriers [19]. Support from colleagues is often the most appreciated, but systematic organizational interventions are necessary to ensure all healthcare workers receive the support they need [17].

While this study provides valuable insights into the Second Victim Phenomenon (SVP) among Austrian nurses, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the response rate of 15.47%, although reasonable for voluntary surveys, raises concerns about response bias. It is possible that those who participated in the survey were more likely to have experienced or been affected by SVP, potentially leading to an overestimation of the prevalence of SVP among Austrian nurses. Conversely, those who did not participate might have different experiences or less severe symptoms, which could mean that the findings do not fully represent the entire nursing population.

Another potential limitation is social desirability bias, which may have influenced how participants responded to the survey questions. Nurses may have felt compelled to provide answers they perceived as socially acceptable or aligned with the expectations of their profession, particularly in questions related to admitting mistakes or discussing the severity of their symptoms. This bias could result in an underreporting of more sensitive issues, such as the impact of SVP on their mental health or the extent of missed nursing care due to resource constraints.

The cross-sectional design of the study limits the ability to draw causal inferences. While associations between factors like personality traits, event types, and SVP symptomatology were observed, it is challenging to determine the direction of these relationships or to account for potential confounding variables. Longitudinal studies would be needed to better understand the temporal dynamics of SVP and the long-term effects on healthcare professionals.

The reliance on self-reported data also introduces potential inaccuracies due to recall bias. Participants may have difficulties with accurately remembering the details of past events or their reactions to them, particularly when these events occurred a long time ago. However, it is important to note that the key incidents reported, such as aggressive behavior or unexpected patient deaths, were often drastic and highly traumatic. Such events are likely to leave a strong impression, potentially alleviating some of the concerns about recall bias, as individuals are more likely to vividly remember and accurately report severe and emotionally charged experiences.

In light of these limitations, the findings of this study should be interpreted with caution. Future research could address these issues by incorporating longitudinal designs where possible to better capture the complex dynamics of SVP among healthcare workers.

However, it is important to note that the results of this study are consistent with numerous other studies within the SeViD study program and the broader body of research on the SVP. These studies have consistently demonstrated high prevalences of SVP across various healthcare professions and settings, as well as a strong need and desire for peer support programs. The robust findings from these studies further support the conclusions of our research, underscoring the critical importance of implementing effective support systems to address the pervasive impact of SVP in healthcare.

5. Conclusions

The findings from this study offer critical insights into the prevalence, causes, and consequences of the Second Victim Phenomenon (SVP) among Austrian nurses, highlighting the need for targeted interventions and systemic changes within healthcare organizations. With 82% of the nurses surveyed identifying as Second Victims, it is evident that SVP is a pervasive issue in nursing, exacerbated by both the nature of the work environment and the specific stressors encountered by nurses.

