- India from the Paleolithic Period to the decline of the Indus civilization

- The development of Indian civilization from c. 1500 bce to c. 1200 ce

- The early Muslim period

- The Mughal Empire, 1526–1761

- The reign of Akbar the Great

- India and European expansion, c. 1500–1858

- British imperial power, 1858–1947

News •

The dominion of India was reborn on January 26, 1950, as a sovereign democratic republic and a union of states. That day is celebrated annually as Republic Day, a national holiday commemorating the adoption of India’s constitution on January 26, 1950. With universal adult franchise, India’s electorate was the world’s largest, but the traditional feudal roots of most of its illiterate populace were deep, just as their religious caste beliefs were to remain far more powerful than more recent exotic ideas, such as secular statehood. Elections were to be held, however, at least every five years, and the major model of government followed by India’s constitution was that of British parliamentary rule, with a lower House of the People (Lok Sabha), in which an elected prime minister and a cabinet sat, and an upper Council of States (Rajya Sabha). Nehru led his ruling Congress Party from New Delhi’s Lok Sabha until his death in 1964. The nominal head of India’s republic, however, was a president, who was indirectly elected. India’s first two presidents were Hindu Brahmans, Rajendra Prasad and Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, the latter a distinguished Sanskrit scholar who had lectured at the University of Oxford. Presidential powers were mostly ceremonial, except for brief periods of “emergency” rule, when the nation’s security was believed to be in great danger and normal constitutional procedures and civil rights were feared to be too cumbersome or threatening.

India’s federation divided powers between the central government in New Delhi and a number of state governments (crafted from former British provinces and princely states), each of which also had a nominal governor at its head and an elected chief minister with a cabinet to rule its legislative assembly. One of the Congress Party’s long-standing resolutions had called for the reorganization of British provincial borders into linguistic states, where each of India’s major regional languages would find its administrative reflection, while English and Hindi would remain joint national languages for purposes of legislation, law, and service examinations. Pressure for such reorganization increased in 1953, after the former British province of Madras was divided into Tamil Nadu (“Land of the Tamils”) and Andhra (from 1956 Andhra Pradesh), where Telugu, another Dravidian tongue, was spoken by the vast majority. (Andhra Pradesh itself was divided in 2014, with the northern, Telugu-speaking portion being split off to become the new state of Telangana. Hyderabad [in Telangana] served as the capital of each state.) Nehru thus appointed the States Reorganisation Commission to redesign India’s internal map, which led to a major redrawing of administrative boundaries, especially in southern India, by the States Reorganization Act, passed in 1956. Four years later, in 1960, the enlarged state of Bombay was divided into Marathi-speaking Maharashtra and Gujarati-speaking Gujarat. Despite those changes, the difficult process of reorganization continued and demanded attention in many regions of the subcontinent, whose truly “continental” character was perhaps best seen in this ongoing linguistic agitation. Among the most difficult problems was a demand by Sikhs that their language, Punjabi, with its sacred Gurmukhi script, be made the official tongue of Punjab, but in that state many Hindus, fearing that they would find themselves disadvantaged, insisted that as Hindi speakers they too deserved a state of their own, if indeed the Sikhs were to be granted the Punjabi suba (state) for which so many Sikhs agitated. Nehru, however, refused to agree to a separate Sikh state, as he feared that such a concession to the Sikhs, who were both a religious and a linguistic group, might open the door to further “Pakistan-style” fragmentation.

Foreign policy

Nehru served as his own foreign minister and throughout his life remained the chief architect of India’s foreign policy. The dark cloud of partition, however, hovered for years in the aftermath of India’s independence, and India and Pakistan were left suspicious of one another’s incitements to border violence.

