Bacterial fossils exhibit earliest hints of photosynthesis

Oxygen emitted by these structures likely paved the way for plants and animals to evolve

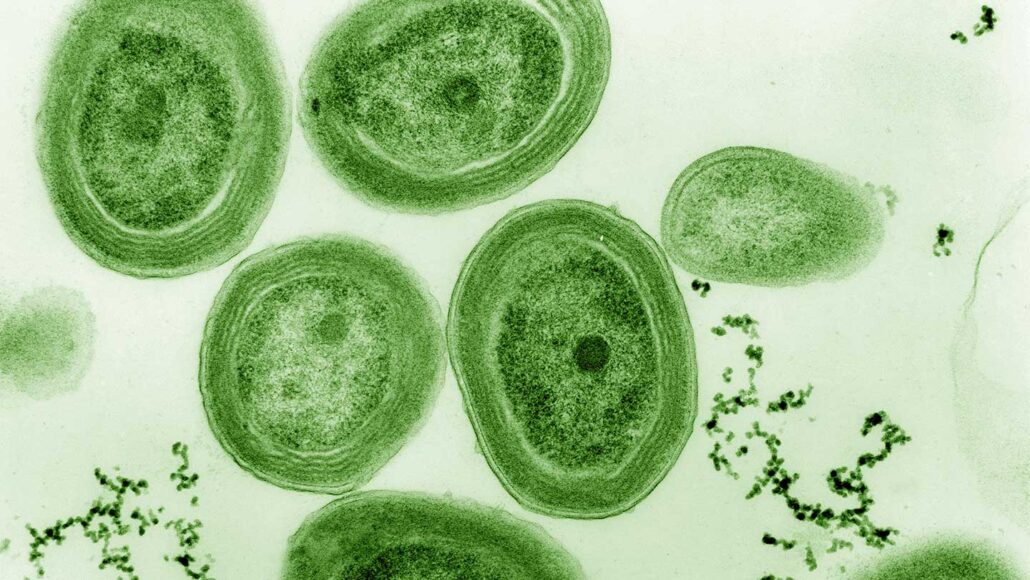

Cyanobacteria “invented” photosynthesis billions of years ago. Today, these Prochlorococcus live in the ocean. Fossils from 1.78 billion years ago now reveal evidence of the structures that some ancient bacteria used to turn sunlight into food. They would also give off oxygen.

Luke Thompson/Chisholm Lab, Nikki Watson/Whitehead/MIT

Ancient tiny fossils may hold early signs of a power that shaped the world. That power: photosynthesis. It released oxygen to help shape our atmosphere.

Cyanobacteria are one of Earth’s oldest known life forms. They “invented” photosynthesis billions of years ago. The new fossils, found in Australia, are from cyanobacteria.

Like plants, these microbes make their own food through photosynthesis. In the process, they release oxygen as a waste. In most modern cyanobacteria (and plants), photosynthesis takes place inside special structures. They’re called thylakoid (THY-luh-koyd) membranes. And the newfound fossil bacteria are chock-full of structures that look a lot like today’s thylakoids.

Researchers at the University of Liège, in Belgium, shared their new findings January 18 in Nature.

These fossils date from 1.73 billion to 1.78 billion years ago. That makes them the oldest thylakoids ever found, by far. They existed 1.2 billion years earlier than previous fossil evidence had suggested.

Before that, our air had only whiffs of oxygen, here and there. But after millions of years of photosynthesis, Earth’s oxygen levels skyrocketed. Scientists call this the Great Oxidation Event. It took place some 2.4 billion years ago.

These bacteria transformed Earth’s atmosphere. “So they’re a big deal,” says Woodward Fischer. The oxygen they released allowed more complex life to evolve, such as plants and animals. Fischer studies the geology and biology of the early Earth. He works at the California Institute of Technology, in Pasadena, and did not take part in the new study.

The discovery of these fossils is surprising, in a good way, Fischer says. “This is the kind of information that I thought we were not going to be able to pull out of fossils.”

Most fossils preserve hard tissues, such as bone or shells. Bacteria don’t contain such hard bits. These fossils are “just compressions of carbon,” he notes, squished into mud.

So finding preserved bacteria is impressive. But even more amazing is what these fossils reveal.

Complex structures can be seen inside the microbes. These details could reveal even more about the biology of ancient life, Fischer says.

Rare remains

Exactly when thylakoids evolved is hotly debated. Before this study, researchers had to rely on indirect evidence. Their clues came from genetics and chemical studies.

There were some hints that thylakoids existed by the time these fossils formed, says Patricia Sanchez-Baracaldo. She works at the University of Bristol in England. There, she studies how bacteria and other tiny life forms have changed over millions or even billions of years.

It’s exciting to see fossil evidence of such old thylakoids, she says. Any evidence from so far back “is important,” she notes, “because the fossil record is really very sparse.”

Many rocks that might harbor such fossils have been compressed and “cooked.” This pressure can destroy a cell’s delicate structures. That includes thylakoids, notes study author Emmanuelle Javaux. “We didn’t know that they could be preserved in such old microfossils,” this astrobiologist says.

But she has no doubt about what her team spotted. The dark lines stacked through tiny sausage-shaped cells represent thylakoids, she says. “It cannot be something else,” she argues. “This arrangement is very unique to cyanobacteria with thylakoids.”

Her team looked at microfossils from around the world. The oldest thylakoids were found in shale from Australia. The team also found the structures in fossils from Canada. Those were about 1 billion years old.

Educators and Parents, Sign Up for The Cheat Sheet

Weekly updates to help you use Science News Explores in the learning environment

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

Similarly aged fossils from Congo lack thylakoids. The rocks had reached slightly hotter temperatures than the others. This might have destroyed evidence for any thylakoids. Or maybe the Congo fossils are cyanobacteria that never evolved the structures. They might be a whole different type of microbe.

Some researchers think thylakoids evolved even longer ago — before the Great Oxidation Event. Stacks of thylakoids could have helped the bacteria make a lot more oxygen.

By the time these now-fossilized bacteria lived, the Earth’s atmosphere had changed again. Oxygen levels had plummeted. There was much less oxygen in the air than we have today, Sanchez-Baracaldo says. But those fossils hint that there may have been small pockets where oxygen was abundant. This could have helped early forms of plants and animals evolve.

Javaux’s team hopes to study really old rocks — from before the Great Oxidation Event. They’re on the hunt for even more ancient evidence of thylakoids.