This study underscores the urgent need for healthcare organizations to recognize and address the Second Victim Phenomenon among nurses. By implementing comprehensive support systems, improving workplace safety, and addressing the systemic issues that contribute to SVP, healthcare institutions can not only improve the well-being of their nursing staff but also enhance the overall quality of patient care. The findings of this study should serve as a call to action for healthcare leaders to prioritize the mental and emotional health of their workers, recognizing that the well-being of nurses is integral to the success of the healthcare system as a whole.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.P., P.T and R.S.; methodology, R.S. and H.R.; software, H.R.; formal analysis, H.R. and M.T.-K.; investigation, E.P., P.T., H.R.; writing—original draft preparation, H.R., E.P., M.T.-K., RS; writing—review and editing, P.T., V.K.; supervision, R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study after the concept was presented to a local ethics committee in Vienna.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all participants for their contributions to this study as well as the Austrian Nurses Association (ÖGKV) for their support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Richarz, S. Psychische Belastung in der Gefährdungsbeurteilung. Zbl Arbeitsmed 2018, 68, 334–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersten, M.; Kozak, A.; Wendeler, D.; Paderow, L.; Nübling, M.; Nienhaus, A. Psychological stress and strain on employees in dialysis facilities: a cross-sectional study with the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2014, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyng, H.B.; Macrae, C.; Guise, V.; Haraldseid-Driftland, C.; Fagerdal, B.; Schibevaag, L.; Alsvik, J.G.; Wiig, S. Balancing adaptation and innovation for resilience in healthcare - a metasynthesis of narratives. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbabiaka, T.B.; Lietz, M.; Mira, J.J.; Warner, B. A literature-based economic evaluation of healthcare preventable adverse events in Europe. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2017, 29, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jha, A.K.; Larizgoitia, I.; Audera-Lopez, C.; Prasopa-Plaizier, N.; Waters, H.; Bates, D.W. The global burden of unsafe medical care: analytic modelling of observational studies. BMJ quality & safety 2013, 22, 809–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterman, A.D.; Garbutt, J.; Hazel, E.; Dunagan, W.C.; Levinson, W.; Fraser, V.J.; Gallagher, T.H. The emotional impact of medical errors on practicing physicians in the United States and Canada. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2007, 33, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, A.W. Medical error: the second victim. The doctor who makes the mistake needs help too. BMJ 2000, 320, 726–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.D.; Hirschinger, L.E.; Cox, K.R.; McCoig, M.; Brandt, J.; Hall, L.W. The natural history of recovery for the healthcare provider "second victim" after adverse patient events. Qual. Saf. Health Care 2009, 18, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhaecht, K.; Seys, D.; Russotto, S.; Strametz, R.; Mira, J.; Sigurgeirsdóttir, S.; Wu, A.W.; Põlluste, K.; Popovici, D.G.; Sfetcu, R.; et al. An Evidence and Consensus-Based Definition of Second Victim: A Strategic Topic in Healthcare Quality, Patient Safety, Person-Centeredness and Human Resource Management. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seys, D.; Wu, A.W.; van Gerven, E.; Vleugels, A.; Euwema, M.; Panella, M.; Scott, S.D.; Conway, J.; Sermeus, W.; Vanhaecht, K. Health care professionals as second victims after adverse events: a systematic review. Eval. Health Prof. 2013, 36, 135–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, I.M.; Moretti, F.; Purgato, M.; Barbui, C.; Wu, A.W.; Rimondini, M. Psychological and Psychosomatic Symptoms of Second Victims of Adverse Events: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Patient Saf. 2020, 16, e61–e74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strametz, R.; Koch, P.; Vogelgesang, A.; Burbridge, A.; Rösner, H.; Abloescher, M.; Huf, W.; Ettl, B.; Raspe, M. Prevalence of second victims, risk factors and support strategies among young German physicians in internal medicine (SeViD-I survey). J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2021, 16, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushuven, S.; Trifunovic-Koenig, M.; Bentele, M.; Bentele, S.; Strametz, R.; Klemm, V.; Raspe, M. Self-Assessment and Learning Motivation in the Second Victim Phenomenon. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marung, H.; Strametz, R.; Roesner, H.; Reifferscheid, F.; Petzina, R.; Klemm, V.; Trifunovic-Koenig, M.; Bushuven, S. Second Victims among German Emergency Medical Services Physicians (SeViD-III-Study). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strametz, R.; Fendel, J.C.; Koch, P.; Roesner, H.; Zilezinski, M.; Bushuven, S.; Raspe, M. Prevalence of Second Victims, Risk Factors, and Support Strategies among German Nurses (SeViD-II Survey). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potura, E.; Klemm, V.; Roesner, H.; Sitter, B.; Huscsava, H.; Trifunovic-Koenig, M.; Voitl, P.; Strametz, R. Second Victims among Austrian Pediatricians (SeViD-A1 Study). Healthcare (Basel) 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Gerven, E.; Bruyneel, L.; Panella, M.; Euwema, M.; Sermeus, W.; Vanhaecht, K. Psychological impact and recovery after involvement in a patient safety incident: a repeated measures analysis. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.; Birks, Y.; Hall, J.; Bosanquet, K.; Harden, M.; Iedema, R. The contribution of nurses to incident disclosure: a narrative review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2014, 51, 334–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, R.; Sela, Y.; Halevi Hochwald, I.; Nissanholz-Gannot, R. Nurses' Silence: Understanding the Impacts of Second Victim Phenomenon among Israeli Nurses. Healthcare (Basel) 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.J.; Long, B. Suffering in Silence: Medical Error and its Impact on Health Care Providers. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 54, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullström, S.; Andreen Sachs, M.; Hansson, J.; Ovretveit, J.; Brommels, M. Suffering in silence. A qualitative study of second victims of adverse events. BMJ quality & safety, 2014, 325–331. [CrossRef]