The princely state of Jammu and Kashmir triggered the first undeclared war with Pakistan, which began a little more than two months after independence. Prior to partition, princes were given the option of joining the new dominion of India within which their territory lay, and, thanks to the vigorous lobbying of Mountbatten and Patel, most of the princes agreed to do so, accepting handsome pensions (so-called “privy purses”) as rewards for relinquishing sovereignty. Of some 570 princes, only 3 had not acceded to the new dominion or gone immediately over to Pakistan—those of Junagadh, Hyderabad, and Kashmir. The nawab of Junagadh and the nizam of Hyderabad were both Muslims, though most of their subjects were Hindus, and both states were surrounded, on land, by India. Junagadh, however, faced Pakistan on the Arabian Sea, and when its nawab followed Jinnah’s lead in opting to join that Muslim nation, India’s army moved in and took control of the territory. The nizam of Hyderabad was more cautious, hoping for independence for his vast domain in the heart of southern India, but India refused to give him much more than one year and sent troops into the state in September 1948. Both invasions met little, if any, resistance, and both states were swiftly integrated into India’s union.

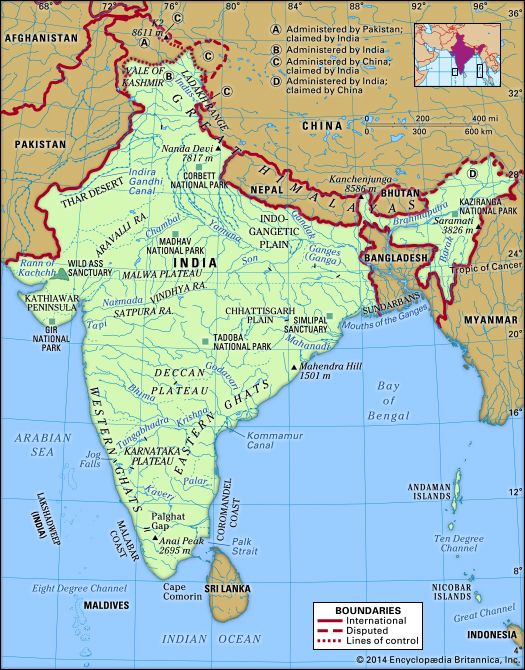

Kashmir, lying in the Himalayas, presented a different problem. Its maharaja was Hindu, but about three-fourths of its population was Muslim, and the region itself was contiguous to both new dominions, sitting like a crown atop South Asia. Maharaja Hari Singh tried at first to remain independent, but in October 1947 Pashtun (Pathan) tribesmen from the North-West Frontier of Pakistan invaded Kashmir in trucks, heading toward Srinagar. The invasion triggered India’s first undeclared war with Pakistan and led at once to the maharaja’s decision to opt for accession to India. Mountbatten and Nehru airlifted Indian troops into Srinagar, and the tribesmen were forced to fall back to a line that has, since early 1949, partitioned Kashmir into Pakistan-administered Azad Kashmir (the western portion of Kashmir) and Gilgit-Baltistan (the northern portion of Kashmir, also administered by Pakistan; formerly “Northern Areas”) and India-administered Jammu and Kashmir (the southern portion of Kashmir) and Ladakh (the eastern portion of Kashmir; administered as part of Jammu and Kashmir until 2019). Nehru initially agreed to Mountbatten’s proposal that a plebiscite be held in the entire state as soon as hostilities ceased, and a UN-sponsored cease-fire was agreed to by both parties on January 1, 1949. No statewide plebiscite was held, however, for in 1954, after Pakistan began to receive arms from the United States, Nehru withdrew his support.

India’s foreign policy, defined by Nehru as nonaligned, was based on Five Principles (Panch Shila): mutual respect for other nations’ territorial integrity and sovereignty; nonaggression; noninterference in internal affairs; equality and mutual benefit; and peaceful coexistence. These principles were, ironically, articulated in a treaty with China over the Tibet region in 1954, when Nehru still hoped for Sino-Indian “brotherhood” and leadership of a “Third World” of nonviolent nations, recently independent of colonial rule, eager to save the world from Cold War superpower confrontation and nuclear annihilation.