- Mira, J.J.; Lorenzo, S.; Carrillo, I.; Ferrús, L.; Silvestre, C.; Astier, P.; Iglesias-Alonso, F.; Maderuelo, J.A.; Pérez-Pérez, P.; Torijano, M.L.; et al. Lessons learned for reducing the negative impact of adverse events on patients, health professionals and healthcare organizations. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2017, 29, 450–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seys, D.; Panella, M.; Russotto, S.; Strametz, R.; Joaquín Mira, J.; van Wilder, A.; Godderis, L.; Vanhaecht, K. In search of an international multidimensional action plan for second victim support: a narrative review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A.B.; Boyd, C.M.; Dollard, M.; Gillespie, N.; Winefield, A.H.; Stough, C. The role of personality in the job demands-resources model. Career Dev Int 2010, 15, 622–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gashi, D.; Gallopeni, F.; Imeri, G.; Shahini, M.; Bahtiri, S. The relationship between big five personality traits, coping strategies, and emotional problems through the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr Psychol 2022, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, appraisal, and coping, 11. [print.]; Springer: New York, 20]15, ISBN 0826141919.

- Strametz, R.; Rösner, H.; Ablöscher, M.; Huf, W.; Ettl, B.; Raspe, M. Entwicklung und Validation eines Fragebogens zur Beurteilung der Inzidenz und Reaktionen von Second Victims im Deutschsprachigen Raum (SeViD). Zbl Arbeitsmed 2021, 71, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammstedt, B.; John, O.P. Measuring personality in one minute or less: A 10-item short version of the Big Five Inventory in English and German. Journal of Research in Personality 2007, 41, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lydersen, S. Gjennomsnitt og standardavvik eller median og kvartiler? Tidsskr. Nor. Laegeforen. 2020, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Slambrouck, L.; Verschueren, R.; Seys, D.; Bruyneel, L.; Panella, M.; Vanhaecht, K. Second victims among baccalaureate nursing students in the aftermath of a patient safety incident: An exploratory cross-sectional study. J. Prof. Nurs. 2021, 37, 765–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, N.D.; Drewelies, J.; Willis, S.L.; Schaie, K.W.; Ram, N.; Gerstorf, D.; Wagner, J. Acting Like a Baby Boomer? Birth-Cohort Differences in Adults' Personality Trajectories During the Last Half a Century. Psychol. Sci. 2022, 33, 382–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.T.; Terracciano, A.; McCrae, R.R. Gender differences in personality traits across cultures: robust and surprising findings. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 81, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feingold, A. Gender differences in personality: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 116, 429–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boafo, I.M. The effects of workplace respect and violence on nurses' job satisfaction in Ghana: a cross-sectional survey. Hum. Resour. Health 2018, 16, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Civilotti, C.; Berlanda, S.; Iozzino, L. Hospital-Based Healthcare Workers Victims of Workplace Violence in Italy: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafran-Tikva, S.; Zelker, R.; Stern, Z.; Chinitz, D. Workplace violence in a tertiary care Israeli hospital - a systematic analysis of the types of violence, the perpetrators and hospital departments. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2017, 6, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagnucci, N.; Ottonello, G.; Capponi, D.; Catania, G.; Zanini, M.; Aleo, G.; Timmins, F.; Sasso, L.; Bagnasco, A. Predictors of events of violence or aggression against nurses in the workplace: A scoping review. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 1724–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Corbally, M.; Timmins, F. Violence against nurses by patients and visitors in the emergency department: A concept analysis. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 1688–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marquez, S.M.; Chang, C.-H.; Arnetz, J. Effects of a Workplace Violence Intervention on Hospital Employee Perceptions of Organizational Safety. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2020, 62, e716–e724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, M.; Walter, G. Deeskalationstrainings. Nervenheilkunde 2023, 42, 850–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushuven, S.; Trifunovic-Koenig, M.; Bunz, M.; Weinmann-Linne, P.; Klemm, V.; Strametz, R.; Müller, B.S. Applicability and Validity of Second Victim Assessment Instruments among General Practitioners and Healthcare Assistants (SEVID-IX Study). Healthcare (Basel) 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalisch, B.J.; Landstrom, G.L.; Hinshaw, A.S. Missed nursing care: a concept analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2009, 65, 1509–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartaxo, A.; Eberl, I.; Mayer, H. Die MISSCARE-Austria-Studie – Teil I. HBScience 2022, 13, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meurier, C.E.; Vincent, C.A.; Parmar, D.G. Nurses' responses to severity dependent errors: a study of the causal attributions made by nurses following an error. J. Adv. Nurs. 1998, 27, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Parallel-mediation model. Work experience: length of professional experience in years, Openness, neuroticism, agreeableness, extraversion, and conscientiousness: Big Five Personality Traits, Symptom load: the sum of symptoms after SV experience.

Figure 1.

Parallel-mediation model. Work experience: length of professional experience in years, Openness, neuroticism, agreeableness, extraversion, and conscientiousness: Big Five Personality Traits, Symptom load: the sum of symptoms after SV experience.

Figure 2.

Have you ever experienced the SVP yourself? N=912.

Table 1.

Baseline-Characteristics of the participants. N=928.

| Characteristics | Percentage of Participants (n) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 79.63 (739) | |

| Male | 20.04 (186) | ||

| Diverse | 0.3 (3) | ||

| Age | 18-30 years | 15.31 (142) | |

| 31-40 years | 27.15 (252) | ||

| 41-50 years | 31.04 (288) | ||

| 51-60 years | 24.36 (226) | ||

| >60 years | 2.15 (20) | ||

| Work experience | 1-10 years | 31.48 (292) | |

| 11-20 years | 26.4 (245) | ||

| 21-30 years | 24.45 (227) | ||

| >30 years | 17.69 (164) | ||

| Specialization | None | 21.88 (203) | |

| Management tasks | 22.95 (213) | ||

| Intensive care | 20.04 (186) | ||

| Other | 74.34 (690) | ||

| Education | Master | 16.16 (150) | |

| Bachelor | 21.34 (198) | ||

| PhD | 0.97 (9) | ||

| Nursing Diploma | 83.30 (773) | ||

| Nursing Specialist Assistant | 3.32 (30) | ||

| Nursing Assistant | 6.25 (58) | ||

| none | 0.86 (8) |

Table 2.

Types of the most formative adverse event (key experiences). N=716.

| Type of Event | Percentage of Participants (n) |

|---|---|

| Incident with patient harm | 14.25 (102) |

| Incident without patient harm (near miss) | 14.11 (101) |

| Unexpected death/ suicide of a patient | 24.02 (172) |

| Unexpected death/ suicide of a colleague | 5.03 (36) |

| Aggressive behavior of patients or relatives | 37.43 (268) |

| Other | 5.17 (37) |

Table 3.

(Occupational) Groups which those affected by SVP sought out for help (selection of multiple sources possible). N=372.

Table 3.

(Occupational) Groups which those affected by SVP sought out for help (selection of multiple sources possible). N=372.

| (Occupational) Group | Percentage of Participants (n) |

|---|---|

| Colleagues | 92.47 (344) |

| Supervisors | 38.44 (143) |

| Management | 5.38 (20) |

| Family/ Friends | 34.68 (129) |

| Counsellors/Psychotherapists/Psychologic Counselling | 16.13 (60) |

Table 4.

Frequencies of severeness of different symptoms experienced after SV event. N=662.

| Symptom | Not at all | Weakly pronounced | Strongly pronounced | I don’t know |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fear of exclusion by colleagues | 407 (61.48%) | 145 (21.90%) | 90 (13.6%) | 20 (3.02%) |

| Fear of losing the job | 475 (71.75%) | 108 (16.31%) | 64 (9.67%) | 15 (2.27%) |

| Listlessness | 265 (40.03%) | 258 (38.97%) | 124 (18.73%) | 15 (2.27%) |

| Depressive mood | 195 (29.46%) | 314 (47.43%) | 140 (21.15%) | 13 (1.96%) |

| Concentration difficulties | 198 (29.91%) | 304 (45.92%) | 144 (21.75%) | 16 (2.42%) |

| Reliving the situation outside of professional life | 271 (40.94%) | 220 (33.23%) | 142 (21.45%) | 29 (4.38%) |

| Reliving the situation in similar professional situations | 127 (19.18%) | 290 (43.81%) | 227 (34.29%) | 18 (2.72%) |

| Aggressive, risky behavior | 510 (77.04%) | 94 (14.20%) | 29 (4.38%) | 29 (4.38%) |

| Defensive, overly cautious behavior | 220 (33.23%) | 267 (40.33%) | 160 (24.17%) | 15 (2.27%) |

| Psychosomatic reactions (head- or backaches) | 195 (29.46%) | 204 (30.82%) | 225 (33.99%) | 38 (5.74%) |