China and India, however, had not resolved a dispute over several areas of their border, most notably the section demarcating a barren plateau in Ladakh—most of which was called Aksai Chin, which was claimed by India as part of Jammu and Kashmir state but never properly surveyed—and the section bordered on the north by the McMahon Line, which stretched from Bhutan to Burma (Myanmar) and extended to the crest of the Great Himalayas. The latter area, designated as the North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA) in 1954, was claimed on the basis of a 1914 agreement between Arthur Henry McMahon, the British foreign secretary for India, and Tibetan officials but was never accepted by China. After China had reasserted its authority over Tibet in 1950, it began appealing to India—but to no avail—for negotiations over the border. This Sino-Indian dispute was exacerbated in the late 1950s after India discovered a road across Aksai Chin built by the Chinese to link its autonomous region of Xinjiang with Tibet. The tension was further heightened when in 1959 India granted asylum to the Dalai Lama, Tibet’s spiritual leader. Full-scale war (the month-long Sino-Indian War) blazed in October 1962 when a Chinese army moved easily through India’s northern outposts and advanced virtually unopposed toward the plains of Assam before Beijing ordered their unilateral withdrawal.

The war was a blow to Nehru’s most-cherished principles and ideals, though India soon secured its northern defenses as a result of swift and extensive American and British military support, including the dispatch of U.S. bombers to the world’s highest border. India’s “police action” of integrating Portuguese Goa into the union by force in 1961 represented another fall from the high ground of nonviolence in foreign affairs, which Nehru so often claimed for India in his speeches to the UN and elsewhere. During his premiership, Nehru tried hard to identify the country’s foreign policy with anti-colonialism and anti-racism. He also tried to promote India’s role as the peacemaker, which was seen as an extension of the policies of Gandhi and as deeply rooted in the indigenous religious traditions of Buddhism, Jainism, and Hinduism. Like most foreign policies, India’s was, in fact, based first of all on its government’s perceptions of national interest and on security considerations.

Economic planning and development

As a Fabian socialist, Nehru had great faith in economic planning and personally chaired his government’s Planning Commission. India’s First Five-Year Plan was launched in 1951, and most of its funds were spent on rebuilding war-shattered railroads and on irrigation schemes and canals. Food grain production increased from 51 million tons in 1951 to 82 million tons by the end of the Second Five-Year Plan (1956–61). During that same decade, however, India’s population grew from about 360 million to 440 million, which eliminated real economic benefits for all but large landowners and the wealthiest and best-educated quarter of India’s urban population. The landless and unemployed lower half of India’s fast-growing population remained inadequately fed, ill-housed, and illiterate. Nehru’s wisdom in keeping his country nonaligned helped accelerate India’s economic development, as India received substantial aid from both sides of the Cold War, with the Soviet Union and eastern Europe contributing almost as much in capital goods and technical assistance as did the United States, Great Britain, and what was then West Germany. The growth of iron and steel industries soon became a truly international example of coexistence, with the United States building one plant, the Soviet Union another, Britain a third, and West Germany a fourth. For the Third Five-Year Plan (1961–66), launched during Nehru’s era, an Aid India Consortium of the major Western powers and Japan provided some $5 billion in capital and credits, and, as a result, India’s annual iron output rose to nearly 25 million tons by the plan’s end, with about three times that amount of coal produced and almost 40 billion kilowatt-hours of electric power generated. India had become the world’s 10th most advanced industrial country in terms of absolute value of output, though it remained per capita one of the least productive of the world’s major countries.