| Insomnia or excessive need for sleep | 119 (17.98%) | 234 (35.35%) | 298 (45.02%) | 11 (1.66%) |

| Use of alcohol/drugs because of event | 490 (74.02%) | 135 (20.39%) | 26 (3.93%) | 11 (1.66%) |

| Feelings of shame | 408 (61.63%) | 154 (23.26%) | 85 (12.84%) | 15 (2.27%) |

| Feelings of guilt | 260 (39.27%) | 235 (35.50%) | 153 (23.11%) | 14 (2.11%) |

| Self-doubts | 180 (27.19%) | 271 (40.94%) | 202 (30.51%) | 9 (1.36%) |

| Social isolation | 433 (65.41%) | 152 (22.96%) | 67 (10.12%) | 10 (1.51%) |

| Anger towards others | 254 (38.37%) | 220 (33.23%) | 178 (26.89%) | 10 (1.51%) |

| Anger towards myself | 365 (55.14%) | 180 (27.19%) | 103 (15.56%) | 14 (2.11%) |

| Desire for support from others | 125 (18.88%) | 251 (37.92%) | 261 (39.43%) | 25 (3.78%) |

| Desire to process the event for better understanding | 109 (16.47%) | 221 (33.38%) | 306 (46.22%) | 26 (3.93%) |

Table 5.

Differences in the rating of potential support measures following an adverse event between participants who reported prior experience with SVP and those who reported no such experience in their careers. N=775.

Table 5.

Differences in the rating of potential support measures following an adverse event between participants who reported prior experience with SVP and those who reported no such experience in their careers. N=775.

| Support Measure | M | SD | M1 | SD1 | M2 | SD2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| all participants | SVs | Non-SVs | |||||

| The possibility to take time off from work directly to process the event | 1.70 | 0.85 | 1.72 | 0.86 | 1.63 | 0.82 | 0.93 |

| Access to professional counseling or psychological/psychiatric consultations (crisis intervention) | 1.64 | 0.96 | 1.65 | 0.96 | 1.58 | 0.97 | <0.01 |

| The possibility to discuss my emotional/ethical thoughts | 1.57 | 0.87 | 1.53 | 0.84 | 1.75 | 0.98 | <0.01 |

| Clear and timely information regarding the course of action after a serious event (e.g., damage analysis, error report) | 1.55 | 0.87 | 1.54 | 0.86 | 1.59 | 0.90 | 0.02 |

| Formal emotional support in the sense of organized collegial help | 1.65 | 0.92 | 1.62 | 0.91 | 1.79 | 0.98 | 0.01 |

| Informal emotional support | 1.75 | 0.98 | 1.75 | 1.00 | 1.79 | 0.89 | 0.01 |

| Quick processing of the situation/quick crisis intervention (in a team or individually) | 1.43 | 0.81 | 1.41 | 0.78 | 1.53 | 0.91 | 0.01 |

| Support/Mentoring when continuing to work with patients | 2.01 | 1.05 | 1.99 | 1.04 | 2.10 | 1.11 | 0.6 |

| Support when communicating with patients and/or relatives | 1.97 | 1.06 | 1.97 | 1.04 | 1.99 | 1.13 | 0.5 |

| Guidelines regarding the role/activities expected of me during a serious event | 1.94 | 1.05 | 1.91 | 1.04 | 2.06 | 1.09 | 0.46 |

| Support to be able to take an active role in the processing of the event | 1.67 | 0.89 | 1.66 | 0.90 | 1.71 | 0.87 | 0.02 |

| A secure possibility to give information on how to prevent similar events in the future | 1.58 | 0.90 | 1.55 | 0.87 | 1.72 | 1.01 | 0.04 |

| The possibility to access legal consultation after a severe event | 1.70 | 0.85 | 1.72 | 0.86 | 1.63 | 0.82 | 0.01 |

SV: Second Victim, M und SD: Mean and standard deviation of the participants who completed the survey (n=353) regardless of the SV Status, M1 and SD1: Mean and standard deviation of the participants who reported that they have already experienced SVP, M2 and SD2: the group of participants who reported that they have not experienced SVP in their career, p: a p-Value of The Mann-Whitney U-test comparing the rating of the support measure between the group of participants who reported that they have already experienced SVP and the group of participants that reported that they have not experienced SVP in their career, support measures were scored on a five-point descending Likert scale ranging from one “very helpful” to five “not helpful at all” (“not helpful at all” =4, “rather to very helpful” = 1).

Table 6.

Factors Associated with the Likelihood of Becoming a SV. Results of binary-logistic regression. N=763.

Table 6.

Factors Associated with the Likelihood of Becoming a SV. Results of binary-logistic regression. N=763.

| Predictor | Regression Coefficient B with BCa 95% CI |

p | Odds Ratio Exp(B)1 | Odds Ratio 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Gender2 | -0.53 [-0.99, -0.13] | 0.03 | 0.59 | 0.38 | 0.91 |

| Age | -0.01 [-0.40,0.03] | 0.64 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 1.03 |

| Professional experience (years) | 0.01[-0.25, 1.22] | 0.59 | 1.01 | 0.98 | 1.04 |

| Education3 | 0.49 [-0.25, 0.65] | 0.13 | 1.62 | 0.83 | 3.16 |

| Full-time or part-time job4 | 0.20 [-0.33, 0.70] | 0.31 | 1.22 | 0.81 | 1.83 |

| Leadership5 | 0.17 [-0.40, 0.47] | 0.61 | 1.19 | 0.65 | 2.18 |

| Workplace6 | 0.02 [-0.12, 0.41] | 0.93 | 1.02 | 0.69 | 1.52 |

| Openness | 0.16 [-0.18, 0.54] | 0.20 | 1.17 | 0.90 | 1.52 |

| Conscientiousness | 0.14 [-0.51, 0.16] | 0.38 | 1.16 | 0.83 | 1.61 |

| Extraversion | -0.20 [-0.05, 0.42] | 0.25 | 0.82 | 0.59 | 1.13 |

| Agreeableness | -0.19 [-0.46, 0.15] | 0.27 | 1.18 | 0.92 | 1.52 |

| Neuroticism | 1.16 [-0.52, 3.18] | 0.17 | 0.83 | 0.61 | 1.12 |

Outcome is experienced SV status (dichotomous yes 1 vs. no 0), 1Exponentiation of the B Coefficient, 2referent category is male, 3referent category bachelor, master, PhD, diploma, 4referent category is part time job, 5referent category is having a leadership role, 6referent category is acute care, intensive station unit or operation theatre, BCa 95%CI: Bias-corrected and accelerated boot-strapping 95% confidence intervals based on 5,000 bootstrap samples. Please note that we excluded three individuals from the analysis due to their diverse gender identities (i.e., not male, female, or non-binary) and their small number within this category. This exclusion was made to maintain the integrity and clarity of the analysis.

Table 7.

Demographic, workplace-related and personality trait factors Associated with the Symptom Load after the SV Experience. Results of multiple linear regression, n=763, (R2= 0.04); F(12, 450)=1.75, p=0.05.

Table 7.

Demographic, workplace-related and personality trait factors Associated with the Symptom Load after the SV Experience. Results of multiple linear regression, n=763, (R2= 0.04); F(12, 450)=1.75, p=0.05.

| Predictor | Unstandardized Regression Coefficient B | p | BCa 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Gender1 | -0.91 | 0.03 | -1.68 | -0.07 |

| Age | -0.02 | 0.48 | -0.08 | 0.04 |

| Professional experience (years) | 0.01 | 0.40 | -0.05 | 0.06 |

| Education2 | 0.41 | 0.62 | -0.78 | 1.67 |

| Full-time or part-time job3 | 0.28 | 0.61 | -0.36 | 0.92 |

| Management role4 | 0.23 | 0.12 | -0.60 | 1.20 |

| Workplace5 | -0.17 | 0.90 | -0.75 | 0.45 |

| Openness | 0.31 | 0.73 | -0.07 | 0.71 |

| Conscientiousness | 0.03 | 0.93 | -0.46 | 0.59 |

| Extraversion | 0.11 | 0.82 | -0.54 | 0.74 |

| Agreeableness | 0.49 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.90 |

| Neuroticism | 0.06 | 0.48 | -0.39 | 0.52 |

Outcome is sum and severity of suffered symptoms after a SV experience, 1referent category is male, 2referent category bachelor, master, PhD, diploma, 3referent category is part time job, 4referent category is having a leadership role, 5referent category is acute care, intensive station unit or operation theatre, Lower BCa 95%CI and Upper BCa 95%CI: lower and upper limits of 95% bias-corrected and accelerated bootstrapped confidence interval of unstandardized regression coefficient B based on 5,000 bootstrap samples. Please note that we excluded three individuals from the analysis due to their diverse gender identities (i.e., not male, female, or non-binary) and their small number within this category. This exclusion was made to maintain the integrity and clarity of the analysis.