As modernity brought added comforts and pleasure to India’s urban elite, the gap between the larger industrial urban centers and the areas of extensive rural poverty became greater. Various programs designed to reduce rural poverty were tried, many ostensibly in emulation of Gandhi’s sarvodaya (rural “uplift”) philosophy, which advocated community sharing of all resources for the people’s mutual benefit and enhancement of peasant life. The social reformer Vinoba Bhave started a bhoodan (“gift of land”) movement, in which he walked from village to village and asked large landowners to “adopt” him as their son and to give him a portion of their property, which he would then distribute among the landless. He later expanded that program to include gramdan (“gift of village”), in which villagers voluntarily surrendered their land to a cooperative system, and jivandan (“gift of life”), the giving of all one’s labour, the latter attracting volunteers as famous as the socialist J.P. (Jaya Prakash) Narayan, who was the inspiration for the foundation of the Janata (People’s) Party opposition coalition to the Congress Party in the mid-1970s. The Ford Foundation, an American philanthropic organization, began a community development and rural extension program in the early 1950s that encouraged young Indian college students and technical experts to focus their skills and knowledge on village problems. India’s half million villages, however, were slow to change, and, though a number of showcase villages emerged in the environs of New Delhi, Bombay (later renamed Mumbai), and other large cities, the more-remote villages remained centers of poverty, caste division, and illiteracy.

It was not until the late 1960s that chemical fertilizers and high-yield food seeds brought the Green Revolution in agriculture to India. The results were mixed, as many poor or small farmers were unable to afford the seeds or the risks involved in the new technology. Moreover, as production of rice and, especially, wheat increased, there was a corresponding decrease in other grain production. Farmers who benefited most were from the major wheat-growing areas of Haryana, Punjab, and western Uttar Pradesh.

Post-Nehru politics and foreign policy

At his death on May 27, 1964, Nehru’s only child and closest confidante, Indira Gandhi, was with him. Long separated from her husband—Feroze Gandhi, by then deceased—Indira had moved into Teen Murti Bhavan, the prime minister’s mansion, with her two sons, Rajiv and Sanjay. She had accompanied her father the world over and had been the leader of his Congress Party’s “ginger group” youth movement, as well as Congress president, but, as a young mother and widow, she had not as yet served in parliament nor in her father’s cabinet and, hence, did not put herself forward as a candidate for prime minister. Though it appeared that Nehru had been grooming her as his successor, he had denied any such intention, and his party instead chose Lal Bahadur Shastri as India’s second prime minister. Shastri had devoted his life to party affairs and had served Nehru well both inside and outside his cabinet. His modesty and simplicity, moreover, appealed to most Indians.

The 1965 war with Pakistan

Almost immediately after Shastri took office, India was faced with a threat of war from Pakistan. Pakistan’s president, Mohammad Ayub Khan, had led a military coup in 1958 that put him in charge of his country’s civil and military affairs, and his regime had received substantial military support from the United States. By 1965 Ayub felt ready to test India’s frontier outposts, first in Sindh (Sind) and then in Kashmir. The first skirmishes were fought in the Rann of Kachchh (Kutch) in April, and Pakistan’s U.S.-made tanks rolled to what seemed like an easy victory over India’s counterparts. The Commonwealth prime ministers and the UN quickly prevailed on both sides to agree to a cease-fire and withdrawal of forces to the prewar borders. Pakistan, however, believed it had won and that India’s army was weak, and Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, Ayub’s foreign minister, urged another round in Kashmir that summer, to which Ayub agreed. In mid-August Pakistan launched “Operation Grandslam” with the hope of cutting across the only significant overland route to Kashmir before India could bring up its outmoded tanks. India’s forces, however, moved a three-pronged tank attack aimed at Lahore and Sialkot across the international border in Punjab early in September. The great city of Lahore was in range of Indian tank fire by September 23, when both sides agreed on a UN cease-fire. Each country’s army had suffered considerable losses and had run low on ammunition as a result of the immediate decision by the United Kingdom and the United States to embargo all further military shipments to both armies. Shastri was hailed as a hero in New Delhi.

A Soviet-sponsored South Asian peace conference was held early in January 1966 at Tashkent, in what was then the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic, where Ayub and Shastri finally reached an agreement on January 10 to “restore normal and peaceful relations” between India and Pakistan. The next morning, however, Shastri was dead of a heart attack, and the Tashkent Agreement hardly outlived him. Before the month’s end, Indira Gandhi, who had served in Shastri’s cabinet as minister of information and broadcasting, had been elected by the Congress Party to become India’s next prime minister. She easily defeated her only rival, Morarji Desai.