Table 8.

Demographic, workplace-related, and personality trait factors, along with the type of adverse event associated with the Symptom Load after the SV experience. Results of multiple linear regression analysis are presented, n=763, R2=0.16, F(16,746)=8.94, p<0.001.

Table 8.

Demographic, workplace-related, and personality trait factors, along with the type of adverse event associated with the Symptom Load after the SV experience. Results of multiple linear regression analysis are presented, n=763, R2=0.16, F(16,746)=8.94, p<0.001.

| Predictor | Unstandardized Regression Coefficient B | p | BCa 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Gender1 | 0.46 | 0.21 | -1.19 | 0.29 |

| Age | 0.02 | 0.54 | -0.07 | 0.04 |

| Professional experience (years) | 0.004 | 0.86 | -0.04 | 0.05 |

| Education2 | 0.26 | 0.60 | -0.67 | 1.18 |

| Full-time or part-time job3 | 0.26 | 0.40 | -0.35 | 0.83 |

| Management role4 | 0.05 | 0.91 | -0.91 | 0.82 |

| Workplace5 | 0.10 | 0.75 | -0.74 | 0.46 |

| Openness | 0.18 | 0.30 | -0.17 | 0.55 |

| Conscientiousness | 0.08 | 0.76 | -0.35 | 0.55 |

| Extraversion | 0.19 | 0.47 | -0.33 | 0.68 |

| Agreeableness | 0.47 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.87 |

| Neuroticism | 0.31 | 0.17 | -0.14 | 0.78 |

| Incident with patient harm6 | 4.49 | <0.001 | 3.65 | 5.40 |

| Unexpected death/ suicide of a patient6 | 3.12 | <0.001 | 2.33 | 3.92 |

| Unexpected death/ suicide of a colleague6 | 2.39 | <0.001 | 1.10 | 3.75 |

| Aggressive behavior of patients or relatives6 | 3.31 | <0.001 | 2.60 | 3.99 |

Outcome is sum and severity of suffered symptoms after a SV experience, 1referent category is male, 2referent category bachelor, master, PhD, diploma, 3referent category is part time job, 4referent category is having a leadership role, 5referent category is acute care, intensive station unit or operation theatre, 6referent category is incident without a patient harm, lower BCa 95%CI and Upper BCa 95%CI: lower and upper limits of 95% bias-corrected and accelerated bootstrapped confidence interval of unstandardized regression coefficient B based on 5,000 bootstrap samples. Please note that we excluded three individuals from the analysis due to their diverse gender identities (i.e., not male, female, or non-binary) and their small number within this category. This exclusion was made to maintain the integrity and clarity of the analysis.

Table 9.

Unstandardized indirect effects of length of professional experience as a nurse in years on symptom load caused by SV experience via Big Five personality traits.

Table 9.

Unstandardized indirect effects of length of professional experience as a nurse in years on symptom load caused by SV experience via Big Five personality traits.

| Unstandardized Effect | BootLLCI | BootULCI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total unstandardizied indirect effect | -0.004 | -0.001 | 0.002 |

| Openness | -0.001 | -0.004 | 0.0004 |

| Conscientiousness | -0.0001 | -0.003 | 0.002 |

| Extraversion | -0.001 | -0.003 | 0.002 |

| Agreeableness | -0.002 | -0.005 | 0.001 |

| Neuroticism | -0.0004 | -0.005 | 0.004 |

BootLLCI, BootULCI: lower and upper limits of 95% confidence interval based on 5,000 deviation correction bootstrapped samples.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Copyright: This open access article is published under a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license, which permit the free download, distribution, and reuse, provided that the author and preprint are cited in any reuse.

Nurses’ Silence: Understanding the Impacts of Second Victim Phenomenon Among Israeli Nurses

Rinat Cohen

et al.

,

2023

Moral Resilience Reduces Levels of Quiet Quitting, Job Burnout, and Turnover Intention among Nurses: Evidence in the Post COVID-19 Era

Petros Galanis

et al.

,

2023

Impact of Workplace Bullying on Quiet Quitting in Nurses: The Mediating Effect of Coping Strategies

Petros Galanis

et al.

,

2024

MDPI Initiatives

Important Links

© 2024 MDPI (Basel, Switzerland) unless otherwise stated